Part of a series of articles titled People of the Oregon Trail.

Article

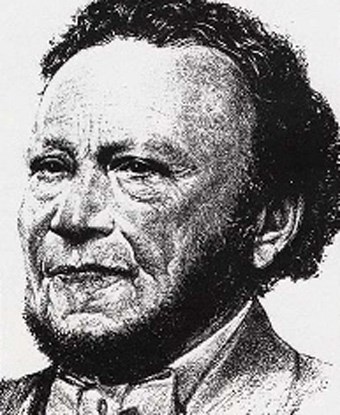

George Washington Bush, the Oregon Trail

Image Courtesy of the Henderson House Museum

George Washington Bush – Oregon Trail[1]

By Angela Reiniche

George Washington Bush, a free Black Missourian who had become wealthy in the region’s cattle trade, loaded his white wife and their five children onto a wagon at Savannah Landing in the spring of 1844; they joined a train of eighty-four wagons headed towards Oregon Country and the Columbia River Valley led by Michael T. Simmons, an Irish immigrant. After netting about two thousand dollars in silver coin from the sale of their farm, Bush and his family were in better economic shape than most of their fellow travelers; in fact, Bush—who managed six wagons of his own—helped at least two cash-poor white families in their group buy supplies for the trip.[2] Perhaps owing to his experience serving under Andrew Jackson at the Battle of New Orleans in 1815, Bush advised the young men in his party to always have their guns and ammunition ready, whether for their defense or sustenance. A fellow traveler overheard Bush tell the boys, “take my advice: anything you see as big as a blackbird, kill it and eat it.”[3] Bush’s reputation for generosity and fairness served him well when he faced challenges at the far western end of the trail.

During his trip west, Bush befriended John Minto, a young English emigrant who frequently mentioned Bush in his diary of their party’s overland travel. For example, Minto recalled that by the time they had reached Fort Bridger, an important outfitting post in present-day Wyoming, the company—which had split from a larger train—was in crisis as most in the party were out of supplies and clothing. Bush’s generosity, however, saved the day. He purchased flour, sugar, and yards of calico at inflated prices so that the party could be clothed and fed.

Minto’s recollections also demonstrate his companion’s understanding of the challenges he might face when they reached Oregon: “Not many men of color left a slave state so well to do, and so generally respected; but it was not in the nature of things that he should be permitted to forget his color. ...he led the conversation to this subject. He told me he should watch, when we got to Oregon, what usage was awarded to people of color, and if he could not have a free man's rights he would seek the protection of the Mexican Government in California or New Mexico.”[4]

En route to Oregon Country, the party learned of a new law that denied Black people the right to settle there. For this reason, the Simmons party headed north of the Columbia River Valley, refusing to settle anywhere without the Bush family.[5] Two years after the Bush-Simmons party settled on Puget Sound, the United States and Britain reached a settlement over the disputed Oregon boundary. George Washington Bush and his family were suddenly subject to Oregon law, jeopardizing the status of their land claim. Nevertheless, Bush prospered and continued to help out his neighbors during their hard times. Historian Shirley Ann Moore shares an especially poignant story about a time when Bush could have made a great deal of money selling his wheat to speculators but chose instead to share it with his neighbors, who could not afford the exorbitant prices. He told the prospective wheat buyers that he would rather give what he had than see his neighbors want for food.[6]

In 1853, twenty-five white Oregonians petitioned the territorial legislature to ask Congress to validate the Bush family’s land claim. The following year, Michael Simmons—who had made the overland journey with Bush a decade earlier and now served in the legislature— sponsored the proposal to allow the exception. The bill passed and the Bushes were awarded a 640-acre homestead in an area known today as “Bush Prairie,” near present-day Tumwater, Washington. Once settled, the Bush family became renowned for their skills and generosity, often distributing their crops among less fortunate neighbors. Additionally, they introduced the region's first sawmill, gristmill, mower, and reaper. George Washington Bush died in 1863, the same year that President Abraham Lincoln delivered the Emancipation Proclamation. Bush’s sons carried on their father’s tradition of both public service and farming.[7]

[1] Part of a 2016–2018 collaborative project of the National Trails- National Park Service and the University of New Mexico’s Department of History, “Student Experience in National Trails Historic Research: Vignettes Project” [Colorado Plateau Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit (CPCESU), Task Agreement P16AC00957]. This project was formulated to provide trail partners and the general public with useful biographies of less-studied trail figures—particularly African Americans, Hispanics, American Indians, women, and children. Thank you to the Oregon-California Trails Association for providing review of draft essays.

[2] William Loren Katz, The Black West: A Documentary and Pictorial History of the African American Role in the Westward Expansion of the United States (1971; repr. and revised, New York: Broadway Books, 2005), 62; and Shirley Ann Moore, Sweet Freedom’s Plains: African Americans on the Overland Trails, 1841–1869 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2016), 67–68.

[3] Katz, The Black West, 63; and Moore, Sweet Freedom’s Plains, 121; and John Minto, “Reminisces of Experience on the Oregon Trail in 1844,” Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society 2, no. 3 (September 1901): 212–241.

[4] Minto quoted in Katz, The Black West, 64.

[5] Katz, 63.

[6] Moore, Sweet Freedom’s Plains, 70–74; and Katz, The Black West, 65.

[7] Katz, The Black West, 64.

Last updated: March 7, 2023