Last updated: August 5, 2024

Article

An Economy of Adventure: The Life of a Voyageur

Lower- and middle-class French-Canadian men journeyed the Voyageur’s Highway to satisfy the increasing European demand for beaver pelts but also to seek the promise of adventure. In the northern wilderness, they navigated obstacle after obstacle, devised rowdy romantic tunes to entertain themselves, and exchanged goods, languages, and practices with Native American peoples.

While some songs and anecdotes are preserved in firsthand sources, voyageurs’ patterns of movement and exchange can also be detected in the archeological record. Archeological projects at Voyageurs NP in the late 1970s to the present deepen understandings of the voyageurs’ lives—how they moved, shared cultures, and forged a lasting economy across an unfamiliar frontier.

Life on the Move

Fur trade in the area is reported to have begun in 1688 when independent French trader Jacques de Noyon passed the winter at Rainy Lake. Since French maps demonstrate knowledge of the major travel routes coming from and entering the Rainy Lake hub before 1700, middleman exchanges likely preceded direct French contact by several decades.The first decades of the French regime in the Minnesota area are barely documented, though the high volume and detail of records from 1713 through the 1750s confirms a swell in French activity. By 1717, France had initiated expeditions from Montreal to establish formal trading posts. This activity peaked between 1731 and 1736 due to the strong leadership at Fort St. Pierre, a strategic Rainy Lake location less than 10 miles from the western edge of Voyageurs National Park.

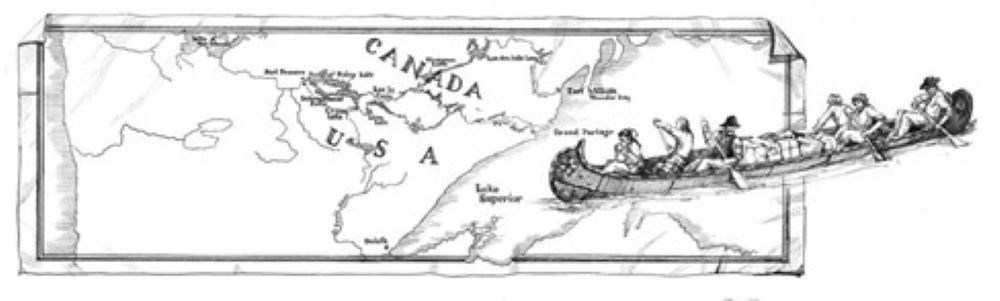

Men set out for these posts when the lakes thawed at the beginning of the season. Their canoes, designed and often built by Ojibwe from birch bark, cedar, spruce resin, and/or spruce roots, each weighed about 300 pounds and were about 25 ft long and 4 ft wide. Delays in travel were frequent because canoes required consistent upkeep. Bad weather could also waylay and imperil crews, and physical discomforts like mosquitoes and fatigue were common. Yet most voyageurs enjoyed their profession and made the best out of even the toughest of situations.

Being a voyageur was not an independent undertaking. Crews of four to six managed canoes that traveled in groups known as brigades. Each man assumed a different role, such as the avant, who guided the canoe from the front, and the commis, a clerk who usually came from a higher social background.

Along the long route, voyageurs also bonded with Native American peoples, including the Cree, Assiniboine, Ojibwe, and Sioux. The men were primarily concerned with exchanging European goods for furs, skins, and other marketable animal products. Second came the “provisioning trade,” in which voyageurs acquired food and other supplies from Native American peoples. In one case, trader Jonathan Carver credits a group of Ojibwe for saving his party from starvation in 1767. All posts, to some extent, relied on Native American peoples for dried fish, animal fat, berries, and more essentials.

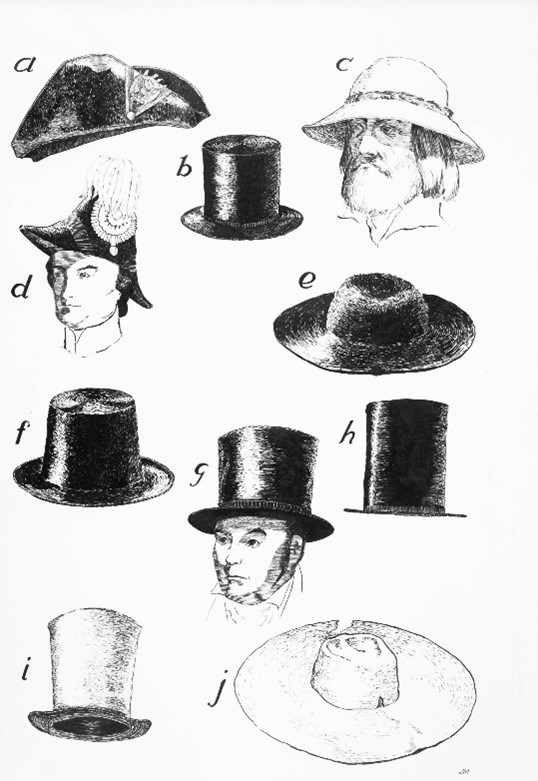

Life in the Voyageurs NP region was compiled by fur trade scholar and historian Grace Lee Nute’s publications from the 1940s and 1950s. Nute notes voyageurs mixing cultural attire by wearing French striped cotton shirts with moccasins. French-Canadian men learned to adopt the Ojibwe diet and semi-nomadic way of life, and Native American individuals often celebrated New Year’s alongside the traders. Exchange was not limited to physical goods but encompassed enduring ways of life.

Tracing What They Left Behind

Modern archeologists looked for evidence of temporary camps, strategically placed at mouths of rivers, where these lively interactions between European American traders and Native American peoples may have occurred. There are at least 23 archeological sites at Voyageurs NP with elements related to the fur trade.

Many artifacts are also in private collections because local citizens and tourists extensively removed artifacts from the exposed beaches in and around the reservoir lakes, both before and after such activity became illegal.

The Robert Bolstad Collection at the Koochiching Museums features Jesuit rings, brass rings that grew in secular popularity in the fur trade after the 1700s. Another private collection contains cobalt-blue and white man-in-the-moon beads, which are associated with French colonial presence, specifically between 1700 and 1750.

The Limits of the Past

Although wide-ranging, private and National Park Service archeological collections do not complete the full picture of the fur trade era. Many trade goods were organic objects or consumable commodities, whereas the surviving ones are mainly metal, glass, and stone. Private collections also present biases. Collectors cannot see or may not recognize all artifacts, and they tend to favor metal artifacts and brightly colored beads, underrepresenting glassware, nails, and building hardware.In many cases, it is already too late to systematically document private collections. Many of the original collectors have passed away and their collections have been scattered. Even intact collections are nearly impossible to place because details of where, how, and when the artifacts were found is lost. Additionally, the construction of dams in the early 1900s reshaped the area’s shorelines and islands and moved artifacts from their contexts.

Despite uncertainty in the archeological record, the park’s environment—its rocky lakeshores, forested uplands, and labyrinthine waterways—still bears a strong resemblance to the landscape familiar to voyageurs. The voyageurs’ determined and adventurous spirits will always remain at home in Voyageurs NP as archeology continues to unravel their legacies.

Resources

Birk, Douglas A., and Jeffrey J. Richner (editors). From things left behind: a study of selected fur trade sites and artifacts, Voyageurs National Park and environs, 2001-2002, 2004. Midwest Archeological Center Technical Report. Vol 84. USDI, National Park Service, Midwest Archeological Center, Lincoln, Nebraska.Nute, Grace Lee. “The Voyageur.” Minnesota History, vol. 6, no. 2, 1925, pp. 155–67.

Richner, Jeffrey J. Expressions of the past: Archeological research at Voyageurs National Park, 2008. Midwest Archeological Center Technical Report. Vol. 104. USDI, National Park Service, Midwest Archeological Center, Lincoln, Nebraska.

Special History: The Environment and the Fur Trade Experience in Voyageurs National Park, 1730-1870. National Park Service.

Voyageurs of the Fur Trade. National Park Service