Last updated: July 21, 2021

Article

From Asia to the Americas: Late Ice Age Colonization Corridors

NPS Photo

E. James Dixon, University of New Mexico

November 5th, 2015

Archeological evidence indicates that people first entered the North America during the last Ice Age by at least 16,000 years ago. Based on genetic and research, Northeast Asia appears to be the most probable region of origin. Researchers have advanced two primary theories about the first movement of people into to the Americas. The traditional theory postulates human migration across the Bering Land Bridge and then southward through a deglaciation corridor in western Canada. However, current research supports a maritime route along the southern coast of the Bering Land Bridge and Gulf of Alaska, and then southward along the Northwest Coast.

Transcript

Two weeks ago NPS archeologist Josh Moreno and David Gatsby talked about investigation and management of the HMS Fowey, a an 18th century British ship whose remains are located in present day Biscayne National Park. The Fowey struck a coral reef and sank in 1748 near present day Miami, Florida. An archeological investigation in 2013 documented the surviving portions of the wreck and developed a stabilization to preserve the site in situ.

Josh talked about the painstaking work that was carried out to verify the ship’s identity, to understand the wreckage that was still in place, and to map the wreck site. David talked about the equally important work to establish an agreement with the British Navy to allow the park services to continue to care for the site. I was really amazed by the level of detail that went into this kind of work and the inferences that the archeologists were able to make from the small details in the construction of this ship.

The recording of the webcast will soon be posted on the Learning and Development website where you can access this and other webcast if you were not able to listen to them live. Next Thursday Charles Meide - if you're on I hope I pronounced your name right - is going to bring us up-to-date on another research project in Florida, to locate four 16 century French galleons. The ship had been sent from France in 1655 to replenish supplies at Fort Caroline and were lost in hurricane while attempting to attack Spanish forces at the recently established Saint Augustine. If the ship had not sunk, there's a good chance Florida would have been a French colony rather than a Spanish one. Forces then marched on Fort Caroline and demolished the fort which was then undefended and executed survivors from the ship wreck and which ended France's attempts to colonize the southeast coast.

It's a really interesting story and I'm anxious to hear about these research efforts to locate the sunken ships. I'm looking forward to this talk and I hope that you are too. All of the talks will begin at 3:00 Eastern Time unless otherwise noted. Before I introduce our speaker today, I wanted to remind everyone to put their phones on mute unless asking questions. Today I am very pleased to introduce archeologist James Dixon.

Dr. Dixon received his Bachelors and Masters from the University of Alaska and his Ph.D. from Brown University. He was a Marshal Fellow for Research at the National Museum at Denmark and a professor and curator at the University of Alaska until 1993 when he became Curator of Archeology at Denver Museum of Nature and Science. In 2001, he was appointed Professor of Anthropology and Research Fellow at the Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research at the University of Colorado. Since 2007, he has served as Professor of Anthropology and Director of the Maxwell Museum of Anthropology at the University of New Mexico.

His most recent book "Arrows and Atl Atls" provides an overview of cultural development over the regions of Alaska, Russia, and Canada known today as Beringia. I can tell you it's a very good read and it synthesizes a lot of data. The maps and charts are very well done and I found them to be particularly helpful. He also put together a series of profiles and photos of arctic archeologists. That's a nice tribute to the giants who came before use and it puts faces to many names in arctic archeology. I particularly appreciated the profiles of our Russian colleagues. Unless you've met them, you very rarely see pictures of our foreign researchers. "Arrows and Atl Atls" was published by the National Park Service, by the way, so it should be available to everyone.

This year, Dr. Dixon was appointed to the National Science Foundation advisory committee and Geosciences that administers, among others, the Division of Polar Programs. He has extensive experience on in research on human colonization, high altitude and high latitude human adaptations, and early cultural development of the Americas. He will draw on that knowledge for his talk today, "From Asia to the Americas: Late Ice Age Colonization Corridors" examines recent research on the peopling of the New World including a maritime route along the western coast of North America. It look like you're on and you're ready to go. Thank you for joining us today. I'm sorry that it was little more exciting than it needed to be, Jim.

James Dixon: No problem, Karen. Thank you very much for that nice introduction. It was very kind of you. Can you hear me all right?

Karen Mudar: Yes, we can hear you fine. Thank you.

James Dixon: I'd like to start in today by providing a broad overview of the peopling of the Americas and then drill down on the Northwest coast area of North America, which in recent years has emerged as a very viable alternative hypothesis for the peopling of the Americas. Are my slides coming up and is everyone able to see the first one of the African savanna?

Karen Mudar: Yes.

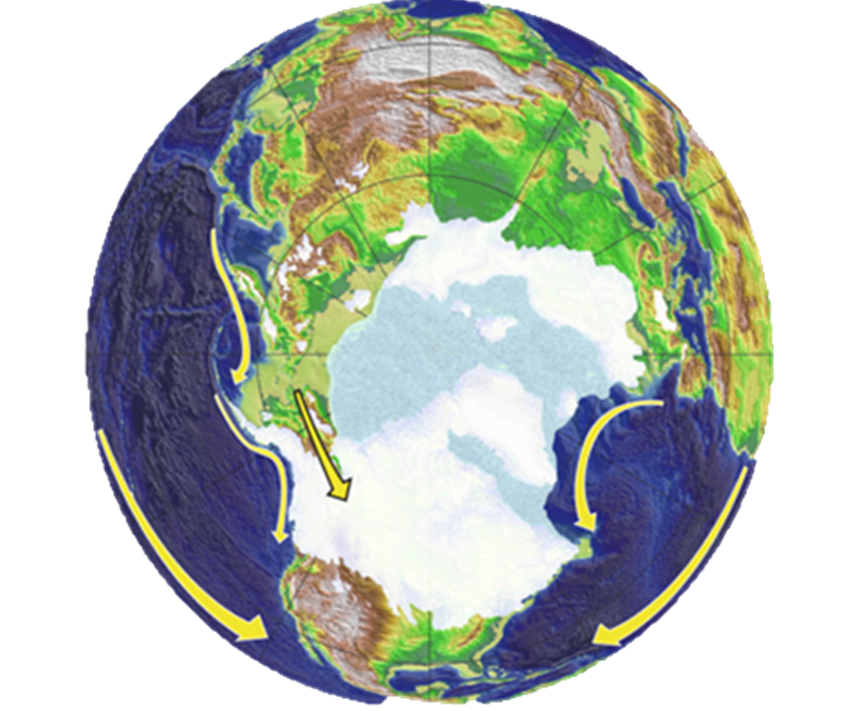

James Dixon: Very good. As all of you know, probably, and to just give a big picture here and start to drill in on the local area, humans evolved in Africa and spread from Africa out into Eurasia and, ultimately, to the Americas. When one looks at the colonization of the Americas, I think that most of the archeological evidence suggests that this occurred during the Pleistocene, during the last glacial episode in North America. If you look at it from a polar perspective which you can see in this illustration. There are really only five viable hypotheses in terms of routes to the Americas.

One, of course, is from Asia across the Bering land bridge into North America, the continental route. Another is along the southern margins of the Bering land bridge and down the west coast of the Americas. In recent years, my colleague and friend Dennis Stanford has proposed what he calls the Solutrean hypothesis. Which suggest that late Ice Age people may have been able to colonize the Americas by skirting the ice fringe, the polar ice cap, along the North Atlantic with the use of water craft and then reach the American continent that way. Finally, and these have been around for hundreds of years, transoceanic hypotheses, where people may have crossed the Atlantic, or broader expanses of the Atlantic and Pacific, to reach the Americas.

What I'd like to do today is really focus on the two routes which, I think, are most talked in North America. One is mid-continental route and another other is along the north Pacific of North America. During the height of the last glaciation about 18,000 radio carbon years ago, roughly, North America and Asia were connected by a land bridge. We call it the Bering land bridge but really it was very broad expansive of the continental shelf, more than 1,000 kilometers wide from north to south. The Bering seas, you see, are very shallow. When glaciers were at their height during the last Ice Age, sea level was lower, almost 200 meters, not quite. This exposed the broad plain stretching between northeast Asia and Alaska connecting both North America and Asia and

they were essentially one continent at that point in time. If you look at this slide you can see the lighter green area denotes the continental shelf. This is area that's all under water today as part of the Pacific and Arctic oceans. The darker green areas on the viewer's left is Chukotka, northeast Siberia, and on the right is Alaska, which is the northwestern extreme of North America. This will give you an idea of how the continents were interrelated and, of course,

the standard paradigm has been for many years, probably more than 100 years, that people first came Asia to North America via this route. As sea level rose over time, the continental shelves gradually flooded, sea level rising. Here's a sequence from the upper left to the lower right of sea level rise at the end of the last Ice Age. Beginning about 15,000 years ago you can see that sea level was about 88 meters below its present level. If you look at this slide what emerges here is a vast very complex archipelago along the southern part of the Bering land bridge. Some people have hypothesized this have been a very productive environment for marine mammals, fisheries, shell fish, and so forth. The southern coast may have been a very viable route for people to follow into the Americas. Certainly we have people in northern Japan and adjacent parts of Asia that are living on islands and appear to be maritime-adapted very early.

One hypothesis is that people would have spread along the east coast of Asia, northward along the southern margins of the Bering land bridge, through the gulf of Alaska and then south into the Americas. You can see from this depiction here this southern margin was certainly viable, both ecologically and in terms of glaciation, which I'll talk more about here as we move forward. The standard paradigm is that Ice Age hunters were in Asia hunting mammoths and so forth, crossed the Bering land bridge when sea levels were lower during the last Ice Age, then moved south, allegedly, through a hypothesized ice-free corridor into the continental United States area, areas south of the continental glaciers, where they continued hunting mammoths, large Pleistocene animals, and were the first colonists of the Americas.

However, you can see from this reconstruction of the glacial limits during the height of the last Ice Age about 18,000 years ago, that there is no ice-free corridor, there never was during the last glacial maximum. If you trace this back in the literature, it really starts back in the 1930s when geologist, W.A. Johnson, suggested that there may have been ... I haven't actually read his original publication. That's all he says. There may have been an ice-free corridor. I think he offered that to explain that fact people were south of the continental glaciers at that time. Since then, we have realized that this is not the case. There never was an ice-free corridor. As the ice melted, a deglaciation corridor appeared. If I had my preference, I would say that we should drop the term “ice-free corridor” altogether and refer to the deglaciation corridor that emerges later in time as such and not refer to it as ice-free corridor.

As people got south of the ice, there was good evidence that began to emerge in the 1930s, that humans have hunted Pleistocene fauna - mammoths. This is a photo of the famous Dent site where Clovis points and mammoth remains were first found in association. Here's a slide of the Clovis points that were actually found at the Dent site. I just love this photo of everyone excavating there because I love the way these guys were wearing their ties, hats, and their suits and they’re here in the dirt, going at it. Very formal excavations!

These original artifacts weren't fully accepted at the time because the investigators had some concerns that they might not be associated. There might be some questions of redeposition or other geologic factors that may have disturbed the site. They did not fully name it and accept it. It wasn't until the subsequent Clovis discovery that it became widely recognized as Clovis.

The idea is that people came down southward from Beringia through the ice-free corridor. Here, we have this wonderful portrayal, it's a little faded in this slide, an artist’s conception of what this migration might have looked like. When they got south of the ice, of course, they encountered a suite of Pleistocene fauna that were very similar to those that were existing in Alaska and in Asia. This was a very uniform environment and adaptive strategy for early Paleoamericans.

Here's a gratuitous slide of Clovis projectile points. However as time has gone on and we've examined this very simple and straight forward model of hunter's coming across the Bering land bridge bringing this Clovis type technology down to an ice-free corridor and then encountering the Pleistocene fauna of North America, we've realized that archeological picture is far more complex. We have a number of archeological sites in Alaska that date to about 14,000 calendar years before present. This is well before a deglaciation corridor emerges in the central continent.

The artifacts associated with these very early sites are quite different than Clovis. They are very different. They are these Eurasian microblade traditions. These are pictures of microblade cores from the Swan Point site, a very well stratified archeological site in eastern Beringia, which is now Alaska, that dates to about 14,000 years ago. You can see that this technology, this entire approach to environmental adaptation, is very different than Clovis. Clovis lack microblades. They both have blades or blade-like flakes but the bifacial technology is quite different and the microblade technology is entirely absent from Clovis. There really is a mark difference between these early eastern Beringia microblade traditions about 14,000 years ago and Clovis, that first appears south of the continental glaciers, more than 1,000 years later, almost 2,00 years later.

This is a another depiction. I should say that these illustrations from an article in Quaternary International that I published a few years ago, showing the deglaciation sequence. What is unique about these is that they both incorporate the flooding of the Bering land bridge over time along with the deglaciation of North America. You can see the relationship of the land connection between Asia and North America and the land connection between eastern Beringia, what's now Alaska and the Canadian Yukon, and the area south of the continental glaciers.

By about 16,000 calendar years ago, you can see that there's starting to form, in western Canada, a deglaciation corridor. It is certainly not open, and there's vast areas of ice still blocking access between eastern Beringia and what Alaskans would call the Lower 48. If you look at the Northwest coast of North America, you can see that the Northwest coast is ice-free by this time. This is a very important fact in looking at possible migration corridors.

You don't have to read this whole thing but just to assure you these aren't just pretty maps that Jim Dixon created on the back of an envelope or something. They're really based on a very rigorous review of glacial mapping for both Canada and United States. It's quite clear that this accurate mapping really does reveal the sequence of deglaciation and its relationships along the both the west coast of North America and the central continental areas. These are the sources that I used to compile these maps.

We're still moving forward in time. Now we're at 15,000 years ago and finally a deglaciation corridor has opened between eastern Beringia and the more southern areas of North America. You can see that deglaciation has progressed even further along the Northwest coast of North America. It has been thousands of years now that that has been open. In fact, we know now that there were refugia that were not glaciated along that coast.

The paleoecological research in the area of the ice-free corridor, or I would call the deglaciation corridor, really shows a very impoverished environment. There are no mammal bones dated from this time period at all. The pollen records are very sparse. Some scattered sedge and maybe some mosses but it's very, very impoverished. By 14,000 calendar years ago, you can see the deglaciation along the Northwest coast is extensive. In fact, to almost what it is today and yet in the central part of North America it is still very, very narrow. A very narrow corridor, biotically impoverished. These blue areas are actually pro-glacial lakes that were in the corridor area. We can see these lakes coming and going. There have been no fish remains, anything like that, found. They appear to be glacial out-wash deposits, glacially dammed lakes. A very challenging and biotically impoverished environment, not conducive for human or animal colonization until a bit later.

About 13,000 calendar years ago, you can see the interior corridors now wide. We're starting to pick first mammal remains and plant remains. By 10,300 years ago or so we have the first radio carbon years - that's about 12,500 calendar years - This is about 500 years after the previous slide we just saw. The side of Charlie Lake Cave has not only archeological remains but bison remains as well. The DNA of the analysis of the bison remains shows that the northern and southern bison have come into contact at this site by about 12,500 years ago. Probably a good date for the opening and the viability of a deglaciation corridor is about 13,000 to 12,500 years ago, somewhere in that range. If you also look at the Northwest coast, it is completely deglaciated at this point. It has been open for colonization and migration for at least about 4-5 thousand years prior to this.

This is a slide of Charlie Lake Cave, courtesy of Jonathan Driver. You can see that this is a very deeply buried stratified site. The quality of the data - and it's very well excavated - is very high and reliable. At the area of the cave we started to pick up what many people would call the northern paleoindian tradition. These basely thin concave-based projectile points. These occur in Alaska as well. It's quite clear now that we have dated these, both in Alaska, the Yukon territory of Canada, and the areas of the deglaciation corridor, that they are younger than Clovis. These are very late paleoindian types of projectile points. It's quite clear that this technology is not coming from north to south but south to north.

One of the things it means is that people actually lived south of the continental glaciers prior to the melting for this technology to spread northward to the deglaciation corridor. This actually has to be a movement of people because this area was uninhabited prior to that time. It was covered by glacial ice. This isn't diffusion or trade or something like that. It is a clear movement of people to previously unavailable territory. We just happen to have this very rare photo of two bison clades meeting at Charlie Lake Cave.

[00:26:47] I would like to go back and take another closer look at the northwest coast of North America. We're back at 16,00 years ago. If you'll take a look here, we have completely deglaciated coast line all the way from Kamchatka all along the southern coast of the Bering land bridge, along the Gulf of Alaska, all the way down the west coast of North America and providing a, what John Erlandson has referred to as the “kelp highway.” It's really a continuous biome from Asia to North America of seals, fish, a variety waterfowl, marine mammals, shellfish, that is very similar from one side of the north Pacific to the other. The idea is that people adapted to this type of ecosystem could have moved along this unoccupied coastline into the Americas thousands of years of earlier than they could of by a central route. This doesn't preclude the Solutrean hypothesis or transoceanic voyaging and so forth, but it is I think plausible, in fact probably the most plausible in my mind, hypothesis for the earliest peopling of the Americas.

[00:28:21] A little closer look at this and you can see that the shoreline at 16,000 years ago and we have large areas, particularly around the Queen Charlotte Islands, which is this area here. Along northward, Prince of Wales Island, and the continental shelf is submerged along here as well, vast areas in here along the west coast of Mitkof island and so forth. These areas were refugia during the Pleistocene and we know this because we have biological data in terms of marine mammal remains from caves. We have arctic fox; we have some terrestrial mammals. There are even caribou remains that have been recovered from Prince of Wales Island which is right here on this map, that clearly demonstrate that even during the height of the last glaciation 18,000 years ago there were pockets of refugia on this coast in which terrestrial mammals, marine mammals, fish, survived during the Pleistocene.

In fact, some of the pollen evidence, I'll show a little bit of that later, also suggest that there may have been refugia for shore pine. There may have been some trees along the coast line in pockets.

Karen Mudar: Jim, can I interrupt you for just a minute? If you want to use your computer and type during these that's fine but you need to mute your phone, so we can't hear you. Thanks.

James Dixon: I wasn't typing. Must be someone else.

Karen Mudar: Sorry. You weren't, but someone was!

James Dixon: Thank you. Where am I here? Oh, yes. This is a photo over the coast of Greenland and it will give you an idea of what some of the coastline along the northwest coast of North America may have looked like during the height of the last glaciation. There certainly were places where valley glaciers, tons of glacial ice came out to the ocean but these could have easily been skirted by the use of water craft, to the refugia on either side. This is a very close view but some of the refugia on the Northwest coast were much larger than this, supporting brown bears, caribous, and other species as well, arctic fox.

Here's a map of the Northwest coast. If you look in the upper right in this area, you'll see that the box depicts the area of the map on your screen. The red dots are various archeological and paleontological sites where we have good evidence documenting both the paleo-environmental records and the early archeological finds along the coast.

Here's a composite pollen, not diagrams, but stages of plant development along the Northwest coast. The upper part is in the northern area which is what we call Southeast Alaska. Not Southeast to you but if you're in interior Alaska it is Southeast, and British Columbia, which is immediately south along the coast. You can see that we have very good pollen records all the way back to about 13-16 thousand years in various places. This work is still in its early stages. If you look at Mitkof Island, for example, you might say the record terminates at 13,000 years ago and so it must have been glaciated at that time.

I think it’s very important, you can do the same thing for Pass Lake, Prince of Wales Island and so forth. I think it's very important to keep in mind that these sites are very landward and not out on the continental shelf or the islands further to the west. What this suggests is that these areas may have been colonized by plants a little bit later but if you went further west, you would find similar records to what we see in British Columbia or on Pleasant Island and further, seaward. The problem is that probably some of the oldest records are now under water on the continental shelf. Clearly by around 16,000 years ago, plants are well established and we certainly have terrestrial mammal records going back much earlier.

So, just to summarize, the Late Glacial Maximum archeology paleoecology along the Northwest coast and LGM here, stands for last glacial maximum. It is diachronous, which means it didn't all happen at the same time in the same place. In other words, glacial ice may have advanced a little earlier in one area, retreated a little earlier in another and so forth. It's a very complex record that's going to take many, many more years to fully understand. Glaciation reaches maximum extent between about 20-16 thousand calendar years ago and before I saw the LGM [dates], I was using 18,000 radio carbon years ago. That brackets it down into calendar years for you. The LGM ice conditions were severe but there were terrestrial plants and animals that survived in refugia along the coast and marine species, such as ring seal, survived in locally favorable marine environments. The reason we know this, is we actually have the fossil remains of the ring seals at the height of the last glaciation. These are a type of seal that live further north now in the higher arctic. It gives an idea about the ice conditions at that time.

At the end of the last glaciation sea level rose very rapidly. Here's a chart of the late Pleistocene sea level rise beginning about 16,000 years ago shortly after the LGM. You can see it's very steep and rapid. This is amazing and it's due to a number of geological factors. One is what is called a forebulge effect. As the glacial ice moved down from the Canadian Rocky Mountains seaward, moved westward flowing out of the mountains toward the ocean. It produced a great deal of weight on the land it forced what's called a forebulge. It's like if you slide your foot along the carpet, there's a bulge of carpet rises in front of your foot. It's kind of like that.

The land in front of the ice actually rose up so the extreme continental shelf of western North America was much higher than it is today. When this load of ice was released, this forebulge collapsed and sea level rose very rapidly. That's what we're seeing here in this graph. This very rapid rise of sea level in the period of just a few thousand years it rises a 160 meters. This complex geology makes it very difficult to try to identify sites both on land and on the continental shelf that might date to this time period.

Nevertheless, we've made quite a bit of progress. This is a slide shared with me by a colleague, Daryl Fedje, who has done quite a bit work in British Columbia. Immediately south of the area that I've been working in. This is K-1 cave, it's right up here in this area of the slide. He and his team have worked there. Of course they found a number of exciting discoveries. Here's a very large brown bear mandible. We're finding many of these bears in this cave, along with it the bases of two projectile points. I just wanted to take a minute to point these out. This is the base of a projectile point. It's ground a little bit on the edges. Here's the base of another one. You can see it's this kind, broad-leaf, shaped type of form.

Here's another two caves that Daryl worked Gaadu Din 1 cave. It's right here where this red circle is. Gaadu Din 2 is right here. Here's some of the excavations. Again, he discovered projectile points here of the same form, these big long leaf-shaped type points with these ovate tapering bases as they're illustrated here on this slide. The dates again are about 10.600 to 10,000 radio carbon years. This is Folsom in age, if you were in the continental areas of North America.

[00:39:14] Another site a little bit further north, On Your Knees Cave. These are projectile points from On Your Knees cave. You can see again we're getting these large leaf-shaped points, in fact it looks a little Solutrean-like, this particular example. The area I'm highlighting here with the pointer are the actual projectile point bases. This is the bottom, this the part that hafts , they are not Clovis points, they are very different, very distinctive, but they are contemporaneous. These and some of the ones that Daryl found are contemporaneous with the paleoindian tradition in more central areas of North America. These are probably a little bit younger but not by a lot, but remarkably different. There's also more stemmed varieties that occur with this, here's two obsidian points, right here. This is the base of another one. The idea here is they start out as these big leaf-shaped points, very Solutrean almost looking and as they are broken and reworked, they begin to become these tapered points, really similar to the western stem point tradition examples that maybe some of you are familiar with.

Also from the same site, we recovered the oldest human remains found along the Northwest coast, about 9,730 radio carbon years old, which is about 10,300 calendar years old. In the background you see a photograph of the cast of the mandible of a young man whose remains these represent. Across the top of the chart, right along here, you see a scale of carbon 13 isotope values. On your left as you face slide, you will see that right here it marks terrestrial feeders and on the right marine feeders.

When we analyze specimens, animal and human remains, in comparison to this scale we can tell what are the primary compositions of their diet. On the left side of the scale here we see we have beaver, marmot, caribou, black bear, and so forth, very terrestrial-type animals. As we go over toward the right side, we start to get arctic red fox, these are probably scavenging a lot of things off the beach. We have fish, whale, and here's our human, way over here, is a very high carbon-13 value. This demonstrates his diet consisted largely of marine foods, not only that, we know from the nitrogen values, that aren't depicted here that he also ... they are very high, and it suggest that he was eating at very highest tropic levels. In other words, he was eating marine carnivores. Probably some seals, maybe some salmon, and so forth.

If you compare the isotope values from this individual with known isotope values from other archeological sites in the arctic, the very top one here, the Sadlermiut, these are Inuit people from Hudson's Bay who lived on an island in Hudson's Bay. Their diet was virtually 100%, not 100% but a very high marine diet, as you might expect from islanders, and you can see that the delta 13 values here are very high for both nitrogen and carbon. Here's the next one in the table here are Prehistoric Aleut people. These are people who lived on the Aleutian Island chain, treeless island chain that starts about from the Alaskan Peninsula into the North Pacific and, again, very high values. If you look at Shuka Kaa, which is the Tlingit name for the individual that was recovered from On Your Knees Cave, the name selected by the Tlingit people. It means "Person that went before us. Person ahead of us."

The isotope values again are extremely high. This clearly indicates that, at this point in time, over 10,000 years ago, we have clear evidence of a marine adaptation. At this time, sea levels had risen high enough that On Your Knees cave was on an island in southeast Alaska. We saw from the projectile points that there were obsidian points and exotic lithic types, that could only have reached the island through the use of water craft. The diet of the individual clearly shows a maritime adaptation. This is very solid evidence for pre-10,000 year maritime adaptation in this part of the world as well as the use of watercraft. It's impossible to get to these places without the use of water craft. You can't swim to them because of the cold waters and so forth. It would just wouldn't be practical to even propose that as a hypothesis.

What we're seeing here in the Northwest coast is an emerging pattern of large bifacial projectile points. When I was a student we were told that there were no bifacial tools along the Northwest coast. These people probably had either later microblade industries or flake industries. There was no evidence of these big lanceolate points. Of course we're finding those now. Maritime adaptation were believed to be only a mid-Holocene development in North America. We can see clearly now that they were late Pleistocene and probably earlier adaptations.

These are very important evidence and I think that the finds that we have made here are from southern parts of the Northwest coast and northern areas as well, are really the tip of the iceberg. Probably a lot of the story lies on the continental shelves that are now submerged, areas that were refugia, ice free areas during the Last Glacial Maximum, and of course that's one of the areas that we're going to try to look at in more detail, in fact, we have a three year underwater program west of Prince Wales Island in southeast Alaska in searching for underwater sites with no definitive success yet but I'm sure it’s possible.

Returning to our theme here. What I've done here in this slide is present a sequence, from left to right, of the deglaciation of North America in thousand-year time slices. You can see at 18,000 years ago at the height of the Last Glacial Maximum there's no interior route between Alaska and the southern areas of North America south of the continental ice. Even during the height of the last glaciation along the Northwest coast, there are many deglaciated areas and refugia on the continental shelf through which it may have been possible for people to enter the Americas.

By 16,000 years ago the entire coast is deglaciated and available for colonization, whereas the interior route is still closed. By 15,000 years ago, much greater areas of the Northwest coast is developed. We have high species diversity - plants, animals - well-documented throughout the entire region. The deglaciation corridor is just emerging, blocked in many places by large proglacial lakes, sterile of fish, and no evidence of mammal colonization. This pattern continues on through 14,00 years ago. It's not until about 13,000 calendar years ago that the corridor becomes viable enough to support plants and animals and become a corridor for human migration. By 12,500 calendar years ago we have Charlie Lake Cave. We have clear evidence that bison moving from the south, northward, have entered the corridor as well as bison from the north, moving southward, have entered the corridor. The two genetic groups meet in this area. Bison are considered a very good proxy for habitat viability, because they are highly mobile. They can move into an area very quickly and they are in great numbers. They're remains tend to be good index fossils for this type of analysis.

To summarize very quickly, I'd just like to compare these two scenarios. The coastal migration corridor is open and ecological viable by about at least 3,500 years earlier than an interior glaciation corridor. I think one could argue it may have never have been a serious impediment during the last glacial. I think it would have been much easier and more viable beginning about 16,00 years ago. We certainly have a growing body of data for pre-Clovis sites in the Americas. I think the professional consensus is now overwhelming that Clovis is not first and that people reached the Americas earlier. One of the routes by which they may have done this is along the Northwest coast. I think we need to keep our minds open to these other possibilities as well but, in my opinion, this is probably the most viable hypothesis but they are not mutually exclusive either. We may find that over time we have multiple origins for early American populations. This is important in terms of our understanding of the processes of colonization and timing of colonization.

I whizzed through a lot of stuff very quickly and I hope I haven't bored you or lost you. I'll be more than willing to answer any questions or entertain any discussion if you have the time. Thank you very much.

Karen Mudar: Jim, thank you for a great talk. Do we have any questions or comments? Don't be shy, people.

James Dixon: Sounds like one of my classes.

Karen Mudar: I have a question. I was very struck by the points from On Your Knees Cave and the Gaadu Din cave that you showed us. I'm asking about whether or not people have thought about the relationship between that type of technology and what we see further north, in Beringia, and also what we see farther south, in terms of Clovis points. Are people arguing that these are good technological ancestors for Clovis?

James Dixon: No, I don't think that that has been the case. Although it's certainly a possibility. I think most of the discussion has focused on the Western Stemmed Point tradition and I don't know if everyone is familiar with the excavation at Paisley Cave and other sites in the very far west, that suggest the Western Stemmed Point Tradition is actually older than Clovis, at least equally as old. If you accept the Paisley Cave data as older than Clovis. I think some of my colleagues, in fact I was just talking to someone about this yesterday, have hypothesized that the Western Stemmed Point Tradition comes along the north Pacific coast, enters very early and these points may be related to that. I was kind of hinting at that when I was showing how as they are reduced in size, there's large leaf shape points basically evolve into stemmed points as they are used. That discussion has been held that

it's also possible that some, I hate to use so many evolutionary terms, they're the common ancestor for both Clovis and these large leaf- shaped points as well. The finally story isn't in on that but it's a very interesting question.

Michael: I have question. This is Michael Faught. Hi, Jim.

James Dixon: Hi, Mike, how are you?

Michael: Good. Good presentation. Are you familiar with the notion there's a genetic standstill, they’re calling it, at about 15-20 thousand years ago, supposedly, in Beringia.

James Dixon: Yes, I am.

Michael: Is there archeological complex that we can target as that group?

James Dixon: I think so, if one wants to do that, associate the genes with the artifacts. I think one could, given the fact that they are archeologically associated. Those early microblade traditions that I showed earlier from Swan Point, but they're also from the upper Sun River Site, the Bill-John Site in Yukon territory, and a number of other sites in the interior, date very early, 13-14 thousand years ago. This northeast Asian microblade technological characterizes all of these sites in some way, form, or another. There's lots of nuances, I don't know if you want to get into all of that. If you did technologically relate the genes to the artifacts, that would be the most close relationship. It would the early Eurasian microblade complexes of eastern Beringia. That would be very different than what we’re beginning to glimpse on the Northwest coast. I will say that there are microblades on the Northwest coast but it's not entirely clear how far back they go, how old they are.

Michael: It's a fascinating issue, that's for sure.

James Dixon: It's also been suggested that because the microblades are very important in high latitude adaptations in terms of conserving lithic material, particularly in the winter when everything is frozen and you can't replenish your tool stone and so forth, as people moved south they just dropped microblades form their tool kit, is another possible option.

Michael: Thank you.

James Dixon: Sure.

Ann: This is Ann Hitchcock. This isn't directly about archeology but in the maps that you showed. In the area of Manitoba, there was a lake called Glacial Lake Agassiz. I saw on the maps that you showed the Lake Manitoba and Lake Winnipeg that are there now and seem to be there in some form, but I didn't see glacial Lake Agassiz. Why wouldn't it have been represented in one of the periods that you had on your map? It was a huge area.

James Dixon: You're absolutely right. I just left it out because I was focusing on the northern part of this, really from the southern terminus of the deglaciation corridor. If I were to extend this further south, yes, it definitely should be there.

Ann: Okay, thanks.

James Dixon: It wasn't for the fact that I was pretending it didn't exist, I just had to stop it somewhere.

Ann: Great talk. Thank you.

James Dixon: You're welcome.

Amanda: I have a question. This is Amanda Johnson Campbell, I'm calling from Hawaii. Thank you so much. This is a really great talk. I'm wondering is there any evidence for a study being done on the actual water craft that would have been use?

James Dixon: Well, there really isn't. The extreme skeptics, that's what they always bring up, "Well, unless you find a boat, we're not going to believe it." The chances of finding - it doesn't even have to be a boat, it can even be a raft or some type of water craft - the chances finding something like that are very slim. It's possible that there could be some examples in the muds on the continental shelf and so forth. I think the inferential evidence is overwhelming with the occurrence of obsidian, quartz crystal, these types of exotic lithic types on these islands, that people had to transport them there. They could only do that with water crafts.

The fact that they themselves were there requires water craft. I think that's a bogus argument. In terms of the water craft themselves, I wouldn't be at all surprised if we're not looking at skin boats here of some type. These are really well adapted for sea ice conditions, easily manufactured in areas where there's small wood supplies and so forth and they appear to have long history in the Beringian archeological record, anyway. We know that people used water craft. We have in northern Japan and areas in the Amur River and so forth, for 20,000 years at least because we have archeological remains on these islands. There's good evidence from Asia. The actual type of water craft is a very good question. If I had to guess, I would guess skin boats but it could be a variety of other types as well.

Amanda: Thank you.

James Dixon: Sure.

Michael: This is Michael Faught again. I just wanted to add that while you can't find the boats all the time, there's more and more evidence of the tools that are used to make those boats and that can be a way to track down as well.

James Dixon: Yes, very good point. In fact, I think that Dennis Stanford believes he has some of these types of artifacts in very early sites on the east coast of North America as well.

Ann: This is Ann Hitchcock again. Does oral tradition in the Northwest coast Native communities relate to the theories that you presented here about where they came from and so forth?

James Dixon: That's a very good question. I've worked closely with the Tlinget people who live in this area and they even participated in the excavations and in some of the publications. Yes, there is an oral history that describes people moving, about the sea level getting higher every year so people had to keep moving higher, higher, and higher, and back from the ocean as sea level rose. Of course there's no firm dates for this but when we would do the archeology and the geology, people would say, "Oh, that's when that happened." They liked the research because they can fit it in the oral history. It would give a year chronology. That to them was very valuable and complementary to their knowledge. In terms of ancient movements of people long ago, that's a different story. There are many groups and they moved around a lot. It's hard to tell at what time period some of these histories are set. That’s a little trickier. I found that much trickier.

Ann: Interesting. Thank you.

James Dixon: I think that's fascinating. I will say something on that topic. When the human remains were discovered, the people there were very curious. They fully accepted this individual as an ancestor. It wasn't it like “Could it be some other type of person or group of people?” The dietary information from the isotope analysis was very important because for them it showed - it demonstrated a long history use of marine resources which are very important today and, of course, contentious in terms of commercial fisheries and traditional subsistence's rights and so forth. It's been a fascinating experience.

Karen Mudar: Jim, would you care to comment on how people might have made their way around the Aleutians, if they're working their way down the coast. It seems that would have been a pretty formidable set of almost continuous islands, I guess it would have been a pretty continuous peninsula at that time.

James Dixon: Good question. The archeological evidence, at least as we know it now, is that the Aleutian Islands were colonized from the east to the west. People from the Alaska peninsula moved out on the ... Actually, some of the nearest Aleutian Islands were part of the Alaskan peninsula during late Pleistocene and then early Holocene. That area was occupied and people moved westward along the island chain that's about 1,000 miles long, westward, and the archeological sites, based on the ones we have discovered and been able to date, suggest they get younger and younger the further west you get. If this coastal migration model is correct, people would have come along the southern margins of the Bering land bridge until they came to the Alaskan peninsula and then slowly migrated out along the Aleutian Island chain from there, if all these data prove to be correct. What we don't know is just phenomenal compared to what little we do know.

Karen Mudar: Yes, of course. Given that all these folks are hunter-gatherers, it doesn't seem like you can point to population as a mechanism for pushing colonization of the New World. It seems more likely that they're following mobile herds of animals. Has there been any attempt to model population growth among bison or caribou?

James Dixon: I don't know about that. I think there are two different scenarios. One is the terrestrial migration, or moving the people across the Bering land bridge. This probably happened. We have good evidence of these microblade traditions in Northeast Asia and then in Alaska and the Yukon 14,000 years ago. There may have been something really different happening, and these would be terrestrial land mammal hunters and fishers, but along the coast there may have been a different scenario. Particularly the Northwest coast and the Gulf of Alaska because now we're dealing with relatively narrow, even though it's very – a quite broad, strip of land that's bordered on ice one side and the ocean on the other. I'm not sure that population pressure wouldn't have been a factor in this and it would have forced movement uni-directionally in a very tight biotic corridor, what John Erlandson called a kelp highway. It would have been first westward and then southward. I think there might be different models there. In terms of actual modeling human dispersal, in terms of herding animals, I think there has been some work done but it's not my area of expertise. Sorry.

Karen Mudar: Very interesting, though. I have one last question for you. What do you think submerge sites might look like? If we're going to start thinking about or start proposing research to look for sites on submerged portions of the continental shelf, what are we looking for? Are we looking for open air sites? Is there any likelihood of cave sites, like the cave sites that we're seeing along the coast now? Are we looking for fish weirs? What would you predict or think is going to be our most profitable or likely place to look for sites?

James Dixon: I think that's a great question and Michael Faught, who is online here, is one of the pioneers on this. It's great he's here and you can talk to him too. I think a lot of us recognize the continental shelves as really the next big frontier in North American archeology, geographic frontier. What's out there, I would expect, is going to be an extension of a lot of the things we see on land. We know there's submerged caves and rock shelters, certainly a possibility. There's a number of us that have done various modeling and other types of ways to identify likely site locales on the continental shelves. This work is all in it's infancy.

For example, Quentin Mackie and Daryl Fedje and other have been looking for evidence of fish weirs along the coast of British Columbia. I was looking for habitation sites of the coast of southeast Alaska. I think Michael has been looking for habitation sites as well, following the river channels, seaward. Michael, you should pipe in on this, but in the Gulf of Mexico and so forth. I think we'll see a wide variety of sites and we can see some of the things like shell middens submerged, and other things as well.

Michael: Yes this is Faught. I couldn't agree more. The notion that this is a terrestrial analog we're looking for. We're looking for the kinds of places, the landscapes that we're familiar with for sites is a way to go. It's definitely localized to different areas so that the Northwest coast is certainly different than southern California is different than the Gulf of Mexico. Each area has its own particular things. It's for sure that Dixon's work in the Northwest coast along with Monteleone, his ex-student, and the Canadians, is just cutting edge, absolutely, and in the right place to look for coastal migration. There can be no doubt.

Karen Mudar: Thank you for that commentary. I wanted to add that Michael is going to talk in this series later in the year, I think in January. We're looking forward to your talk as well.

James Dixon: That would be great.

Michael: I just have to put it together.

Karen Mudar: Well, get started! Do we have any more questions or comments for our speaker? No, well don't forget we have a talk next week. I want to thank Dr. Dixon for such an interesting and stimulating talk today.

James Dixon: My pleasure. Thank all of you.

- Duration:

- 1 hour, 8 minutes, 4 seconds

E. James Dixon, University of New Mexico