Last updated: February 8, 2022

Contact Us

Article

Dams Alter the River: Part One — BTS Podcast 10

NPS

-

Dams Alter the River: Part One — Behind the Scenery Podcast #10

Welcome to the water world at the bottom of a mile-high desert! In today’s episode, we'll explore how the Glen Canyon Dam changed the Colorado River through one story about wildlife struggling to survive in a damned world. The big picture of development invites you to consider ongoing inquiries about how to balance the stuff you need with the life you want to see.

- Credit / Author:

- Behind The Scenery Podcast

- Date created:

- 03/02/2021

[Audio: water splashing noises]Bob

We’re walking upstream in the little gorge below the barrier fall at Shinumo to our second net in a pool in a tight, dog-like turn where yesterday we saw at least four humpback chub. Hopefully, some of those fish will be in the net.

Kate

Hidden forces shape our ideas, beliefs, and experiences of Grand Canyon. Join us as we uncover the stories between the canyon’s colorful walls. Add your voice for what happens next at Grand Canyon!

Kate

Hello and welcome. My name is Kate. You are listening to Behind the Scenery.

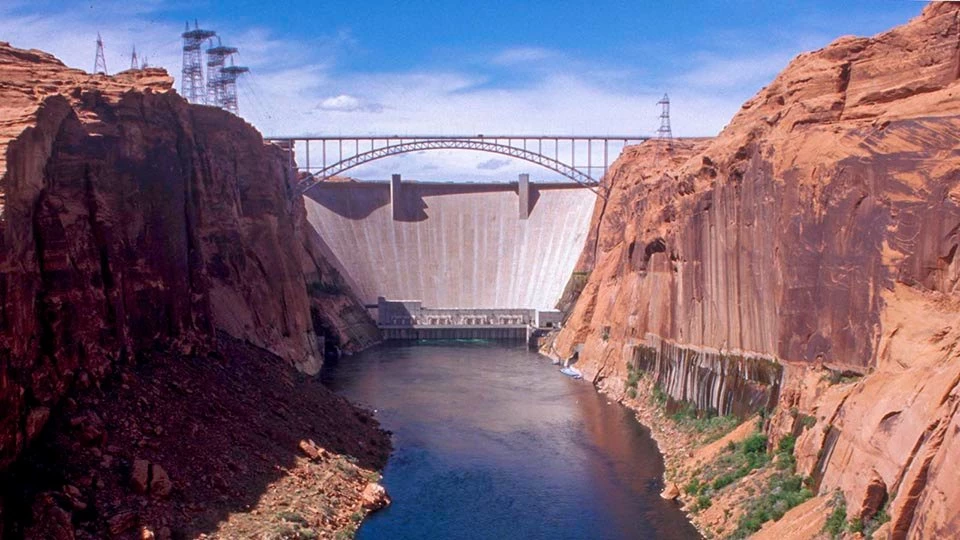

Welcome to the water world at the bottom of a mile-high desert. Tributaries and streams flow down steep cliffs and side canyons to meet at the river. The Colorado River in Grand Canyon is sandwiched between dams at both ends of the park, Glen Canyon Dam at the top and Hoover Dam at the bottom. After Glen Canyon Dam blocked the river in 1963, people started noticing that it impacted the community of animals and plants at the bottom of the canyon. The dam altered the riparian world downstream. A wave of change hit the aquatic environment– that’s home to water bugs and fish! It changed the river for people too. In today’s episode we are going to explore how the Glen Canyon Dam changed the Colorado River. We’ll share one story about the struggles of wildlife to survive in a damned world.

Bob

So let's talk about what the River was like prior to dams, just to draw the contrast.

Kate

This is Bob Schelly. He is a fisheries biologist for the Native Fish Ecology and Conservation Program at Grand Canyon.

Bob

So the Colorado River, which is a big desert river draining pretty arid landscapes. Pre-dam is characterized by really large snowmelt-driven spring runoff events and so it was typical in a spring runoff to see flows through Grand Canyon in excess of 120,000 CFS, so that's a cubic feet per second…

Kate

A cubic foot is about the size of a basketball. So imagine 120,000 basketballs flooding past you every second.

Bob

So you have these big sediment-laden spring floods and then during the summer the river levels would drop to comparatively low base flows of 5000 CFS or less. And in addition, those floods would carry lots of driftwood, woody debris, they would build enormous sandbars and create backwater habitats related to the deposition of sediment and there would be a temperature difference. You have very warm water in summer and of course in winter at base flows, the coldest temperatures, close to freezing.

Kate

A flood that big was like flushing the toilet, a big whoosh down the canyon...It purged things, but also brought nutrients into the canyon body... It was like a seasonal detox.

Bob

Post-dam pretty much all those details have changed. So now the reservoir upstream, Lake Powell, behind Glen Canyon Glen Canyon Dam, captures big spring runoff so you don't see a pulse. So it's in effect it's flattened that hydrograph. You no longer have the big floods through the Grand Canyon, and the base flows don’t get as low as they did historically.

Kate

The canyon used to have a pulse, a heartbeat that ran with the seasons. The dam flatlined that pulse....if the river is the heart of the canyon, the dam changed how that heart beats.

Bob

But you see more daily fluctuations because the dam is generating power and at peak power demand they increase the release. So over a 24-hour cycle, you see rise and fall of the River, which in the in the years right after dam closure, was quite extreme.

Kate

And it was extreme for humans too. There are people on the river in Grand Canyon, floating on rafts and kayaks, navigating rapids all the time! At night, they tie in their boats, big enough to carry 15 people, to stakes on the beach and settle in to sleep to the sound of the river.

Bob

You hear stories about people boating through Grand Canyon and waking up after a night’s sleep and finding their enormous S-rig 10 feet up on the beach, just stranded. These days that daily fluctuation is less. It might be on the order of 1 1/2 or two feet but you have daily fluctuations and a more constant hydrograph throughout the year. And it's a cold clear release because it comes out of the bottom of the reservoir, so in summer now the river is very cold which didn't used to be the case, and in winter the water is actually warmer than it would have been pre-dam

Kate

The River is so cold, it's really hard to swim in! The changes that happened to the Colorado after the dam changed many aspects of the corridor in Grand Canyon from the size of beaches to the experience of voters to the lives of the plants and animals that depended on that watershed. So today's story goes underwater with the fish. Let's meet Rebecca Koller who has a long career at Grand Canyon, extending back over 20 years. She had her start in the vegetation program and began with fisheries in 2016. Rebecca is now the natural resource specialist for the Native Fish Ecology and Conservation Program.

Rebecca

So yeah in Grand Canyon originally there were eight native fish in the Grand Canyon river and six of those are endemic

Kate

Endemic means that creature only lives in that geographical location. So these endemic fish are special because they only live in the Colorado River watershed that's around the Canyon.

Rebecca

And four of them have been extirpated and two of them are now endangered.

Kate Let’s look at that word extirpated. It's similar to extinction in that they have disappeared, but instead of disappearing from the entire world, they've been rooted out of a local area, similar to how grizzly bears, which are on the state flag of California, are extirpated from California today.

Rebecca

So I might have mentioned the Colorado pikeminnow has been extirpated from the Colorado River through Grand Canyon. It does still exist I think in pretty low numbers, huh Bob, in the upper basin. Yeah, they’re declining. And that was that was one of the one of the large predatory fish and the other ones that have been extirpated from Grand Canyon is the bonytail chubs, the round-tailed chubs and is that it? Yeah. And the pike minnow. Rite, rite. So and then the other two that are endangered or the humpback chub and razorback suckers.

Kate

Out of the eight original native fish, the humpback chub is a crowd favorite.

Bob

the humpback chub is special within this group in that they’re long lived fish, 40 plus years, and they’re, they’re habitat specialists in canyon-bound regions. So pre-dam humpback chub were not widespread throughout the basin. They were found in canyon reaches that have would have big rapids and deep water within gorges that have this pool-rapid kind of morphology.

Kate

Within the mile-deep gorge of Grand Canyon, the river pools into eddies after going through rapids with waves taller than people. It was the perfect habitat for the humpback chub! What else is cool about the chub? When you look at it, it has a face kind of like the canyon mules. This narrow, rounded face, and above that face rise a big hump.

Bob

And large adults develop this weird fleshy hump that sticks out above the head and there have been a number of theories why because its not just humpback chub, it’s the razorback sucker, you can tell by the name, that feature above the head that makes them deep-bodied. And the theory that I like most, and I think there is some experimental evidence to support it, so why multiple lineages evolve this feature this humpback like feature is that Colorado pikeminnow which was the one big predator prior to invasives gaining a foothold in the basin, are gape-limited. So they can't open, even though they get very big, pikeminnows can get 6 feet long, at least they did historically, physically opening their mouth is surprisingly limited for as big a fish as they are. And it turns out that humpback chub and razorback sucker, once they reach a certain size and the hump starts to develop they become invulnerable to predation. They don't fit into the mouth of pikeminnow except the very largest pikeminnow.

Kate

These fish evolved, especially to interact with each other, in this specific place. This doesn’t happen everywhere! So we are looking at a predator and prey relationship that went on for centuries before the river was dammed....time enough for our chub to evolve one mean hump that was too big, and too tough for the shark of the Colorado to swallow! Now that the dam is here, the entire population is completely caught in the Grand Canyon between the two dams.

Rebecca

Sure, yeah, so as Bob mentioned earlier, the humpback chub is the largest population of that chub remaining in Grand Canyon and it's centered around the little Colorado River and it's sort of thought of as the center of the humpback chub universe. And so as a result of the dam operation, it was identified as a conservation measure to establish another second spawning aggregation of humpback chub within Grand Canyon, recognizing that that little Colorado River population is, you know, it's still vulnerable to catastrophic events. Say weather events, flooding or contamination or whatnot. So, so it was identified that that was important to establish that second spawning aggregation and so I think in the 2000s or around 2000 there was a study published looking at potential other locations for translocation, other tributary locations, and in that study it was identified, three sites were identified. They identified Havasu Creek, Shinumo Creek and Bright Angel Creek as potential translocation areas that would support humpback chub population. And they were looking at like water quality, temperature and then also the presence of non-natives

Kate

Remember this?

Bob

We’re walking upstream in the little gorge below the barrier fall at Shinumo to our second net in a pool in a tight, dog-like turn where yesterday we saw at least four humpback chub. Hopefully, some of those fish will be in the net.

Kate

Between 2009-2014, a fish crew at Grand Canyon began pro-actively reintroducing humpback chub to Shinnumo Creek, giving them another home to recover from the dam.

Rebecca

And all indicators up to that point where that the fish were doing well, they were, they were growing and surviving in Shinumo Creek. And then in 2014 there was a fire on the North Rim and subsequent flooding into that Shinumo drainage which essentially wiped out all of the all of the fish population in that Creek including the humpback chub, bluehead suckers, speckled dace and all other fish species there so, so it was, it was I think what is interesting about that whole project was again we learned that you know these populations of humpback chubs continue to be vulnerable to those catastrophic events. Fortunately, we've done work in Havasu Canyon and Bright Angel.

Kate

When you have an endangered species like the humpback chub that only lives in a small area, a catastrophic event like a fire or flood could cause them to go extinct. In order to increase the habitat range of the humpback chub, the fisheries crew would have to tackle another problem, the fact that invasive species are outcompeting the humpback chubs in the creeks they once called home.

Rebecca

So we started electrofishing the entire reach of Bright Angel Creek, which is about 13 miles, in 2012. And that effort involves backpack electrofishing with crews of, you know, 6 to 10 people.

Kate

I met fish crew down in the backcountry at Bright Angel campground and joined them in the water as they pounded in a weir that would keep non-native trout out of the creek. Afterward, we met back in a roundtable at the employee cabin so that we could get the scoop on non-native fish removal.

Nick

Ok, my name is Nick. I've been involved with this project for quite awhile now. I forget how many years, but I guess my favorite part about this is you're in this pretty magical place. In my opinion, you're doing really good work. Work like I mentioned earlier, we're restoring these native fish or we’re trying to restore their habitat. Yeah and I guess get to outreach to people and explain what we're doing and especially having those people, some of them have come and volunteered on our crew, and just, I guess over the years we've seen people with a negative outlook kind of switch to a positive outlook and we're seeing more native fish and more people that are on board with this.

Mike

Uh, my name is Mike. I've helped out with this project on and off since 2012, and I've also done fisheries work throughout the Colorado River with similar fish as down here. And it's just kind of cool working on this project which is, you know, it's the same goal as projects elsewhere that I've worked, with the same species, different place. And I don't know, it's just it's cool being a part of the project that has gone on for this long and is really great people working here.

Ray

My name is Ray. I have been a technician here for this week is my sixth season on the Bright Angel crew and what I really like about this job, in this position, is that you know, this being my sixth year, and working the last five years you actually notice a difference every year as you work down from the source all the way down the Colorado River 13 miles of electrofishing, you can see a difference in less and less nonnative fish and more and more native fish. So I think the biggest thing for me is just being able to see that difference over a period of five years. It's pretty awesome! Makes you want to keep coming back keep doing this work, and another thing is just in terms of the job, the place you get to work in the bottom of the Grand Canyon. That's pretty awesome! People you work with are pretty great, so my best friends I met on this job. And it doesn't help that my supervisor is in the room but the people you work for us agree and not just saying that 'cause he's in the room here, but I really do think that yeah, you work for great people with great people, in a great place. It's pretty awesome.

Nick

So I guess we're down here I the main goal is to create a habitat friendly for the humpback chub which historically lived in bright Angel Creek or at least it's assumed at least down in the River like Delta area of right Angel and there are lots of Brown and rainbow trout in it now thanks to some people back in the early 1900s stocking it who worked for the Park Service.

Kate

Yes, Rangers were stocking creeks in the 1920s with sport fish from Europe like brown trout and rainbow trout. There are pictures of rangers on mules slung with old milk cans full of non-native fish. In Bright Angel canyon, rangers were even operating a fish hatchery to actively stock the creek with lots of non-native babies. The non-natives flourished after the dam was put in, out-competing local fish and interrupting the river food chain. Today’s fisheries crew had a lot of work to do, or undo, in Bright Angel Creek.

Nick

I guess the whole goal of the project is to protect the resources within the park for future generations and unfortunately our predecessors did put nonnative fish into the creeks, but now we're restoring those native fish that are here or at least making it making the habitat available for them so they can potentially persist into the future for future generations to come experience.

Ray

Nick that was beautiful!

Nick

Thank you, Ray.

Mike

I guess we can talk about how the tributaries within Grand Canyon are kind of like a stronghold for the native fish. Well, could be. I guess the River is highly modified. You know Glen Canyon dam is up there releasing cold, clear water that's super unnatural for this river’s historical flows and sediment load and so the tributaries are really important to the native fish for spawning and for, you know, the like rearing of younger fish and so this is like just one little piece of a larger effort to like restoring the chubs as there's other projects in another tributary or two restoring the shed.

Ray

Well I may not be as qualified discussed this, but just from personal observation from talking to people who have been coming to Phantom ranch for 10s of years, one observation it could be from trout removal or not but trout kind of prey on macroinvertebrates and so I think people notice more birds entering the area that are feeding upon flying insects that may be where otherwise have been consumed from trout. But now that niche has opened, more insects maybe include some more birds. Coming to think, the last Christmas bird count they got a high species richness count.

Kate

One of the concerns about the brown trout is they aren't just outcompeting native fish, they are eating everything in the creek, from the small native fish like speckled dace to those aquatic insects which start their lives underwater but become flying insects like caddis flies and mayflies. They are the base of the food chain for a lot of birds. One of the neat things that I've observed in my time down by Bright Angel Creek is over the past couple years, I'll never forget the first time I saw a great blue heron going through the creek and catching those little speckled dace minnows. The amazing thing is you likely would not have seen a heron there five years ago because the trout had eaten out their traditional food source.

Bob

I would say a benefit of trout removal is this expansion and really increasing numbers of native fish is an although some of these natives are endangered and still can't be angled in sportfish yet. I think one day that should be an ultimate goal because fish like the humpback chubs and round tail in the upper basin and maybe one day in Grand Canyon, the large native predator pikeminnow which could grow up to six feet long. I think that one day those fish could be very appealing to people to angle the native fish that evolved in this system. And for people who are trout enthusiasts I think there are plenty of places to go and fish for trout in their native range but one day I'd like to see Grand Canyon as a destination for anglers who are interested in fish diversity where it's found naturally and it would be the experience of a lifetime to catch a large pikeminnow in the Grand Canyon. For me that would be angling gold.

Nick

It is about 13 miles from the source all the way to the confluence of the Colorado River so it's pretty cool we get to start up in October basically starting at the source Rangel Creek actually consists of Roaring Springs and Angel Springs and we were fortunate enough to be able to shock up the entire length of Roaring Springs an Angel Springs in October and then by around February ish mid January we make it closer to the confluence and it's pretty cool because as we start up at the top at Angel Springs it's the leaves are starting to change and then throughout the season's working or wait downstream we dropped elevation chasing fall all the way down to confluence since it's kind of cool that you know we just work with the leaves as they change.

Kate

As I went out on my winter backcountry patrols, I would look down on a team of women and men and waiters in their hands were yellow human sized ones that they would jab into the water.

Nick

excited about that the description just because anytime were shocking in the stream is 2 Electro Fishers so there's a it's a backpack base that you wear and there's two of 'em so they'll be two people wearing them should have followed by netters people getting fishes or shocked up in bucket or his people bucking fish that are netted anyway long story short people when they walk past us on the trail they make the job you probably hear this joke you know once a day twice a day but at least once a day that looks like we're Ghostbusters big square backpacks watching ghosts down there nude talk with them or tell about little bit about the project and what we're doing is really good public outreach

Mike

I feel like like we're walking on bowling balls.

Bob

What’s that show?

American ninja warrior. Climbing over cascades, through overhanging vegetation and climbing up over waterfalls. It's pretty arduous getting up the creek and sometimes people can slip and top their waiders and you know, need to take 5 but it's it is an adventure getting up the creek.

Kate

Working in fish crew requires a blend of wilderness skills and meticulous data collection.

[Sound clip of collecting data with splashes and Enya playing in the background]

Mike and Bob and Nick

Well everyone, the whole teams in in the creek. You’ve got your two shockers up front and when the whole team's down there, you say, “Ok, everyone ready?” and then you say, “OK shocking!” You check your time and the shockers put their thumbs on the on the anodes button and we're off and any any trout that are within like an 8 foot radius of the the wand will be drawn into that anode ring at the end of the wand. And after, if they reached a distance from that they'll go…What's the word? Techne. But they just just like when they're knocked out. What’s a scientist word for knocked out can sort of pretend to understand. OK so they’re stunned once they get close enough and thankfully the creek is really clear and sometimes they might get stunned deep down or sometimes they shoot across the field but usually you can see them 'cause they got a white belly and they kind of flash and netters Test will scoop them up. Sometimes if you're in a big cloud of dace they'll just be flowing downstream like they look like leaves or something they just keep coming and coming and coming. But yeah, we're mostly just scooping every single fish we see and putting them into buckets filled with water. At least the natives get the buckets with fresh water and then next we dispatched the the trout and put them in the dead bucket for processing later. Yeah it's pretty exciting sometimes when the water is flowing pretty fast and in a group of there's five to eight of us in the stream and we're trying not to fall, we’re slipping around and then shout and Fisher shooting like 3 legs the waters fans were trying to net fish and or like hey

Kate

For the past decade, fish crew would return each fall. Over time, what they found in their studies started to change.

Bob

So when this project was initiated in about 2012 trout both Brown and rainbow trout were the predominant fish species in the Creek and they were very dense so that over the course of a whole season more than 10,000 trout were removed whereas today we've succeeded in reducing trout by more than 95% and last winter we removed only around 300 Brown trout so that's very successful suppression effort and the other side of that coin is that we've seen a real rebound of native fish is both in numbers and in their range.

Kate

10,000 trout in the creek meant buckets of non-natives lined the creek. This is a huge success story in Grand Canyon. In today’s world, isn’t good to hear about a species coming back from the brink? Now finding a non-native fish can be it’s own challenge. It’s a big deal!

Ray

It's pretty exciting sometimes when the water is flowing pretty fast and in a group of there's five to eight of us in the stream and we're trying not to fall. We’re slipping around and then trout and fish are shooting like through our legs. The waters running fast. We’re trying to net fish and or like, “Hey Mike!” is officially over there. Gets it. Jumps, jumps across the channel, scoops up the fish! I got that trout! I got that trout! And then it's pretty exciting, and then if we're up top like around Cottonwood, we maybe we haven't seen any native fish yet and where, you know, the water is flowing super-fast and we're trying not to fall again and, you know, these trout going between our legs. We’re netting. All of a sudden someone pulls up the net and there's a, there's a maybe a flannel mouth or bluehead sucker in there and we're like, “Yeah! first sucker of the season this is awesome and just kind of very exciting very exhilarating it's almost like it's almost like we're ghostbusting separate trout busting.

Mike

Trademark! Yeah, the trout are very, they're quick, so you can't. It takes awhile for you to hone in on like, just where do you stick your net when you see them? It's kind of, it's like a game almost, like tennis. I don't know, go for the head.

Nick

Or hockey, a lot of people who play hockey are pretty good at netting. Another thing too is with larger trout especially for entering a pool they can feel that electrical field before hand and it's often that they'll charge at us to try and break that field, so sometimes they won't actually. You have to bring you’re A-game if you want to catch those trout, and that's what our goal is.

Mike

Yeah, the big trout are the ones we're after because we're going in during spawning season and so we want to get the big ones that are carrying the most the eggs, you know, and the ones that are going to produce a lot of offspring. And so if we catch a big trout, that's that's a big deal that we're cutting out possibly hundreds of offspring that could be, you know, raised in the creek the following year. But also getting little ones is just as important.

Mike

Which brings us to the end of the day. So we're removing brown trout and rainbow trout from the creek and this kind of ugly part of the creek or the project, but also kind of cool. Every trout that is removed from the stream is used for beneficial use. We don't just, a lot of other removal projects you just throw the fish along the bank or sink 'em but every single trout that we take out of the creek either goes to human consumption or to aviaries at the Hopi and Zuni reservations. And so every fish we catch we are cleaning or bagging them and we're carrying them all the way back to the bunkhouse and putting in in vacuum sealed bags and freezing 'em and the next time the helicopter comes down we send them out.

Kate

What makes this fish program unique is that none of the trout are wasted. Each trout is used for beneficial use for people or other animals, and this was brought about in collaboration with Grand Canyon’s Traditionally Associated tribes. These are people groups that have called the canyon home for thousands of years. Many of the tribes expressed concerns about how the program was operating in a sacred space.

Kate

At this point, we're going to explore an oral history conducted by Paul Hirt of Arizona State University. We're going to listen to clips from his interview with Kurt Dongoske who has been involved with the Glen Canyon Dam Adaptive Management program since 1991. Kurt was the director and principal investigator for the Zuni Cultural Resource Enterprise and often represents the Zuni tribe on issues related to River management.

Kurt

Anyways, so when I was at Zuni in 2008, um, a Zuni religious leader came in and asked me, “Are they still killing fish and the Grand Canyon?”…………….I said, yeah. He said, “That’s not right. They should stop that.” And I said, “Well, why?” And he explained to me, well he explained to me this story…..

Clip from Zuni in the Grand Canyon film

The Eastern travelers came to the Little Colorado River where the Haiyutas warned them that as they crossed, they must hold their children tight. Then in the middle of the river, they children began to turn into water creatures. Fish, turtles, frogs, and snakes. Some parents dropped there children into the water where they were lost. They mourned but when they came to the place of the Co Co they heard singing. They were the spirits of their children. Thus all aquatic life are the ancestors and kin to the Zuni People.

Kurt

That event: that all aquatic beings are Zuni children, are viewed as Zuni children, whether they’re native or not native doesn’t matter. And so from a Zuni perspective, you are killing these fish, you are killing Zuni children. You’re killing beings that Zuni has a special relationship to.

Kurt

I think there’s a lot of, a lot of benefit that western science could take from the Zuni perspective of this sense of stewardship in the sense that the environment that you’re dealing with is composed of multiple sentient beings and that your actions on that environment have consequences, long-term consequences. I think it would make scientists much more respectful of the animals they handle, how they treat them, how they deal with them, what sorts of projects they want to design.

Kate

Let's hear from another oral history of Leigh Kuwanwisiwma who was director of the Hopi Cultural Preservation Office for thirty years. He is the leader of the Hopi Tribe and has been involved in the Adaptive Management Plan in Grand Canyon on the river since around 1989.

Leigh

The big one is the electrocution of those trout. That was a big controversy initially to Hopi cause we were the only one who commented on that proposal. So our record stands that one the initial area that they were going to zap those trouts by the thousands was right at the Confluence, you know, a sacred site. A very sacred site to us. You know. And it encompasses this kind of concept of the spiritual domain. So, well, it’s our finality, as I told you, it was also the beginning of our spiritual life. I one day hope to become a Cloud Person to visit all of you people. That’s how we believe. So it’s the beginning of life for us. So, our [road noise]– I said to Kurt, you know how I would best explain it? Is that they kill all these fish. They’re taking life away from living creatures. And Hopi, when they do their prayer feathers and prayer offerings, it’s for the perpetuation of life. It’s not for the end of life. Nah. So even though that proposal had a purpose, because the effect on the humpback chub, and overpopulation, you know, it just didn’t sit well with me (road noise and wind noise). If they dare do that, it’s going to create this aura of death. That was our argument.

Rebecca

As many people know, Grand Canyon is sacred to a number of native tribes in the area. And our work was, you know, it, it has significant impact to, to non-native fish in Grand Canyon and that was of concern particularly to the Zuni tribe. The work that we're doing in Bright Angel Creek which is removing the brown and rainbow trout, was of concern to the Zuni Tribe. Their, a very sacred place to them is Ribbon Falls. And so it was through lots of consultation with them and other tribes that it was decided that all, all fish that we remove from, from Bright Angel Creek or, or otherwise, will be safe for human consumption. So all of the fish that we take out of Bright Angel Creek we clean and freezer seal and then we'll take that fish and it becomes, we’ll fly it out and it's available for, for others, you know to, for human consumption. We've delivered fish to Zuni as well as Hopi and Navajo. Some of the smaller fish that we remove from the creek that's not easily cleaned we’ll freeze and we’ll give that to tribes for their ceremonial eagles. And so we delivered fish to Zuni to their aviary, we've also delivered fish to Navajo to the zoo there. So we try you know, as much as it's feasibly possible, to, to save any of the fish that we, we take from the creek or the river and give, you know make it available for people or, or animals, other animals. So I think that's really important component of the work we do. You know there's just a lot a lot to consider when we do any kind of conservation or restoration work in Grand Canyon, and there's I think it's important to recognize the other, the tribes that hold it sacred.

Kate

The damage caused by Glen Canyon Dam is done. So now what do we do after the fact? How do we manage a degraded ecosystem? How do we protect the resulting endangered species and how do we do so as human beings with a respect for life? These are the negotiations we face. In December 2020, National Geographic published an article “Human Made Materials Now Equal Weight of All Life on Earth.” A quote from the article reads, “The total weight of everything made by humans from concrete bridges and glass buildings, to computers and clothes is about to surpass the weight of all living things on the planet.” Many theorize we are about to enter a new era, the Anthropocene, where humans are the dominant force shaping the planet. At the start of the 20th century, the mass of human created stuff weighed about 35 billion tons; today it's 1.1 trillion tons. That means every person generates more than their own body weight of manufactured stuff in one week. As countries across the world continue to develop in a global economy, over the next 20 years that stuff is predicted to double. Projects like Glen Canyon dam are exponentially growing all over the world. Creatures like the humpback chubs are being driven to the brink of extinction. Places like Grand Canyon National Park are some of the only safe havens left on earth for plants and animals, places they don't have to worry about crossing the road or having a house built in their backyard. Let's wrap up with a question we can all ask ourselves. How do you balance the stuff you need with cultivating a richer life? My name is Kate and thank you for joining us on another episode of Behind the Scenery. We gratefully acknowledge the native peoples on whose ancestral homelands we gather as well as the diverse and vibrant native communities who make their home here today.

Acknowledgments:

Special thanks to Paul Hirt of Arizona State University for his permission to use his audio from the GCDAMP Oral histories he conducted.

Special thanks to Kurt Dongoske and Leigh Kuwanwisiwma for their support in using their interviews.

Special thanks to the fisheries team for going above and beyond in both interviews and collecting audio in the field.

Thank you to Jan Balsom and Mike Lyndon for support in the podcast development.

Produced by Ceili Brennan and Kate Pitts.

Music and sound engineering by Wayne Hartlerode. Special thanks to Joe Scrimenti for contributing his song “Invisible Present.”

Welcome to the water world at the bo

Behind the Scenery Podcast

Hidden forces shape our ideas, beliefs, and experiences of Grand Canyon. Join us, as we uncover the stories between the canyon’s colorful walls. Probe the depths, and add your voice for what happens next at Grand Canyon!

Listen to more episodes here on nps.gov >

Or on Apple Podcasts >