Last updated: July 25, 2024

Article

Big Gun Shoot

Naval History and Heritage Command

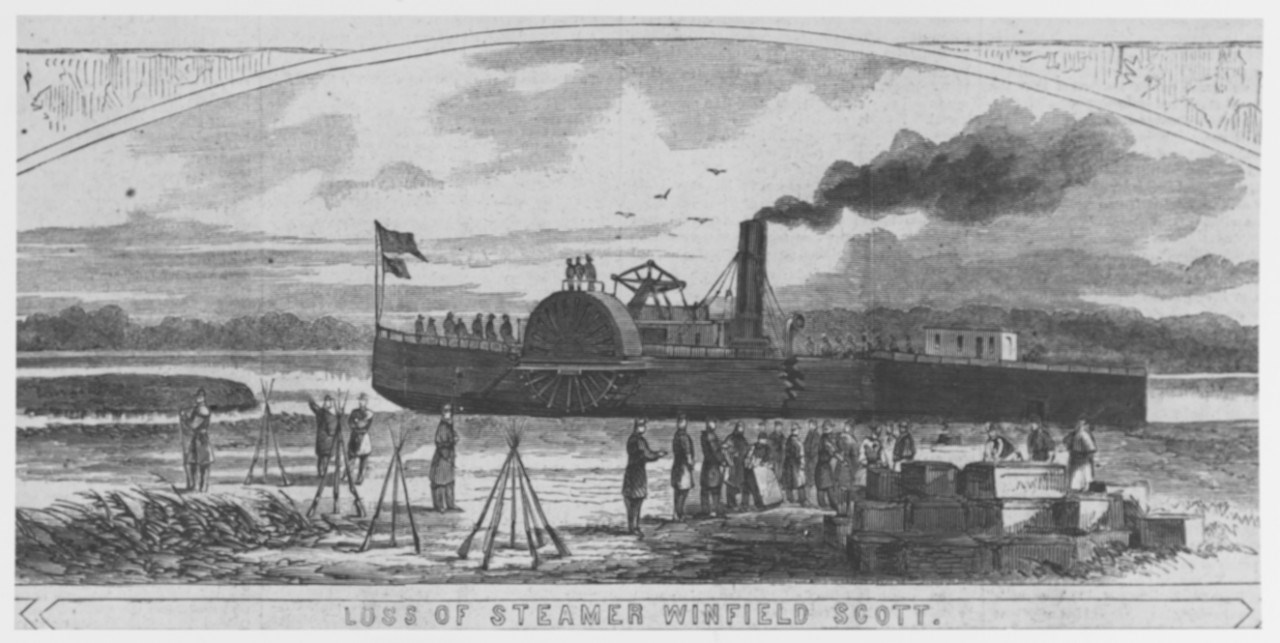

In late October 1861, a US naval fleet assembled for an expedition and left from Annapolis, via Norfolk, to begin the journey to South Carolina. At the time, it was the largest fleet ever assembled by the United States.1 While at sea, the fleet would be devastated by a large storm that lasted two days and three nights. Several ships went astray, and many even returned to port. Others, such as the steamer Winfield Scott, were substantially damaged and deemed unseaworthy.2 The fleet would be left substantially weakened ahead of their arrival at Port Royal. As a result, the initial plan for an amphibious operation was modified.3 While the United States encountered many difficulties ahead of the battle, the defending Confederate force was not free from its own share of challenges.

Naval History and Heritage Command

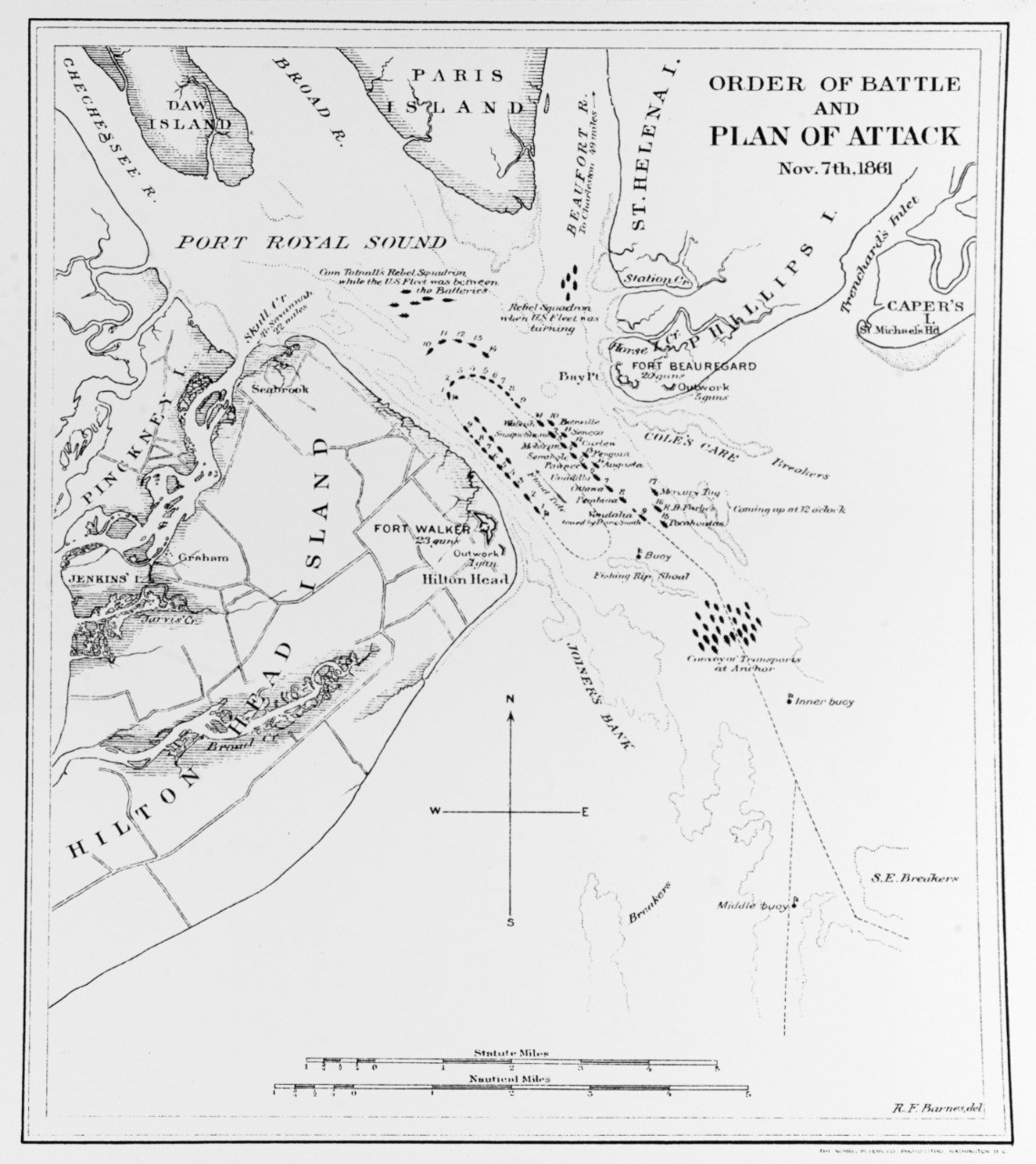

The entrance to the Port Royal Sound is flanked by two islands: Hilton Head Island (to the south) and St. Phillips Island (to the north). The Confederate defenses of the sound included one fortification on both islands: Fort Walker (Hilton Head Island) and Fort Beauregard (St. Phillips Island). To bolster the defenses of the forts, General Drayton (the commanding officer) had ordered several companies of troops from Savannah to Fort Walker as last-minute reinforcements.4 Additionally, Drayton had ordered a company of troops at Braddock’s Point (the western Portion of Hilton Head Island) to redeploy to Fort Beauregard. To cross the sound, they would need to go through Fort Walker. Due to a courier failure, Drayton’s message arrived at Braddock’s Point far later than expected. These troops successfully arrived at Fort Walker, but they were unable to cross the sound and resupply Fort Beauregard. The United States fleet forced the much smaller Confederate fleet to retreat into Skull’s Creek. Because the Confederate troops were unable to resupply Fort Beauregard, it was left susceptible to attack. After the battle, General Drayton would remark that the Confederate’s defeat at Port Royal could be largely attributed to these late deployments, the lack of preparation before the American attack, and the hasty construction of Fort Walker.5

The battle itself (sometimes called the “Big Gun Shoot”) came on November 7th, 1861. In a rout, the American fleet destroyed the Confederate fortifications on Hilton Head Island and St. Phillips Island. The battle, which lasted about six hours, concluded by 2:00 PM. This coincided with the surrender at Fort Walker. The troops at Fort Beauregard retreated before the arrival of American troops.6 In spite of the length of the battle, the American fleet was nearly unharmed. Why was this the case? During the battle, US Commodore DuPont employed a unique strategy. His fleet, while bombarding the forts, would sail through the sound in an elliptical pattern, minimizing the fleet’s exposure to return fire.7 Additionally, the Confederate defense was not well executed. Fort Walker was not designed to support all the guns that General Drayton had wanted. This meant that many cannons were packed too closely together, and that made defending the fort even more difficult.8 A large number of cannons were found to be defective and could not contribute to the defense. At the beginning of the battle, the two forts had 38 cannons in total. Within the first 30 minutes, they had already lost eight cannons. By the end of the battle, only 22 cannons remained to defend against DuPont’s armada.9

For perspective, the American fleet consisted of 18 warships, 55 supporting craft, and 13,000 troops; some estimates place the defending Confederate force at a mere 3,000 troops.10 The Confederate force was unprepared, out-manned, and out-gunned. After the battle, white planters in the region had fled from their properties. The Battle of Port Royal, the abandonment of property by white landowners, and the 10,000 formerly enslaved who now were free from bondage, opened the door for the forerunner to Reconstruction: The Port Royal Experiment.

During the experiment, freedpeople would get the opportunity to purchase land at tax auctions and attempt to establish their citizenship in the post-war South. To learn more about the tax auction, read the National Park Service’s article on the 1863 Beaufort District Tax Sales.

-

Eldredge, The Third, page 66.

-

United States Department of War, Official Record, page 7; 9-10; 19.

-

Eldredge, The Third, page 62; 64.

-

United States Department of War, Official Record, page 19.

-

Eldredge, The Third, page 65.