Last updated: May 20, 2024

Article

The Historic American Buildings Survey's 90th Anniversary

For ninety years, the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) has been the at the forefront of recording America’s rapidly vanishing built environment, embracing buildings ranging from the architect-designed and monumental to the humble vernacular to tell all American stories. Over 45,000 buildings and sites are now represented in its archive of measured drawings, photographs, and historical reports.

Established during the Great Depression, HABS was a call to action spurred by the loss of America’s early architectural landscape, a concept that remains relevant today. It was the first time that the federal government took action to recognize and protect the nation’s architectural legacy. It also laid the groundwork for many preservation initiatives to come, establishing practices and concepts such as field survey, listing, and providing information on historic sites for the public benefit.

In this article, you will see how HABS has adapted these new technologies to our workflow, as well as some of the challenges faced along the way. You will also see how HABS continues to expand the breadth of its collection: from the addition of once-cutting edge Mid-Century Modern designs, to the critical task of recording and preserving sites pivotal to the American Civil Rights Movement.

The history of the built environment is inextricably intertwined with the stories of the people who constructed and used it; HABS documentation thus serves as a mirror, reflecting the nation’s achievements and aspirations, successes, and failures, as well as our everyday lifestyles and folkways.

Ellis Island Main Hospital

New York Harbor, New York 2014

Image from HABS

The Main Hospital on Island 2 was constructed in three phases between 1900 and 1909 for the Immigration Bureau of the Department of Commerce and Labor in consultation with U.S. Marine Hospital and Public Health Service (US-MHPHS) surgeons assigned to medical inspection at the Ellis Island U.S. Immigration Station. Immigrants arriving at Ellis Island needing general medical attention were treated here, as well as groups eligible for USPHS care such as merchant seaman. The Main Hospital included a maternity ward, operating rooms, an x-ray laboratory, and later a dental clinic.

Technology: Creating a “Backbone”

Image from HABS.

Learn More

See the HABS documentation of the Main Hospital building and other historic sites at Ellis Island, part of the Statue of Liberty National Monument in the HABS/HAER/HALS Collection in the Library of Congress here.Fort Jefferson

Dry Tortugas, Florida 2015

Todd Croteau, Photographer.

Historical Significance

Fort Jefferson was built to fortify the harbor of the Gulf of Mexico and to serve as an advance post for ships involved in maritime trade. Although begun in the late 1840s, it was still incomplete in the 1860s when Florida announced its secession from the Union, followed months later by the outbreak of the Civil War. Fort Jefferson then served as a coastal blockade for Union naval forces and as a military prison. Advancements in weaponry quickly made Fort Jefferson obsolete, and the military abandoned it in 1874.

Images by HABS

Technology: Dealing With Large Sites

For very large sites, using a surveying total station to create a fixed network of targets increases both efficiency and accuracy. While a laser scanner is itself a highly accurate piece of technology, a total station is an order of magnitude more accurate, because it is designed specifically to take individual measurements over extremely long distances. Instead of connecting laser scans only to each other via shared targets, it is possible to attach them to a network of total station targets that are given priority over scan-to-scan targets in the software. This increases the overall accuracy of the assembled point cloud.

Image by HABS

Learn More

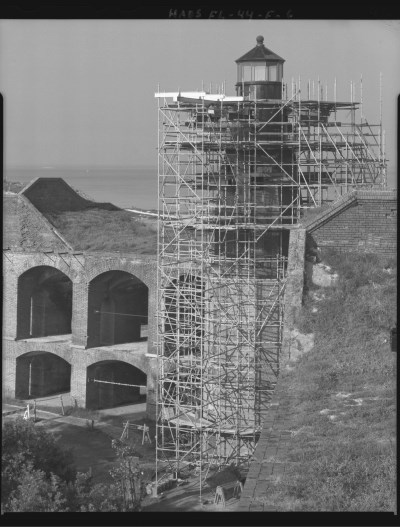

See the HABS documentation of Fort Jefferson and other historic sites at Fort Jefferson National Park in the HABS/HAER/HALS Collection in the Library of Congress here.Fort Jefferson – Harbor Light

Dry Tortugas, Florida 2015

Jarob Ortiz, Photographer.

Technology: Going Back for More

Image by HABS

Learn More

See the HABS documentation of Harbor Light and other historic sites at Fort Jefferson National Park in the HABS/HAER/HALS Collection in the Library of Congress here.Cape Hatteras Lighthouse

Buxton, North Carolina 2016

Image by HABS

Historical Significance

Cape Hatteras Lighthouse is an important aid to the navigation of the Atlantic Coast: the Diamond Shoals that extend up to ten miles out from Cape Hatteras, coupled with the Gulf Stream currents, earned this area its reputation as the “graveyard of the Atlantic.” A lighthouse was first established here in 1803, heightened in 1853, and finally replaced with the current lighthouse in 1869-70. Due to the intense need for visibility at long range, Hatteras is the tallest brick light tower in the United States. For recognition during daylight, it is painted with distinctive black and white spirals. The lighthouse was first documented by HABS in 1989, prior to being moved due to coastal erosion.Technology: Vertically Challenged

digital SLR camera attached to a pole. (Center) Photogrammetric model of the intricate, cast iron supports below the lantern catwalk. (Right) Detail of the lantern, based off of a of laser scan & photogrammetry.

Images by HABS

Learn More

See our virtual tours, panoramic photos, and animations of high-definition point cloud data, of the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse here.See the HABS documentation of the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse and other historic sites at Cape Hatteras National Seashore in the HABS/HAER/HALS Collection in the Library of Congress here.

National Zoo – Reptile House Washington, DC 2017

Images by HABS

Historical Significance

As director of the National Zoological Park from 1925 to 1956, Dr. William M. Mann sought to transform it from a menagerie-style collection of animals to a world-class institution. Completed in 1931, the Reptile House evoked scientific progress, world exploration, and a fascination with the exotic. Its Byzanto-Romanesque design, a departure from the earlier zoo buildings, was a collaboration between Director Mann and Washington, D.C. Municipal Architect, Albert Harris. The brick exterior is enlivened with cast stone snakes, lizards, and frogs, and a colorful prehistoric scene in concrete mosaic above the front door. Likewise, it provided then state-of-the-art environments for reptiles in captivity, with each cage including a diorama of the environment from which the reptile came. It became a model for American zoos throughout the 1930s, demonstrating that the National Zoological Park was an influential, first-rate public institution.Technology: Photogrammetry

Image from HABS

Learn More

See the HABS documentation of the Reptile House and other historic sites at the Smithsonian's National Zoological Park in the HABS/HAER/HALS Collection in the Library of Congress here.Hollin Hills – Model 2B42LB

Fairfax County, Virginia 2017

Justin Scalera, photographer

Historical Significance

Built in 1953, this house represents the most popular prototype created by locally prominent architect Charles Goodman (1906-92) for his progressive mid-century modern subdivision of Hollin Hills. Built between 1946 and 1956, Goodman’s Hollin Hills houses used standardized plans and prefabricated modular unit construction. Although only eight “unit types” were developed, by changing the orientation to fit the natural topography, and utilizing optional rooms and design features, it is rare that any two houses look exactly alike. Situated in lush, rolling, and wooded terrain, Goodman worked with renownedlandscape architect Dan Kiley to blend the houses with the natural environment.Collection Highlight: Modernism

Photos from HABS

Learn More

See the HABS documentation of Model 2B42LB and other historic houses in Hollin Hills in the HABS/HAER/HALS Collection in the Library of Congress here.ANC Memorial Amphitheater Arlington, Virginia 2018

Render by Paul Davidson

Render by Paul Davidson

Learn More

See the HABS documentation of the ANC Memorial Amphitheater and other historic site at Arlington National Cemetery in the HABS/HAER/HALS Collection in the Library of Congress here.Civil Rights Trail Various locations in Alabama 2019

Jarob Ortiz, photographer

Historical Significance

HABS documented twenty-two sites that are part of the Alabama African American Civil Rights Heritage Sites Consortium. They include National Historic Landmarks such as the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, a site of civil rights meetings that was bombed by the Ku Klux Klan in 1963 killing four young girls and prompting international condemnation of segregation; and the Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church where pastor Martin Luther King organized the Montgomery Bus Boycott that led to the desegregation of city buses.

Jarob Ortiz, Photographer

MLK Jr. Life House Atlanta, Georgia 2020

Image by HABS

Historical Significance

This was the family home of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Coretta Scott King starting in 1965. Instead of moving to a middle-class Atlanta neighborhood or suburb, they chose a ca. 1933 house in Vine City, a predominantly poor neighborhood on Atlanta’s west side. While in decline during the 1960s, Vine City was also close to King’s alma mater, Morehouse College, and home to other black professional and civil rights leaders. The Kings hired African American architect Joseph W. Robinson to design two ambitious renovation efforts between 1964 and 1968 that transformed the 1930s cottage into a 1960s ranch house with a two-car garage, a master bedroom suite addition, and basement recreation room and offices. This was the only house the Kings ever owned, and it immediately became a center of their civil rights work. Dr. King lived here until his assassination in April 1968 and his wife Coretta Scott King until 2004, raising their four young children and, in 1968, starting the King Center in its basement offices.Collection Highlight: Civil Rights Sites

(Left) Jarob Ortiz, Photographer. (Right) Rendering by HABS

Learn More

See the HABS documentation of other historic sites at Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site in the HABS/HAER/HALS Collection in the Library of Congress here.Beatty-Cramer Farm House Frederick County, Maryland 2020

Justin Scalera, photographer

Historical Significance

Technology: Speed Demon

HABS recently acquired one of the newest-generation laser scanners, the RTC360, which is fast enough to efficiently scan interiors room by room: it can complete a 360-degree scan in less than two minutes, far faster than hand-measuring. At Beatty-Cramer we used the larger and slower (but longer-range and more accurate) P50 to scan the exterior, while the RTC360 made quick work of the interiors.Kennedy Center Washington, DC 2021

Jarob Ortiz, Photographer

Historical Significance

The Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts is the official national memorial honoring 35th U.S. president John F. Kennedy. It is an iconic example of the work of Edward Durell Stone, an internationally recognized master architect of the Modern Movement. It reflects a form of modernism known as New Formalism that used classical elements and strict symmetry to create monumental buildings.

Jarob Ortiz, Photographer.

Hirshhorn Museum Washington, DC 2022

Jarob Ortiz, Photographer

Historical Significance

Jarob Ortiz, photographer

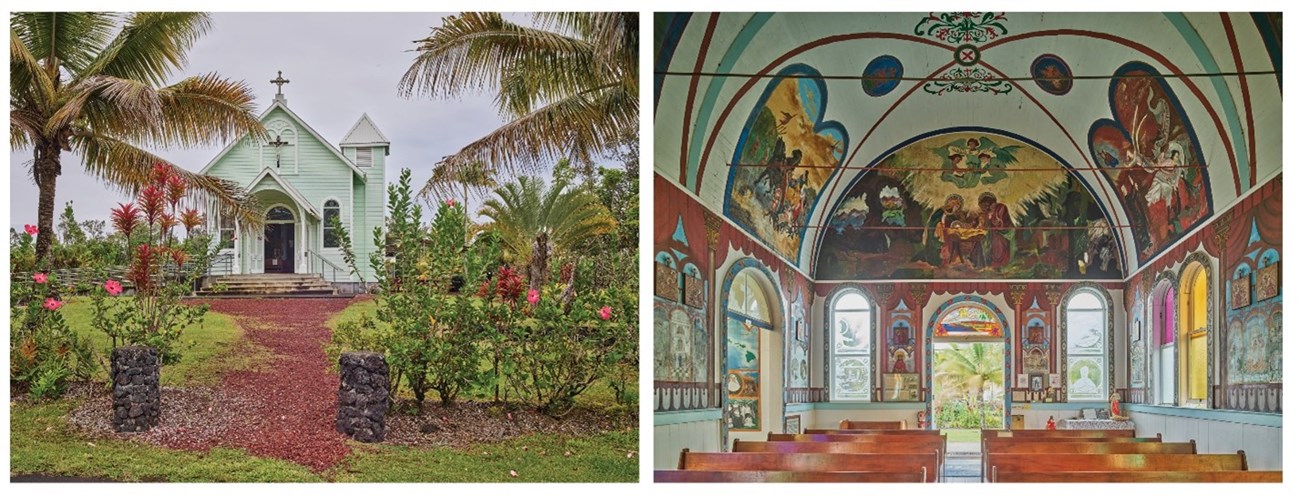

Painted Churches Hawaii 2022

Justin Scalera, Photographer

Historical Significance

HABS photographed two simple, gothic-influenced Hawaiian churches beautifully embellished with hand-painted interior murals. St. Benedict’s Painted Church in Honaunau, built in 1899, includes murals depicting scenes from the bible and lives of saints painted in 1899-1902 by Father John Velghe. Star of The Sea in Kaimu features decorative interiors by Belgian Catholic missionary priest Father Evarist Gielen, who also oversaw construction of the church, in 1927-28. The Star of the Sea paintings tell the story of Father Damien, a Belgian priest who helped leprosy patients on the island of Molokai and later died from the disease himself.Art Deco and Modern Hawaii, Hawaii 2022

Justin Scalera, photographer

Historical Significance

Working in concert with the local AIA, HABS identified noteworthy buildings in Hawaii to photograph for the collection. They range from religious and residential to industrial and governmental buildings. Many were in Modern styles indicative of the period of development in the region.

Justin Scalera, Photographer.

Rio Vista Farm Socorro, Texas 2022

Justin Scalera, photographer.

Historical Significance

The Rio Vista Bracero Reception Center is the best preserved of numerous such complexes established by the Mexican Farm Labor Program to bring workers into the U.S. from Mexico. Operating between 1951 and 1964, the program supplied nearly one-quarter of U.S. agricultural workers and significantly impacted Mexican immigration and post-war increases in the Latino population.

(Left) Justin Scalera, Photographer. (Right) Robert Arzola, Photographer.

West Texas Various Locations in Texas 2022

Justin Scalera, Photographer

Historical Significance

While in El Paso on the Rio Vista Bracero project, HABS photographed twenty sites in and around the city, recommended by local preservation organizations. Many were commercial buildings within the downtown associated with the local Latino population, such as those in the Duranguito neighborhood, which is one of the oldest in downtown El Paso. Religious buildings included the modest adobe La Isla Church, built for a local farming community, and the eye-catching 1962 Mid-Century Modern Temple Mount Sinai synagogue designed by Los Angeles architect Sidney Eisenshtat. Examples of civic architecture include the Presidio County Courthouse in Marfa. The work of influential local architect Henry Charles Trost was also photographed, including his own Prairie Style house. Short form historical reports will be prepared by students from Texas A&M University at El Paso’s Historic Preservation Department to accompany the photographs into the collection.

Justin Scalera, Photographer

Heritage Documentation Programs (HABS/HAER/HALS): Documenting America's Built Environment

The Heritage Documentation Programs (HDP) consist of the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS), Historic American Engineering Record (HAER), and Historic American Landscapes Survey (HALS). The programs document historic sites and structures across the United States through the creation of measured drawings, large-format photographs, and historical reports. Documentation is archived in the HABS/HAER/HALS Collection at the Library of Congress and is available to the public without restriction. HDP is part of the National Park Service’s Cultural Resources, Partnerships, and Science Directorate.Learn more about the history and work of the Heritage Documentation Programs by visiting our website here.

HABS/HAER/HALS Collection

The HABS/HAER/HALS Collection at the Library of Congress is the nation's largest archive of historic architectural, engineering, and cultural landscape documentation. It is an active collection that grows each year. The collection includes measured and interpretive drawings, large-format black & white and color photographs, written historical and descriptive data, and original field notes. The collection is designed to permanently record the breadth of American places, and to make this documentation available as widely as possible. As of 2023, more than 45,000 sites are included in the collection. Materials created for HABS, HAER, or HALS are in the public domain.Search the Collection

Search the HABS/HAER/HALS Collection at the Library of Congress.

About this Article

Text and images for this webpage represent a condensed version of the exhibit “Blazing the Trail: The Historic American Buildings Survey turns 90.” The exhibit was part of the Roger W. Moss Symposium, “Documentation by Design: A Celebration of The Historic American Buildings Survey 90th” celebrated November 10–11, 2023 at The Athenaeum of Philadelphia.Tags

- ellis island national park

- cape hatteras national park

- hatteras light

- dry tortugas national park

- ellis island hospital

- fort jefferson

- habs

- historic preservation

- hdp

- architecture

- historic architecture

- technology

- history

- lighthouse

- civil rights

- drawings

- habs drawings

- measured drawings

- military history

- maritime history

- farmhouse

- martin luther king

- mlk

- historic house

- laser scanning

- photogrammetry

- documentation

- cultural heritage

- modernism

- fieldwork

- amphitheater

- cemetery

- arlington national cemetery

- farmworker

- built environment

![Ellis Island Main Hospital Color laser scan images showing an exterior elevation above a building section. Both of these images are above a black and white floor plan.]](/articles/000/images/ellis-composite.jpg?maxwidth=1300&autorotate=false)