Last updated: August 12, 2021

Article

Castillo de San Marcos and Fort Matanzas National Monuments Cultural Landscapes

Carol Highsmith, Library of Congress.

Castillo de San Marcos and Fort Matanzas, both in present-day northeastern Florida, represent the best-preserved evidence of the Spanish Empire’s 287-year presence in southeastern North America. The oldest masonry fortification remaining in the continental United States, Castillo de San Marcos formed the core of a system of defenses built to protect St. Augustine, Florida, which was the first permanent European settlement in the continental United States. Fort Matanzas National Monument is located about 14 miles south of Castillo de San Marcos National Monument on Rattlesnake Island. The Spanish constructed Fort Matanzas between 1740 and 1742, designed as a series of towers along the Matanzas River from which soldiers watched for enemy ships entering the river that provided access to St. Augustine.

NPS

Landscape History

Spain constructed Castillo de San Marcos between 1672 and 1695, selecting the site based on its proximity to the Matanzas River and its harbor. It was built to defend St. Augustine, their main colonial outpost in southeastern North America, and to protect the important sea routes from the North American continent to Spain.The interaction between the Spanish missionaries and Native Americans had a devastating impact on the tribes, who did not have immunity to infectious diseases introduced by the Europeans. The Timucua in east Florida and Guale tribes along coastal Georgia were among the hardest hit. Through the hardships wrought by enslavement, conquest, and conversion, Native Americans from the Timucua, Guale and Apalachee (occupying the area of Florida between the Aucilla and Apalachicola Rivers) played a significant role in the history of the Spanish establishment of St. Augustine and the construction of Castillo de San Marcos. The Spanish utilized the labor of Native Americans, enslaved Africans, convicts, hired workers, and soldiers to construct the two defensive works and to grow food crops for settlement.

In 1825, the War Department changed the name of Castillo de San Marcos to Fort Marion and made various changes to the fort and landscape. Over the decades of managing the property, the War Department developed an appreciation for the fort’s historic significance and made efforts to preserve the building and its features. By the end of the nineteenth century, the less-used Fort Matanzas was in poor condition and its foundation had split into three sections, necessitating extensive repairs.

Historic Significance

For cultural landscapes such as Castillo de San Marcos National Monument and Fort Matanzas National Monument, documenting existing conditions and evaluating historic resources are critical in the development of a strategy for their management and treatment. Cultural landscape analysis involves two primary activities: evaluating historic significance and assessing historic integrity using criteria determined by the National Register of Historic Places.

NPS

Castillo de San Marcos National Monument

The National Register of Historic Places listing recognizes two periods of significance for Castillo de San Marcos. The first, 1672-1821, corresponds to the Colonial period which begins with construction and ends with the transfer of the fort to the United States. The second period, 1821-1924, represents the period when the property was under the administration of the U.S. War Department. Castillo de San Marcos, including the moat, covered way, glacis, and ravelin, are significant for their connections with military history and representation of efforts to protect Spanish interests in southeastern North America. It is also important for military engineering principles, standing as the oldest masonry fortification in the United States and representing theories and conventions of coastal defense during the periods of construction and development.The fort’s history is also notable for its association with Chief Osceola, who led the Seminole Nation against the U.S. Army during the Second Seminole War. Beginning in 1835, the U.S. Army pursued Osceola and his band of warriors as they withdrew to avoid capture. In October 1837, Osceola arrived under the flag of truce in St. Augustine to negotiate with American government officials. Osceola was seized and imprisoned at Castillo de San Marcos (then Fort Marion). In December 1837, the army sent Osceola to Fort Moultrie, near Charleston, South Carolina, where he died on January 30, 1838.

Fort Matanzas National Monument

The 1976 National Register of Historic Places listing for Fort Matanzas establishes a period of significance extending from 1500 to 1899. The timeframe spans events surrounding the Ribault Massacre of 1565, construction of Spanish outposts built to defend St. Augustine, and construction of the headquarters and visitors center.The site is associated with the 1565 Ribault Massacre that occurred within the area of what is now the park and comprises part of the sequence of events whereby Spain eliminated France from its competition for dominance in northern Florida. The Spanish learned that the Gulf Stream provided the most efficient return route to Spain. The control of shipping channels along this route, including those on the eastern coast of Florida,was critical to the expansion of Spanish influence.

In 1564, the French Huguenots established Fort Caroline in present-day Jacksonville, 60 miles north of what is now Fort Matanzas National Monument. Pedro Menéndez de Avilés was sent to defend Spanish interests in Florida and to remove this French threat. Jean Ribault arrived to resupply the French at Fort Caroline on the same day that Menéndez arrived in Florida. Menéndez and his men overtook Fort Caroline and massacred the French soldiers who had been shipwrecked and were marching back north to Fort Caroline. With the end of French occupation of the area, the Spanish established St. Augustine as their capital in Florida, and proceeded to construct wooden watchtowers along the Matanzas River.

Landscape Description

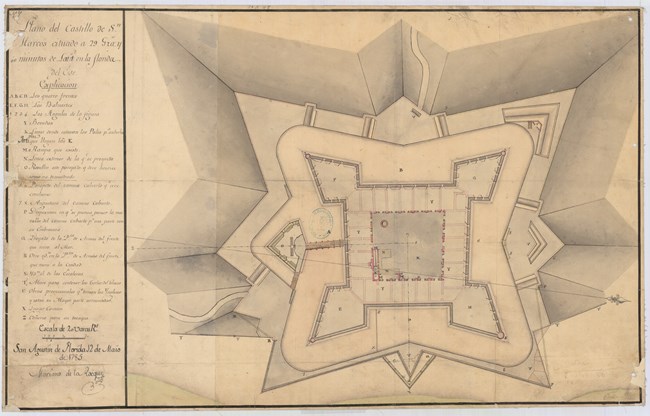

Castillo de San Marcos and its surrounding landscape reflect conventions of seventeenth-century military engineering, specifically the bastion system of fortification design. This style incorporated bastions from which to fire artillery and a series of earthworks outside the fort’s walls to keep invaders at a distance. Castillo de San Marcos is a symmetrical fortification with four corner bastions, curtain walls, multiple embrasures, a glacis, and a moat, among other features.

NPS

A seawall extends north and south from the water battery to hold back the waters of Matanzas Bay.Spain originally built a seawall adjacent to Castillo de San Marcos in the 1600s, but the United States Army Corps of Engineers largely rebuilt the seawall in the 1830s and 1840s using granite and coquina. The Army Corps of Engineers subsequently extended the seawall to the south and north, so today, the entire eastern boundary of the national monument includes a seawall. The covered way occupies the area beyond the moat, on the northern, western, and southern sides of the fort.

NPS

The presence of trees in the landscape is a character-defining feature of the War Department period of significance. Many of those trees became part of the landscape in the late 1800s and early 1900s. However, this aesthetic was very different than the military landscape during the Spanish Colonial period. Maintaining an open space filled with low-growing turf replicates the appearance of the landscape in the 1880s. The common turf species grown in Florida include Bahiagrass, Bermuda grass, Centipede grass, Seashore Paspalum, St. Augustine grass, and Zoysia grass, with Bermuda grass being the most appropriate choice for replicating the War Department period. More information would be needed to identify specific species grown around the fort during the Spanish colonial period.

NPS

Fort Matanzas features a thirty-foot-high observation deck, a terreplein, officer and soldiers’ quarters, and a powder magazine. The United States War Department and, later, the NPS, completed stabilization and restorations to the fort in the 1900s. A ferry service transports visitors to the fort from the visitor center across the Matanzas River. The built environment is incorporated into the site in a way that preserves most of the natural vegetation and utilizes the existing plant communities and individual plants for functional and educational purposes.

NPS

NPS

Landscape Preservation and the Cultural Landscape Report

As early as the 1830s, military officials recognized the historic significance of Castillo de San Marcos and attempted to repair broken and deteriorated features.The War Department oversaw a major stabilization of the Fort Matanzas in 1927, and in 1935 administration was transferred to the NPS. The NPS constructed a visitor center and ranger residence across the river from the historic fort and maintained the fort, made necessary repairs, and installed a seawall.

In 2020, the National Park Service produced a Cultural Landscape Report (CLR) for Castillo de San Marcos National Monument and Fort Matanzas National Monuments. This document helps to establish the historic significance of the landscape through an examination of the site history and existing conditions of the character-defining features of the two national monuments. It provides treatment recommendations that are intended to preserve historic resources while addressing issues related to the contemporary use of the site and helps to inform the decision-making process for site management, specifically around issues like visitor use, turf management, and resilience to natural hazards.

The main goals of treatment are to improve interpretation of the sites by preserving or rehabilitating the character-defining elements of the national monuments that were present during the period of significance. It also aims to improve the ability of the landscape to withstand pressures associated with steadily increasing visitation and its impact on vegetation and the circulation system at the national monuments.

Sections of this article were adapted from the 2020 Cultural Landscape Report for Castillo de San Marcos and Fort Matanzas National Monuments, prepared by WLA Studio and published by the National Park Service.

Explore the Landscape

Virtual Tour

Quick Facts

- Cultural Landscape Type: Historic Designed Landscape, Historic Site

- National Register Level of Significance: National

- National Register Significance Criteria: A, B, C

- Periods of Significance:

Landscape Links

- Castillo de San Marcos and Fort Matanzas: Cultural Landscape Repot (2020)

- National Register of Historic Places: Fort Matanzas National Monument

- National Register of Historic Places: Fort Matanzas National Monument Headquarters and Visitor Center

- National Register of Historic Places: Castillo de San Marcos National Monument

- Library of Congress: Castillo de San Marcos, Historic American Buildings Survey

- Library of Contress: Fort Matanzas, Historic American Buildings Survey

- More about NPS Cultural Landscapes

Tags

- castillo de san marcos national monument

- fort matanzas national monument

- profile

- cultural landscape

- ser

- castillo de san marcos

- fort matanzas

- fort

- seawall

- war department

- military

- engineering

- fortification

- bastion

- earthworks

- coquina

- rustic style

- architecture

- spanish colonial era

- masonry

- coastal defense

- chief osceola

- seminole

- landscape design

- fort marion

- turf

- historic preservation

- spotlight