Last updated: October 21, 2024

Article

Texas Tortoise Monitoring at Palo Alto Battlefield National Historical Park: Results for 2023

NPS photo / GULN staff

Project Background and Methods

The Texas tortoise (Gopherus berlandieri) is a small, cryptic tortoise of south Texas and three states in Mexico that is threatened by widespread habitat loss and illegal collection. There is only one U.S. National Park unit where this species is commonly found, Palo Alto Battlefield National Historical Park (NHP) in Brownsville, Texas. The tortoises that live on the park do not face the same immediate threats as those occurring on unprotected lands, but even so, their abundance, health, and local movements require monitoring to support future management decisions.

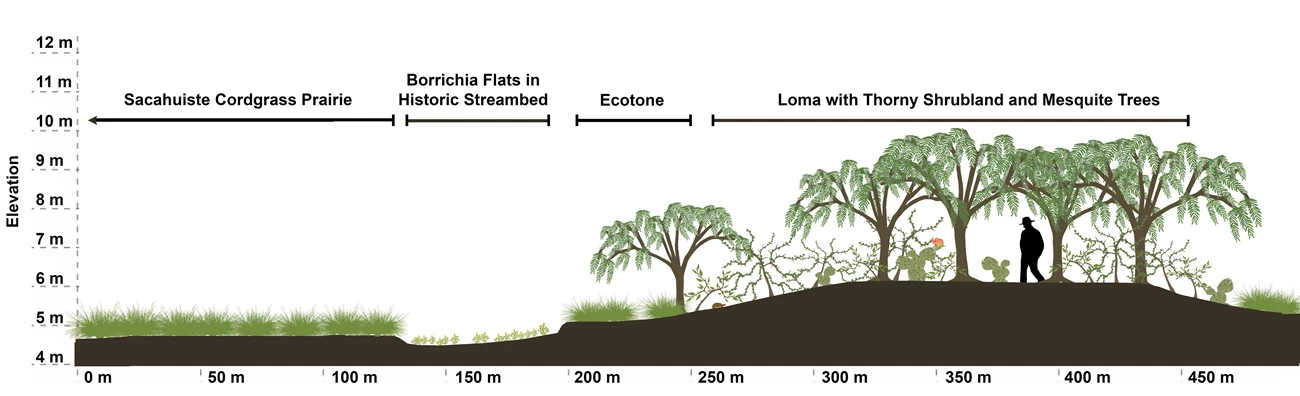

The Texas tortoise monitoring project was established in 2008 by the Gulf Coast Network, part of the National Park Service’s Inventory and Monitoring (I&M) Program. The goals of the Texas tortoise monitoring project are to: (1) track the tortoise’s status in seven permanent, 4-hectare sampling units, in terms of catch per unit effort, movements, body condition, and the distribution of sizes and sexes captured, and (2) analyze cross-year trends in abundance and survivorship from mark-recapture data. The Texas tortoise monitoring project is a long-term mark-recapture study, where field crews conduct standardized tortoise surveys once each year, always for the same amount of time and within the same seven survey units. The survey units are located on lomas, which are low ridges covered in thorny shrubs and mesquite trees, the tortoises’ preferred habitat in coastal Texas (see Figure 1 for a schematic of a park loma and its adjacent habitats).

Sampling events occur over a three-day period each fall. All seven units are surveyed twice over this period, each time by a different team that dedicates eight person-hours of effort to each unit, or about two hours for a four-person team. As team members encounter tortoises, they weigh them, measure their carapace dimensions, photograph them, record their sex, and record a GPS location. For newly encountered individuals, they mark them by drilling holes in scutes according to a unique numeric code, to allow for identification upon recapture (Figure 2). The park’s Texas tortoises have been surveyed, marked, and measured like this at least once per year for 15 years; however, the total effort, survey areas, and written protocols have changed over time. The current protocol, Version 3.0, was published in 2018. Previous annual reports for this project as well as other information can be found in the Gulf Coast Network Inventory and Monitoring Texas Tortoise Monitoring Project on the NPS DataStore or the network's website for the Texas tortoise project.

NPS photo / GULN staff

2023 Trip Summary

The Gulf Coast Network completed its Fall 2023 Texas tortoise monitoring trip from October 30 to November 2. Thirteen participants were split into two teams, each surveying all seven units for the required eight person-hours of effort, or a total of 16 person-hours, with the two surveys conducted one to two days apart. The 2023 trip also included four surveys that were not part of routine fieldwork. These non-focal surveys, called bonus surveys, each received a total effort of eight person-hours. These bonus survey units were located in four previously-identified areas of the park that, like the seven primary units, had relatively high elevations and apparently suitable vegetation. The intent was to check for previously-marked tortoises that may have moved to areas not normally surveyed.

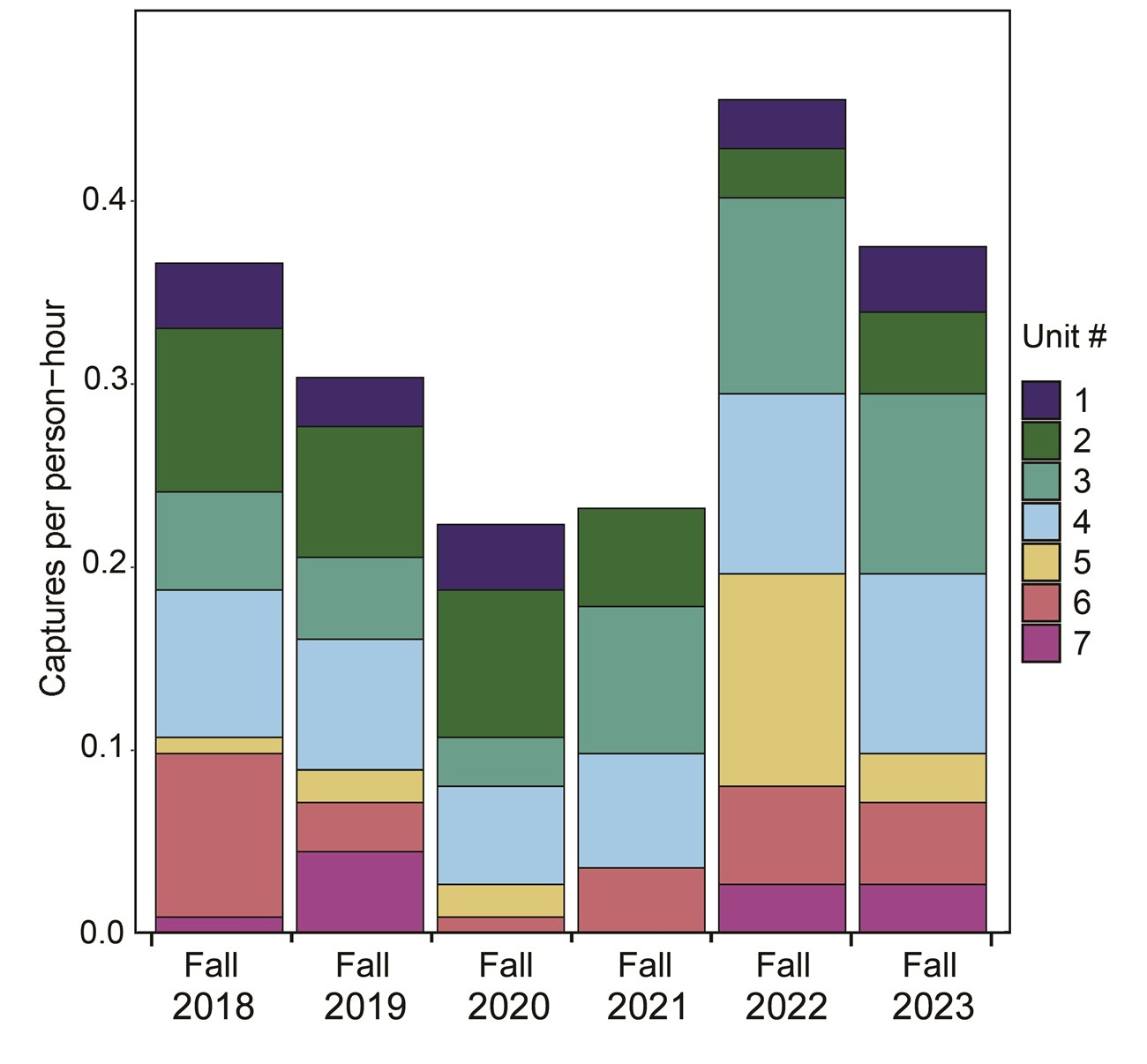

The Fall 2023 trip yielded 60 unique live tortoises, although 18 were found during bonus surveys or were outside unit boundaries or survey times (Table 1). This amounted to 42 individuals found over 112 person-hours within time-and-area constrained surveys, or a catch-per-person-hour-effort of 0.38. This was the second highest yield since protocol version 3.0 was implemented in Fall 2018 (Figure 3).

Table 1. Live, unique tortoises found both in and out of surveys. Each individual tortoise was only counted only once, even if it was seen during both surveys. Total counts of individuals were then summed for all seven units, for a combined tally of tortoises across both teams. The total includes a separate tally of newly marked individuals for 2023 ("new"), in addition to the combined total that also counts tortoises recaptured from previous years. The table does not include four dead tortoises found during surveys (one dead unmarked and three dead marked).

| Areas | Female | Male | Juvenile | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| During surveys in the seven focal units | 17 | 24 | 1 | 42 (11 new) |

| Bonus surveys or outside survey boundaries | 8 | 9 | 1 | 18 (9 new) |

| Total live individuals | 25 | 33 | 2 | 60 (20 new) |

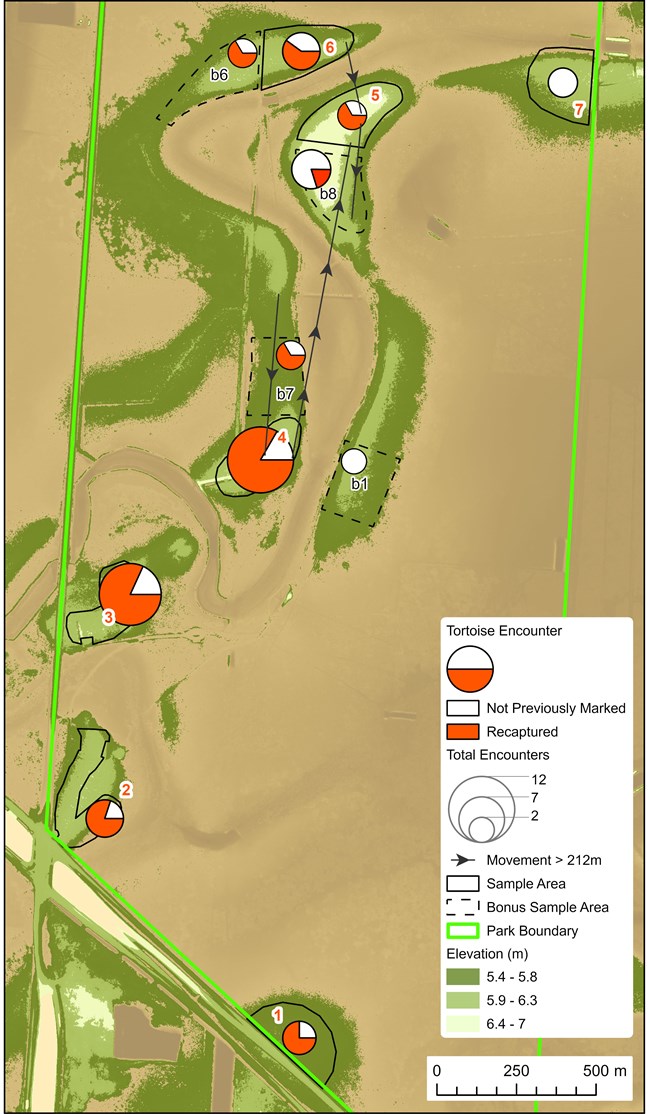

Twenty tortoises were newly marked during the trip, with the trip’s final new ID being 350. Eleven newly-marked tortoises were found during focal (non-bonus) surveys, and nine were found during bonus surveys (Figure 4). This relatively high number of new encounters, about one in four within focal surveys, is consistent with previous surveys. The regular occurence of new, adult individuals during annual surveys suggests tortoises are somewhat transient within units. Even with small home ranges, some animals likely slip in or out of survey units from trip to trip.

The map includes encounter data and locations of the 7 primary sample areas as well as the 4 bonus areas surveyed in 2023.

The 42 tortoises found during survey events were distributed unevenly among units, as were the newly marked individuals joining the project this year (Figure 4). The greatest yields were in units 3 and 4 with eleven unique individuals each, which was more than double that of any remaining unit. Each of the two high-yielding units contributed two newly marked individuals. Units 1, 5, and 7 had the lowest yields, at three or four individuals each. The three lowest-yielding units in 2023 also had relatively low yields over many of the previous survey events within the last six years (Figure 3). It is not fully understood why some units have lower yields than others, but potential causes include differences in plant communities on the lomas, past agricultural impacts, and the degree of invasion by the non-native Guinea grass (Urochloa maxima).

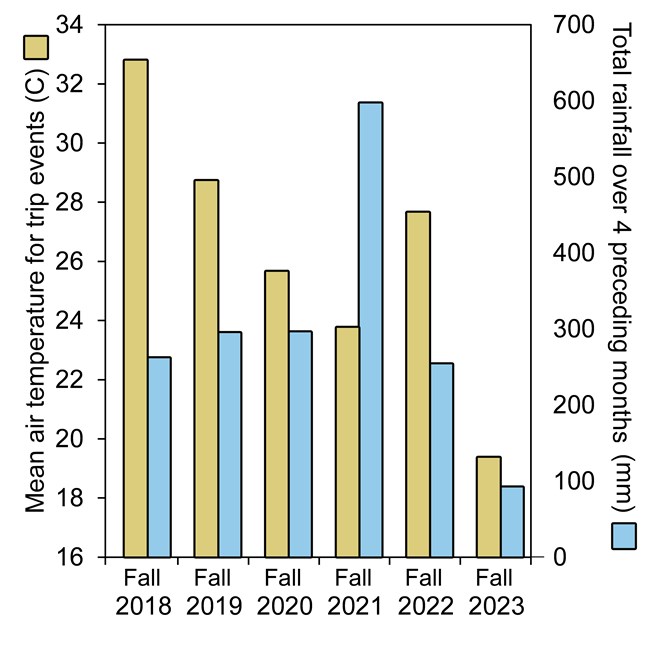

Since monitoring began at Palo Alto Battlefield NHP, tortoise yields have fluctuated from one year to the next. This has remained true across the six events since the most recent protocol was implemented in Fall 2018 (Figure 3). Although the exact causes are not understood, two environmental variables are known to influence tortoise behavior and detectability: temperature and precipitation. Temperature has a more instantaneous impact, where animals become inactive or increasingly sheltered when too hot or cold. Meanwhile, the vegetation response to precipitation is slower, and it impacts the quality and quantity of forage as well as overall detectability. This year’s survey was particularly cold and dry relative to other survey events (Figure 5).

Cooler temperatures meant that animals were less active and potentially harder to detect in their resting places. However, drought conditions and advanced plant senescence increased ground visibility for surveyors, which likely improved detectability, even if animals were sheltered. Preliminary analyses using satellite-based measures of vegetation 'greenness' (i.e., NDVI or EVI) partially support this, in that crews tend to detect more tortoises during survey events when park vegetation is under drought stress and appears less green overall. However, since tortoises can easily move in and out of the loma-centric survey areas, higher detections may also (or instead) be an indication that more tortoises are present on monitored lomas at those times. See Supplemental Materials for more information.

Notable Observations from Fieldwork

Movements: A tortoise’s location is recorded each time it is encountered. The straight-line distance between two consecutive encounter locations is defined here as a movement. Since 2008, the Gulf Coast I&M Network has recorded 673 movements. Most were relatively short, with a median of 47.9 meters (157.2 feet). A small subset of movements were much longer, however, defined here as this project’s top 95th percentile of movement distances (> 212 meters [695.6 feet]). In this survey trip, four tortoises moved more than 212 meters. Two of the four moved from one habitat unit, or isolated loma, to another. One of these tortoises moved into unit 5 from unit 4, and the other tortoise moved into unit 5 from unit 6 (Figure 4). In both cases, the tortoises had to cross a low, sparsely vegetated area with a historic streambed, which during wet periods would likely deter movement. The other two of the four movements were within the same piece of continuous loma habitat and did not require streambed crossing. Three of four tortoises with longer distance movements for 2023 had last been seen in 2021, and the fourth had last been seen in 2016.

Tortoise Pairs: The teams recorded five tortoise pairs within 2 meters (6.6 feet) of each other, which could be due to courtship activity. In four cases, a male was with a female, and in one case, two males were together.

Dead Tortoises: Four dead tortoises were found on this trip. This is higher than the project’s average of two dead tortoises per trip, but it is not an alarming mortality rate. Three of these animals were previously marked, with prior encounters occurring in 2020 and 2021. The fourth dead tortoise was a juvenile.

Time Between Encounters: While some tortoises are seen almost every trip, it is not uncommon for an animal to go “missing” from the project for many years. Nine of this survey’s tortoises were missing for five or more years, including one not seen for nine years and another for eleven years!

Casual Observations

During a tortoise survey, participants may write down wildlife sightings besides tortoises or record other observations that seem interesting or unusual. These observations are informal and do not have a direct bearing on tortoise analysis, but they may provide informative or at least entertaining context to survey reports. Notable species observed by crew members in 2023 are listed below.

Native Species

- Diamondback rattlesnake (Crotalus atrox)

- Texas indigo snake (Drymarchon melanurus erebennus)

- Schott’s whipsnake (Masticophis schotti)

- Texas spiny lizard (Sceloporus olivaceus)

- Rose-bellied lizard (Sceloporus variabilis)

- Yellow mud turtle (Kinosternon flavescens)

- Red-eared slider; dead (Trachemys scripta elegans)

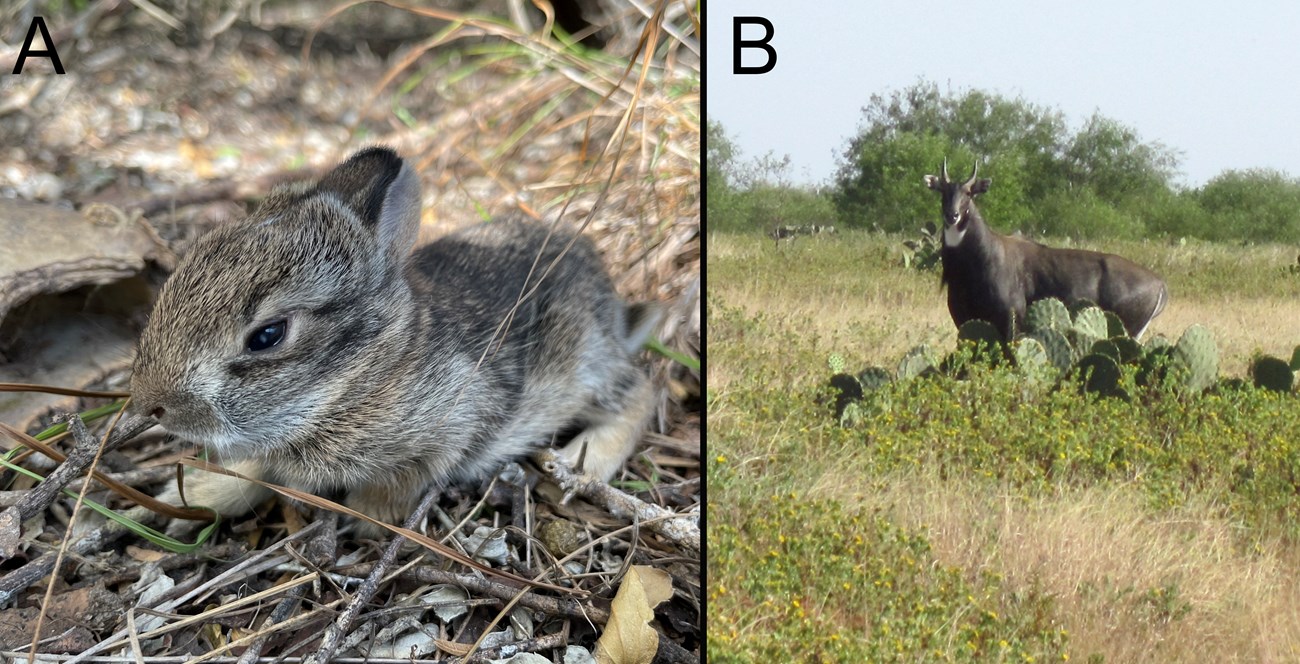

- Eastern cottontail rabbit (Sylvilagus floridanus, Figure 6A)

- Javelina (Tayassu tajacu)

- Hispid cotton rat; dead (Sigmodon hispidus)

- Southern plains woodrat (Neotoma micropus)

- Striped skunk (Mephitis mephitis)

Non-Native Species

- Bearded dragon (Pogona vitticeps). One individual, apparently a released pet, was encountered during a Texas tortoise survey. The individual was returned to captivity.

- Nilgai (Boselaphus tragocamelus; Figure 6B). This non-native species is seen regularly in the park, typically in small herds.

NPS photo / GULN staff

The Gulf Coast Network’s next tortoise survey trip will occur in the fall of 2024 and will mark the 16th year of our mark/recapture monitoring project at Palo Alto National Battlefield NHP. The landscape surrounding the park continues to develop, and area-wide, Texas tortoise habitat continues to shrink. The park maintains a sizable population of tortoises, but long-term monitoring is important to understand how external pressures will impact the park’s population of this iconic south Texas species.

Other Briefs and Summaries in this Series

Carlson JE. 2023. Trip Report for Tortoise Monitoring at Palo Alto Battlefield NHP 2022. Gulf Coast I&M Network, Lafayette, LA

Bracewell J and Carlson JE. 2022. Comparison of Vegetation Structure in Texas Tortoise Habitats using LiDAR. Gulf Coast I&M Network, Lafayette, LA

Carlson JE. 2022. Resource Brief: Texas Tortoise Program Summary. Gulf Coast I&M Network, Lafayette, LA

Carlson JE. 2022. Trip Report for Tortoise Monitoring at Palo Alto Battlefield NHP 2021. Gulf Coast I&M Network, Lafayette, LA

Carlson JE. 2021. Trip Report for Tortoise Monitoring at Palo Alto Battlefield NHP 2020. Gulf Coast I&M Network, Lafayette, LA

Reference & Supplemental

Supplemental materials to this report are available in the NPS datastore, as are all previous project brief. Follow the link below for the 2023 Supplemental Materials (NPS internal downloads only) and links to all other project materials.

Open Transcript Open Descriptive Transcript

Transcript

The sounds of a texas tortoise walking on bare ground.

Descriptive Transcript

This tortoise was found in his natural habitat at Palo Alto Battlefield NHP during the 2023 NPS I&M annual monitoring event. A crew member weighed him, measured him, and then drilled uniquely-identifiable holes at the edge of his carapace. In the video, he has just been released, and he stands up and starts walking.

- Duration:

- 15.478 seconds

This tortoise was found in his natural habitat at Palo Alto Battlefield NHP during the 2023 NPS I&M annual monitoring event. A crew member weighed him, measured him, and then drilled uniquely-identifiable holes at the edge of his carapace. In the video, he has just been released, and he stands up and starts walking.