Last updated: March 21, 2024

Article

Bat Monitoring at Voyageurs National Park, 2015–2019

USGS/P. Cryan

Bats nationwide are struggling to survive against threats posed by climate change, habitat loss, wind turbines, and a devastating fungal disease called white-nose syndrome (WNS).

Four of the bat species found at Voyageurs are only here in the summer; they spend their winters in the southwestern U.S., Mexico, and even Central America (Table 1). The others, rather than migrating, hibernate here over the winter, roosting in caves or buildings. Three of these hibernating species—the little brown, northern long-eared, and tricolored bats—are highly susceptible to WNS. The big brown bat is also a hibernating species but has exhibited resistance to the disease.

Table 1. Bat species documented at Voyageurs National Park before the start of a formal monitoring program in 2015 and after five years of acoustic monitoring (2019). Asterisk (*) indicates winter hibernating species.

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Pre-2015 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Big Brown Bat * | Eptesicus fuscus | N | Y |

| Eastern Red Bat | Lasiurus borealis | N | Y |

| Hoary Bat | Lasiurus cinereus | N | Y |

| Little Brown Bat * | Myotis lucifugus | Y | Y |

| Northern Long-eared Bat * | Myotis septentrionalis | Y | Y |

| Silver-haired Bat | Lasionycteris noctivagans | Y | Y |

| Tricolored Bat * | Perimyotis subflavus | N | Y |

Before our monitoring program began in 2015, only three bat species were known to be flying over Voyageurs: little brown bat, northern long-eared bat, and silver-haired bat. Little brown bats were the only species found during a survey of five park buildings in 2010, with several locations identified as likely maternity colonies. Bat surveys conducted by the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (MNDNR) in the 1980s documented big brown, eastern red, and hoary bats in St. Louis and Koochiching Counties, adjacent to the park, but the exact locations were not specified. The Minnesota Biodiversity Atlas lists hoary bat specimens collected in 1966 from both counties, and big brown bat echolocation calls were recorded at the Soudan Underground Mine near Tower, Minnesota, approximately 50 miles away from the park.

Mist-netting surveys conducted in 2015–2017 by the MNDNR and the University of Minnesota-Duluth’s Natural Resources Research Institute captured six species in St. Louis County: big brown bat, eastern red bat, hoary bat, silver-haired bat, little brown bat, and northern long-eared bat. Acoustic surveys yielded confirmed recordings of the same six species in both St. Louis and Koochiching Counties. They even captured possible recordings of tricolored and evening bats.

The evening bat’s range ends near Minnesota’s southern border, so it is unlikely to be here. But the edge of the tricolored bat’s range is a little closer. This species has not been recorded in the park, but it has been found hibernating at the Soudan Mine, and there are records from Hovland, Minnesota, and Palisade Head near Silver Bay, Minnesota.

Breaking the Ultrasonic Barrier

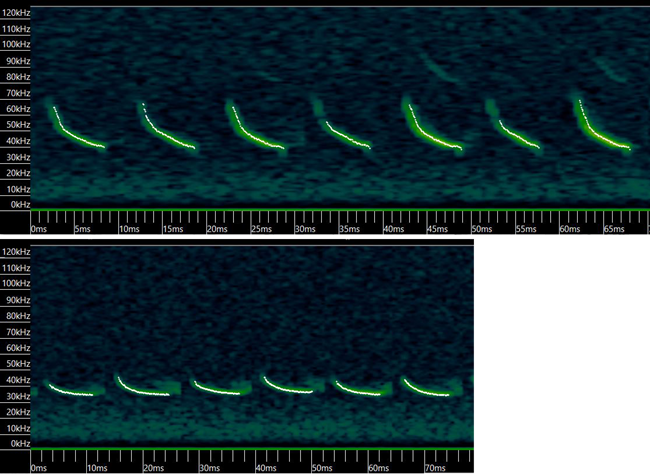

Bats give different calls while in flight to help them navigate and to locate things like food. Like bird songs, we can identify bat species by their calls, but the calls are ultrasonic—beyond the range of human hearing—so special microphones and software are used to record and identify them. But, also like birds, some bat species have similar calls, and there can be variation in the calls of any one species. As a result, the software we use to analyze and identify the recordings is not 100% accurate. In these cases, a proportion of call files are reviewed “manually” using a spectrogram to verify the identifications.

We Have Seven!

The three bat species previously documented at the park were reconfirmed: silver-haired, little brown, and northern long-eared bats. Four additional species were documented through both automated classification and manual vetting: big brown, eastern red, hoary, and tricolored bats. Apart from the tricolored bat, the presence of these species was expected since the park lies well within their known ranges. We obtained one manually verified tricolored bat recording, suggesting that this species is at least occasionally present in the park.

The little brown bat was the most commonly recorded species in 2015–2017, then dropped to second behind the hoary bat in the next two years. The silver-haired bat accounted for only 5%–7% of call files in the first three years, but then became more prominent. Hoary and silver-haired bats were the only two species recorded at every sample site every year.

Activity levels for big brown, hoary, and silver-haired bats appear to be stable or slightly increasing, but activity levels for eastern red, little brown, northern long-eared, and tricolored bats all show declining trends.

NPS photos unless credited otherwise

The Future of Bat Monitoring

We are working with the NABat Midwest Bat Hub (https://midwestbathub.nres.illinois.edu/) to create statistical models of bat occupancy, particularly those most affected by WNS. Occupancy measures the probability that a species is using an area, while taking into account the fact that we cannot always perfectly detect the species.

When this project began, the Great Lakes region was at the leading edge of the WNS spread. This monitoring program helped parks to document baseline data on their bat populations and to assess changes over time. However, the Great Lakes Network handed all aspects of bat monitoring over to the parks in 2022, so any further monitoring at Voyageurs will be conducted by park biologists.