Last updated: October 30, 2024

Article

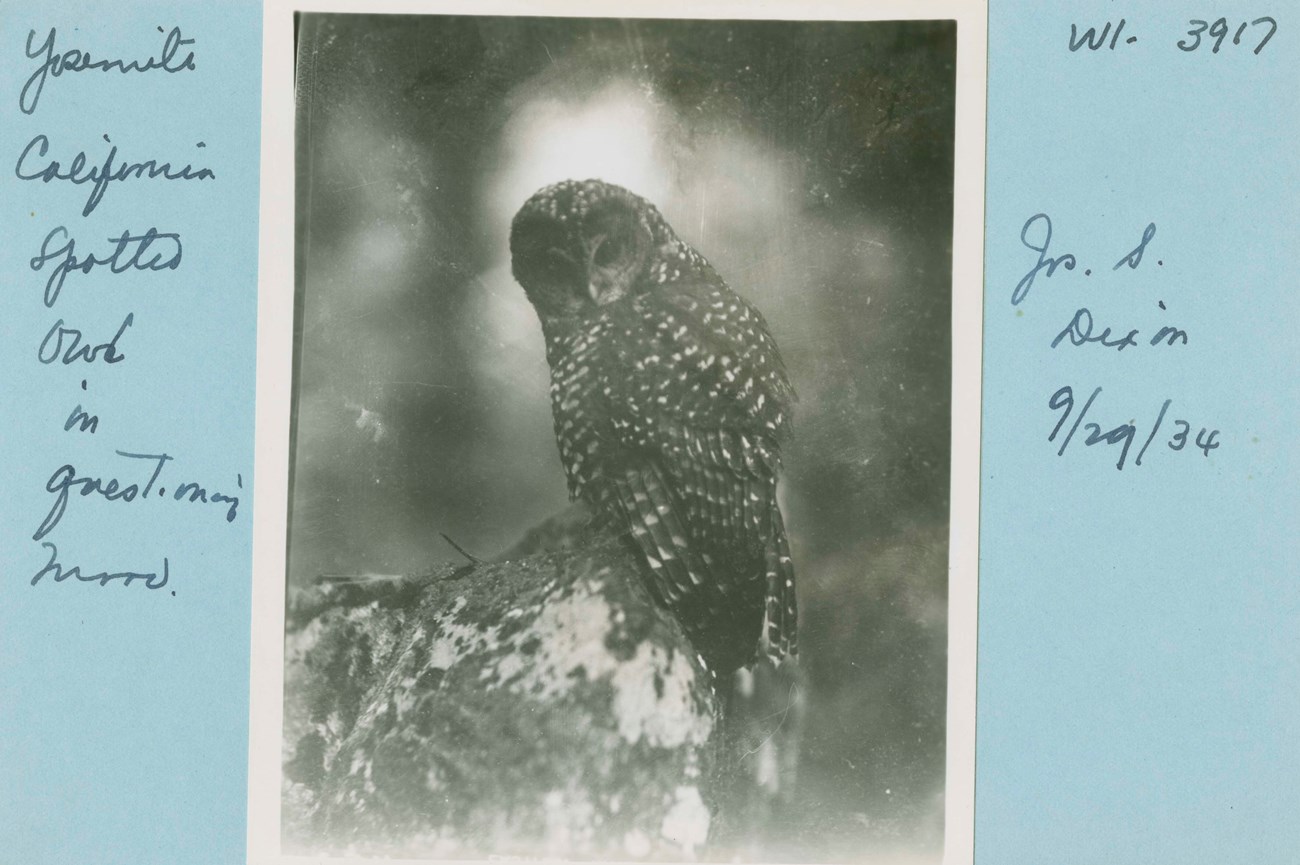

California Spotted Owl

Northern spotted owl (USFWS/John and Karen Hollingsworth), California spotted owl (USFWS/Rick Kuyper), Mexican spotted owl (USFWS/Shaula Hedwall).

General Description

The iconic spotted owl evokes images of the damp, dark Pacific Northwest. But did you know that this denizen of old-growth forest comes in three varieties, ranging across the western United States? The Pacific Northwest subspecies is the northern spotted owl (Strix occidentalis caurina) that lives in Washington, Oregon, and northern California. A southwestern subspecies, the Mexican spotted owl (Strix occidentalis lucida), occupies the forests and canyons of Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, and West Texas, south into Mexico. And a California subspecies, the California spotted owl (Strix occidentalis occidentalis), lives in the Sierra Nevada mountains and southern California coast mountain ranges.

Macauley Library, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, W. Scott Young, public domain.

All three subspecies are medium sized (46–48 cm, 18–19 in) chestnut to dark brown owls with white spots or blotches on much of their bodies. White and light brown bands bar their wing and tail feathers. Their round face is shaped like a disk to collect sound, with a whitish “X” pattern of feathers surrounding a yellow-green bill. Two characteristics that help distinguish spotted owls from other owls are their dark brown eyes (most owls have yellow eyes) and lack of ear tufts.

Distinguishing the three subspecies from each other is a little more difficult, though their ranges only overlap in northern California. Generally, the California spotted owl falls between the larger, darker northern spotted owl and the smaller, paler Mexican spotted owl in size and color.

A close cousin and competitor, the slightly larger barred owl (Strix varia), has dark vertical streaks on its abdomen instead of white spots, horizontal bars on its breast, and a brighter, yellow-orange bill. The barred owl also has a different call.

Habitat

Like its northern and Mexican spotted owl cousins, the California spotted owl nests in dense, shady forest with large, old trees and downed logs. The large trees offer natural cavities, large limbs, and broken tops for roosting and nesting, while the shady, multilayered canopy hides the nest and helps the owl stay cool. Wood on the forest floor shelters woodrats and other owl prey, while also growing the fungus that rodents love to eat. California spotted owls forage in this kind of mature forest but also in more open conditions, near forest edges and openings that support a wider variety of food.

Spotted owls generally do not migrate, though California spotted owls may move from nesting areas in mid-elevation conifer forests to lower elevations in winter, such as the foothill riparian and oak woodlands of the Sierra Nevada.

Diet and Foraging

Owl feathers are specially engineered for silent flight on the hunt. Turbulent air that causes the swooshing sound of flight is channeled at the front of an owl’s wing feather by comb-like serrations. The sound is further dampened as the air flows over the velvety soft layer covering each wing feather and exits through a soft fringe on the wing’s trailing edge. Add to this an owl’s keen eyesight and sharp hearing, thanks to a facial disk that funnels sound into its offset ear openings. These asymmetrical openings triangulate the subtle rustling sounds of a hapless woodrat. The nocturnal California spotted owl applies these talents to catch its favorite prey, primarily flying squirrels and woodrats. Mice, pocket gophers, birds (including screech owls!), lizards, and insects, like moths, are also on the menu. It forages in short flights from a perch to catch ground- or canopy-dwelling prey, swallowing its prey whole and regurgitating the undigestible bones and fur as a pellet. Owls will cache excess prey on moss-covered limbs, broken-off stumps, or on the ground under logs, tree hollows, or among moss-covered rocks.

Spotted owls themselves, especially eggs and young, fall prey to great-horned owls (Bubo virginianus), the common raven (Corvus corax), and the American goshawk (Accipiter atricapillus).

Behavior

Spotted owls are solitary outside of the breeding season, though they typically share the same home range with their long-term mate. In spring, nesting owls come together in monogamous pair bonds. They perch together and nibble at each other’s face, head, and neck feathers (allopreening) while softly cooing and chittering. Nesting season also brings out strong territoriality, with owls aggressively responding to the calls of other owls (whether real or imitated by humans).

Spotted owls fly through the forest in short gliding flights alternating with fast wingbeats. Their relatively large wings compared to body size helps them maneuver deftly through the trees after prey.

Reproduction

USFWS / Rick Kuyper

In mid-February, pairs start roosting together and courtship begins. The male brings gifts of food. Pairs call to each other at dusk and dawn. Like most owls, the California spotted owl doesn’t actually build a nest. It may adapt an old raptor nest, but typically finds a broken top or cavity in a large, old tree in which to lay its 1–4 white to pearl gray eggs. In the Sierra Nevada, nest trees average 124 cm (49 in) diameter at breast height and 31 m (103 ft) tall! One study found the average age of nest trees in the southern Sierra to be >227 years.

The female incubates her eggs for about a month until they hatch into downy, helpless (altricial) young that will stay in the nest for another 5 weeks. Nestlings often leave the nest early (“branchers”) to explore nearby tree limbs. They hop around, vigorously flapping their wings to begin the awkward business of learning to fly. Once launched, fledglings remain with their parents through summer but disperse soon after in search of a mate and their own territory.

Conservation

Joseph Dixon, public domain.

While its close cousins have long been listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act—the northern spotted owl in 1990 and the Mexican spotted owl in 1993—the California spotted owl was only recently proposed for listing, in 2023. The proposal makes separate recommendations for its two Distinct Population Segments: threatened for the Sierra Nevada population and endangered for the Southern-Coastal population. Historically, California spotted owl habitat was degraded and lost from past timber harvest practices in mature forest that reduced nesting trees, canopy cover, and downed logs. Currently, large-scale, high severity fire is increasingly destroying the owl’s nesting and foraging habitat. Compounding these threats is competition from the invasive barred owl, which is larger, more aggressive, and can hybridize with the California spotted owl as it expands southward into California.

Where to See

The California spotted owl occurs in Lassen Volcanic NP, at the northern edge of its range, as well as in Yosemite NP and Sequoia-Kings Canyon NP to the south. North and west of Lassen is the northern spotted owl’s range, which overlaps Whiskeytown NRA, Redwood NSP, Oregon Caves NMP, and Crater Lake NP.

Learn More

Spotted owl call:

https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Spotted_Owl/sounds

Barred owl call:

https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Barred_Owl/sounds

Reducing fire risk:

https://www.fws.gov/story/3-efforts-underway-support-california-spotted-owl-and-reduce-wildfire-risk

Download a pdf of this article.

Prepared by Sonya Daw

NPS Klamath Inventory & Monitoring Network

Southern Oregon University

1250 Siskiyou Blvd

Ashland, OR 97520

Featured Creature Edition: October 2024