Part of a series of articles titled Harney Re-Examined: A New Look at a Forgotten Figure.

Article

Harney Re-Examined Part II: Harney's Treatment of Native Americans

In 1837, Harney was given a command in the Seminole War, a campaign to expel indigenous people from their Florida homelands. For several years, Harney’s men saw little combat, mostly patrolling and maintaining military outposts, but following an ambush of his forces by the Seminole leader, Chakaika, he disregarded the established norms of warfare to gain vengeance. Harney promised freedom to an enslaved man who served as his guide. During the pursuit, he and his troops disguised themselves as Native Americans. While Harney watched from a treetop, his men snuck into a Seminole camp and hung eight men "to the top of a tall tree" while their wives and children were forced to watch them die. Harney let his soldiers know he approved by "ma[king] the island ring with his cheering." In the wake of these summary executions, the St. Augustine Times called Harney “a man who knows his duty to country and is not afraid to perform it.”

Harney’s next major command was in Oklahoma, where he was appointed the commander of Fort Washita, an outpost created to mediate between the Chickasaw and Choctaw people who were violently and forcibly relocated during the Trail of Tears, and the Southwestern tribes whose traditional homeland they now lived in. On July 5, 1844, after enlisted men J.H. O'Brien and Private Sylvanus Bean refused orders to dig a latrine and insulted their commanding officer, Harney grew enraged by their insolence. Harney grabbed O'Brien's hair, threw him to the ground, and thrashed him with his cane, causing wounds that left O’Brien in the infirmary for a week. Harney ordered Bean to be shackled with a ball and chain and fitted with a spiked collar, which he had to wear during 27 days of hard labor. At this time, Harney also owned a group of muscular male slaves who he enjoyed provoking into fistfights with soldiers known for brawling.

These violent activities led other officers to complain that Harney’s "arbitrary and unmilitary conduct" was not in keeping with "good order and military discipline.” Harney was subsequently court martialled on June 6, 1845. Harney defended himself as being merely "naturally boisterous" while "serv[ing] my country to the best of my abilities." Harney was convicted and sentenced to a four-month suspension but Winfield Scott, the highest-ranking officer in the US military, suspended Harney's sentence because he thought it not sufficient punishment for Harney's "vicious habits", although he found no way to dismiss Harney from service.

In 1846, as the United States prepared to invade Mexico, Harney was given a frontline command but disobeyed direct orders, crossing the Rio Grande and attacking Mexican forces before other troops had assembled. Harney faced another court martial where he was found “guilty of disobeying direct orders” but once again escaped punishment.

Harney earned accolades for his bravery in combat. However, during the occupation of Mexico City, he sparked international controversy for his handling of an incident involving two American citizens who had detained Marie Courtine, a French citizen accused of assaulting the Mexican wife of an American. When Harney told the Americans, "There is my backyard, you can take them in and do with them what you please, I shall not interfere,” the French ambassador complained directly to American President, James Knox Polk, who reprimanded Harney for his actions.

After the Mexican-American War, Harney and his soldiers forcibly dispossessed indigenous people who lived in the newly conquered territory. While pursuing Lippan and Caddo people in the winter of 1853, Harney ordered his troops to "exterminate all the men and make the women and children prisoners." In 1855, following a confrontation in which the Brulé band of the Sioux nation defeated a US army detachment that had invaded their village and opened fire after they refused to surrender a tribal leader, Harney was promoted to the rank of brigadier general and commanded to “operate against the hostile Indians” so that settlers heading west could safely build farms and ranches in indigenous lands.

As Harney prepared for combat, he hoped "to attack any body of hostile Indians, which I...may chance to encounter" and hoped that by separating Native Americans from their families they "would be obliged to surrender themselves or incur the risk of starving." On September 2, 1855, Harney and his troops reached the junction of Blue Water Creek and the North Platte River where a village of 250 people stood. Harney marched his men by night and positioned them to ambush the residents of this village. By 4:30 AM, Harney and his men were in place.

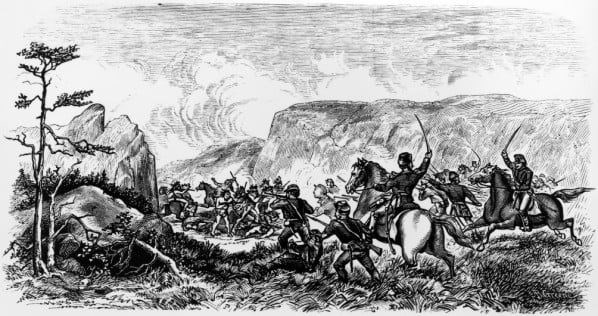

As day broke, Harney and his soldiers neared the village. The Native American leaders, Little Thunder, Spotted Tail, and Iron Shell approached Harney, hoping to arrange peace or at least buy time for their women and children to flee, but Harney refused to talk. Even after the village elder, Little Thunder, displayed a white flag, Harney refused to shake his hand and told Little Thunder that the "day of retribution" was upon him and his people "must fight" Harney's men. As Little Thunder returned to his village, Harney ordered his infantry to charge, while his cavalry blocked any possible retreat. As Harney's men fired on them, Native American women and children hid in small caves carved into a rocky gorge. One soldier said that watching the wounded women and children die “was heart rending."

Harney, however, was proud of his actions. After the battle, he was alleged to have said, “I have come to kill Indians, and believe it is right and honorable to use any means under God’s heaven to kill Indians. Kill and scalp all, big and little; nits make lice.” The New York Times reported on this battle that: “The lamentable butcheries of Indians by Harney's command on the Plains have excited the most painful feelings.” “The so-called battle was simply a massacre, but whether those Indians were really the same who have cut off emigrant trains with so many circumstances of savage cruelty, or whether it is [even] possible to distinguish between the innocent and the guilty in retaliating these outrages.” The Sioux people gave Harney the nickname, “The Butcher” and “The Big Chief who Swears” in the wake of this violent massacre.

During and after his lifetime, Americans honored William Harney’s legacy by naming places after him. One such place was Harney Peak, the tallest mountain in South Dakota, which in 2016 was renamed Black Elk Peak, after a lobbying campaign led by Native American historians. However, many place names still bear Harney’s name. In San Juan County, Washington, Harney Channel between Orcas and Shaw Islands used to honor his name but has been renamed to honor Henry Cayou, a Native American leader. In Oregon, Harney County, Harney Lake, and Portland’s Harney Street and Harney Park pay tribute to William Harney. Across the river from Portland, in Vancouver, WA (home of Fort Vancouver National Historical Site) the neighborhood of Harney Heights and Harney Elementary School commemorate Harney. The town of Harney, Nevada, Omaha’s Harney Street, Florida's Lake Harney, Harney Point, and Harney River in Everglades National Park also honor William Harney. Many of these place names are in areas where Harney was active during his military career.

Last updated: July 15, 2022