Last updated: July 31, 2020

Article

Earthen Architecture - FAQs

Left image

East side of church, circa 1870s

Right image

East side of church, 2019

Credit: credit John Vantland

How do adobes deteriorate?

Earthen architecture – such as adobe buildings at Tumacácori – is particularly prone to erosion. Water droplets or wind-driven aggregates bump off particles making up adobes. While eroding adobes look similar to ‘melting,’ like an ice cream bar, describing adobes as ‘melting’ is incorrect. Clay and sand that make up adobes do not melt unless heated above the melting temperature of both matters.

Left image

Original decorative work on exterior cemetery wall

Right image

Repair work done to mortuary chapel

How do you protect adobes?

Lime render shields the exposed adobe walls from erosion. Spanish masons and indigenous people rendered adobe walls, but due to age and weathering, the rendering on walls has detached in sections over time. Most of the lime render visible at Tumacácori is actually the work of modern-day masons and conservators. Original lime render did survive in in the cemetery, distinctly marked by incised crosses or black-and-red cluster decoration. The façade and the interior of the church also retain some original render, and even painted finishes. Protecting the original lime render in turn protects the original adobes underneath, although the fragility of the original lime render makes this task challenging and requiring further research before they are lost.

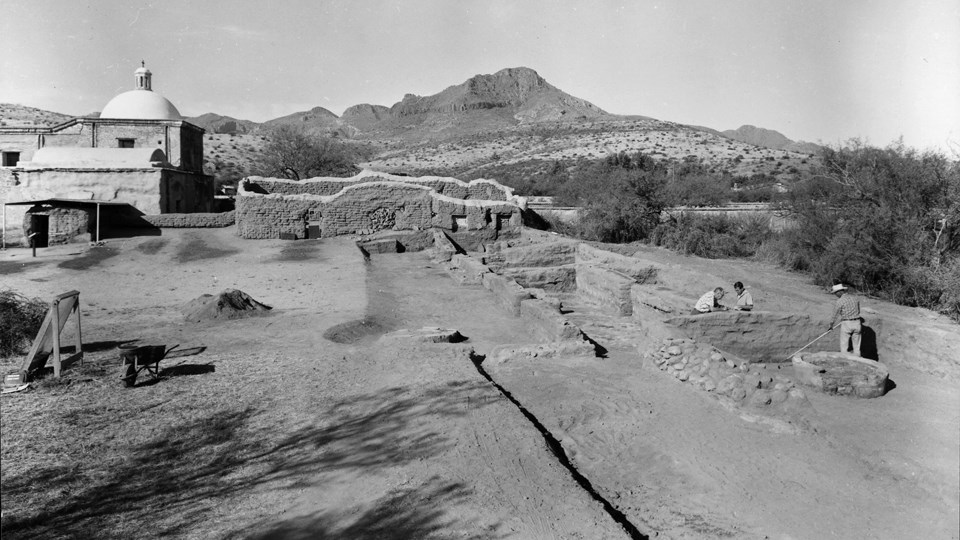

What about archeological ruins?

When the rooms east of the storeroom were excavated, a fascinating aspect of Spanish Colonial Mission life came to life, complete with a kitchen, a mill, and a metal workshop among others. They were all reburied after a heated discussion came to a standstill on how to reveal them while at the same time to preserve them. Such debate still continues to this day. Combined with above-ground building remains, the re-buried structures tell a more complete story of the scale and the extent of mission operation in the Santa Cruz Valley.

What about building a roof or using other methods?

A protective shelter, such as the one over Calabazas, limits the exposure of the earthen ruin to precipitation. However, exposed adobes continue to erode due to wind-driven rain and sand abrasion. A compromised view-shed by the shelter is the most significant negative impact to a ruin site.

Many earthen ruins, including the remains of the convento, are re-buried for protection after excavation. An underground environment is steady and stable, protecting the adobes, soil mortar, and lime render. Once buried, however, visitors cannot see them in person. Visual and written aids are available to assist the visitors in imagining how the site appeared during the historical period.

Some landscaping options do exist, such as in neighboring Tubac Presidio State Historical Park, where the footprints of the buildings are outlined with rocks.

Why not restore the mission?

Restoration is an act of individual or group interpretation to bring back a building to a point in time that may never have existed. The mission church of San José de Tumacácori was never completed and no blueprint survives. Furthermore, weathering and aging over time made it fragmented and fractured. Restoration, although tempting, distorts the history at Tumacácori.

Instead, the National Park Service treats the buildings and ruins as a document of history and abstains from making a physical (and often irreversible) interpretation on them by ‘restoring.’ Instead they are preserved in place, allowing for continued study. As a result, the ruin at Tumacácori is an excellent example of how Spanish designed and constructed earthen architecture in the desert southwest. Tumacácori has a distinction of being the first federally-protected Hispanic cultural monument in the United States.

What about making a replica?

The Visitor Center and Museum building was designed by a team of specialists from the National Park Service as a guide to understanding Spanish colonial mission architecture in Arizona and Sonora. The color scheme, architectural details, layouts and dimensions were all carefully selected and executed in order to aid the visitors in getting the sense of Spanish colonial mission, without having to restore the ruins themselves. Visitors can now study and enjoy the museum first, before walking out to the ruins.