Last updated: April 30, 2024

Article

Aquatic Community Monitoring at Hoover Creek from 2008 to 2017

NPS

Why Monitor Aquatic Animals?

Fish and aquatic invertebrates, such as insect larvae, worms, crayfish, snails, and other animals without backbones, can tell us a lot about water quality in the streams they live in! These relatively long-lived and diverse animals often react strongly and predictably to changing water conditions. Monitoring fish and aquatic invertebrates can reveal cumulative impacts to aquatic systems, whereas traditional water quality measurements are just a snapshot in time.

Not all fish or invertebrates are equally sensitive to changes in their environments though. Some species are considered “tolerant,” while others are “intolerant.” Tolerant species can survive in habitats with a larger range of conditions, and intolerant taxa will experience population decline or migrate elsewhere in altered conditions. Following trends in aquatic community composition and habitat conditions is a robust way to assess stream integrity and health.

Monitoring Hoover Creek

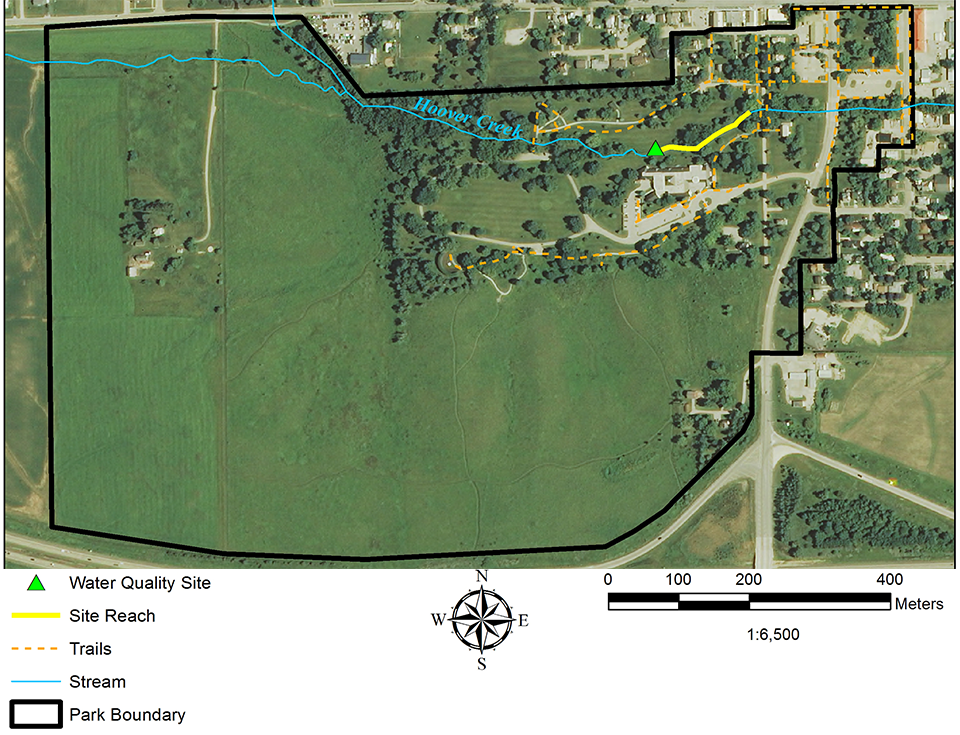

Herbert Hoover National Historic Site (NHS) in eastern Iowa contains a 1.3-kilometer segment of an unnamed tributary—known as Hoover Creek—of the West Branch of Wapsinonoc Creek. Dominant land uses in the watershed are agricultural, rural residential, and urban uses. Several water quality standards have been violated leading to the listing of the creek as an impaired stream under Section 303(d) of the Clean Water Act. Land use changes can degrade water quality and stream habitat and are a major factor in shifts and declines in aquatic communities throughout the Midwest.

The Heartland Inventory and Monitoring Network has monitored a downstream section of Hoover Creek since 2008. The goal of this long-term monitoring effort is to determine the status and trends in fish and aquatic invertebrate populations and relate that information to water quality and habitat conditions within Hoover Creek.

NPS

NPS

How We Monitor Aquatic Communities

We use a special net called a Surber Stream Bottom Sampler to collect invertebrates in Hoover Creek. To sample fish, we use a pulsed direct current backpack electrofishing unit and dip nets. Before releasing the fish back in the stream, we identify them to species, measure and weigh them, and examine them for disease. We also collect information on stream habitat and stream shape, depth, and flow.

To collect traditional water quality measurements, such as temperature, dissolved oxygen, pH, specific conductance, and turbidity, a calibrated water quality datalogger is placed upstream of our aquatic invertebrate sampling area. This allows us to compare water quality results with the composition of the aquatic animal community.

What We Found

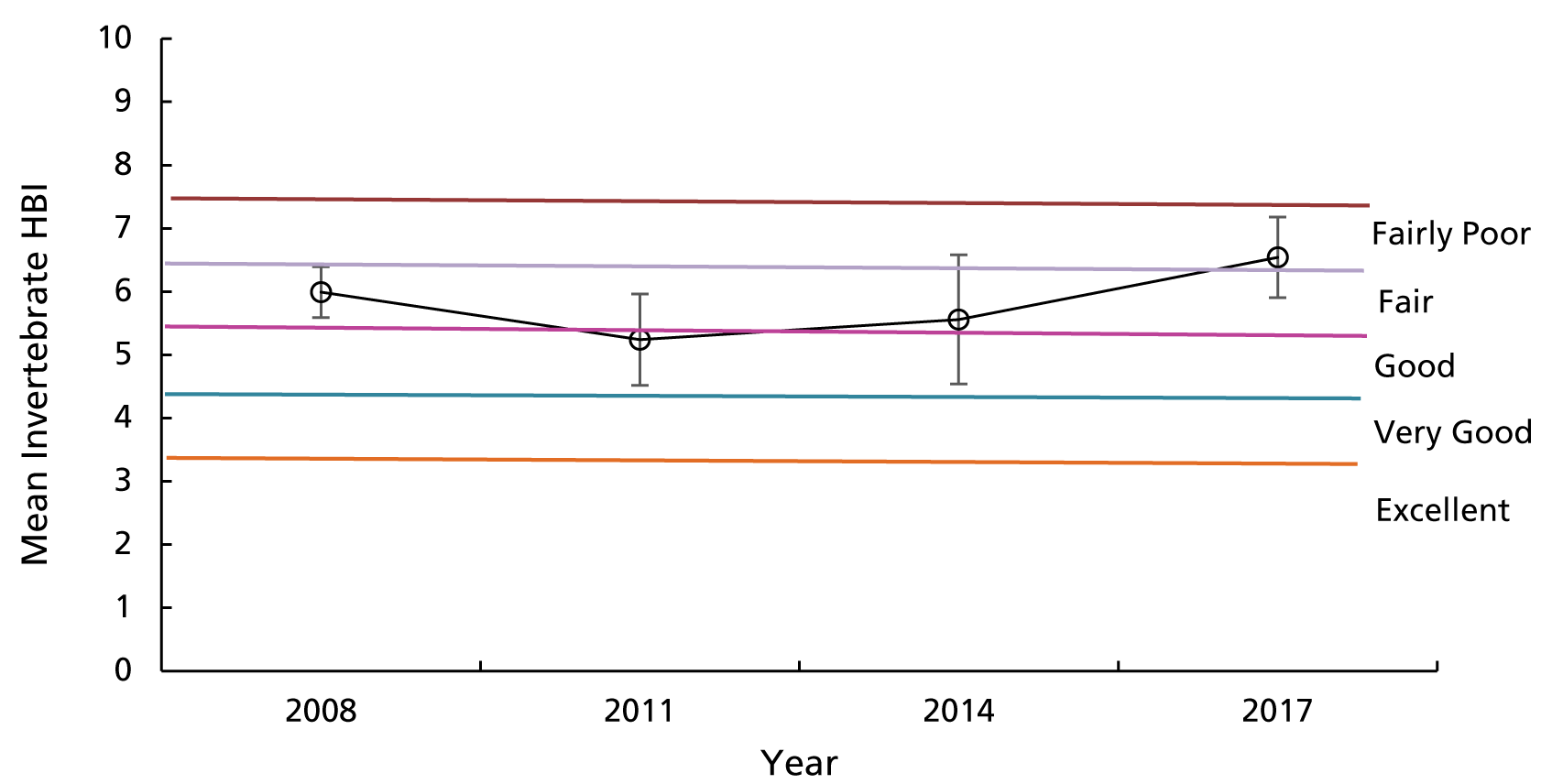

A total of 45 aquatic invertebrate taxa have been collected during our monitoring of Hoover Creek. Three of these taxa are sensitive to poor water quality conditions. In 2011, a sensitive caddisfly in the Ceratopsyche genus was the most abundant aquatic invertebrate. However, across the four years of monitoring, we found that the aquatic community is dominated by taxa that are tolerant of poor water quality and habitat conditions: true flies in the Chironomidae family, Oligochaete worms, and mayflies in the Baetidae family. Abundance of these three taxa appear to decline over time, but the Oligochaete worms and Baetid flies actually make up more of the aquatic invertebrate community in later years. The aquatic invertebrate community fluctuated from good condition in 2011 to fairly poor condition in 2017.

NPS

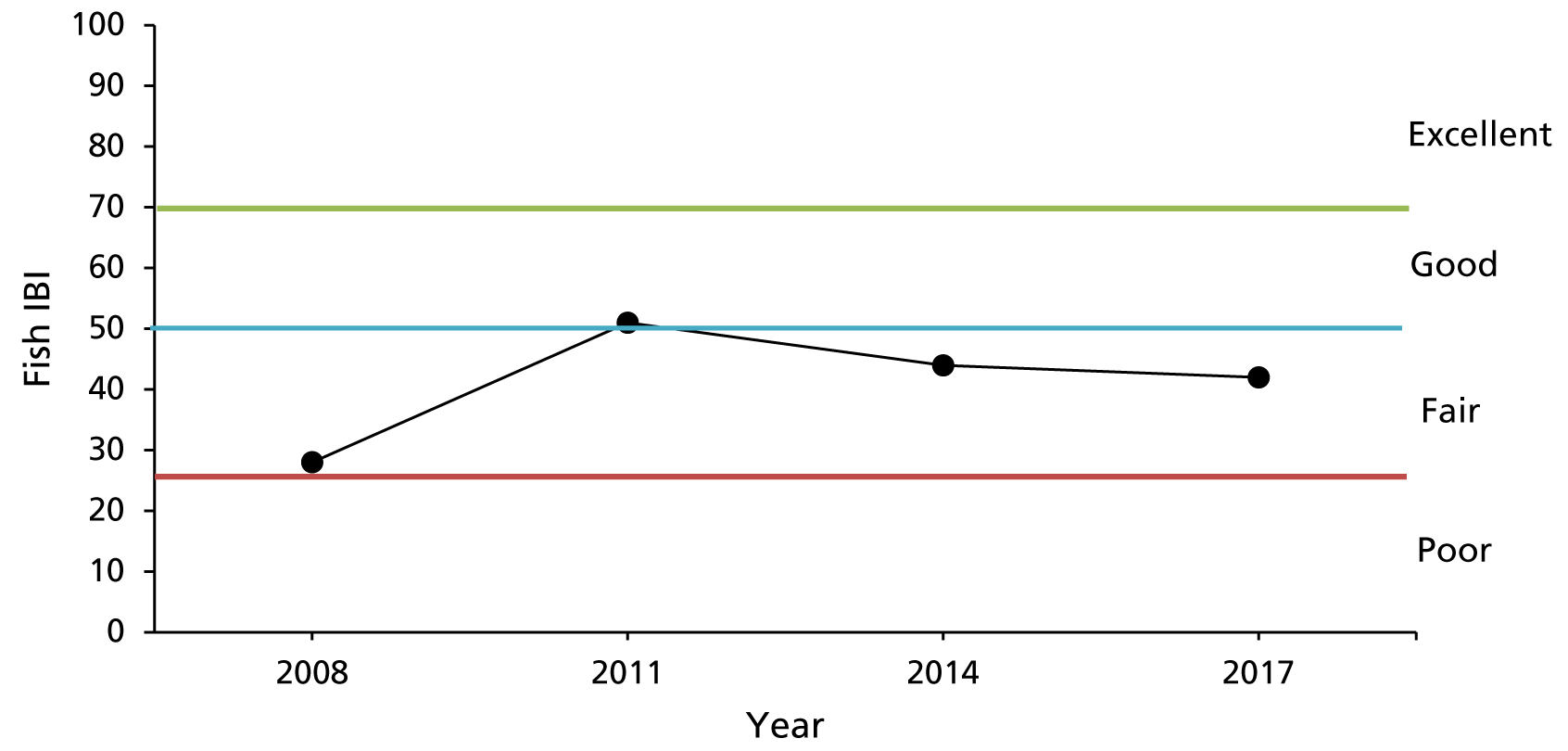

Ten fish species were collected in Hoover Creek in the four years of sampling, and seven of these species were found in all four years. All fish species collected were either moderately tolerant or tolerant to poor habitat and water quality conditions. Johnny darter (Etheostoma nigrum), creek chub (Semotilus atromaculatus), and blacknose dace (Rhinichthys atratulus) dominated the fish community, which ranged from fair condition in 2008 to good condition in 2011. While the fish community in 2017 was similar to other years, there were three times more deformities, eroded fins, lesions, and tumors than noted in other years.

NPS

NPS

Animal Highlight: Netspinner Caddisflies

Caddisflies are important components of aquatic ecosystems. Both the larvae that live in the water and the adult caddisflies are a vital food source for fish. There are many different kinds of caddisflies, including netspinners caddisflies. Some netspinners are in the Ceratopsyche genus, and these caddisflies were the most abundant aquatic invertebrate in Hoover Creek in 2011.

Netspinner caddisflies eat algae and other organisms they filter from the water with nets they create out of silk. The silk is very strong and can stay in place even in heavy water flow. The nets can also create habitat for other aquatic animals by reducing water flow and even holding large gravel in place. The caddisfly's sensitivity to changes in the aquatic environment and their role in filtering water, breaking down plant and animal material, and creating habitat make them good indicators of aquatic system health. Caddisflies are one of the animals we monitor to understand the condition of Hoover Creek and how it might be changing over time.

For More Information

Visit the Heartland Inventory and Monitoring Network website.

Tags

- herbert hoover national historic site

- htln

- heartland network

- heho

- hoover creek

- aquatic

- aquatic invertebrates

- aquatic invertebrate monitoring

- aquatic animals

- invertebrate

- monitoring

- fish

- fishes

- fish monitoring

- aquatic ecology

- water quality

- water quality monitoring

- stream monitoring

- scientific research

- science

- research

- midwest

- iowa

- heartland inventory and monitoring network