Last updated: April 4, 2023

Article

Incarcerated Japanese Americans at Death Valley

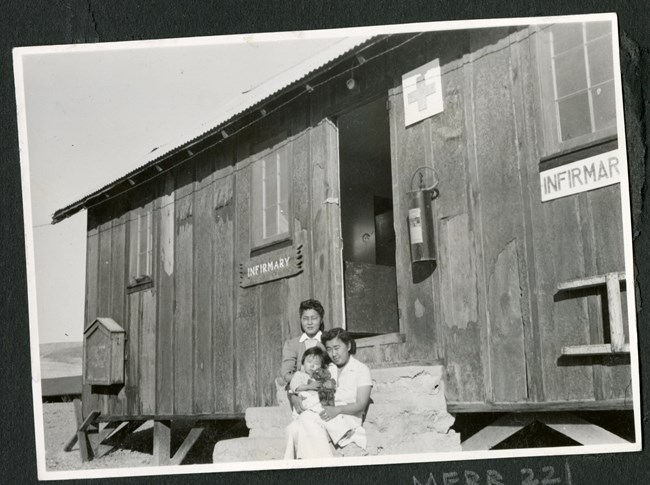

Courtesy Eastern California Museum, Merritt Photo Collection.

On February 19, 1942 – 81 years ago today – President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which provided for the removal of “any and all people” from designated military zones. The US Army, under direction of Lt. Gen. John L. DeWitt, used this order to forcibly remove over 110,000 Japanese Americans from the West Coast of the United States and incarcerate them in inland camps. More than forty years later, the US government under President Ronald Reagan formally apologized for this unconstitutional mass incarceration of US citizens and resident immigrants, acknowledging its causes as “war hysteria, race prejudice, and a failure of political leadership.”

A lesser-known part of Japanese American history took place right here in Death Valley National Park where the government moved 60 people from the incarceration camp at Manzanar – about 100 miles west – into the abandoned Civilian Conservation Crew (CCC) camp at Cow Creek. Identified by the government as people whose well-being was threatened following a revolt in Manzanar on December 6, 1942 – during which military police opened fire on an unarmed crowd, killing two young men – Japanese Americans at Cow Creek ranged in age from babies to grandparents.

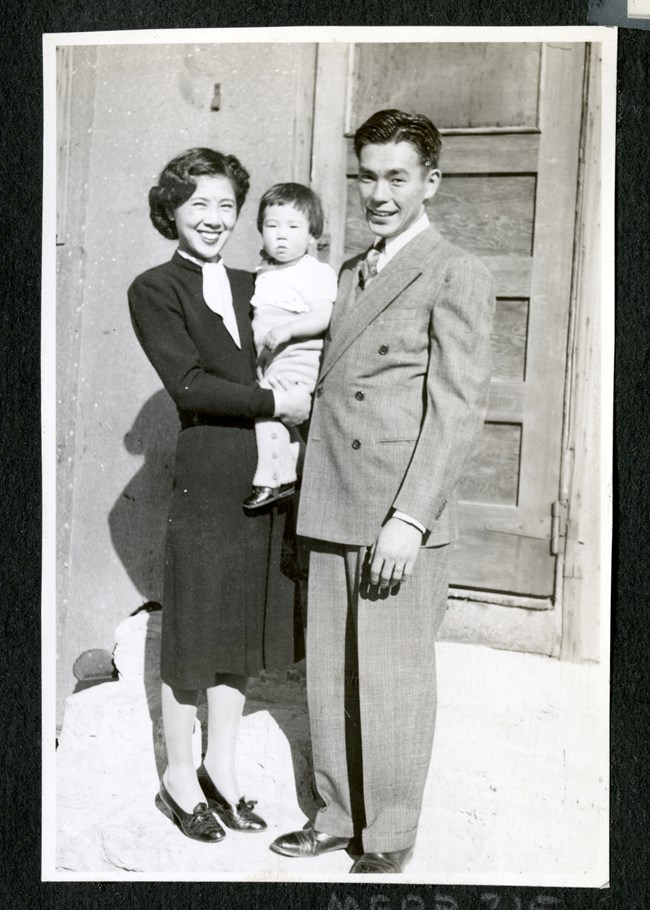

Courtesy Eastern California Museum, Merritt Photo Collection.

Welcomed by Park Superintendent T.R. Goodwin, along with park rangers and their families, incarcerated Japanese Americans in Death Valley passed the time by helping out the wartime skeleton staff with maintenance projects in the park, taking on any and all tasks, from painting new signs to cleaning the park headquarters’ water supply. In a January 20, 1943 letter, Togo Tanaka wrote, “Here at Death Valley, where I have been digging ditches, cleaning springs, hauling rocks and having one wonderful time with the Park Rangers, my clogged system has been cleared mentally and physically. We’ve shaken the atmosphere of Manzanar completely.” After two months in Death Valley, Tanaka and his family were resettled by the government to Chicago, Illinois.

Reflecting in 1973 on his incarceration in Cow Creek, Tadaichi Uyeno wrote, “We cursed the people who clamored to put us into concentration camps. We knew all Americans did not sanction the deprivation of our rights… In this vast country of ours, we were sure there were people who didn’t hate us, who sympathized with our plight and would try to help us in their own particular way. We didn’t know we would find them in the desert next to our camp… These rangers and their families lit the candles for us to penetrate the darkness of gloom and despair which we had faced."

To learn more about Manzanar and the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II, visit: www.nps.gov/manz.

Click here to learn more about the Manzanar revolt, historically called the Manzanar “riot.” or visit the Confinement and Ethnicity page.

Photos courtesy Eastern California Museum, Merritt Photo Collection. Click to view the full collection, along with thousands more archival resources.

Courtesy Eastern California Museum, Merritt Photo Collection.

Tags

- death valley national park

- manzanar national historic site

- death valley national park

- death valley

- manzanar

- manzanar national historic site

- manzanar war relocation center

- cow creek

- world war ii

- japanese american incarceration

- japanese american

- japanese american internment

- aanhpi heritage month

- aanhpi heritage

- asian american

- asian american heritage

- asian american heritage month