Last updated: March 1, 2022

Article

Geraldine M. Bell

Geraldine “Geri” Bell grew up in the Philadelphia area with her parents and two sisters. Her mother worked at a dry cleaners and her father at a bakery. In a 1985 oral history Bell describes her mother as the strong one in their family. Throughout her high school years, Bell was one of only a few Black students in the school; in college she was one of four in a class of 400. She graduated from Immaculata College with a BA in history in 1967.

Before graduation, Bell took the Civil Service entrance exam. She was offered positions with five federal agencies. She chose the National Park Service (NPS), thinking they would make her a smoke jumper, as that is all she knew of the bureau. Instead, she started as an interpreter at Independence National Historical Park the day after graduation. She saw it as a short-term job to earn money towards her goal to join the Peace Corps.

Bell did just that, leaving the NPS in September 1967. She was sent to Cameroon, West Africa. She was the only Black Peace Corps volunteer in her group. She was assigned to a rural health program for pregnant women and babies. She served there for two years and became fluent in French. She explained that during her time in Africa she went “from being a Black female in America—and there’s something wrong with that—to being an American in Black Africa—and there’s something wrong with that. So, where do you belong?”

Following the Peace Corps, Bell rejoined the NPS as a park technician at Independence in June 1970. She gave guided tours, including a few in French. She said, “I don’t recall that the park had changed a lot” while she was gone, and she worked with many of the same staff. In 1985 she recalled “a distinct image for the females who worked as interpretive staff at the park as hostesses. Now that could be from my 1967 experience because at that time our uniform resembled an airline hostess. You couldn’t eat a banana split and button your jacket after lunch.”

In January 1972 she attended training at the NPS Horace M. Albright Training Center. She and Lillie Howse were the first two Black women to attend courses there. Bell noted, “Albright was an eye-opener in terms of learning about a national system, that this place is related to those other Park Service places.” With the other class participants she undertook mountaineering, repelling, and camping. Bell noted, “I found that even people who didn’t know much about Black folks were at least willing to talk to me.”

After completing the course, she was assigned to the NPS Western Regional Office in San Francisco for eight months in their Public Affairs Office. Her position included shadowing her supervisor to learn the skills of a public affair officer. She also gave a three-week tour of federal land management agencies in California and Nevada to African women students arranged by the NPS Office of International Affairs. The second major event she recalls from this period was the Second World Conference on National Parks at Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks. She worked the conference as a bilingual translator. Following the conference, she provided the interpretive narration on a bus tour around California for international conference participants. She remarked, “It was kind of nifty being the only Black person people could think of because you got to do really weird stuff.”

The intake program sent her to Saratoga National Historical Park in September 1972. Her job title was junior historian, but she also supervised seasonal employees and managed the park library.

In 1975 she returned to Independence, this time as a supervisory ranger. She was the first Black woman in the position at the park. She was responsible for interpretation at Independence Hall, Congress Hall, Old City Hall, Liberty Bell Pavilion, and Graff House. Bell organized her staff of 15 women and nine men guides (and 16 more hired during the height of the festivities) to handle millions of visitors who came to the park in 1975 and 1976 for the bicentennial of the Declaration of Independence. In a single day, she and her staff guided 22,000 people through the Liberty Bell Pavilion. In her 1985 oral history interview she admitted to sometimes not wearing her name tag on her uniform to avoid hearing visitors joke about the connection between her surname and where she worked.

After the bicentennial events, in addition to her other duties, Bell was assigned to the NPS study team evaluating a proposed Afro-American museum in Ohio in 1977 and 1978.

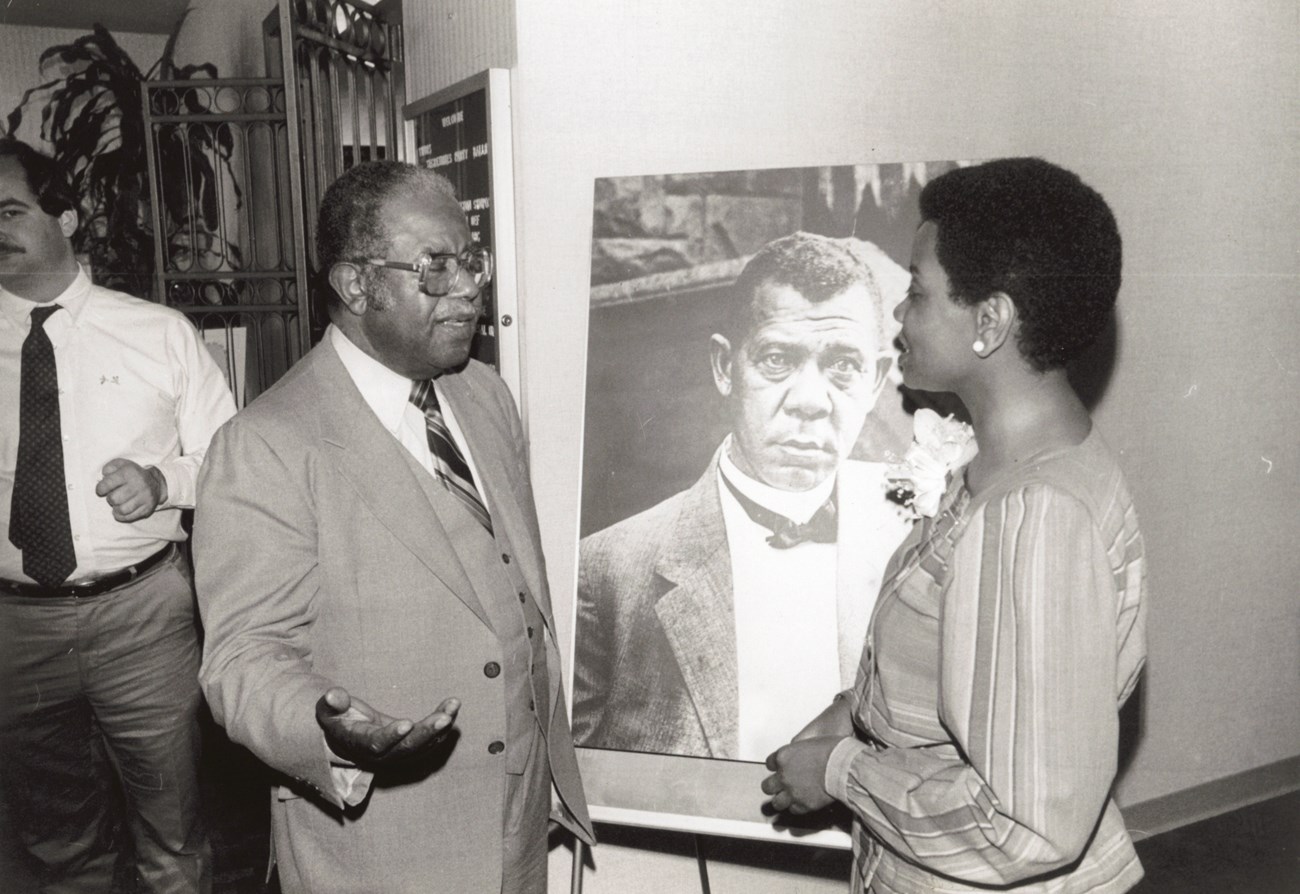

Bell became superintendent at Booker T. Washington National Monument on November 4, 1979. At the time NPS Director William J. Whalen stated, “Gerri was the best qualified of the 14 talented candidates we considered for this superintendency.” Although Bell recalls that there might have been a Black woman serving as an acting superintendent before her appointment, she was the first Black woman to be named superintendent in the NPS.

Asked in 1985 if she thought the NPS was a male-oriented organization and whether it had changed during her career, Bell replied, “Well, we can wear pants now, right? And we can wear the hat. Holy, Mary. Big accomplishments here. Yes, I think it was and still is. Sometimes its hard to tell when you are dealing with the male barrier and when you are dealing with the bureaucracy because it is so staffed with males. Would it be any different if you had females? I don’t feel the [gender] thing as much as the racial things. My suspicions are not based so much on the [gender] things as the racial things and the bureaucratic things.”

As a single woman in the NPS, Bell found the entertaining aspect of being a superintendent challenging and rarely did it. “I don’t have time for myself. The job eats all my time and I think it eats all my time because I don’t have a family that is equally demanding. If I did, I think the time would be more balanced but then it still wouldn’t be for me, it would be for the family.”

She also reflected, “People think I’m younger than I am and I don’t know if that has any connection with the way they treat me as the manager. They’re waiting for the man to show up, then I show up. I’ve had people come to look for Mr. Bell. That kind of reaction to the fact that this ‘kid female’ person is in charge. Also, everybody is Mrs. I’m always called Mrs. Bell. I’m seldom called Ms. Bell.”

Ms. Bell was superintendent at Booker T. Washington until April 23, 1988.

Sources:

“Afro-Am Museum Study Has Begun.” (1977, April 19). Xenia Daily Gazette.Bell, Geraldine interview. (1985, June 12). Polly Kaufman Papers. NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry Center.“Geraldine M. Bell Appointed as Superintendent at Booker T. Washington National Monument, Virginia.” (1979, November 17). The Atlanta Voice.

Kaufman, P. (2006). National Parks and the Woman’s Voice: A History. University of New Mexico Press.

National Park Service. (1979, December). “Bell New at Booker T. Washington.” Courier: The National Park Service Newsletter, 2 (14), p. 15.

National Park Service. (1980, February). "People on the Move." Courier: The National Park Service Newsletter, 3 (3), p. 19.

National Park Service. (1988, December). “News.” Courier: The National Park Service Newsletter, 33 (12), p. 23.

“Wilberforce Museum to be Studied.” (1977, April 15). Marysville Journal-Tribune.

Williams, Edgar. (1976, February 12). “History Gets a Guiding Hand in Tours at Independence Hall.” The Philadelphia Inquirer.

Explore More!

To learn more about Women and the NPS Uniform, visit Dressing the Part: A Portfolio of Women's History in the NPS.

This research was made possible in part by a grant from the National Park Foundation.