Last updated: October 19, 2020

Article

Bat Projects in Parks: North Coast Cascades Network

Millions of bats live in national parks. Eleven bat species occur in North Coast Cascades Network Parks. Bats eat beetles, moths, and mosquitos. They rest in snags, talus, cliffs and buildings during the day and use excellent eyesight and echolocation to navigate the night skies. They fascinate visitors. Some migrate, and some hibernate. Each species is unique, except that they're all facing threats of some kind in their environments.

How scientists study bats

NPS Photo

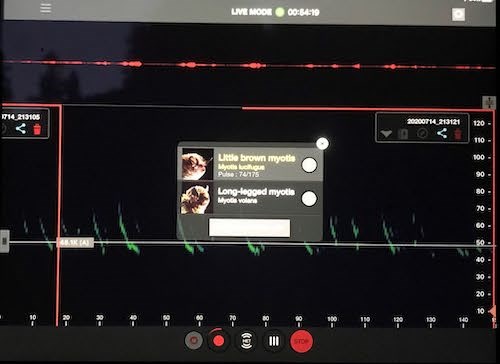

Acoustic Monitoring

When bats such as the little brown bat fly at night, they communicate using unique ultrasonic calls. The little brown bat’s unique call is around 40kHz. Other animals such as rodents, cats, whales, dolphins and porpoises can also hear these high frequency soundsbut humans can typically only hear sounds up to 20kHz. Bats have different patterns to their calls based on whether they are navigating, approaching a resting place, searching for food, feeding, or socializing. Scientists use specialized microphones to record these higher frequency sounds, and software to then identify a species’ unique call and behavior.

Acoustic detectors can be placed at stationary points to record the relative activity level of bats in a specific location or scientists can drive along a designated route, called a mobile transect, to estimate the number of individual bats that are active during the survey. Acoustic monitoring in the winter can help identify areas with bat activity that is expected, and activity that is unusual. Silver-haired bats are occasionally detected in Washington National Parks in the winter but western long-eared bats are not usually detected until the spring. If bats that should be hibernating are detected in winter months, scientists may respond by increasing white-nose syndrome surveillance in the area and investigating other causes for unusual activity, such as storm activity or a warm weather event.

NPS Photo

Population Counts

Like all animals, bats need rest. Bats are primarily active a night and rest in day roosts. Bats emerge from their day roosts shortly after sunset and may rest at a night roost after foraging. They may leave their night roost forage for a second dinner before returning to their day roost. Female bats congregate in maternity colonies, where the pups stay safe and warm while their mothers are out hunting.

In the spring and summer, as bats fly out of their day roost to hunt for insects, scientists are standing by to count them as they go out to feed. Emergence counts allow scientists estimate the size of the bat colony, the number of young in maternal colonies, and changes in phenology, such as the time of year bats arrive to the colony, when pups learn to fly, and the time of year they depart to autumn and winter habitats.

White-nose Syndrome (WNS)

WNS is a fungal disease that affects bats during hibernation. A fungus called Pseudogymnoascus destructans(Pd) causes WNS. It is often displayed as a powdery white substance around infected bats’ muzzles and wings. It's killed millions of bats in the US, up to 99% of some populations. Scientists first discovered WNS in New York in the winter of 2006-2007. WNS is spread from bat to bat when they touch and Pd can survive on the surfaces of a hibernacula in the absence of bats. This can lead to reinfection the following season. Scientists also think that humans have the potential to carry the fungus from infected colonies to non-infected colonies, increasing the rate of spread. Park scientists are monitoring bats and conducting WNS surveillance to determine local impacts.

WNS only affects bats and is not dangerous to humans or pets. If you find a sick or dead bat do not touch the bat but be sure to tell a Park Ranger so it can be tested for diseases. These bats will be removed to protect both humans and other bats.

What can you do to help?

Bats elicit a variety of responses in people –awe, wonder, curiosity, fear. Understanding the important role bats play in our environment and communicating that importance to others can help reduce the negative feelings some people feel toward bats.

- Avoid accidental transport of animals and plants. When you’re visiting parks or traveling away from home, check tent flies, canopies, and awnings before leaving to make sure you’re not accidently taking wildlife with you –bats, insects or other animals.

- Before leaving your camp site, clean seeds off of your vehicle, tent, clothing, shoes and gear to avoid transporting them to a new area. Wash your vehicles and gear frequently, removing all mud.

- If you have entered a cave or other bat habitat, follow decontamination instructions to ensure you are not accidently spreading the fungus that causes white-nose syndrome.

- At home you can improve the habitat around your home by leaving standing snags where safe to do so, putting up a bat house, and planting wildlife friendly landscapes.

References

Tags

- ebey's landing national historical reserve

- fort vancouver national historic site

- lewis and clark national historical park

- mount rainier national park

- north cascades national park

- olympic national park

- san juan island national historical park

- mount rainier science

- bats

- white-nosed syndrome

- wns

- wildlife

- mammals