Last updated: January 22, 2024

Article

Charlestown Navy Yard: Chain Forge

Big Barney, Mighty Monarch, Little Andy, and Old Harry

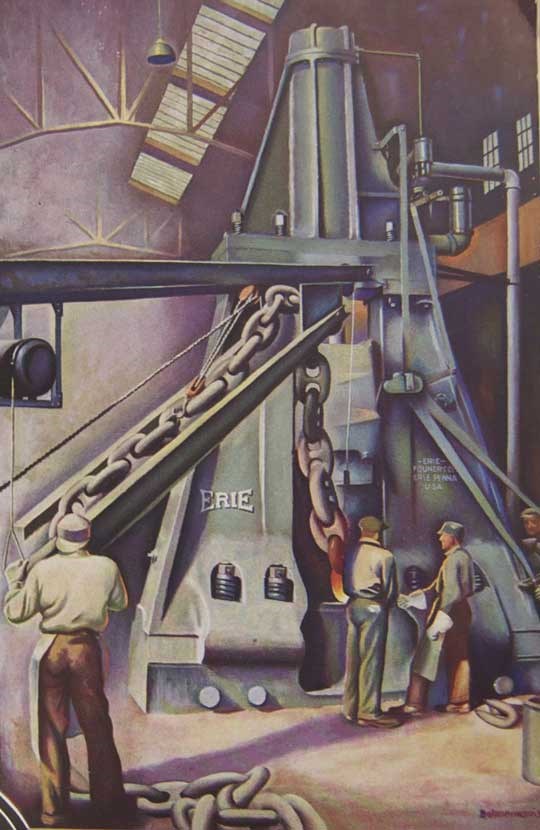

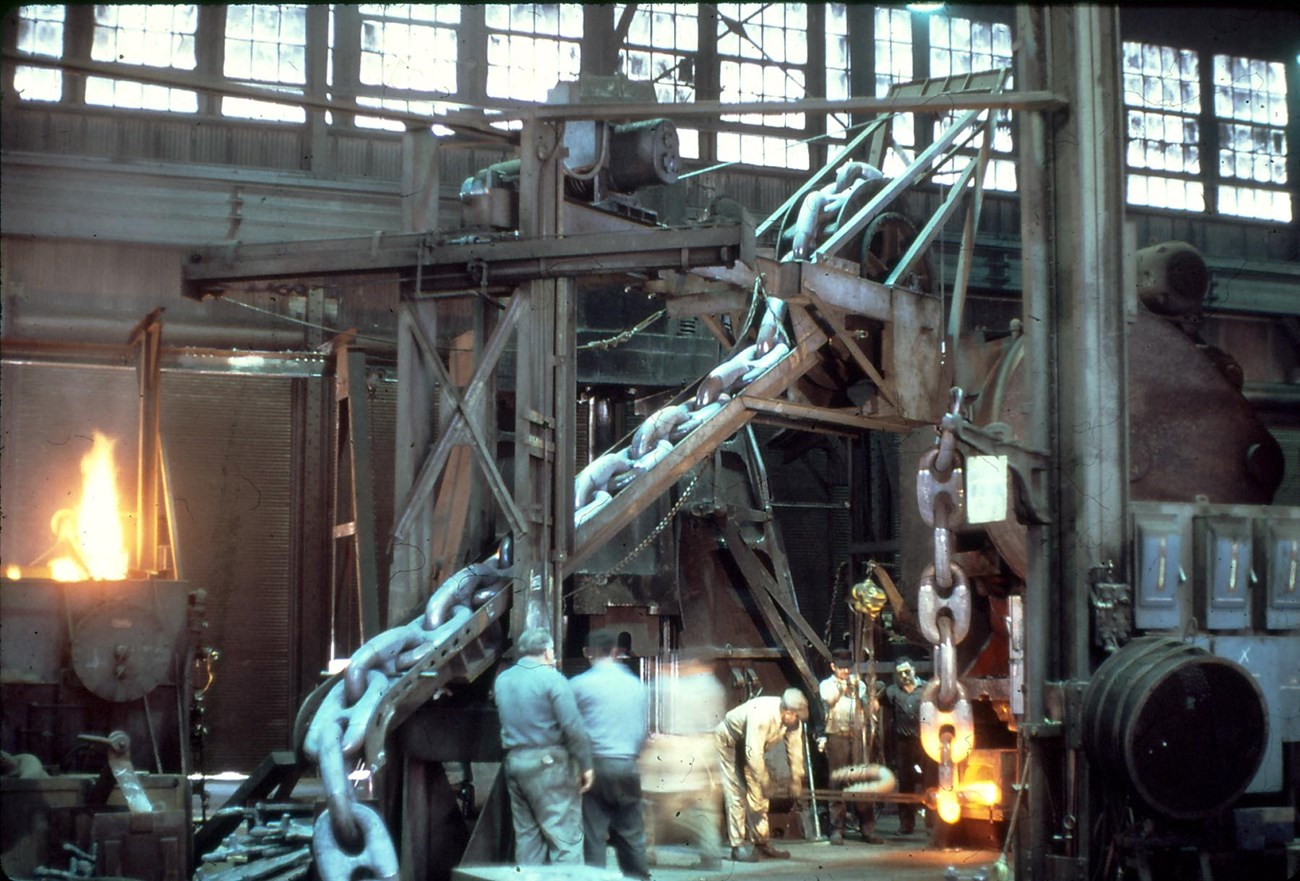

The workers named all the large drop hammers in Building 105, also known as the chain forge. Just like a blacksmith with a hammer, the drop hammers in the forge pounded heated metal into shape—except Big Barney, Old Harry, Little Andy, and the Mighty Monarch weighed up to 25,000 pounds. Powered by steam, workers used these machines to forge finished pieces much larger than possible by hand. Most notably, workers used the forges as part of the manufacturing lines for anchor chains.

Boston National Historical Park, BOSTS 9643-105-9a

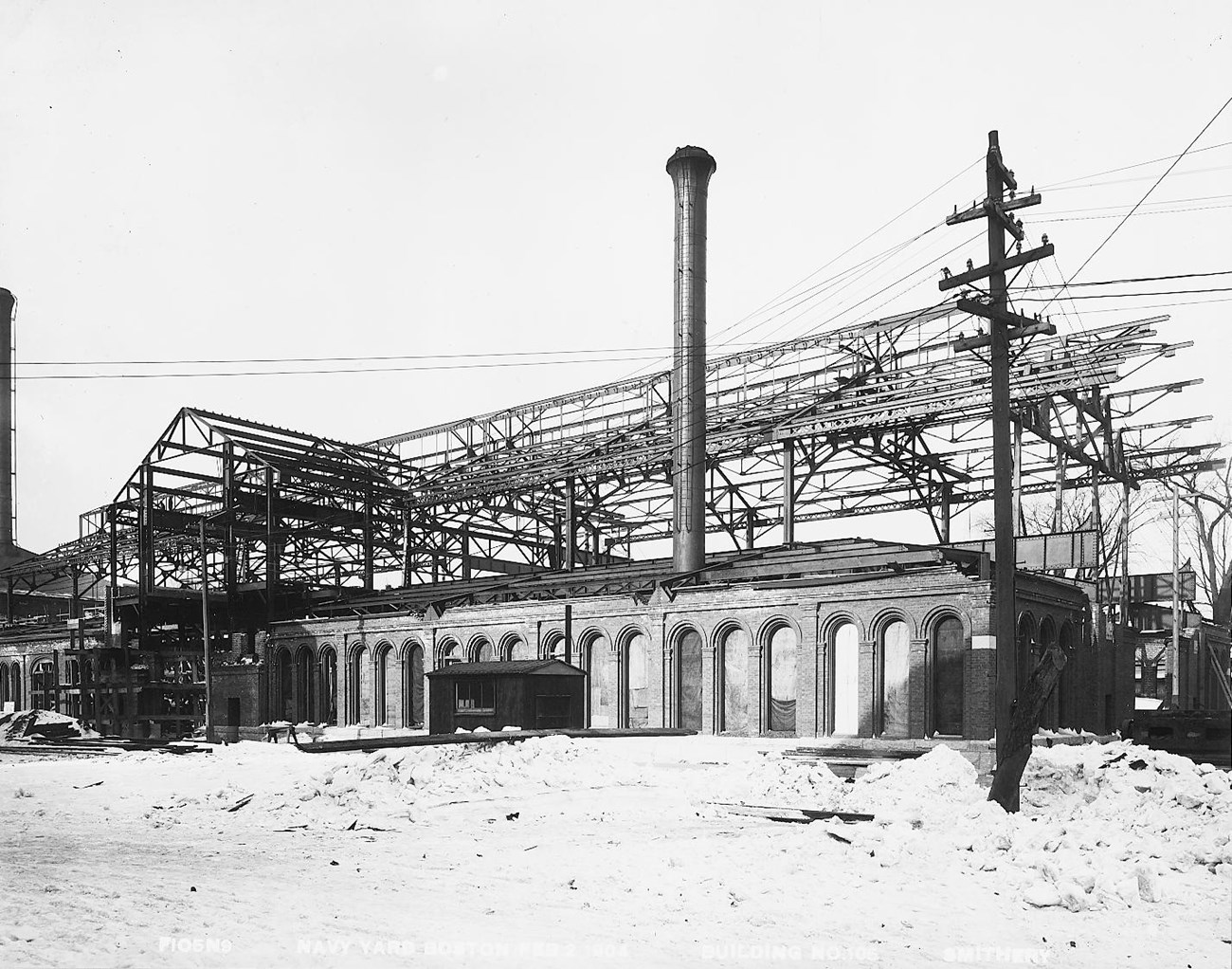

Completed in 1904, Building 105 was far from the first metal working shop at the Charlestown Navy Yard. In fact, by the 1880s, the Charlestown Navy Yard had already established itself as the primary manufacturer of anchors and anchor chain for the US Navy. This new building was designed to keep pace with the radically increasing size and number of Navy ships during the 1900s. Built not only large enough for heavy equipment like the drop forges, Building 105 also contained its own steam boilers and electric power plant. For a short time, the power plant generated electricity for other portions of the Yard, including new cranes and dry dock pumps. The power plant performed this role until the electricity needs of the yard exceeded Building 105’s output.

Despite its size and modernity, Building 105's output remained limited because the chain-making process of the era proved very slow. While ships were made of steel, anchor chain was made from wrought iron and involved welding each link by hand. During World War I, the rapid expansion of the Navy and the need to outfit each new ship with an anchor chain far outstripped the capacity of the forge. With this need, the Navy sought to develop a new chain-making process.

Cast chains, made by pouring molten steel into a mold, proved stronger, faster, and cheaper than wrought iron links. Adopted as the new standard in 1921, cast chain almost put Building 105 out of business. Set up primarily as a forge, Building 105 lacked much of the specialized equipment needed for casting parts, and the Navy decided against converting the shop to make the new chain links.

Boston National Historical Park, BOSTS 10103-1181

When all you have is a hammer

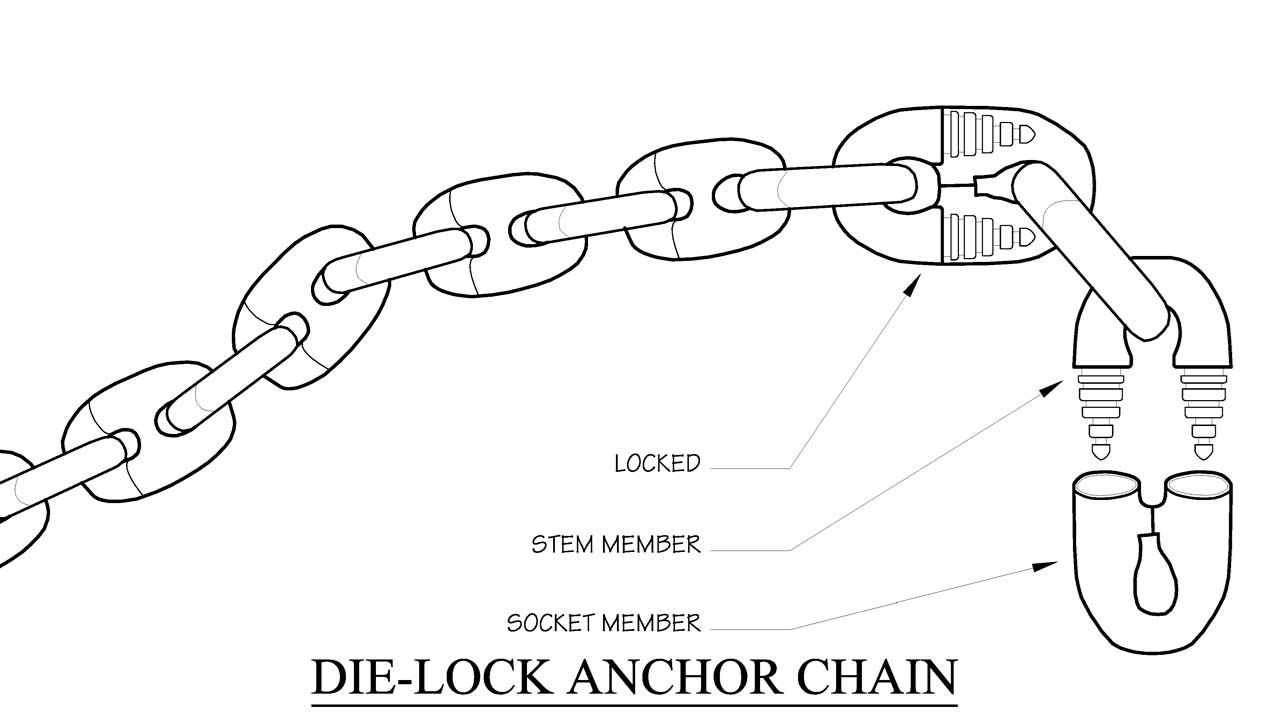

With the chain forge facing obsolescence in the 1920s, Master Blacksmith Albert Leahy, Leading Blacksmith James Reid, and Mechanical Engineer Carlton G. Lutts set out to develop a new type of chain using the drop hammers and forging equipment already available in Building 105. The resulting steel “die-lock” links were much stronger and faster to produce than wrought iron chain. In fact, the new chain also proved stronger than cast chain.

Formed from two interlocking pieces, the die-lock chain required no welding. Instead, one side had a toothed peg, or “stem” and the other had a closely sized hole, or “socket.” Using a furnace, workers heated the side with the socket member to 2,100 degrees Fahrenheit, allowing the metal to expand just enough for the cool stem member to be inserted into the sockets. The forge hammers then dropped several times with immense force to permanently bond the two parts together into a link of chain.

From title page of Historic American Engineering Record report on the Chain Forge, 2013

First used on a ship in 1926, the die-lock chain was adopted as the new standard for the entire United States fleet in 1928. The Charlestown Navy Yard reemerged as the Navy’s primary chain manufacturer leading into World War II. So many orders flooded into the Charlestown Navy Yard for chain during the war that the Navy contracted out much of the smaller sized chain production to private companies. Yet when it came to major warships, nearly every aircraft carrier, battleship, and cruiser used chain made in Building 105. And nearly every US Navy aircraft carrier since the end of World War II carried anchor chain made at the Charlestown Navy Yard.

Trade Literature at the American History Museum Library

The four and three quarter inch chain

Anchor chain is not measured by the width of the link. Rather, it is measured by the thickness of the metal rod used to make that link. Thus, the 4 ¾ inch anchor chain, the largest produced in Building 105, is not 4 ¾ inches long as the name would indicate. Instead every single link is 4 ¾ inches thick and weighs 360 pounds. This makes it suitable for use on the largest vessels afloat. These huge links were developed in the 1950s for the new Forrestal-class of “supercarriers” then being constructed.

By this time, the US government was trying to limit which industries in which it directly competed. Congress looked at closing both the ropewalk and chain forge at the Charlestown Yard. But when no private company bid on the contract for these large anchor chains, the responsibility fell to the workers in Building 105.

Larger and larger chains required bigger and bigger equipment. To build the 4 ¾ inch chain, Building 105 required significant renovations. In 1952, the Navy installed Monarch, the 25,000-pound drop hammer needed to shape these large chain links. At the same time, the Navy finally removed the last of the dirt floor in the shop. A holdover from traditional black smithing, a dirt floor helps alleviate exhaustion while hammering on an anvil in the heat of a forge. It was paved over, however, to allow crews to drive forklifts throughout the shop and ease their ability to move the heavier pieces they forged.

It was during these renovations that the Navy finally installed a larger ventilation system. Before, the shop often filled with smoke, and on summer days it easily broke 100 degrees, making conditions unbearable in the afternoon.

Boston National Historical Park, BOSTS 15908-18

Lasting Impact

The forge here in Charlestown remains the only place in the world that has made a 4 ¾ inch die-lock chain. When the Navy closed the yard in 1974, it did so with no replacement source for this large chain. Instead, the Navy chose to reuse the vintage, Charlestown-made chains.

When an old carrier was decommissioned, its chains were transferred to a new carrier. The same die-lock chains made in Building 105 can still be found on Nimitz-class aircraft carriers. Despite ceasing manufacturing in the 1970s, the die-lock remains in service on some of the largest ships in the US Naval fleet some 50 years later. The die-lock chain serves as a testament to the engineering and quality work undertaken by the workers of the Charlestown Navy Yard chain forge.

Sources

Carolan, Jane, Charissa Durst and Roy Hampton. Historical Structure Report for Chain Forge (Building 105), 2012.

“Gloom is Heavy at Boston Navy Yard.” New York Times, April 23, 1973. Accessed December 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/1973/04/23/archives/gloom-is-heavy-at-boston-navy-yard-many-fear-a-new-job-will-be-very.html

HAER No. MA-90-3

Ivas, Paul, Interview by Peter Steele and Arsen Charles, August 29, 1978, in Charlestown, Massachusetts. Transcript. National Park Service, Boston National Historical Park.

National Park Service, Boston National Historical Park. "National Register of Historic Places Inventory, Charlestown Navy Yard Nomination Form (1978)." In Boston National Historical Park, Charleston Navy Yard Boundary Enlargement Report. Denver: Denver Service Center, National Park Service, 1979.

National Research Council 1980. Anchor Chain for Future U.S. Vessels. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/19774.

Raber, Michael et al. Special Resource Study, Chain Forge Machinery in Building 105, 2014.