Last updated: April 7, 2025

Article

Cultural Landscapes of Austin Park System

NCPTT/National Park Service

Kim McKnight: My name is Kim McKnight. I work for the city of Austin Parks and Recreation Department, and I can't tell you how excited I am to be here, and really just by the mere existence of this symposium, I'm sure like many of you, there's a lot of really great stuff, as Evan mentioned, and when I was thinking through some professional development opportunities in the spring, even before I was asked to be a speaker, I went, "I've got to be there." This is a really an intersection I think for so many of us that we're quite passionate about and have so few opportunities to explore with each other. So I'm excited to be here with you all for the next few days, and I hope this is something we can continue because this is very exciting stuff.

And again, Robert Melnick is a very hard act to follow, so bear with us. It did provide some food for thought as we present. So I hope you'll enjoy what we have today. I would be remiss, there's a couple people I think are really important to the Austin Parks and Recreation story that I'm about to tell, and one is my colleague Sarah Marshall who's here, and if you get a chance to talk with her, she can fill in some blanks over the next couple of days. And one of our really great stakeholders is here, Charles Peveto who is I think responsible on the activism and advocacy side for protecting so many of our Austin historic resources. So, two people you should be sure to follow up with over the course of the next few days.

I would like to preface this by saying that when I came to the city of Austin's Parks and Recreation Department in 2010, I was finishing my thesis at the University of Texas in Michael's program, and I saw an advertisement that said they were looking for a graduate level intern to do a historic resource inventory of Austin's park system. And I thought, hmm, that sounds pretty cool. I'm a native Austinite. I know the park system pretty well. That sounds like a great job. So I did start there by doing a GIS based inventory of the park system. And one thing led to the other, and they had a lot of issues. No historic preservation person on staff, a lot of historic properties, and there was really no position for what I did. And I will say, it's taken about 10 years, but we've managed to create a real program and create a programmatic approach to the identification and the preservation and rehabilitation, and ultimately stewardship of our historic resources in the park system.

I've only recently been able to get some additional help through some staff members, so I've been kind of a one person show for many years. But we are just getting started. And I'm really here to give you… I've just sort of cherry picked a few really interesting, I think, examples of municipal parks and the stories that they share. We have a lot of work to do. There's a lot I'm going to show you that is kind of a work in progress, but we do have a few successes under our belt as well.

For those of you who may have attended the boot camp, you probably got a great lesson about what cultural landscapes are, and I do agree that there is no such thing as wilderness. The idea of a pristine environment untouched by man is something that I don't think really exists. And I think once you acknowledge that all landscapes, whether in a municipal park system or anywhere in the world really, have likely had some intervention or some impact by humans, you really do start to see the world in a different way. And I think park systems in large metropolitan cities like Austin are so interesting and have so many great examples, which I'll share with you today.

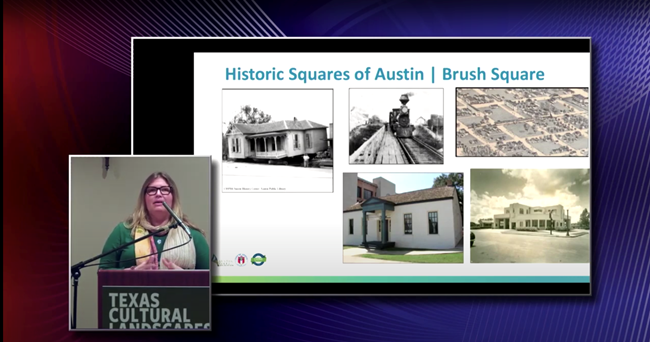

So just briefly, I'll go through just a few examples. We have several downtown squares. Originally we had four. Three are existing and they're each so different and individual and have such a different story. Brush Square is in the Southeast quadrant of downtown and it's right next to the convention center. And a lot of people lament that this square is what they might consider to have been junked up by buildings. I think that's fair, given that we are a city that lacks green space. But it is an interesting part of our city's history. Starting in the early 1930s, a group of civic leaders, women, wanted to save the O'Henry House. O'Henry actually only lived there for a very little period of time, but he was one of our most famous residents,eEspecially in the 1930s, if you can think about what a big deal it was to have this American short story writer with such a history in Austin.

And they worked with a professor at UT to move the O'Henry House about a block, two or three blocks away, from Fourth Street, I believe, to Fifth Street, kind of right there in the middle of the block. And it became really one of the city's very first history museum, if not the first history museum. Just a couple of years later, the city built Fire Station Number One, a very beautiful deco fire station right there on the corner. And then it was many, many years later that the Hilton Hotel Convention Center was being constructed. In that demolition, they discovered during demolition of an old iron works barbeque, a pit barbeque, they discovered a log cabin kind of a structure. Not really log, but wooden frame building inside.

And through tons of research they were able to determine that it was the surviving house of Susanna Dickinson and her husband. Of course, she being the only anglo survivor of the Alamo. And there was several years of wringing of hands and gnashing of teeth about what to do with this. And the Hilton was thinking they would incorporate it into their lobby and then people didn't want that. So eventually it was moved right across the street to Brush Square. I think it was 2003 that it was moved or so, 2003, 2005, and it was open many years later after it was rehabilitated. And so now we have these Brush Square museums and we're working to kind of tell the story of these little buildings and how they came to come to Brush Square. So this is a master plan that's currently being implemented.

Republic Square is one of the better-known urban parks in Austin. A lot of people know it for the home of our farmer's market. What many people don't realize is that it's early life was really at the heart of our Mexican American community. Our Lady of Guadalupe church was sited just right there. There was also a chili factory called Walker Chili Factory that employed many of the people that lived in this area right around Republic Square, and again, this is the Southwest quadrant of our city, really close to City Hall and Austin City Limits and all of that. And it was through a variety of forces, including our 1928 master plan and a lot of institutional racism and segregation that really pushed this community to the east side of town over time.

There was about a 20-year period that you'll see that the site was paved over. You'll see these gorgeous trees, which are actually called the Auction Oaks. In 1839, when our city was founded, it was under these oak trees that our city's first lots were auctioned off. So they're called the Auction Oaks. And so they were sort of paved over with concrete for many years. And it wasn't until the 1970s during our bicentennial that there was a sense of renewal and urban kind of a sense of civic pride that the parking lot was removed and the park kind of came into its new wave.

We've had some great partnerships to rehabilitate this space and it now has quite a bit of interpretive panels, as well as statues of Mexican war heroes to better interpret the Mexican American history of this space. But a lot more can happen here in terms of programming to better interpret it.

Let's see here. One of our favorite spaces, and I know Charles will agree, is Wooldridge Square. This is the square that really retains the highest degree of historic integrity in terms of our downtown squares. All of our squares were not particularly sacrosanct when the city was platted in 1839. They were kind of misused and abused, and this one served as a landfill for some time. You'll notice it has a unique topography, which I'm sure lended itself quite well to a dump. But Mayor AP Wooldridge in about 1910, really inspired by the city beautiful movement, decided to renovate this space and rehabilitate this space. He was able to get Charles Page, a Texas architect, to construct this little neoclassical bandstand.

And this park really had a new life from about 1910 on. It's particularly known for being a place of political stump speeches. Not as much recently, but certainly from about the 19-teens through the 1950s or so. Governor Colquitt started this tradition by announcing his gubernatorial bid from this space, and we've had a number of quite famous Texas politicians, including Allan Shivers and Pat Neff and Dan Moody, Jim Ferguson and Pappy O'Daniel. LBJ launched his bid for Senate here in 1948, which was very exciting. I think something that we're probably the most proud of is that Booker T. Washington spoke here in 1911 and we've only recently worked with our partners to put an interpretive panel talking about that talk and how important it was.

It's especially important here because it's a site that very few people would recognize as having any kind of link to African American history in our city. But indeed, not only did Booker T. Washington speak there, but some of our city's original black churches were right across the street. So these are stories that are still needing to be told, and we're fortunate to have partners working to help us tell those stories.

I have a special interest in our municipal cemeteries. I was fortunate to lead our city's first master plan for our municipal cemeteries. We have five official municipal cemeteries, but we actually have two family cemeteries that are on park land. But I would like to add that a lot of municipal park systems are stewards for cemeteries, and for many of them they were very difficult to manage. In many cases, they are no longer active spaces that are being sold, so they can come across as really more of a burden as opposed to a revenue generating site. We were able to really get our community to understand what an incredible opportunity these sites present to tell our city's history, and how they can be new spaces for green space, reflective space.We have over 150 acres of cemetery space within our city, and when you think about how large that is in terms of green space and our opportunities to activate it.

Kim McKnight

We have incredible cemeteries that are almost predominantly, completely African American, there's Evergreen and Plummers. And we have sections within some of the older municipal cemeteries that have segregated sections that were dedicated for people of color, whether that was African Americans, as well as Mexican Americans and others. I will say that it's been an interesting time with this chapel restoration. The chapel there was constructed in 1914. It's called the Oakwood Chapel, also designed by Charles Page. When we started this restoration, we knew that we were working to restore a 1914 chapel that was constructed in an 1839 cemetery, and it was constructed in this area of the cemetery that was historically known as the colored grounds.

Kim McKnight

And so, we did retain the services of an archeologist from the beginning to monitor all construction activities. And it was very disappointing to learn that indeed this chapel was built over numerous graves. We stopped construction when all of this was discovered, and engaged the community to discuss what had been found, talk about different options, share precedent cases. We're still in the middle of this. The chapel has indeed opened. We did exhume as many burials as possible and ended up exhuming about 37 graves. These individuals' remains were transferred to Texas State University and underwent a bio-archaeology analysis. And we've also had archeologists doing studies on some of the grave goods and burial hardware and things like that. We're literally in the midst of releasing those reports, hopefully within this spring, and working towards a reinternment, a public symposium to really just share the information that was found with the community and have different panelists there to talk. And we're going to be doing an exhibit that will be featured in the chapel about the reports and the people.

I'd be happy to answer more questions as I'm here over the next few days, but it's been kind of a heartbreaking but also interesting project. The silver lining is that it's really going to give us the information that we're hoping to have to better interpret this section of the cemetery, which has really never been done. People come out and they see a field of scant grave markers and don't realize that there's numerous burials, just lacking gravestones. And so we see this as an opportunity to do the research and to develop an interpretive plan for this section of the cemetery.

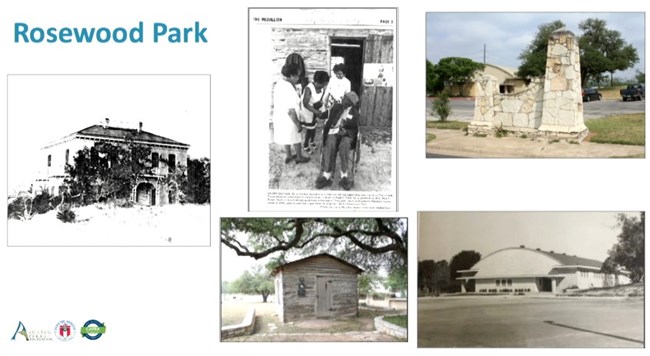

I'll just jump on a few more because I don't want to take away from my co-speakers' time, but there's so many other interesting parks that we're just now getting started with. Rosewood Park is a really interesting site. It's over 10 acres in size, I believe. It started after a 1928 city plan, which really recommended that the city offer services almost exclusively for African Americans, and Mexican-Americans. It wasn't as explicit, but that was assumed in East Austin as a way of managing the separate but equal policies at that time in our very Jim Crow era in Austin. And services were denied to people that were living kind of outside of this East Austin area. Streets weren't paved, utilities weren't extended.

The city did purchase land to create the city's first public park for the African American community, as well as land for their first Mexican American park, which was called Parque Zaragoza. Rosewood had 1870's, '80s estate, the Bertram Huppertz homestead, which is to the left, which was converted into… It was really a 1930s rec center. So, you've got an 1870s homestead that has this 1930s era rehab.

And over time, the park has got so many interesting layers. You've got the recreation center, you have a pool that was constructed shortly thereafter. We have a 19-early-40s USO auditorium. It was dedicated as the Doris Miller Auditorium in the 19… I'm not sure exactly when it was officially dedicated, but it was for African American service members. We have a 1970s cabin called the Henry Madison Log Cabin that was relocated here in the early '70s that was the home of Austin's first African American alderman in the 1870s during reconstruction.

So, the era of reconstruction is very poorly known and not talked about in Texas, and we think this is an opportunity to talk about the fact that we had black legislators, black alderman. There was a period immediately after the Civil War where there was a lot of leadership by that community before the Jim Crow era really took kind of a death grip over the South and you know you wouldn't see an African American in office in Austin for a century later.

So this is a really interesting cultural landscape to talk about and some of you might be familiar with this. But before I came to this city, I studied this, in one of Michael's [Holleran] classes, actually. This is a really good example of a contested landscape. The Elisabet Ney Museum was constructed, the first part was constructed in 1892 by some German masons that were hired by this German sculptor, Elisabet Ney. She was a really interesting artist who had a very illustrious career in Germany as a court sculpture and moved to the United States in search of a utopian life. And ended up in Georgia and eventually ended up in Hempstead, Texas, where she and her husband farmed for two decades and raised a son.

And she came out of retirement in the early 1890s. People kind of figured out who she was and they talked her into developing sculptures for the Colombian World's Exposition in Chicago, which was happening in the early 1890s. And so she was specifically hired to make sculptures of Sam Houston and Stephen F. Austin. And so she built a studio in Austin to do this work, and the first portion was built in 1892 and then the tower section was added about 10 years later. She died in 1907, and in about 1911 the site really became a museum. It was a group of women, created the Texas Fine Arts Association, which was really one of the first, if not, I'm careful with those superlatives, but very early arts organization in Texas. And from that point on, it really became an art museum devoted to the life of Elisabet Ney.

And that group went on to do amazing things, including starting the contemporary… which was then called Austin Museum of Art, but really started the first art museum scene in our city. Now, the city at one point decided to do a restoration master plan and got a grant through Save America's Treasures through the National Parks Service, and hired a firm, which is a very good firm and I'm not going to malign them at all. But they decided to undertake a very strict restoration approach to the landscape in addition to the building. And the recommendations that they came up with really ran counter to the community use of this site. So the community, there was no prairie, that's a new intervention. But over time, you have these beautiful oak trees. You had just really park land that people would come and picnic under. The community really used this space. It's a whole entire city block and it was really seen as kind of a community space.

The city and the museum director really saw this as an international art museum and wanted to really elevate this site. And so the plan, in terms of the landscape, really called to rebuild the chicken wire fence all the way around the perimeter of the property, taking down the 1939 violet crown historic wall. And it became a battle royale like none you've ever seen, between the community that really enjoyed this space, between the professional historic preservation people that knew what needed to happen here. It was a battle between preservationists, I think some traditional sort of viewpoints that felt that landscape restoration was well documented and a valid perspective in this site, and other sort of new waves of preservationists that felt like a cultural landscape approach was much more appropriate for this site.

So, the department kind of stood down and didn't tear down that wall, did put in the prairie restoration. But we're now at a point where we're going to be revisiting that entire plan to understand how we can shift the approach to better reflect what the community's needs are in the programming of the site. Because just how we program the site, bringing in contemporary art, temporary pieces, is not really compatible with the restoration plan that we had put forward. So we're pretty excited about that.

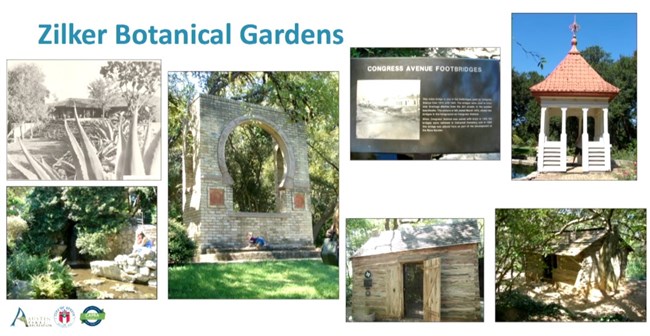

This is another area that I think is kind of interesting for preservationists. So we have this really lovely Zilker Botanical Garden that is really very much a vernacular landscape and that it was started by garden clubs. It was not a formal landscape architect designed space like Fort Worth had. It was a collection of garden clubs, like every garden club you could possibly think of. The African Violet Society, the rose people, the bonsai people, all the different people. And they advocated for about 10 years starting in the '40s to have a dedicated space within Zilker park. And they were given a very craggy, not particularly hospitable part of the park in which to construct botanical gardens.

They set forth to start developing gardens, and you see the early plans. There was a biblical garden, there were all sorts of really interesting gardens. And they also started to use this site as a repository for places within Austin and pieces and artifacts that needed homes. And so some examples of that are different log cabins that were brought in. So the Esperanza school cabin was one of the first one room school log cabins in Austin. It was at Spicewood Springs Road and Mopac, and as highway expansion is happening, this little log cabin needed a home. So it was moved in, in the late '60s to this space.

The Swedish log cabin actually was constructed in Govalle, which was a Swedish enclave in East Austin. It was first moved out to Round Rock to a heritage park, and then later the Swedish Pioneers Association worked with the city to bring it to the Zilker Botanical Gardens. There were a couple of buildings that were demolished during this time and there were pieces of those buildings that were placed into the landscape as these sort of follies. So the Bickler cupola on the far upper right is one of those. It was the cupola at the top of a building, the Bickler school, one of the earliest schools in Austin. We had the Butler window, which was from a very beautiful Victorian/neogothic home that was right across near Wooldridge Square, and was demolished much to the sadness of preservationists, but they saved this very iconic window and placed it within the feature. You see a lot of wedding photos done there.

The Congress Avenue foot bridges were the little metal foot bridges that would span between the road and the sidewalk on Congress Avenue because you had these sort of open sewers along the side. And these were brought over and incorporated into the landscape. We have streetlights from Lavaca that were along Lavaca Street from the like 1920s through the 1970s that were placed all through the parking lot. And then we have other gardens. We have rose gardens, we have a prehistoric garden that was a later addition in the '80s.

One of the really interesting gardens is the Taniguchi Japanese Garden, which is about a three acre site. Isamu Taniguchi was a Japanese man who was interned at Crystal City, Texas during World War II, was released, and at some point, in the '60s he found his way to Austin. His son, Alan Taniguchi, was the Dean of the School of Architecture at UT, and he worked with the city of Austin over the course of about 18 months with just one assistant to construct this gorgeous garden. And he called it an oriental garden because he was still very concerned about animosity towards the Japanese post World War II. And this is a site that has been in the garden. So when the National Register nomination for this park was done in the 1990s, the Zilker Botanical Gardens as a site really was not eligible by virtue of 50 year cut-off. There's also a great garden center I didn't go into from the 1950s, which is up there on the left. Sorry, early '60s.

But the traditional approach to this landscape would have been to look at those cabins and say, "Well, they're non-contributing because they were moved onto the site." But that's silly because these cabins that were moved into this space and have been in this site for more than 50 years, and it really is kind of its own sort of design landscape. And so this is important from a regulatory standpoint. They're about to expand South Mopac, and as you have architectural historians working for TexDOT, trying to determine what's significant and what's not. And I have to make cases for why the Zilker Botanical Gardens as a site is really the entire place is significant and we can't look at it as these individual parts, that it's really this collection. And I'm unfortunate to have Greg Smith with the National Register Program in Texas, and Sarah, my colleague, are working to update that nomination to add this site and so many others, so that we can better reflect how you need to be thinking about these places.

And many of you have these houses. Another one we have is Symphony Square, which is the 1970s urban renewal project with three buildings that were brought in and one that was already existing. We really need to think about how those types of sites that were really created as a result of suburbanization, highway expansion, urban renewal, are now in and of themselves eligible for the National Register, worthy of consideration of listing, and certainly cultural landscape.

Kim McKnight

Speaker Biography

Kim McKnight is an Environmental Conservation Program Manager for Austin’s Parks and Recreation Department. She manages the Historic Preservation and Heritage Tourism Program, which entails preservation planning, management and promotion of the historic resources of Austin’s park system.

Recent projects include the Seaholm Waterfront Redevelopment, the historic Brush Square Master Plan, and the Historic Cemeteries Master Plan. Her team maintains the inventory of historic resources in the park system, works with community groups on park improvements, and advises on issues related historic properties and cultural landscapes.

Ms. McKnight previously served as the executive director of the Texas Downtown Association, a statewide nonprofit organization with over 400 members. She also led the Texas Main Street Center of the Texas Historical Commission, which provides direct, on-site assistance to more than 80 Texas Main Street Cities in the areas of design, economic development, board development and strategic planning, visual merchandising, and interior space planning.

Ms. McKnight, a native Austinite, holds a Master of Science in Historic Preservation and a Bachelor of Arts in English from the University of Texas at Austin. Ms. McKnight enjoys bird watching, Texas dancehalls and peace on earth.

Tags

- kim mcknight

- ncptt

- landscape architecture

- austin

- texas

- parks and recreation

- brush square

- o'henry house

- republic square

- wooldridge square

- african american history

- evergreen cemetery

- plummers cemetery

- oakwood chapel

- rosewood park

- symphony square

- segregation

- cemetery

- texas fine arts association

- save americas treasures

- historic landscapes

- cultural landscapes