Last updated: December 7, 2021

Article

Changing Clothes

By the end of the 1930s, skirts were the common exemption to the standard uniform for women. As they ditched the breeches, they also lost their iconic Stetson hats. Women wanted more comfortable, better fitting, and more flattering uniforms. Many of the details of how changes came about are fuzzy, and it seems that the first separate women’s uniform adopted in 1941 was never implemented. However, the 1943 version of the uniform stuck. With it came the end of the unisex standard uniform.

The First Separate Women’s Uniform, Take 1

The NPS uniform was on the agenda at the January 21–29, 1941, National Park Service Conference. Although we don’t have minutes from the meetings, we know what recommendations came out of the conference. Two of them are important to the history of the women’s uniform. First, they suggested “that the whole matter of uniforms for Service personnel be studied by the Uniform Committee and a complete report thereon be submitted to the next Conference.” Second, they wanted to adopt a uniform for women employees.

The proposed women’s uniform was described as follows:

-

Cap: overseas type

-

Jacket: fitted; double breasted; side, patch pockets with bellows flap; torso length; bellows back

-

Shirt: steel gray color

-

Tie: regulation

-

Skirt: kick pleats, center front and back

-

Stockings: dark brown

-

Shoes: cordovan brown Oxford

It’s likely that the described women’s uniform was one of two options sent to the NPS in the spring of 1940 by Fechheimer Brothers Company, a uniform supplier at the time. Unfortunately, the drawings haven’t been found, and we don’t know exactly what their proposals were.

By itself, a proposed uniform is interesting but not conclusive. However, in August 1941 a summary of the actions taken on the conference’s recommendations was circulated. Regarding uniforms, it reports, “All of these recommendations have been incorporated in the National Park Service Uniform Regulations after being cleared with the Chairman of the Uniform Committee of the Conference.” In other words, the proposed uniform described above was, in fact, adopted as the first separate uniform for women in the NPS—six years earlier than previously thought.

The incomplete historical record increases the challenges associated with teasing out the chronology of NPS women’s uniforms. Understanding that, the lack of a specific surviving regulation can’t be used to refute other existing evidence from photographs and documents. The 1941 conference meeting summary and action report makes it clear that the uniform described above was “incorporated into the National Park Service Uniform Regulations” even if we don’t have a surviving copy of those regulations. Other sources, however, suggest that it might not have been that straightforward.

The 1941 summary and action report also called for the entire NPS uniform to be studied. As a result, a women’s uniform committee was established on October 20, 1941. Chaired by Jean McWhirt Pinkley, it included two women from Region III (Pinkley and Myra Appell) and two from Region I (Gertrude S. Cooper and Mariana D. Bagley). There were no representatives from Regions II and IV as there were no uniformed women in those regions at the time. To put that into context, there were zero women in uniformed positions in 19 western and midwestern states in 1941 (Colorado and Nevada had uniformed women only at some parks).

Given that their work began with the same stroke of the pen that approved the first separate women’s uniform, it wouldn’t be surprising if the committee revisited the just-approved women’s uniform as well. The specifications don’t appear to have been circulated to parks outside of the written conference summary. That’s unsurprising, however, given that the committee started its work just two months after the action items were distributed and just over a month before the United States entered World War II

In spite of this, there is some tantalizing evidence to suggest that some of the 1941 specifications were implemented. It’s unlikely that the double-breasted jacket—the item that was the biggest break with tradition—was ever manufactured. Certainly, no photographs of it have been found. Yet, on March 10, 1943, Fechheimer Brothers Company responded to a letter from Sallie Pierce Brewer noting that they provided NPS women employees “regulation uniform garments.” In an echo of the 1941 specification, they detailed a skirt with “a kick plate front and rear.” In the same letter, the note that “some of the ladies have worn the regulation Stetson hat, others an Overseas cap, the latter probably being more acceptable.” In later correspondence, Brewer refers to it as a “soft Stetson,” which suggests something more akin to some of the hats worn by women at Carlsbad Caverns than to the Stetsons worn by men rangers. In a reply letter on March 19, 1943, Brewer referred to the “former pleated skirt,” which further hints that a change took place. Photographs of temporary rangers Ethen Meinzer and Clara Ann Lausten document that they wore the overseas cap. Such photos and correspondence hint at missing uniform regulations from the 1930s or early 1940s.

For his part, NPS Uniform Committee Chairman John C. Preston summed it up his understanding of the women’s uniform on March 9, 1943, writing, “Although existing National Park Service uniform regulations provide for a women’s uniform, a standard style has never been determined. During 1941 and the early part of 1942, our Women’s Uniform Committee, under the chairmanship of Mrs. Jean McWhirt Pinkley, devoted considerable time to the study of this matter. No final recommendations were ever reached by the Women’s Uniform Committee because it was determined by the Director’s Office that it would be useless to continue the study in view of War Conditions.”

Tightening Their Belts

As World War II raged, shortages on the home front included difficulties acquiring fabrics. Guides at Carlsbad Caverns undoubtedly made their existing uniforms last as long as possible. However, some women received war appointments or were Substitute Rangers and would have needed new uniforms. By 1943, acquiring cheaper uniforms for men and women working as temporary rangers during the war was a hot topic in the NPS.

On April 2, 1943, Preston wrote to Flechheimer Brothers Company observing, “It seems quite likely that some of our temporary ranger positions in parks this summer will be filled by young women.” He suggested that the company include pricing for skirts possibly patterned after the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) style, made of regular NPS uniform material and other fabrics. Although he acknowledged that men and women could wear the same style of jacket, he asked, “Can you furnish an overseas cap? If it is not possible to manufacture skirts because of limited demand would you be willing to sell the fabric by the yard?”

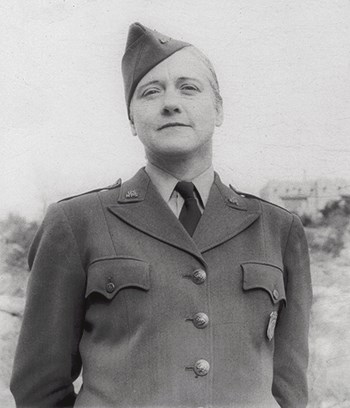

It’s not documented why Preston seized on the WAAC uniforms, but they were certainly popular and patriotic at the time. In 1943 women designers updated the corps uniforms. The new tailored designs were considered among the best in the women’s forces. It’s not surprising then that the NPS would want to copy the stylish look.

Fechheimer Brothers’ April 26 response to Preston included fabric samples as well as quotations for jackets and trousers for men and jackets, skirts, and overseas caps for women. Taking their cue from Preston, they proposed a waist-length fatigue jacket to be worn by both men and women. The women’s skirt was described as “a six-gore skirt without pleats, although this skirt can be made with pleats at slight additional cost if desired.” Gores are the triangular pieces of fabric that are wider at the bottom and narrow at the top, sewn together to make an A-line skirt.

The “minimum uniform requirement” and cheaper fabrics were approved for the 1943 season, but women quickly found that they had another coat option besides the unflattering fatigue jacket.

The First Separate Women’s Uniform, Take 2

On May 15, 1943, Preston, who in addition to being the chairman of the NPS Uniform Committee was superintendent of Mount Rainier National Park, shared with the NPS regional directors his proposed uniform for the two women rangers he had hired for that summer. The uniform consisted of:

-

Coat: 16 oz. elastique “WAAC” type

-

Skirt: 16 oz. elastique, gores and 4 pleats

-

Hat: 16 oz. elastique overseas cap

-

Shirt: steel gray poplin with shoulder straps and pleated pockets

-

Necktie: four-in-hand, “Barathea” [a type of fabric], dark green

-

Shoes: Oxfords, cordovan color, plain toe

-

Belt: NPS hat band with buckle added

He noted that the WAAC coat (also called a blouse) “would be much more practical than a jacket, as the uniform may then be worn later as a two-piece suit.” Although Preston didn’t note it, the WAAC-style uniform coat eliminated the boxy look of the standard uniform coat through tailoring and changing the pockets that were so unflattering for many women. The false upper pockets (flaps only) were also more appropriate for a woman’s figure, and the lower welt pockets instead of the bellow pockets reduced bulk at the hips.

On May 25, 1943, Acting NPS Director Hillory A. Tolson approved Preston’s women’s uniform “for the 1943 season on an experimental basis.” He also approved the use of lighter weight standard uniform materials where appropriate for the local climate.

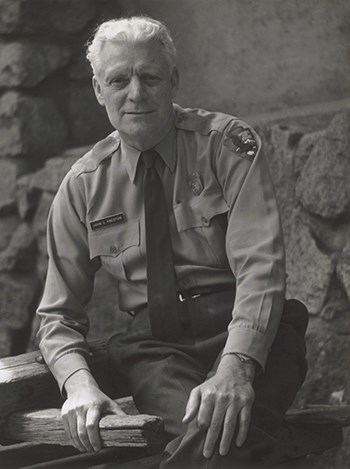

Following Tolson’s approval, Preston had a photograph made (shown at left) of Rangers Brunes and Dickenson in their uniforms to share with other parks. As word of an approved women’s uniform reached other parks, Brewer and other women ordered the WAAC-style jacket. However, women who worked in warmer, sunnier climates complained that the overseas cap was impractical for their circumstances as it offered no shade. Although “experimental,” the 1943 was another officially sanctioned women’s uniform. This one, however, had more staying power.

Stitching Up the Details

Although we haven’t found documents that formally adopt the 1943 “experimental uniform” as the official women’s uniform, it clearly was. We know that a 1947 amendment to the Administrative Manual was issued but the text of it has not been found to date. Traditionally, when NPS handbooks are updated, only the affected sections are sent out to the field. Park staff take out the old pages and insert the updated replacements. While this is environmentally friendly and cost effective, destroying the old pages creates historical gaps in surviving copies that can lead to confusion. We don’t know what the 1947 regulations said because it was amended over time and previous versions were destroyed, per the instructions at the time. This probably also explain other “missing” regulations both before and after 1947.

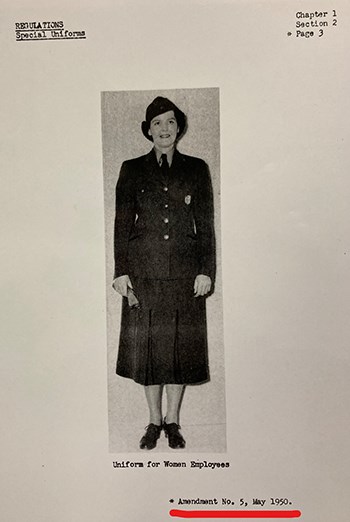

However, we do have a May 1950 photo from a later amendment and the continuity between it and the 1943 uniform is undeniable. In the 1950 photo, Carlsbad Caverns Guide Olive Johnson models the uniform to demonstrate the correct way to wear it. She wears the collared shirt (presumably gray), four-in-hand tie (presumably green), neutral hose, Oxford shoes, skirt, WAC-style jacket, and the overseas cap. (Note: The WAAC name was shortened to Women’s Auxiliary Corps, or WAC, in 1943.) She holds leather gloves in her right hand. There are a couple of differences with the 1943 uniform specifications that need to be clarified.

Although it’s difficult to tell given the quality of the photo in the regulations, Johnson’s skirt appears to be of an older, pleated design. It certainly doesn’t have the more flowing A-line of the skirts worn by Brunes and Dickenson in 1943. When Johnson began working as a guide at Carlsbad Caverns in 1943, many women there wore this type of skirt. It seems reasonable to assume, therefore, that she purchased a similar one because parks were supposed to be internally consistent for these types of choices. At the time, employees didn’t have to upgrade to new uniform styles until the items were no longer in serviceable condition. Of course, it’s possible that the missing 1947 amendment changed the skirt design, but it seems unlikely that the NPS would return to an older style.

Perhaps more suggestive of a specific modification to the 1943 uniform standard, Johnson’s WAC-style coat doesn’t have epaulettes on the shoulders. Jackets worn by Brunes and Dickerson in the 1943 photo clearly depict epaulettes, as does a 1951 photo of Viola Shannon, who also worked at Carlsbad Caverns. Shannon, who began work at the park in 1941, no doubt took care of her coat and got many years of service from it. If Johnson’s coat without the epaulettes is a later amendment, it wouldn’t have prevented Shannon from continuing to wear an earlier one as long as it was in good condition. There could be a similar explanation for the jacket with epaulettes worn by Mrs. Absalon at Morristown National Historical Park in 1954. The standard NPS uniform coat in 1947 didn’t have epaulettes either. Could this have been a modification to make the men and women’s coats look more similar? Or perhaps the uniform standard didn’t specify one way or another and there were more women’s jackets without them than we have documented in photos. Or Johnson could simply have had a local exemption to wear a jacket without epaulettes. Unless a copy of the 1947 amendment is found, this remains speculative.

Several different styles of overseas caps are worn in different historic photographs dating from 1942 to 1955. Given that prior specifications only listed “overseas caps,” it’s not surprising to see variation. One notable difference seen in the photos is that, unlike Brunes and Dickerson, most women wear the USNPS collar ornament on their caps. It’s possible that this was another change that appeared in the lost 1947 regulations. Because Johnson is wearing one in the May 1950 photo, it must have been part of approved uniform regulations (now lost). The gloves in Johnson’s hands may represent another addition to the uniform.

Based on our current understanding of the uniform regulations, supported by available photographs and documents, the 1943 “experimental uniform” became the first manufactured and widely accepted separate women’s uniform. This separate NPS women’s uniform was designed four years earlier than previously thought. Although small modifications may have been made in 1947, the overall look of the dress uniform remained the same from 1943 until about 1955.

Although we can’t pinpoint what modifications where made in 1947, one thing we know for sure is that by 1950, the women’s uniform was segregated from that of the men, placed under the heading “Special Uniforms” in the regulations. In the mid-1950s, women briefly gained authorization to wear the standard fatigue coat—only by then, it (like the rest of the NPS uniform) had become “the men’s uniform.”

Explore More!

To learn more about Women and the NPS Uniform, visit Dressing the Part: A Portfolio of Women's History in the NPS.