Last updated: January 22, 2024

Article

Ranching at Grant-Kohrs National Historic Site

NPS / M. Surber

The wide vistas of "Big Sky" country in Montana offer expansive views of sweeping prairies, rolling hills, and distant mountains. White clouds travel across open sky, their shadows playing across the vast stretch of grass below. That beautiful image belies a harsh environment of hot, steamy summers and cold, bitter winters, capable of both rainy deluge and persistent drought. Settlers with a strong will and entrepreneurial spirit built their legacy from this landscape, leaving their mark on the patterns of agricultural and economic development in the region.

The Grant‐Kohrs National Historic Site landscape offers a glimpse into ranch practices from the open range days of the 1800s through the modernization of ranching practices in the early to mid‐1900s. Through interpretation and demonstration, the working ranch demonstrates how ranch craft evolved to meet the demands of an industrializing society, contend with the privatization of property and limitations to use of public lands, and capitalize on advances in technology and science.

NPS / M. Surber

The working and residential landscapes and buildings at the site preserve the personal and practical lives of ranch inhabitants, the culture and practice of ranching in early 1900s Montana, and the history of Grant-Kohrs Ranch.

Farming and Ranching through History

The Grant‐Kohrs National Historic Site is located in the Deer Lodge Valley in western Montana. The valley, shaped by retreating glaciers at the end of the last ice age, is bisected by the meandering Clark Fork River and flanked by Mount Powell and Thunderbolt Mountain. The valley has been inhabited and used by native peoples for thousands of years. In the decades leading up to European colonization, the site was home to tribes such as the Pend d’Oreille, Flathead, and Shoshone. Archaeological sites throughout the valley demonstrate the area’s importance for hunting, trade, and shelter.

European settlers in search of prosperity saw opportunity in in this region. The Gold Rush brought people through Montana on their way to the west in search of fortune, and the lure of vast swaths of open, inexpensive land attracted farmers and ranchers hoping to grow a prosperous business. As populations of white settlers flooded into the region, tensions over territory increased.

As the region's population grew, methods of land management and business practices changed, modernizing to adapt to an evolving market and changing environment. Changes within the valley echo larger patterns of settlement and growth in the American west. The character of this change is easily discernable in the evolution of the Grant‐Kohrs site: from ad‐hoc trade and commerce, to fully fledged cattle empire, to modern ranch.

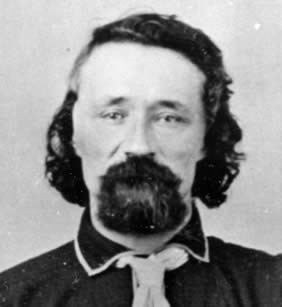

Johnny Grant: Establishing the Ranch

NPS / Grant–Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site

Johnny Grant arrived in the Deer Lodge Valley in the mid‐1800s, setting up a trading post in Deer Lodge Valley to make money off the gold seekers, cattlemen, and tribal populations within the region. Grant was the son of a French-Canadian fur trader. Born and raised on the frontier, he was at home in the company of traders and tribes prevalent in the valley at the time of his arrival. Grant convinced other traders to settle near him, forming a small community of European, Mexican, and French‐Canadian businessmen. Grant married women from several local tribes, strengthening his relationships with the local Indigenous people.

NPS / M. Surber

Though investments on his ranch and farm were varied, his greatest success was in cattle. He began by trading road-weary cattle for his own rested and well‐fed specimens. His herd grew, fattened off the open Montana grassland.

His success allowed him to build the first permanent structure in the valley, and in 1862 he hired craftsmen to build the house which is now the center of the NPS property. This large house, often cited as one of the finest and largest in the Montana territory at the time, was surrounded by log structures and tipis, providing a focus for a large family and employee group.

Grant said, "I always minded my own business, treated everybody alike rich or poor, white or black, and after I became rich an Indian was just as welcome to my house as a white man."

Though successful in business, Grant felt increasingly out of place as populations grew and new laws were established. Though he spoke many languages fluently, his heritage and accent were obstacles to dealing with new settlers from the east, and he soon began to feel like an outsider at his residence. Despite a short tenure in the area, he sold the ranch to Conrad Kohrs in 1866.

NPS / Grant–Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site

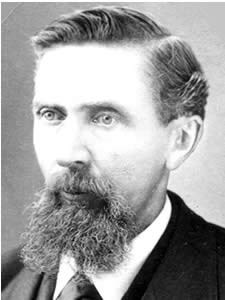

Conrad Kohrs: Development of the Ranching Industry

Conrad Kohrs was already successful in his own right, raising cattle to supply gold prospectors and passing settlers. With the addition of Grant’s land and stock, Kohrs capitalized on open range methods and animal husbandry practices to create a cattle empire, eventually becoming known as the Cattle King of Montana.

Augusta, Conrad’s wife, oversaw the management of the household. In her hands, Grant’s original house became a showcase of Victorian style complete with fine, imported furnishings and lush gardens. The house operated as more than just a home. It was the center of the ranch operation and a boarding house for visiting businessmen.

NPS / Grant–Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site

The surrounding landscape also underwent a transformation during this time (between 1868 and the mid-1880s), evolving from a relatively rustic house to a residence that reflected domestic refinement. Augusta Kohrs maintained several gardens, and they both contributed to the design and construction of lawn, trees, and a picket fence. The domestic landscape was not entirely separate from ranch operations, however, and by the end of the 1800s the lower ranch yard was congested with agricultural and ranching outbuildings and a complex of fences and roads.

With the help of his half‐brother, John Bielenberg, Kohrs expanded his herd and carefully managed their range to ensure the health of both the cattle and the grassland. With no fencing and, in many cases, few written property records, the Montana territory offered wide open land for use in grazing cattle. Herds ranged, browsing on rich native grasses and forbs.

As this style of ranching became more popular and herd size grew, the value of the rangeland suffered. A brutal winter in 1886 spelled disaster for many ranchers. Kohrs managed to save his ranch by leveraging his assets, but many others were completely ruined and abandoned ranching altogether.

Kohrs and Bielenberg recognized their methods would need to change if their business was going to last. They began the slow shift to fenced pasture and hay production. Though this meant they did not have the vast range available to them, they were able to fatten their cattle by focusing efforts on hay and grain cultivation, irrigation, and careful breeding practices. They capitalized on the proximity of the railroad to solidify their relationship with distant markets like those in Chicago, ensuring a market for their beef.

They also acquired new acreage around the home ranch, increasing range land while also giving them access to water sources and water rights for irrigation purposes. By 1908, the total property around the home ranch was approximately 22,307 acres.

Conrad Warren: Making of a Modern Ranch

NPS / Grant–Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site

Conrad Warren, grandson of Conrad and Augusta Kohrs, came to manage the ranch in the late 1920s. Warren’s father was a physician, and his interest in scientific methods and veterinary medicine are attributed to this background. Warren rebuilt the ranch's stock, growing herds which had dwindled in the later years under his grandparents' supervision. Warren introduced purebred stock, creating a herd of certified animals with registered lineage. He introduced Belgian draft horses to the ranch, breeding purebred bloodlines through carefully managed breeding practices. He also introduced modern medical practices, including inoculation and artificial insemination.

NPS / M. Surber

NPS / M. Surber

To increase grain and hay production, Warren expanded and improved irrigation practices, contouring the land to capitalize on water retention. He purchased a tractor and a mechanical thresher, reducing the human power that was necessary to bring in each year’s grain crop. Warren’s efforts streamlined the processes of both ranch and farm. Charles Morrow Wilson visited the ranch in 1937, writing in a magazine article:

The old ranch, once a vast area of wild grass, is now dotted with fattening pens, haystacks, sheds, granaries, and small barns. It means that a shiny, new three‐ton truck and a fleet of horse‐drawn hay wagons rumple over the landscape… It means a shedful of the latest styles in farm machinery, numerous gasoline and electric motors, a crew of cowboys who have learned to double as farm hands, veterinarians, milk‐maids, and nursemaid to mothering cows…

Warren had brought a new era of farming practices to the site, one which largely echoes what we know today.

The landscape shows evidence of the development of Western ranching history, shaped through the legacy of these three owners.

The ranch was born through the actions of Johnny Grant at a time when the West was home to a wide range of Indigenous and emigrant inhabitants. Conrad Kohrs and John Bielenberg managed the ranch during the height of the open range period and through its evolution into fenced, controlled ranch practice. Conrad Warren saw the fruition of that evolution and guided it toward modern ranching techniques.

The character of the ranch over time also reflects its place in the backdrop of the changing Montana territory and the wider landscape of the western United States.

Grant‐Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site: History in Action

NPS / M. Surber

Today, the National Park Service is responsible for stewardship of this ranch and farm. The NPS uses the site as a living museum, maintaining agricultural and ranching practices from several periods through the mechanisms of a working ranch.

Park staff maintain a herd of Hereford, Shorthorn, and Longhorn cattle on site. The herd is cycled through the hay fields and holding pens. Interpretive activities offer an opportunity to learn more about ranch culture and historic practices. Visitors can learn about branding techniques and haying, or watch experienced handlers demonstrate herding and roping techniques on well-trained stock horses.

Hay crops are cultivated and harvested using various historical methods. Belgian and Percheron draft horses pull threshing equipment and hay wagons and operate harvest equipment. Equipment that is used during demonstrations is generally typical of the late 1800s and includes horse-drawn mowers, buckrakes, side-delivery rakes, dump rakes, and the Beaverslide Hay Stacker.

Guests may tour the fully-furnished Grant‐Kohrs house and gardens and experience the luxurious surroundings cultivated by a successful family over many years. A museum storage facility at the site houses a collection of artifacts and records related to the ranch history and culture and Montana history.

NPS / M. Surber

-

Grant-Kohrs Ranch Cultural Landscape Report, Part Two: Treatment Recommendations (2017)

-

Grant-Kohrs Ranch Cultural Landscape Report, Part One (2004)

-

Cultural Landscapes Inventory: Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site Landscape (2007)

-

Cultural Landscapes Inventory: Kohrs Ranch House and Yard (2004)