Last updated: March 12, 2024

Article

The Enslaved Community of L’Hermitage

The 1790s was a time of social upheaval. The American and French Revolutions inspired civil unrest around the world. Enslaved populations partook in this revolutionary spirit, especially in the Caribbean, where enslavers dealt with uprisings, rebellions, and bloodshed. Several French enslavers from Saint-Domingue could not withstand the violence any longer and emigrated to the United States. Maryland became a major destination for French refugees, who frequently arrived with their enslaved individuals.

Vincendière Family and Slavery

The newcomers stood out in Frederick County in many ways. The French Catholic Vincendière family did not fit in with the predominantly English and German Protestant community. On top of that, they were familiar with a large, Caribbean-style plantation system that instituted slavery on a scale not previously seen by their neighbors.

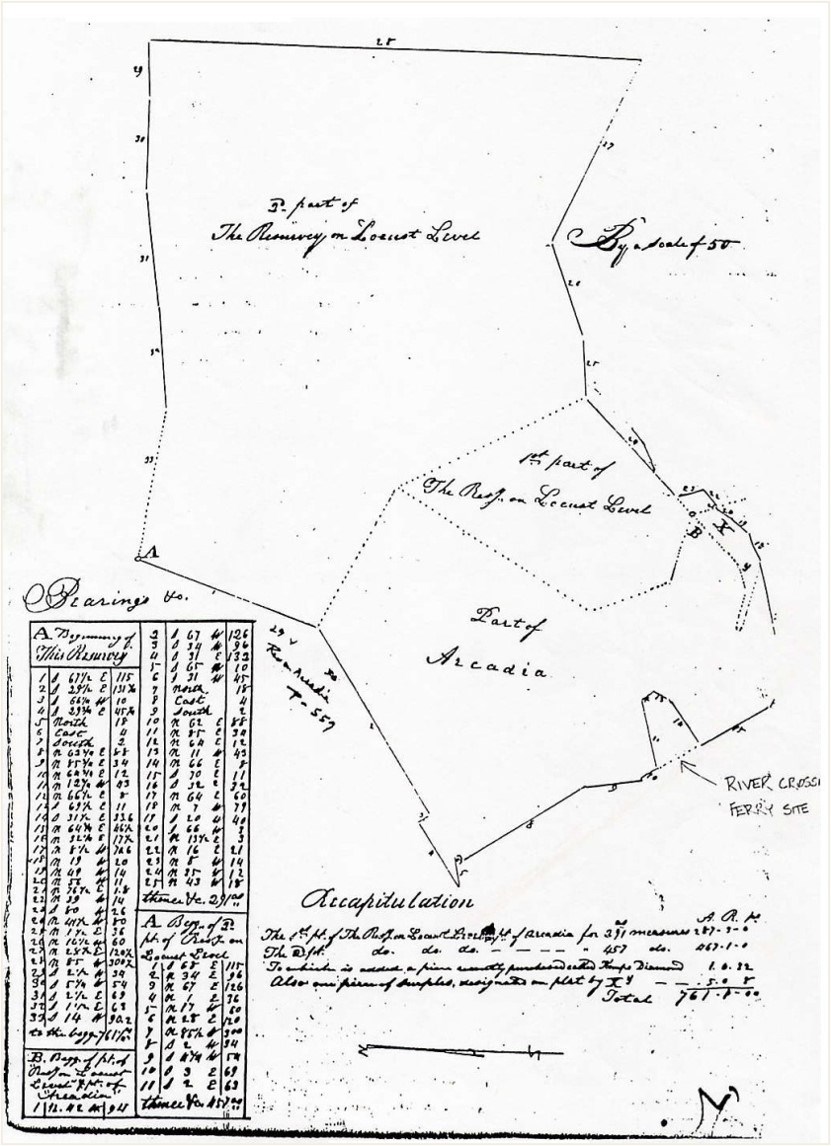

Frederick County farmers mostly relied on the cultivation of small grains rather than staple crops like sugar or tobacco, enslaving smaller numbers of Africans and African Americans. The Vincendière family acquired land that eventually became a 748-acre plantation called L’Hermitage, deviating from the smaller lots that were the norm for the area.

For the French Carribbeans, owning a large, enslaved population was deemed not only necessary for economic productivity, but an expression of wealth and power. By 1800, the Vincendières enslaved ninety people at L’Hermitage. Coming from Saint-Domingue, a colony widely regarded as having one of the most brutal and extreme systems of slavery, the family inflicted harsh beatings and severe punishments on the many people they enslaved.

The enslaved village constituted a new community in Maryland, merging with the local culture while navigating political and economic conflicts played out on a global scale. Historians gleaned the enslaved peoples’ identities from tax assessments, deeds of manumission (emancipation), and court records, reminding us these were real people that existed in time and space.

Archeology of the Enslaved

Archeologists investigated six individual dwelling houses from the late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century enslaved village of L’Hermitage. The enslaved residents constructed buildings using logs supported by stone piers and external brick chimneys. In the village, a metal detector survey uncovered a large, dense domestic deposit composed primarily of architectural materials, personal items, and cooking and storage vessels. These personal items included things people used every day, like buckles, scissors, pocketknives, and a thimble. The survey also yielded coins, buttons, and tablewares consistent with the period of L’Hermitage occupation.

The discovery of coins in the enslaved village is evidence of their participation in the local informal economy. The enslaved had opportunities to provide goods and services in exchange for money. In the process, they established social connections, economic networks, and engaged with storekeepers and neighbors after their tasks were completed. In their scant free time, the enslaved earned money through independent activities that could have been used to purchase food and drink, eating implements or vessels, tools, cloth, and personal items.

Excavations at the village site yielded over 3,000 red paste earthenware sherds and over 2,000 white paste earthenware sherds. A few stoneware, yellowware, and porcelain sherds were also recovered, all of which solidly date to the 1794-1827 period. The presence of refined tablewares suggests the enslaved accessed more expensive ceramic types. On plantations, this usually reflects hand-me-downs from the enslavers, especially when there is a lack of obvious matching ceramic decorative patterns. However, these vessels could have been purchased with money earned outside the plantation, especially since these goods were acquired in a piecemeal fashion, one at time.

The high quantity of cow, pig, sheep, and goat bones shows that their diets closely resembled those of other enslaved communities of the Chesapeake region. They commonly ate animal knuckles and feet, probably because the Vincendières did not care for these parts. They also fished for freshwater mussels, hunted wild raccoon, and harvested walnuts.

Between 1796 and 1801, Victoire Vincendière appears in the Frederick County docket books several times as she attempted to resolve about twenty-five cases of cruelty to the enslaved brought against her. One of which was for “immercifully beating her slave Jenny” in 1797. These cases were usually dismissed, as the defendant would simply argue it was perfectly legal to beat an enslaved person.

Despite this abusive tyranny, the enslaved individuals at L’Hermitage managed to resist. Pierre Louis gained his freedom by proving in court that the Vincendière family brought him to the US illegally in 1793. The Vincendières placed several advertisements for runaway slaves in the Maryland Gazette, including one for Jerry, a 25-year-old brickmaker who escaped in 1795.

Sources

Beasley, Joy

2012 Entre Autres: Conflict and Complexity at L’Hermitage. Paper Presented at the SHA Conference in Baltimore, Maryland.

2005 Archeological Overview and Assessment and Identification and Evaluation Study of the Best Farm. Monocacy National Battlefield. Frederick, Maryland. National Capital Region. National Park Service.

Birmingham, Katherine D., and Joy Beasley

2014 Archeological Investigation of the L’Hermitage Slave Village. Monocacy National Battlefield. Frederick, Maryland. National Capital Region. National Park Service.