Last updated: March 14, 2024

Article

Bat Monitoring at Grand Portage, 2016–2019

Bats nationwide are struggling to survive against threats posed by climate change, habitat loss, wind turbines, and a devastating fungal disease called white-nose syndrome (WNS).

Prior to the beginning of this monitoring program in 2016, only the little brown bat and the hoary bat were detected during general wildlife surveys at Grand Portage in 1992–1994. Four additional species were recorded during a survey in 2003 that specifically targeted bats by collecting acoustic recordings, capturing bats by mist-netting, and conducting roost surveys.

Among the bats found at Grand Portage (Table 1), the eastern red, hoary, and silver-haired bats are only here in the summer, then migrate to the southwestern U.S., Mexico, and even Central America for the winter. While here, they roost in trees, clinging to branches and bark. The big brown, little brown, northern long-eared, and tricolored bats do not migrate. They hibernate here over the winter, roosting in caves and buildings. Except for big brown bats, which show greater resistance to the disease, the hibernating bats are highly susceptible to WNS. In addition, the northern long-eared bat is a federally endangered species under the Endangered Species Act.

Table 1. Bat species documented at Grand Portage before the start of this monitoring program in 2016 and after four years of acoustic monitoring (2019). Asterisk (*) indicates winter hibernating species.

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Pre-2016 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Big Brown Bat * | Eptesicus fuscus | Yes | Yes |

| Eastern Red Bat | Lasiurus borealis | Yes | Yes |

| Hoary Bat | Lasiurus cinereus | Yes | Yes |

| Little Brown Bat * | Myotis lucifugus | Yes | Yes |

| Northern Long-eared Bat * | Myotis septentrionalis | Yes | Yes |

| Silver-haired Bat | Lasionycteris noctivagans | Yes | Yes |

| Tricolored Bat * | Perimyotis subflavus | No | Yes |

Breaking the Ultrasonic Barrier

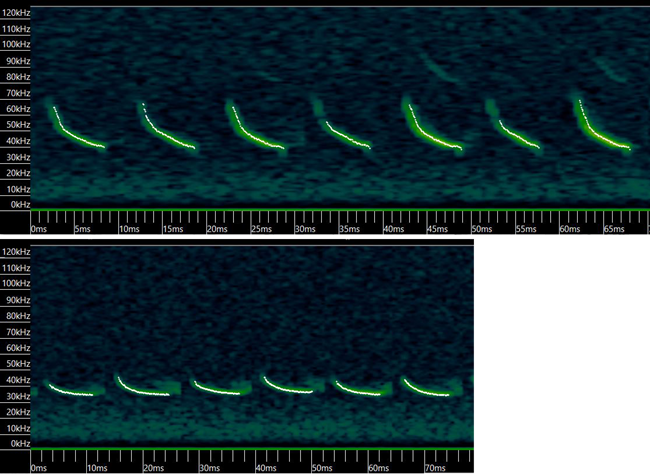

Beginning in 2016, we placed ultrasonic audio recorders along the portage trail and two each on the grounds near Lake Superior and at Fort Charlotte to identify what bat species are present. Bats give different calls while in flight to help them navigate and to locate things like food. Like bird songs, we can identify bat species by their calls, but the calls are ultrasonic—beyond the range of human hearing—so special microphones and software are used to record and identify them. However, also like birds, some bat species have similar calls, and there can be variation in the calls of any one species. As a result, the software we use to analyze and identify the recordings is not 100% accurate. In these cases, a proportion of call files are reviewed “manually” using a spectrogram to verify the results produced by the software.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service photos

All Accounted For, Plus One!

Our monitoring reconfirmed the presence of the six bat species previously documented at Grand Portage: big brown, eastern red, hoary, little brown, northern long-eared, and silver-haired bats. A seventh species, the tricolored bat, was newly documented. Tricolored bats have not been physically captured in the park, but our acoustic data suggest this species is present.

The little brown bat and northern long-eared bat were the most commonly recorded species in 2016, comprising 60% and 16% of the total files, respectively. However, the frequency of recordings for both species dropped to 17% or fewer in each of the following three years. Northern long-eared bats were recorded at every survey site in 2016, and the silver-haired bat was present at every site every year. Conversely, the eastern red bat was heard at fewer sites each year, ranging from 94% to 39% of sites over the four years.

Overall, the activity levels for big brown, hoary, and silver-haired bats appear to be stable. There are declining activity trends for little brown, northern long-eared, eastern red, and tricolored bats, all of which (except the eastern red bat) are hibernating species susceptible to white-nose syndrome.

The Future of Bat Monitoring

When this project began, the Great Lakes region was at the leading edge of the WNS spread. This monitoring program helped parks to document baseline data on their bat populations and to assess changes over time.

We are working with the NABat Midwest Bat Hub (https://midwestbathub.nres.illinois.edu/) to create statistical models of bat occupancy, particularly those most affected by WNS. Occupancy measures the probability that a species is using an area, while taking into account the fact that we cannot always perfectly detect the species.

The Great Lakes Network handed over the equipment and responsibility for coordinating bat monitoring to Grand Portage staff in 2023.

NPS photos unless credited otherwise