Last updated: September 26, 2022

Article

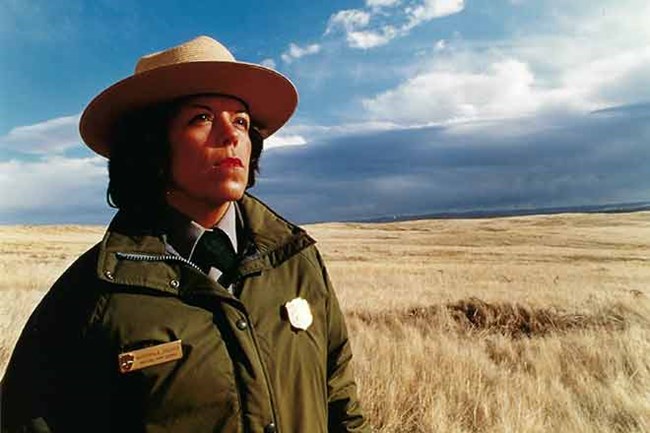

Barbara Ann Sutteer (Booher)

Barbara Ann Sutteer was born and raised on the Uintah and Ouray Indian Reservation in Utah. Her mother was Northern Ute, and her father was Cherokee. They both worked for the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA).

In 1954 Public Law 671 was passed, ending a dispute within the Northern Ute Tribe. They accepted a division of assets and the termination of federal recognition for people with one-half or less Ute blood; federal trusteeship over their property and affairs ended by August 27, 1961. Sutteer, who had begun college at the University of Utah around 1960, had to drop out when she lost her tribal benefits, including federal aid for education.

In 1969, about the same time that she began her federal career, she married Hal Booher. Three years later they moved to Anchorage, Alaska, for his job as Bureau of Land Management (BLM) planner. She finished her studies at Alaska Pacific University, earning a degree in commercial and graphic art. In Alaska she worked as a realty officer for the Federal Aviation Administration and BIA. She also worked with the National Park Service (NPS) on the Alaska Task Force, which was responsible for assessing new park areas in the state. In 1986 she became an allotment coordinator for BIA, liaising with BLM. Her main duties involved helping Alaskan Natives acquire their allotment and townsite lots. She served in the BIA for 17 years.

In 1988 the BIA selected her for an executive management training program. In March 1989 she completed a two-week detail with the NPS at the Rocky Mountain Regional Office. Regional Director Lorraine Mintzmyer was impressed by her work and offered her the job of superintendent at Custer Battlefield National Monument. Booher accepted and on July 16, 1989, became the second Native American woman superintendent, fifteen years after Ellen Lang was the first Native Alaskan superintendent.

Some saw Booher’s appointment as controversial because she had never worked for the NPS before becoming superintendent. In a 1990 newspaper interview, Mintzmyer noted, “I recognized that her Native American heritage might be a plus for her in an area where many Native Americans live and work, but I hired her because of the skills she demonstrated, not because of her heritage.”

As superintendent, Booher brought change to the monument. In her first year, she doubled the number of Native American employees, argued with critics to have the book Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee sold in the gift shop, and made plans to change the direction of the park’s exhibits, brochures, and other interpretive materials. Booher noted, “All I’d ever heard about it in school was from the Custer point of view, and when I came here on my own as a tourist in 1973, I thought, ‘Well, that’s all calvary. This is the only place where all the monuments are to the losers.’"

Her determination to tell the story of the Native Americans at the Battle of Little Bighorn and to convey the reasons for and significance of the battle rather than celebrating Custer earned her criticism from some local historians and Jim Court, the park’s former superintendent. In an August 1990 newspaper article, Janine Pease Windy-Boy, president of Little Big Horn College, noted, “It’s been a coming of age for a monument that has been in the dark ages. Barbara’s a breath of fresh air. Superintendents prior to her were consistently interested in military history from the Custer point of view. There’s nothing more symbolic than an Indian and a woman to upset these so-called historians who are mostly white and male.”

Most significantly Booher assisted with the 1991 legislation that changed the name of Custer Battlefield to Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument. The year after the name change went into effect, visitation rose 21 percent. In 1991 Congress also authorized the establishment of a Native American memorial at the park. Sutteer recalled her reaction on the day she found out that the memorial had been approved, explaining how it “was the victory call. It was our song. We still sing that song today. It’s still a victory.” The memorial was completed in 2014.

In an article published in the Argus-Leader (Sioux Falls, SD) she reflected on her accomplishments at the monument. “I was told it would be a tough assignment, and now I know what that means. This is not a job, it’s a way of life.”

When her marriage ended in the 1990s, she reverted to her maiden name. In 1993 Sutteer became the Indian Affairs coordinator at the NPS Rocky Mountain Regional Office (RMRO). Her primary responsibility was working with Native American Tribes whose use and occupancy of lands predate the NPS. She consulted with Tribes about Wounded Knee Massacre Site, Devil’s Tower National Monument, Pipestone National Monument, and Washita Battlefield National Monument. She wrote a tribal consultation plan and assisted with gathering oral histories from Cheyenne and Arapaho family descendants when Congress mandated that the NPS study the Sand Creek Massacre Site in 1998. For this project the NPS worked alongside descendants to conduct archeological field surveys and collect and identify artifacts from the site, ultimately leading to the authorization of Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site in 2001. Sutteer also played a role in implementing the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.

Sutteer retired from the NPS in 2001, after 32 years of federal service. Her final project with the NPS involved the establishment of the NPS Office of American Indian Trust Responsibility.

In retirement she became a board member for the Mesa Verde Foundation and, in 2005, joined the board of the First People’s Center for Education. She also serves as a board secretary for the National American Indian, Alaskan, and Hawaiian Education Development Center. She continued to work with the NPS in consultations with Native American Tribes. In an interview in The Oskaloosa Herald she reflected on her role as a liaison for Native American communities. “They always talk about Indians, but they’re just now realizing that they have to talk with Indians. That’s where I come in as a facilitator to help federal or other people consult with Indian tribes.”

Sources:

Ancestry.com. U.S., Newspapers.com Obituary Index, 1800s-current [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2019.

Barbara A. Sutteer. (n.d.). University of Colorado. Retrieved February 28, 2022, from https://www.colorado.edu/center/west/barbara-sutteer

Bartimus, T. (1990, August 5). “Indian park chief draws fire.” The Berkshire Eagle. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

Bartimus, T. (1990, August 12). “Little Bighorn supervisor sparks new fight.” Argus-Leader. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

Bartimus, T. (1990, August 5). “Park Official Makes Stand at Battlefield Where Custer Fell.” The Salt Lake Tribune. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

Goodell, A. (2011, September 14). “Penn speaker provides Native-American perspective.” The Oskaloosa Herald. Retrieved February 28, 2022, from https://www.oskaloosa.com/news/local_news/penn-speaker-provides-native-american-perspective/article_91ac049f-b45b-5b68-b859-bd77696d64c8.html

“Indian memorial at Little Bighorn Battlefield is finally complete.” (2014, June 26). Retrieved February 28, 2022, from https://www.indianz.com/News/2014/06/26/indian-memorial-at-little-bigh.asp

“Local Indian woman assigned post at national monument.” (1980, June 28). The Uintah Basin Standard, p. 15.

“’Mixed Blood’ Members of Utah Indian Tribe Moved to Set up Own Organization Under Termination Law.” (1956, April 17). Accessed March 7, 2022 at https://www.bia.gov/as-ia/opa/online-press-release/mixed-blood-members-utah-indian-tribe-moved-set-own-organization.

“Monument Valley’s wild beauty elicits Japanese admiration.” (1996, October 15). Elko Daily Free Press.

National Park Service. (1989, September). “News.” Courier, volume 34, Number 9, p. 28.

National Park Service. (1992, March). “Park Briefs.” Courier, volume 37, Number 3, pp 14.

National Park Service. (1993, February). “New Faces, New Places.” Courier, volume 38, Number 2, p. 4.

National Park Service. (1993, Summer). “New Faces, New Places.’” Courier, volume 38, Number 5, p. 6.

National Park Service. (2001, Summer). “Class of 2001.” Arrowhead, volume 8, number 3, p. 6.

“No Surrender.” (2004, May 2). Retrieved February 28, 2022, from https://www.outsideonline.com/outdoor-adventure/no-surrender/

Olp, S. (2014, June 29). “Ceremony marks completion of Indian Memorial on anniversary of battle.” The Montana Standard.

Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site. (2019, March 18). “Barbara Sutteer.” [Facebook Post]. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/SandCreekMassacreNHS/posts/2270404516349943

Explore More!

To learn more about the history of women and the NPS uniform, visit Dressing the Part: A Portfolio of Women's History in the NPS.

This research was made possible in part by a grant from the National Park Foundation.