Last updated: May 20, 2024

Article

1863 Beaufort District Tax Sale

Huntington Digital Library

During the Civil War, tax auctions of abandoned properties on the Sea Islands around Beaufort were an important part of the Port Royal Experiment. Beginning in 1863, these tax auctions helped facilitate the redistribution of property and paved the way for generations of Black land ownership on the coast of South Carolina.

The redistribution of plantation land in the South Carolina Lowcountry was initially made possible from a series of legislation passed at the beginning of the Civil War, beginning with the Confiscation Act of 1861. This act stated that any persons enslaving peoples as property assisting or promoting insurrection were to be stripped of such “property” and placed into the care of the US Government. Although the act did not clarify the status of the Enslaved peoples they were placed into a status of “contraband.” The second piece of legislation was passed by Congress August 5, 1861, as the Revenue Act of 1861, which was an attempt to raise needed funds for the ongoing war. Essentially this act created an import tariff, property tax, and income tax on all US citizens, and led to the creation of the Internal Revenue Service in 1862. The last of these laws was passed on July 17, 1862, as the Confiscation Act of 1862. This act built onto the first Confiscation Act by furthering any punishments on those in or assisting those in rebellion against the United States, stating that “all the estate and property, moneys, stocks, and credits of such person shall be liable to seizure...” and be then property of the US Government. Unlike the first Confiscation act the second clarified the status of the formerly enslaved by stating, “and all slaves of such person found on [or] being within any place occupied by rebel forces and afterwards occupied by the forces of the United States, shall be deemed captives of war, and shall be forever free of their servitude, and not again held as slaves.” 1 This part of the act was of great importance, because it freed enslaved individuals a year before the Emancipation Proclamation. These three pieces of legislation served as the foundation of the 1863 Tax Auction and the even larger aspect of Reconstruction Era Black land ownership. Black land ownership was rare before the Civil War but existed. So, with the passage of this legislation, it paved the way for that opportunity around Beaufort.

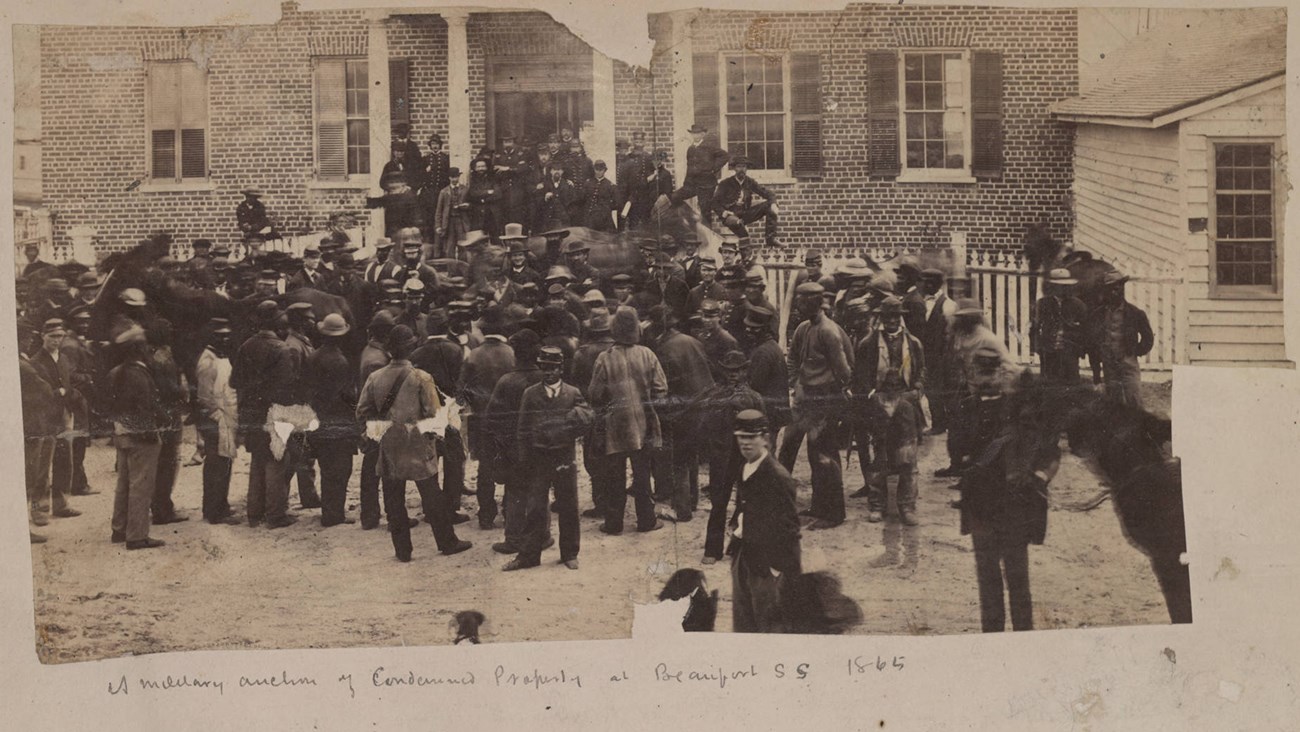

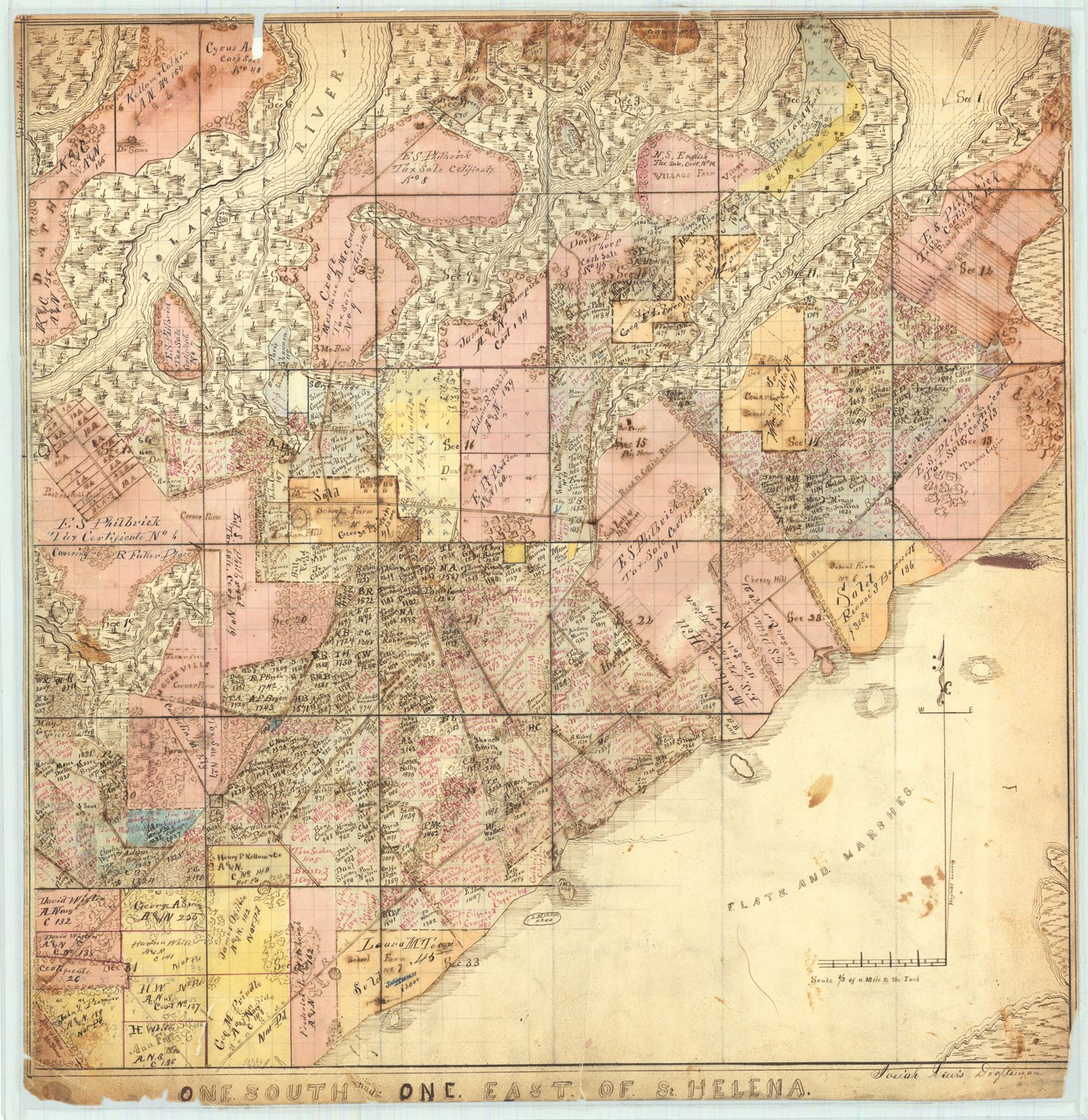

On November 7, 1861, a joint US military expedition landed on Hilton Head Island and forced the retreat of Confederate forces. With the arrival of the US Army to the area, the white planters of St. Helena Parish (what is now Beaufort and Jasper Counties) abandoned their land and fled to Confederate territories. Because of the Legislation of the Confiscation Acts and Revenue Act, these lands would become property of the US Government and the enslaved people of those lands “forever free of their servitude.” 2 The Secretary of Treasury Salmon P. Chase established a Direct Tax Commission and dispatched Tax Commissioners William Brisbane, Abram Smith, and William Wording to the Beaufort District to assess lands for auction. Rev. Dr. Brisbane was originally a slaveowner in Beaufort, but renounced the institution and moved north where he became an abolitionist. US occupation and the Port Royal Experiment gave him the opportunity to come home.The Tax Commissioners and General Rufus Saxton debated whether or not land should be set aside for Black heads of household. So, the first auction was postponed and 60,000 acres around Beaufort County were set aside. In March 1863, 16,000 acres of abandoned lands went on sale. Much of the land of this first sale was purchased by military personnel, including members of the 1st South Carolina Volunteers (later the 33rd USCT). Notably as part of this sale was Block #23 Lot B in Beaufort, where Robert Smalls purchased the house that he was born into slavery. Land sales of the Beaufort District would continue into 1890, with over 2,000 sales made to Black families. Even with these sales taking place a large amount of the Sea Islands was still owned by the US Government. The Internal Revenue Service also authorized one-year leases between individuals and Tax Commissioners, called indentures.

Like the Beaufort Tax Sales, the opportunity for Black landownership grew throughout the South at the close of the war, with Gen. William T. Sherman’s Special Field Order No. 15. Sherman’s order called for the 400,000 acres of confiscated coastal lands from Charleston, SC to Jacksonville, Fl for the settlement of the formerly enslaved. Unlike the land sold in the tax sales, most of this land would revert to its original prewar ownership due to President Johnson’s Amnesty Act. Initially Gen. Saxton largely ignored the President’s order disproving all requests for the return of confiscated land. This would prove costly to Gen. Saxton as Johnson relieved Saxton of his command for his actions.

National Archives

Newly freed people were either wary of the government or lacked reliable legal counsel. This led to deeds not being recorded by government officials and lost over time, leaving heirs of the land unable to prove ownership. Freedpeople also rarely created a will to pass their lands down properly, and their lands were considered heirs’ property, which made it easier for forced sale and eviction. Stripped of their legally purchased lands, Black farmers were forced into sharecropping agreements, which were barely concealed (and legal) attempts at reinstituting the labor systems which existed pre-war. Disputes over legal land ownership with heirs’ property and missing land deed documents, contributed to successful legal challenges by former landowners reclaiming their property.

Those Black Americans who successfully retained land in court cases were subject to predatory loans, racist attacks, and outside legal issues that would see their lands chipped away. Although land sales like the 1863 Beaufort Tax Sale saw an initial promise of Black land ownership throughout the American South, by 1867, all but 75,000 of the original 400,000 acres of confiscated coastal land was reverted to the ownership of the original landowners. The importance of Black families owning land from the war time tax sales in the Beaufort District is of great importance to the overall picture of post-war Black landownership. Being able to hold onto their lands moving into the 20th century gave the Black families of Beaufort more economic stability than those Black families in the South that would see their land settled back into the hands of the former planter class.

- U.S., Statutes at Large, Treaties, and Proclamations of the United States of America, vol. 12 (Boston, 1863), pp. 589-92.

- Ibid