Last updated: August 16, 2024

Article

From Idea to Implementation: The Making of a Citizen Science Project

Tim Watkins

Stephanie Letourneau and Zoe Brumbaugh watched with a mixture of anxiety and elation as a team of teenagers navigated the rocky shoreline at Frazer Point in Acadia National Park. The volunteers were quiet, still adjusting to the early-morning start. Fog obscured the horizon and the water gurgled as it receded to low tide. Their search for sea stars and other marine life was about to begin.

This moment was a culmination of Brumbaugh and Letourneau’s work as ecology assistants in the Scientists in Parks (SIP) Program. While spending the summer at Schoodic Institute, they took on a range of projects in the intertidal zone of Acadia, a park with 60 miles of coastline. One of their tasks was to design monitoring protocols that would be performed by park visitors with Earthwatch Institute, an organization that pairs volunteers with scientists around the world to conduct environmental research.

This moment was a culmination of Brumbaugh and Letourneau’s work as ecology assistants in the Scientists in Parks (SIP) Program. While spending the summer at Schoodic Institute, they took on a range of projects in the intertidal zone of Acadia, a park with 60 miles of coastline. One of their tasks was to design monitoring protocols that would be performed by park visitors with Earthwatch Institute, an organization that pairs volunteers with scientists around the world to conduct environmental research.

Schoodic Institute/Shannon O’Brien

But until this summer, neither had taken a citizen science project all the way from idea to implementation.

Taking the First Step

Tim Watkins

In the face of these ongoing environmental challenges, long-term citizen science projects allow researchers to understand change on an extended time scale and to detect shifts in the ecosystem that may otherwise go unnoticed. “There can be subtle changes in the intertidal zone that we will never see unless we are paying attention in a systematic and sustained way,” said Schoodic Institute Director of Marine Ecology Hannah Webber, who supervised Letourneau and Brumbaugh this summer. “Citizen science helps us because we can have more people on the ground, more people paying attention, and more people submitting systematic data.”

The ecology assistants sought to develop methods that could be replicated year after year to meet the need for long-term observation. Their first step was to identify the focus of their monitoring protocols. Letourneau and Brumbaugh selected two indicators of intertidal zone health that were understudied and could be assessed by citizen scientists with limited time and resources: the abundance of sea stars and the use of the ecosystem by coastal birds. These vital signs are two of many identified by Hannah Mittelstaedt, a former postdoctoral fellow at Schoodic Institute, based on community-wide discussions between scientists, managers, and people who make their living in the intertidal zone.

Species in Decline

Sea stars are a keystone species, meaning their presence significantly influences the abundance and distribution of other species, such as mussels, a primary prey item.

NPS/Nina Foster

Several coastal bird populations, many of which forage in the intertidal zone, are also in decline. Shorebirds in the United States have lost a third of their population over the last four decades. As their numbers dwindle, so too does their role in a healthy intertidal ecosystem.

NPS/Jalen Winstanley

“Sea stars are understudied in the North Atlantic, and while I started monitoring Acadia’s sea star populations in 2021, there are still so many more questions to explore,” explained Giakoumis. “The data from these citizen science surveys will help to shed light on these species’ habitat preferences, current population sizes, and the impacts of disease in this region.”

The Joys and Challenges of Protocol Design

A successful citizen science project prioritizes scientific validity, user experience, and relevance. It involves the public in an accessible and engaging research process that both creates new knowledge and teaches the processes of science.Brumbaugh and Letourneau kept these principles in mind while designing their own protocols. Inevitably, obstacles arose along the way. “It was challenging to balance making the protocol accessible for people with no research experience while making sure that the data they’re collecting is still valuable,” Brumbaugh reflected.

In consultation with researchers at Schoodic Institute and Acadia, Letourneau and Brumbaugh selected six groups of birds that Earthwatch volunteers could learn to identify regardless of their background. They include easy-to-identify species, such as common eiders (Somateria mollissima) and black guillemots (Cepphus grylle), and a group of similar shorebirds that run along the water’s edge but are difficult to identify to the species level. By including researchers and managers in this design step, the ecology assistants ensured that observations would be valuable to them.

Practice Makes Progress

Before working with Earthwatch volunteers, Letourneau and Brumbaugh piloted their protocols with fellow interns at Schoodic Institute, including me. Equipped with data sheets, binoculars, and laser rangefinders, we drove to a scenic overlook near Blueberry Hill to survey the intertidal zone for coastal birds.

Schoodic Institute/Trevor Grandin

“Gull group one is foraging on algae, and cormorant two is alert on a rock,” a colleague relayed to me, her eyes glued to binoculars while I scribbled our findings on a data sheet.

We tracked not just the species in front of us, but also those above, writing frantically to record every observation before the next minute arrived. Our stress was clear to Brumbaugh and Letourneau, who watched us with as much attention as we devoted to the birds.

That same week, we walked the shoreline in search of sea stars, algae, and other marine creatures according to another standardized protocol. In the end, Letourneau and Brumbaugh changed their protocols a bit, based on our various successes and failures. The goal is a set of procedures that yield accurate data and don’t frustrate the volunteers. Once revised, the protocols were finally ready for the Earthwatch volunteers.

Back at Frazer Point…

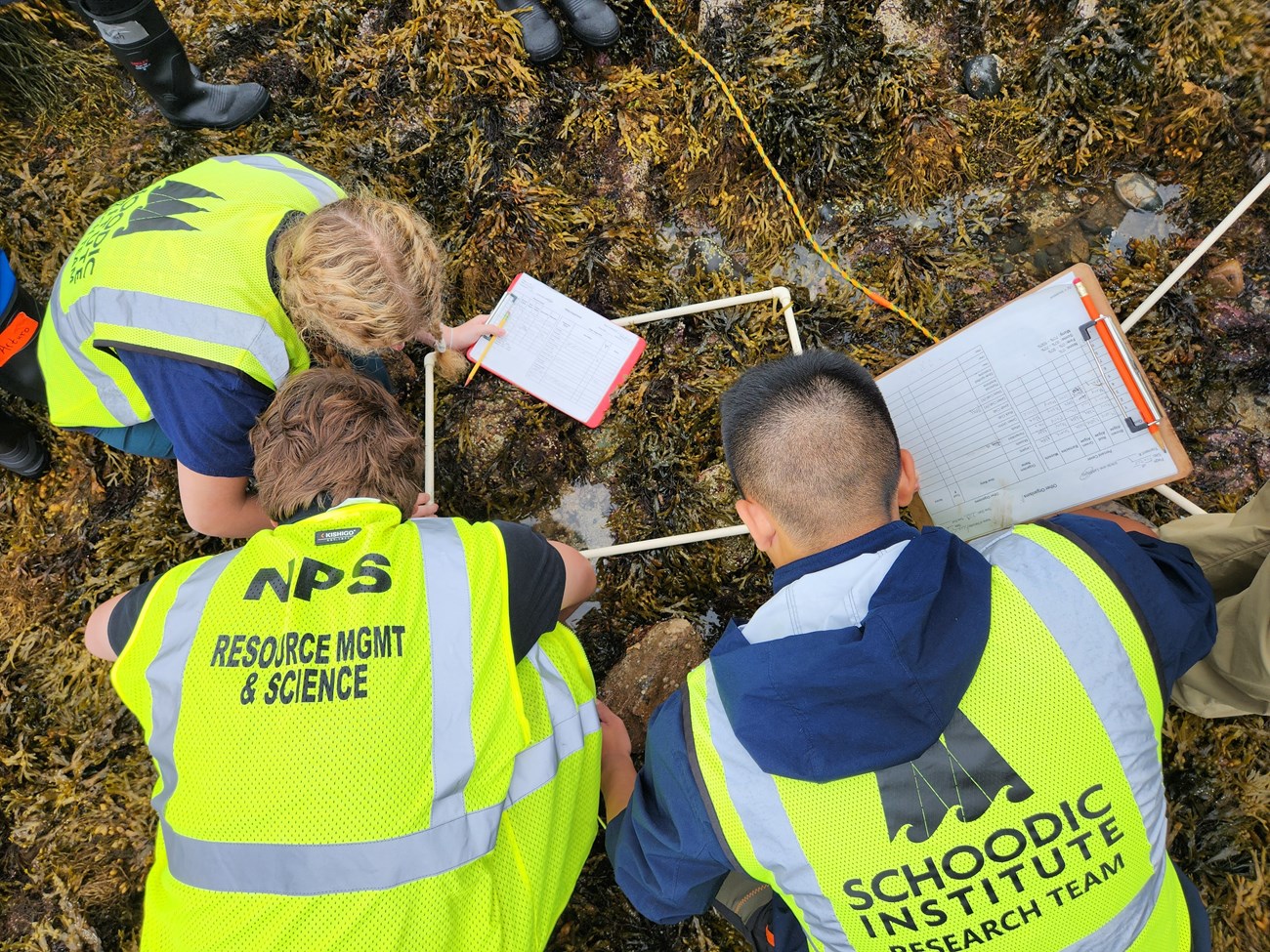

“This is stressful,” Brumbaugh whispered to me as the Earthwatch team began their search for sea stars and other intertidal organisms. She and Letourneau roamed from one group to the next to ensure the protocol was being followed correctly and to gauge whether participants were enjoying the process.

Schoodic Institute/Shannon O’Brien

Despite discovering a trove of marine creatures, volunteers were disappointed to find zero sea stars in their survey areas. As the group gathered to discuss their observations, a sharp-eyed volunteer spoke the magic words: “Is that a sea star?”

She had spotted a northern blood star (Henricia sanguinolenta) clinging to a small rock near the low tide line. Deep red in color and about three centimeters wide, the blood star exhibited no signs of sea star wasting syndrome. Just a few feet from where it was found, however, another volunteer identified a common sea star (Asterias rubens) with early signs that it was wasting away. The individual had lost one of its legs and was starting to become soft — a sobering reminder of sea star vulnerability in the North Atlantic.

Schoodic Institute/Shannon O’Brien

The following day, the Earthwatch team performed coastal bird surveys. The teens had no difficulty recognizing different birds, identifying their behaviors, and recording the data.

Back in the classroom, volunteers completed the final step of adding their observations to a database. That task provided an opportunity to reflect.

“I loved the hands-on learning aspect of it all,” said an Earthwatch staff member who facilitated the trip. “It’s different seeing it in real life compared to seeing it on a PowerPoint slide.”

Earthwatch volunteers benefitted from the experience just as much as the researchers and park managers who will use the data they collected. By engaging in multiple steps of the research process, they developed technical skills in species identification, scientific tools like laser rangefinders, and data management. Volunteers also expressed an appreciation for the time in nature and for the opportunity to learn about a new and unfamiliar ecosystem.

In just nine weeks, Brumbaugh and Letourneau developed protocols that make studying the vital signs of the Schoodic Peninsula’s ever-changing intertidal zone accessible to citizen scientists. These surveys will contribute crucial scientific data that inform the research of Giakoumis, Webber, and other professional scientists as well as the resource management approaches of Acadia National Park.

“It was so rewarding to design programs that facilitate connections between the public and the intertidal zone,” said Letourneau. “I hope that these protocols are used and refined for years to come, allowing citizen scientists to gather valuable data for research at Acadia and beyond.”

Written by Nina Foster, a 2024 Scientists in Parks intern at Acadia National Park. Nina is exploring her professional interests in writing about people, places, science, and history.