Part of a series of articles titled Travel El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro National Historic Trail: Essays .

Article

History and Significance of El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro

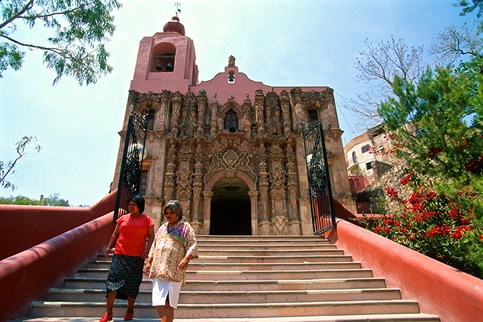

among the many churches constructed in Mexico during the Spanish silver

rush that led to the establishment of El Camino Real. Photo © Jack Parsons

Traditionally, the telling of the history of the United States moved from east to west, cast in a timeline of the notable people, places and events that shaped the country from the 1607 founding of Jamestown, Virginia, to today. With the designation of El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro as a National Historic Trail on September 13, 2000, the U.S. Congress recognized an alternative path to understanding the diverse international history and cultural heritage of the U.S.

A bi-national trail, three-quarters of which winds through the central highlands of Mexico, El Camino Real tracks a different European settlement story, one that emphasizes the shared history and heritage of Spain, Mexico and the American Southwest. The trail’s 16th-century origins pre-date both Jamestown and Plymouth Rock, while its historic faces, places and three-century legacy as a multiethnic point of cultural connection and exchange offer new touchstones of American history.

The “Royal Road to the Interior Land” reaches 1,600 miles north from Mexico City to West Texas and New Mexico. Its 400-mile thread through those states crosses deserts, rivers, mountains and more, from the lower El Paso Valley to the Mesilla Valley, from Socorro to Santa Fe to the pueblo of Ohkay Owingeh. Once part of Spain’s global network of roads and maritime routes, the route weaves European history into the fabric of American life, beginning with the 1598 Spanish settlement of New Mexico to the 1881 arrival of the railroad.

Although the railway overpowered El Camino Real’s primary transportation purpose, the trail’s cultural and commercial influences remain imprinted on the region’s physical landscape, social psyche and living history. Every wagon rut, earthen swale and gravestone is a record of the individuals who braved the trail to transplant their traditions and begin new lives in a foreign, faraway land. Modern highways now overlay some parts of the trail, but the historic buildings, archeological sites and natural landmarks that survive hold memories of the valiant lives and often-violent deaths that characterize El Camino Real’s north-south narrative.

Today, both Mexico and the United States honor and preserve the international legacy of El Camino Real. In 2010, UNESCO added sections of the Camino Real in Mexico to its prestigious World Heritage List. The designation highlighted five existing urban World Heritage sites that represent El Camino Real’s significant cultural, commercial, spiritual and geographical impacts, as well as 55 sites related to the use of the road—bridges, chapels, former haciendas and convents, natural landmarks and more. UNESCO further recognized El Camino Real’s “outstanding universal value” in linking Europe and the Americas through the human interchange of language, cultural traditions, rituals and objects of trade.

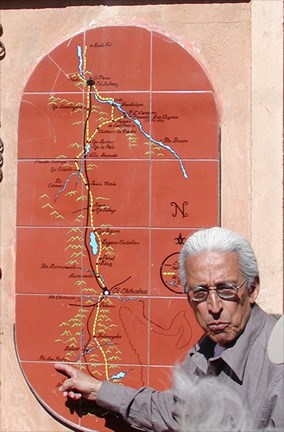

NPS Photo

El Camino Real’s designation as a U.S. National Historic Trail underscored the trail’s significance as North America’s longest cultural route and a vital commercial corridor for nearly 300 years. The Congressional act emphasized the preservation and protection of El Camino Real in New Mexico and West Texas, acknowledging the towns, villages, Indian pueblos and other historic sites along the trail as critical cultural and educational resources related to the history of the Southwest and the greater U.S. It also called for collaboration with Mexican counterparts working to preserve that portion of El Camino Real. More than a decade later, the protection and enhancement of the trail’s resources for public use in both countries are well underway.

Although not all parts of El Camino Real are accessible to the public, the 17 significant El Camino Real sites in New Mexico and West Texas highlighted in this travel itinerary challenge modern-day explorers to track their own path through the region’s contemporary cultural landscape. So strap on your hiking shoes and prepare for adventure. Embrace the quiet. Savor the scenery. Imagine life on the Royal Road.

A Royal Road

El Camino Real’s story begins with the 1546 discovery of a large silver vein in Zacatecas, Mexico. Twenty-seven years earlier, Hernán Cortés and his Spanish army had invaded Mexico, defeating the mighty Aztec Empire to control the region they called New Spain. The Spaniards’ mission was twofold: to exploit the region’s mineral wealth and to convert its native populations to Christianity. News of the rich mineral deposits at Zacatecas drew Cristóbal de Oñate, a Spanish soldier and aide to Cortés, 200 miles north from Guadalajara to develop the site. Together with Juan de Tolosa, Diego de Ibarra and Baltasar Temiño de Bañuelos, Oñate co-founded the city of Zacatecas in 1548. He became a powerful silver baron, and eventually, one of the richest men in New Spain.

With the colonization of Mexico came the development of a network of caminos reales, or royal roads, to serve the region’s transportation and communication needs. The name El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro initially identified a main thoroughfare that began to be developed in 1550 and was used to move silver from mines at Zacatecas, San Luis Potosí and Guanajuato south to the viceroyal capital of Mexico City. The original portion of the road, known as El Camino de la Plata (The Silver Road), ran southeast from Zacatecas to Ojuelos, Dolores Hidalgo, San Miguel de Allende and Querétaro. Presidios built along the route were to protect travelers from Chichimeca Indian tribes, whose territory El Camino Real encroached.

The Spanish silver rush inspired the construction of towns, churches, haciendas, government quarters, roads, bridges and other infrastructure to support Mexico’s burgeoning mining enterprises. As Spain’s mineral fortunes grew, so did the opulence of the buildings and cultural sites along El Camino Real’s path. Grand cathedrals and other structures largely constructed with forced Indian labor fused European architectural styles and Spanish religious art with local materials and artistry. Newly introduced livestock, agriculture and food products, tools and other material goods promoted a European quality of life in a land rich with its own established cultural traditions. As settlement, transportation and trade increased along El Camino Real, however, so did tensions.

By the late 16th century, El Camino Real stretched some 900 miles north from Mexico City to the frontier mining district of Santa Barbara in Nueva Vizcaya (modern-day Chihuahua). The century had seen a number of Spanish explorers—including Fray Marcos de Niza, Francisco Vásquez de Coronado, Fray Agustín Rodriguez, Francisco Chamuscado, Antonio de Espejo and Gaspar Castaño de Sosa—survey parts of New Spain’s northernmost frontier following different routes. Their travels revealed the existence of long-established Indian communities with extensive cultural, agricultural and ecological resources. Nonetheless, the region’s lack of mineral wealth left the Spanish Crown unwilling to commit fully to the area’s colonization.

Everything changed in 1595 when Cristóbal de Oñate’s nearly 50-year-old son, Juan, offered to finance a major expedition north. Born in Zacatecas, Juan de Oñate was raised between his family’s impressive estate at Pánuco, five miles north of Zacatecas, and a family home in Mexico City. Beyond the prestige of his family name, he brought military and administrative experience to the task. Furthermore, his marriage to Isabel de Tolosa Cortés Moctezuma, a descendant of the last Aztec emperor, reflected the unique cultural melding of the residents of New Spain. With King Philip II’s permission to proceed, Oñate recruited individuals of various ethnicities, including Indian and African, to accompany him to tierra incognita—a land unknown.

Among the recruits who departed Santa Barbara with Oñate in early 1598 were 129 soldiers and their families, Franciscan friars, farmers, laborers, servants and slaves. Traveling on horseback and on foot in a caravan of more than 80 ox-carts and mule-wagons with thousands of head of livestock, they blazed El Camino Real north through the Chihuahuan Desert. In late April, they crossed the Rio Grande at El Paso del Norte (The Northern Pass), in the area of today’s Ciudad Juárez. Following Mass and a feast shared with local Manso Indians, Oñate performed La Toma (The Taking), the ceremonial possession of Nueva México (New Mexico) in the name of Spain, the first European nation to stake a claim west of the Mississippi.

Gaspar Pérez de Villagrá’s 1610 epic poem "La Historia de la Nueva México" chronicles the Oñate expedition as the first record of the European colonization of the United States, predating Captain John Smith’s General History of Virginia by 14 years. Villagrá describes the group’s northerly migration as “a ship traversing unknown seas, set forth upon the trackless plain.” Indeed, as the travelers moved roughly parallel to the Rio Grande from El Paso to the river’s upper reaches, they forged the upper track of El Camino Real. Their route was not entirely new, however. It followed the pre-Hispanic trail along the Rio Grande, which had linked New Mexico’s pueblos and tribes to Mexican tribes and trading centers since at least the 13th century.

Not long into Oñate’s trek, at the upper end of the Mesilla Valley, Officer Pedro Robledo became the first European to die from the rigors of traveling El Camino Real on what would later become U.S. soil. Oñate memorialized his friend with a burial at a place he designated the Paraje de Robledo. The site was one of a series of parajes, rest stops or campsites, which would be established approximately every 10 to 20 miles along El Camino Real for travelers’ respite, refreshment and protection.

Two other parajes critical to the group’s survival were set at either end of the 90-mile desert shortcut that would become known as the Jornado del Muerto (the Journey of the Dead Man). Here Oñate steered the course away from the Rio Grande to save days of rocky riverside travel that precluded passage of heavy freight. The timesaver left the group without fresh water or animal forage and at risk of Indian attack. Traveling there on May 23, 1598, the group’s water reserves reached a dangerous low. When a roving dog discovered two pools of rainwater, they were saved. The Paraje del Perrillo (the Camp of the Little Dog), in the area now known as Point of Rocks, commemorates this life-saving event. Decades later in 1670, Bernardo Gruber, a German trader crossing the desert, was not so lucky. He is the dead man who reportedly inspired the desert’s daunting name.

Tales of struggle and survival characterized Oñate’s journey as he continued up El Camino Real—through the southern Piro Indian country to the middle Rio Grande Valley homes of the Tewa tribes, past the basalt beast of La Bajada escarpment and into present-day northern New Mexico. Relief was the predominant theme on August 18 as the expedition arrived at the pueblo of Ohkay Owingeh, on the west banks of the Rio Grande. Despite orders not to encroach on pueblo lands, Oñate, now Governor, proclaimed the village as San Juan de los Caballeros (St. John of the Knights), the capital of New Mexico and the northern terminus of El Camino Real. He later relocated across the river to Yungé pueblo, which he called San Gabriel de los Españoles (St. Gabriel of the Spaniards).

Connecting Cultures

Oñate’s successful incursion into New Mexico spurred the transformation of the area’s ancient Indian lands to a Spanish colony. The Spanish language was imposed on many Indian populations as their place names and landmarks were renamed. With the establishment of a strict trade monopoly by Spain, the pueblo Indian trail was usurped as El Camino Real, the main route for the importation and integration of Spanish goods and lifeways into the local landscape.

The road’s initial purpose was to supply the Spanish military and support the missionary effort. By 1609, official caravans of Franciscans and military officials were traveling north from Mexico City to northern New Mexico every three to seven years. Carrying as much as three tons of cargo, and averaging 10 miles a day, the one-way trip took about six months. Among the supplies transported were gilded altar screens, pipe organs and religious artworks to adorn churches constructed at pueblos along the Rio Grande. These massive buildings embodied the majestic mission architecture and religious traditions of colonial Mexico and Spain. They also represented the religious suppression of Pueblo tribes.

For Spanish settlers, El Camino Real was the bridge to preserving cultural and religious traditions, communicating with loved ones and maintaining a European cultural identity. The road delivered such luxury goods as wine, olives, nuts, chocolate, preserves, porcelain, silk and cast iron beds into the isolated frontier, as well as peaches, apples, chile, wheat and other crops. Livestock, including sheep, horses, goats, pigs and cattle, were transplanted via the trail, as were practical implements of everyday life. These included metal tools and weapons, new ways of building with earth, alternative acequia (irrigation ditch) systems and other agricultural technologies. New examples of weaving and pottery added to Pueblo Indian artistic traditions, while more intangible expressions in music, dance and literature permeated the cultural landscape.

Despite Oñate’s critical role in New Mexico’s colonization and first decade of development, his popularity among the military and the citizenry declined. In 1609, Pedro de Peralta replaced Oñate. The new governor’s first order of business was to move the provincial capital—and El Camino Real’s terminus—away from Pueblo lands and south to Santa Fe (Holy Faith), a small farming community established as early as 1605. Santa Fe’s 1610 designation as New Mexico’s capital distinguished it as the oldest capital city in what would later become the United States.

Peralta’s move reflected El Camino Real’s development as a network of flexible routes and side roads. These splintered off the main road to avoid challenging geographical or weather conditions, to serve emerging settlements, and to support the region’s long-term growth and survival. As Santa Fe matured into its capital status, with a stately governor’s palace (known as the Casas Reales), military presidio, adobe parroquia (parish church) and spacious central plaza, it connected to new communities north and south along El Camino Real. The road’s uses also evolved to meet the changing economic, military and cultural needs and initiatives that would push New Mexico forward.

By 1630, Spain’s Christian conversion of New Mexico’s native peoples was well underway with some fifty adobe and stone churches built at pueblos and Spanish settlements. While the path of El Camino Real had once exclusively served the Indian population, it was fully developed during the course of the century as a Spanish trade route used by all segments of the regional population. But unlike the towns accessed by stone roads and bridges along El Camino Real in central Mexico, New Mexico remained isolated. Rugged, unengineered dirt roads reached homes and churches. Built of adobe with flat roofs, vigas (ceiling beams) and spare detail, and often organized in defense-minded designs, the buildings expressed a more basic vernacular tradition that took creative advantage of local resources. In space and spirit, New Mexico reflected the gritty character and cultural melding of the frontier.

Conflict and Cooperation

Despite increased settlement, the frontier was dangerous. Apache, Navajo and Ute warriors continually threatened Spanish and Pueblo Indian lands, leaving the military focused on their defense. In an effort to maintain Spain’s stakehold, and to keep fearful settlers from abandoning the region, Spanish leaders sought to bolster the provincial economy by establishing a more regular system of trade on El Camino Real.

While the trail carried opportunity for Spaniards, it brought religious oppression, servitude, taxation and disease to Pueblo peoples who had once freely enjoyed New Mexico’s beauty and bounty. By the late 17th-century, Pueblo leaders had had enough. On August 10, 1680, several thousand residents from a majority of the pueblos attacked from all directions. They burned down the missions, killing 21 Franciscan priests and friars. They assailed outlying Spanish settlements, then converged on Santa Fe, where survivors took shelter with government officials in the Casas Reales. Nine days later, the Spaniards fled, following El Camino Real on foot 400 miles south to El Paso del Norte.

The most successful Indian rebellion in North American history, the Pueblo Revolt left the Spaniards in exile in what is now West Texas for the next 12 years. There, they and friendly Indian tribes, many of whom also fled the carnage, established the communities of Socorro del Sur, Ysleta del Sur, and San Elizario. In late 1692, newly appointed governor Don Diego de Vargas led a preliminary expedition back up El Camino Real into New Mexico. A year later, he and many of the exiled Spaniards made a permanent return to Santa Fe, forcibly ousting the Pueblo Indians from the Casas Reales. Even as they re-established control of Santa Fe, other Spanish and Indian refugees chose to stay in their post-revolt settlements in present-day West Texas.

Although a series of Pueblo rebellions continued through the 1690s, Spanish governance of New Mexico resumed as Franciscan friars rebuilt the Pueblo missions and other village churches. The promotion of Catholicism remained the Franciscans’ primary mission, but they interfered less with Pueblo religion and rituals, which were now practiced in tandem with Catholic traditions. By the mid-18th century, Spanish-Pueblo relations had taken on a more mutually tolerant tone. Territorial boundaries between each group were more clearly defined and abided, and the Pueblos more freely asserted their self-government and cultural identity. The Pueblos shared important Pueblo cultural assets with the Spaniards, including medicinal and culinary herbs, native paint pigments, buckskin clothing, and such mainstay crops as corn, potatoes and squash.

As a more symbiotic, socially integrated relationship developed between the Spaniards and the Pueblos, El Camino Real became more important to the prosperity of both groups. With the decreased emphasis on religious conversion, secular commerce and trade increased. Privately contracted caravans now traveled annually between Mexico City and Santa Fe. Among such critical cargo as mail and military supplies, these caravans brought valuable stocks of Asian and European goods into New Mexico, including glass beads, textiles, spices, silk and embroidered women’s shawls. In return, various efectos del país (products of the country)— sheep, wool, animal hides, blankets, salt and piñon nuts—were sent south to Mexico by local ranchers and merchants for sale at Mexican trade fairs.

Known as la conducta, loosely translated as a “community in miniature,” the local caravans had their departure celebrated as important and festive social events announced by a town crier and attended by crowds of well-wishers. The presence of military escorts that accompanied the caravans along every step of El Camino Real symbolized the commercial and cultural value of the caravans to individual New Mexicans and the collective provincial economy.

A New Mexican Lifestyle

According to historian and genealogist José Antonio Esquibel, five major waves of colonists traveled El Camino Real from Mexico to New Mexico between 1598 and 1821. The increased movement and interchange of materials and peoples along El Camino Real gave rise to a distinctive regional colonial culture. Its aesthetic and lifestyle blend European and Mexican influences with the original artistry and resourcefulness of frontier settlers, and endure in the region to this day.

While local Indian artistic traditions had thrived in the region for centuries, the need for innovation gave rise to a skilled Hispano artisan class. Locally produced santos (painted and sculpted images of saints), furniture, tools, textiles, jewelry and other devotional, decorative and utilitarian objects filled churches and households. Based primarily on traditional Spanish and Mexican designs, but made with local materials, these objects expressed a unique New Mexican character all their own.

With Mexico’s 1821 independence from Spain and the abolishment of longstanding restrictions on trade, the region’s singular cultural identity evolved further. The 1821 creation of the 800-mile Santa Fe Trail, which stretched west from Missouri to the Santa Fe Plaza, prompted Mexico to invite U.S. merchants to engage in commerce in New Mexico via El Camino Real, now designated as a camino nacional (national road). The move established New Mexico as an international port of entry into Mexico, inspiring an influx of Anglo-American settlers, traders and merchants to the region.

New Mexican residents now looked east for supplies, and Mexican and New Mexican merchants explored new sources of economic development. Inexpensive manufactured items such as calico cloth and ribbons, metal tools and hardware, and mirrors and glass became popular trade items in New Mexico. These often were the exchange for high-grade silver coin that was available in New Mexico and Chihuahua City, the latter of which developed into an important trail terminus in Mexico. El Camino Real between Santa Fe and Chihuahua became known as the Chihuahua Trail.

New Mexico’s rule under the Mexican government was short lived. In 1846, U.S. Brigadier General Stephen Watts Kearny followed the Santa Fe Trail to the Santa Fe Plaza, where on August 18, the American flag was raised above the old Casas Reales. He then followed El Camino Real south at least as far as El Cerro de Tomé, a major El Camino Real landmark, before heading west to California.

The troops that remained in New Mexico also understood El Camino Real’s vital transportation role, further improving and developing the roadway for military use. On a hillside in Santa Fe, on the day after Kearny’s invasion, construction began on Fort Marcy as the Army’s defensive hub in the new American Southwest. The 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which set the terms for New Mexico’s 1850 designation as a U.S. Territory, codified their takeover. That same year, Texas gave up its fight with the U.S. government to claim a large portion of New Mexico as its own. The culturally affiliated communities of Socorro del Sur, Ysleta del Sur, and San Elizario. on the southwest stretch of El Camino Real in the U.S. became part of Texas nonetheless.

New Mexico’s transition to a U.S. territory spurred further growth in trade along the Santa Fe and Chihuahua Trails and increased military efforts to protect El Camino Real cargo and travelers from Indian attack. The U.S. built a string of notable forts and garrisons along El Camino Real between Socorro and El Paso del Norte, including Fort Fillmore, Fort Craig and Fort Selden, which were supplied by El Camino Real caravans. After the 1861 launch of the Civil War, El Camino Real provided the path for a Confederate invasion of the Union-affiliated New Mexico. Confederate troops captured Fort Fillmore south of Las Cruces, but ultimately, Fort Craig’s strategic El Camino Real location helped weaken Confederate forces before their final defeat at Glorieta Pass.

New Beginnings for El Camino Real

Even at the time of the ratification of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, plans were underway to develop a western railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean. By 1878, the train had arrived at Raton Pass. In 1880, it reached Santa Fe, and by 1881, the rail lines extended to El Paso. Carrying in boxcars what mules and oxen had once hauled in wagons or on their backs, the train with unparalleled ease and speed rendered El Camino Real and the Santa Fe Trail obsolete. Trainloads of manufactured goods and new residents gave way to new economic initiatives, including the development of a tourist industry, and ultimately, New Mexico statehood in 1912.

During the ensuing years, El Camino Real receded back into the earth. Through disuse, erosion and statewide development, its once-prominent physical impacts on the landscape faded to gentle swales, linear traces, earthen mounds, hoof-worn stones and artifact scatters. However, people could not ignore its timeless ingenuity and practicality as a primary transportation corridor.

By 1905, the Territorial Assembly had established New Mexico’s first modern highway, New Mexico Highway 1, roughly along its route. Other urban roads and highways subsequently followed El Camino Real routes. Busy Interstate 25 now runs parallel to the original trail as it cuts a north-south swath through the center of the state. In the spirit of El Camino Real, these roadways move modern travelers to their important destinations and discoveries as they continue to shape the melting pot of the American Southwest.

While firmly rooted in the past as a National Historic Trail, El Camino Real today moves forward as a living trail. Its centuries-old pathways still nurture a lively exchange of ideas, customs, language and camaraderie among peoples on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border. Every trekker who walks the trail in the footsteps of those who came before becomes part of El Camino Real’s history. Everyone who leaves his or her own footprints in the trail dust becomes part of its future.

Explore more history by visiting the El Camino Real travel itinerary website.

Tags

- el camino real de tierra adentro national historic trail

- el camino real de tierra adentro trail

- historic trail

- heritage travel

- heritage tourism

- heritage travel itineraries

- discover our shared heritage travel itineraries

- texas

- texas history

- new mexico

- new mexico history

- spanish missions

- spanish mission church

- national trails

Last updated: July 12, 2020