Last updated: April 7, 2025

Article

Evolving Cultural Landscapes through the Lens of the National Historic Preservation Act, 1966-2020

National Center for Preservation Technology and Training

This presentation, transcript, and video are of the Texas Cultural Landscape Symposium, February 23-26, Waco, TX. Watch a non-audio described version of this presentation on YouTube.

National Park Service

Nancy Brown: All right, so when I sent in the concept for this presentation, I had no idea Susan Dolan was speaking in front of me, and that we were going to cover some of the same ground. I am coming at it from a little bit different angle, so bear with us. Hopefully it's informative.

In 1966, a little over 50 years ago, the National Historic Preservation Act, or the NHPA, was written into law. That law did not specifically mention cultural landscapes, yet they are incorporated into preservation under the law.

This presentation is to take stock of what the act says and how it has evolved over more than half a century with regards to cultural landscapes and their changing role and their protection.

This is not meant to be a comprehensive review of all the possible changes that are affecting cultural landscapes during this time. It's based on my perception and my perspective as a historical landscape architect and former employee of the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (ACHP). That is the micro agency of the federal government with about 40 employees that oversees the NHPA and advises the President and Congress on preservation issues in the U.S. I was its first and only landscape architect by the way.

Before retiring from the ACHP in 2018, my work first focused on a variety of federal agencies, and later I became the ACHP liaison to the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). Recently I've been interviewing professionals working in both public and private practice around the country to get their recent experiences with addressing cultural landscapes under the NHPA. At the end of this presentation, I hope you will share your observations on the changing role of cultural landscapes and where you believe that preservation may be headed.

To understand how we got here, let's look back for a minute at America's history. This country has always been about progress and building anew, making things bigger and better with little concern for preservation, especially in the early years of the country. There really was no strong respect for things that were old.

By the early 20th century, at places like Mesa Verde, the removal of artifacts and defacement of archaeological sites had become common. As a result, President Theodore Roosevelt signed the Antiquities Act in 1906 to protect archaeological sites and ruins and other historic sites located on public lands. It allowed the president to create national monuments also.

Nancy Brown, Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (Retired)

In 1916, the National Park Service was created within the Department of the Interior. It wasn't until 1933 that President Franklin Roosevelt consolidated all national parks, military parks, monuments, cemeteries, and memorials in the National Park system.

In 1935, President Franklin Roosevelt signed the National Historic Sites Act into law, nearly 30 years after the Antiquities Act. It stated, "It is a national policy to preserve for public use, historic sites, buildings and objects of national significance for the inspiration and benefit of the people of the United States." It called for the creation of a national survey of historic sites and buildings to be completed within five years.

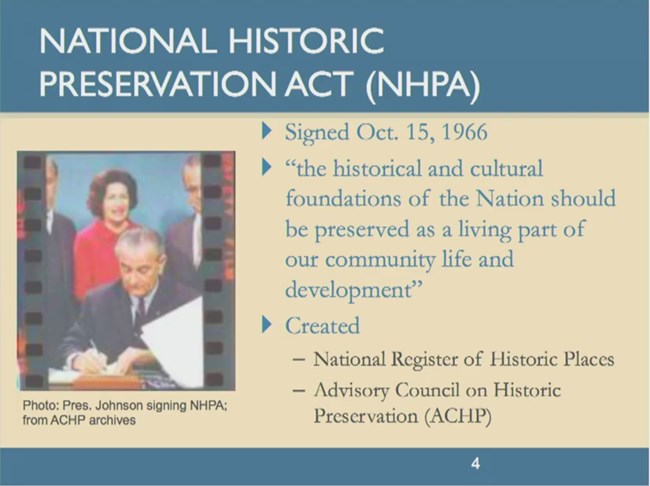

In response to the new interest in preservation, President Lyndon Johnson signed the National Historic Preservation Act or NHPA into law in 1966, 31 years after the National Historic Sites Act. The NHPA says, "The historical and cultural foundations of the nation should be preserved as a living part of our community life and development." It acknowledges that much of the work will have to be done by private agencies and individuals but calls on the federal government to accelerate their historic preservation programs and to, "Provide leadership in the preservation of the prehistoric and historic resources of the United States." And thus, the federal government was launched into becoming an active partner in historic preservation.

But World War II broke out and little was accomplished in terms of that survey. After the war, development exploded, construction boomed on the interstate highway system, the building of dams and suburbs. In the cities, urban renewal was ramping up. These government programs made many Americans aware of what they were losing to development, and for the first time brought together a broad constituency for historic preservation with a focus on saving rural America from the bulldozer.

Nancy Brown, Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (Retired)

The NHPA led to the creation of the National Register of Historic Places, and for the first time locally significant sites could be listed and included in the register. It created the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, my former agency, to oversee preservation and law and to advise the President and Congress, and it encouraged state and local government historic preservation programs through matching grants.

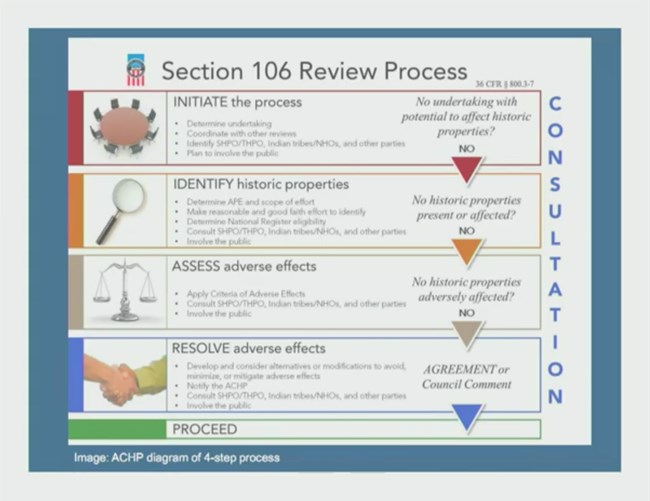

One section of the NHPA, Section 106, charges the ACHP with overseeing the process for how federal agencies will actually take historic properties into account in their decisions. In 1972 the ACHP wrote the regulations that we call the Section 106 process, the four step process illustrated here calls on federal agencies to initiate the process by identifying consulting parties who might have an interest, identifying historic properties and evaluating them to see if they are eligible for the National Register, then assessing any effects to historic properties that are actually eligible for the National Register and finally resolving those adverse effects. The four steps are done in consultation with parties that have an interest in the project or in the effected historic properties and there is no guarantee that historic properties will be preserved at the end of this process.

Now, I'm going to let Greg (Smith), as the next speaker, cover the National Register, but I just want to call out again that it is the term sites and districts that were listed in the National Register information that allow us to think about cultural landscapes.

Early landscape preservation efforts began in the 1800s with citizen groups. You probably all know about the Mount Vernon Ladies Association and their efforts to save Mount Vernon. They were established in 1853. But from the very beginning, they were very interested in not just preserving the mansion but the gardens, the fields, the views and the setting around it.

In 1928, Colonial Williamsburg began with a reconstruction and restoration program, and of course many historic cultural landscapes were adversely affected by the post-World War II development, and so landscapes were part of the widespread concerns about saving rural America. This led to a number of landscape preservation groups being founded in the 1970s and 1980s, like the Alliance for Historic Landscape Preservation and the National Association for Olmsted Parks. The Alliance is meeting in Natchitoches, Louisiana at the beginning of April (postponed until Spring 2021).

In 1980, the National Preservation Institute, a nonprofit that provides training on preservation was also founded. They are offering a two-day cultural landscape preservation workshop in October in Santa Fe, and the one-day advanced course, and I'm going to be teaching those.

NPS responded, as we just learned from Susan, with a variety of guidance on cultural landscapes. In the 1980s and 1990s in particular, the National Park Service published the National Register bulletins on the rural historic landscapes, traditional cultural properties, or TCPS, battlefields, cemeteries and mining districts, and then in the 2000s, they published one on suburbs.

In 1994, the agency came out with Preservation Brief 36: Protecting Cultural Landscapes. In 1996, the Secretary of Interior Standards that included the cultural landscape guidelines as Susan mentioned. In 1998, the Cultural Landscape Report, A Guide to Cultural Landscape Reports, and again, looking back at the law from 1966 it was about 30 years before these publications were available. In the middle of all of this, in 1992, we have a worldwide focus on cultural landscapes. They are recognized by the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

Shortly after that the ACHP revised their regulations regarding Section 106 to require consultation with Indian tribes and native Hawaiian organizations and the consideration of properties of religious and cultural significance to those groups. These revisions also noted the special expertise held by Native Americans and Native Hawaiians to assess the eligibility of these properties of significance to them for the National Register. The regulations were also revised in 2004, but that's not relevant to the discussion today. I would argue that the addition of tribal and Native Hawaiian consultation and identification of historic sites of significance to them, in the 106 process had a huge effect on bringing cultural landscapes into the discussion.

It was my experience that tribes and Native Hawaiian organizations generally bring a more holistic approach to the discussion of resources. For them, there's no sharp distinction between natural resources and cultural resources. Consultation with Native Americans and Native Hawaiians pushed many agencies to think more about landscapes and to think about them more holistically. That benefited us all who were working on cultural landscapes, discussing character, defining features like vegetation, water features, and natural systems no longer was so difficult

As federal agencies became more comfortable with the melding of natural and cultural resources, there was a steady growth in not only the acceptance of cultural landscapes as eligible for the National Register, but also in the scale of some of those landscapes. For example, Bighorn Medicine Wheel in Wyoming, a prehistoric archaeological site that was nominated in 1969, originally for only the wheel itself as part of a small 40 acre plot. The U.S. Forest Service is now managing the entire Medicine Mountain as a cultural landscape. And in 2011, the boundary was expanded to over 4,000 acres, including many more of the features of significance to the Northern Plains tribes that value this area. In 1978, the Topock Maze, a sacred site to several tribes on the Colorado River, was listed on the Register as a 33-acre geoglyph. Through consultations around 2009, that was enlarged to about 1700 acres.

There's also a broader understanding of what constitutes a cultural landscape. In 2014, the Green River drift was added to the National Register for a 58 mile trail used for moving cattle to higher summer grazing pastures since the 1890s, making it the oldest continuously used stock drive in the state of Wyoming.

A push for renewable energy from the 2005 Energy Policy Act brought cultural landscapes to the foreground of the Section 106 discussions in ways that I couldn't have anticipated. These massive energy projects were being proposed to meet the goal of 10,000 megawatts of non-hydro renewable energy that was to be developed on BLM land, Bureau of Land Management land, by 2015. Other agencies and departments like Department of Defense had their own renewable energy goals.

Nancy Brown, Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (Retired)

For solar power to make one megawatt of energy, a project needs a minimum of five acres. A small solar project of 250 megawatts needed 1250 acres or approximately two square miles of land. Even with the extensive land area that BLM manages, there are rarely large tracks that don't include some kind of potential cultural landscape. It's all been traveled through, lived on, mined, ranched or manipulated in some way. After the energy development came, there was a need to move that energy to the urban centers where the consumers were located.

So next came proposals to build transmission lines on federally managed land, some 1000 miles long. In the West, they wanted to run them through the same narrow valleys where there were emigrant trails, historic railroads, and early highways. Conflicts with historic landscapes were rife in the Section 106 consultations.

Consultations on early projects really struggled with cultural landscapes and especially with tribal cultural landscapes, but there was steady development and especially in visual effects, methodologies which were developed for one project and then improved on the next and the next and the next. It didn't exactly get easy, but it got easier.

Over the last 15 years, there were enough government efforts affecting cultural landscapes that it would be challenging to try to list them all here. Many individual agencies have broken new ground in cultural landscapes. NPS has documented the indigenous cultural landscapes of the Chesapeake Bay area. The National Register has been revising and updating Bulletin 38 on traditional cultural properties and ran the National Register Landscape Initiative, a terrific series of webinars on different landscape types, which was to form the basis for updated landscape guidance.

Unfortunately, both of these guidance efforts have remained as draft for now. The Advisory Council developed written guidance on tribal cultural landscapes, offered a webinar on cultural landscapes in the Section 106 process and included landscapes in its Section 106 success stories.

The Bureau of Energy Management, BOEM, explored underwater landscapes and there was a collaborative effort by seven agencies to provide coordinated guidance on visual resources, but that too has remained in draft form.

Nancy Brown, Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (Retired)

And of course, I don't want to overlook the many state efforts. Many SHPOs and state preservation organizations have been hosting landscape conferences just like this one, providing in-state training and also documenting important landscapes in their States.

In 2016, for the 50th anniversary of the NHPA, I evaluated where we were with cultural landscapes. I saw a need for updated cultural landscape guidance. I saw problems with reduced staff and stagnant or declining funding, but I was still optimistic about the role of cultural landscapes in historic preservation as we moved into the next 50 years of the NHPA this year to gain insights into how cultural landscapes are faring, I've been interviewing people who are working in cultural landscapes. I've talked to Advisory Council, National Register and SHPO staff, NPS, and BLM cultural resource managers, tribal cultural resource staff, contractors doing landscape work and a professor teaching both landscape architecture and preservation. They've provided an interesting, although admittedly limited snapshot into the field today.

The challenges that they identified were not uncommon. Funding remains a problem. Federal agencies have fewer preservation professionals including historical landscape architects. Due to the cost of cultural landscape reports, they're often not done as a whole document. Parts may be done independently or included in a historic structures report.

Doing a National Register nomination is expensive and difficult for an area like a landscape, so in fact relatively few are listed or determined eligible and sometimes when doing Section 106 only the properties that are already listed or determined eligible are being considered. Not everyone is out there looking for new landscapes that may be eligible. There are new mandates claiming exemption from NHPA, such as building the wall along the us Mexico border. Agency procedures limiting time and effort spent on compliance and the proposed changes to the National Environmental Policy Act or NEPA are all affecting how compliance on cultural landscapes is done.

Concerns were expressed to me regarding the National Register rule changes that were proposed last April, that if approved would allow federal agencies to object to National Register listings and ownership votes would be done by the percentage of property an individual owns instead of each owner having one vote as is now done.

It was noted that SHPO staff varies in support for an understanding of cultural landscapes. While some staff are very well prepared, not all have the skills or knowledge to address landscapes effectively. One interviewee wished for SHPOs to be more of a backstop regarding cultural landscapes so that federal cultural resource staff weren't alone in raising concerns about these properties.

Tribal representatives were concerned that in dealing with landscapes, federal agencies often want to cut off the landscape at the boundary of the federal agency property instead of really looking at the whole cultural landscape regardless of ownership.

And there are areas where we're making good progress. When asked whether they thought identification and consideration of cultural landscapes in Section 106 was generally increasing, decreasing, or staying about the same, a majority of the interviewees said it was increasing at least marginally.

Some felt there was a growing awareness of cultural landscapes. When asked what was facilitating the growing awareness of landscapes, several noted that younger hires arrive with some understanding of and exposure to landscapes. Changes in technology such as using GIS and modeling for large areas are helping to identify new resources, especially when there is effective ground-truthing of the model after it's run. And frankly, I think the passage of time is making everyone more aware of cultural landscapes.

And finally, in the past year, the Advisory Council released information clarifying direct and indirect effect. Interviewees noted that this was really helpful because it's a particularly thorny area when consulting on landscapes.

Nancy Brown, Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (Retired)

In 2016 for the 50th anniversary, I was very optimistic about the role of cultural landscapes as we moved into the next 50 years. I'd seen a lot of progress in the recognition of landscapes. Many of the major developments within the Section 106 process leading up to 2016, addressed the question of how to deal with landscapes and especially tribal cultural landscapes.

As a resource, I felt they were no longer being ignored. Looking over the notes from the interviews, I'm not quite as optimistic today. While we are still moving forward on cultural landscapes, there seem to be quite a few ways that progress has slowed or at times even stalled. But what do you think? What does your experience and your insight tell you about the future of cultural landscapes? I'm hoping that we can take some time to discuss this and I look forward to your questions and your comments. Thank you.

National Park Service

Questions and Answers

Debbie Smith: We have time for a few questions, or comments.

Ryan Perkins: Hello. Susan [Dolan] I may have you jump up as well. This question is for both of you. My name is Ryan Perkins, I'm from the city of San Marcos. I serve on the Historic Preservation Commission for the city and have been there for about eight generations, so it's a special place. I live in an area that is one of the oldest inhabited spots in North America and probably on the planet, in a site that a lot of the indigenous people consider to be the beginning of creation or Eden.

It's a very built on environment for millennia, it seems like. How do we move forward in today's age with climate crisis, with Section 106 processes, with local, state and federal guidance and guidelines for historic preservation, especially in the context of historic districts and neighborhoods. There's a lot of push, especially in central Texas, to be a bit more sustainable with water and flood control. So there's a lot of recommendations for xeriscaping and different types of landscaping.

I just didn't know if there was any sort of question in there about how we kind of move forward just from a local micro … district by district, neighborhood by neighborhood, with cultural landscapes and what you're talking about. Thanks.

Nancy Brown: Yeah. I'll just put a caveat. I sort of assume a general knowledge of this, but I should have been explicit. The Section 106 process only applies if you're on federal land, you're using federal dollars, or you're getting a federal license. Okay? So, if you and your community are working on something that doesn't meet one of those three criteria, then 106 isn't part of the way forward.

Susan Dolan: We're fortunate in the National Park Service to have a whole team of staff that help people outside of the National Park Service preserve historic places. And I'm not one of those, but I can relay what I know, that National Register listing, recognizing the significance, integrity of cultural landscapes on the Register is just the point of beginning of being able to protect what we care about.

As Nancy mentioned, Section 106, listing on the Register doesn't guarantee preservation by any means. The way the National Preservation Act was set up was to form a sort of nationwide community of preservation ethic and practice whereby preservation really happens on the local level, that where the rubber meets the road is in planning at the local level.

So, at San Marcos in your community, the tools that you can arm yourselves with are National Register listing or research about history and significance and integrity on the ground. But all of those things need to end up informing a preservation ordinance in the community that is enforceable on the ground in planning and design efforts.

And so, some of the greatest successes that communities are having around the nation with preservation is where they have adopted a preservation ordinance that identifies what is significant, what is precious to preserve in this community, and the better ones aren't just like the exterior facades of buildings and setbacks, but more about the patterns on the ground. Like we were hearing yesterday about the community in San Antonio where there would be numerous buildings on a lot, that that was a historically significant pattern. So, trying to translate this knowledge into practice for an ordinance is very important, but that even alone is not enough to have an ordinance that it still takes activism. It still takes the voices of people to hold the feet to the fire of those people responsible for enforcing ordinances, in other words never ever stops. The way forward, you have to be armed with the knowledge and the documentation has to be applied to a practical enforceable regulation and then we still need the community and people to step up and express their care to ensure these things get enforced.

Nancy Brown: Yeah. I would just encourage you, if you haven't already, to do the kind of documentation that was in the bootcamp on Sunday or the NPI sessions teach. And also keep in mind that when you get federal money for flood issues, all of a sudden 106 does kick in. So, the documentation that you have is going to be critical at that point. And the more you have, and the more discussion you've had with your SHPO about whether or not it meets the criteria for listing on the register, gives you a stronger voice at the table when the time comes. Thank you.

National Park Service

Speaker Biography

Nancy Brown, FASLA is a historical landscape architect. She has experience with National Park Service, Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation, University of Virginia, and the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation; specialist in cultural landscapes and Section 106.