Part of a series of articles titled Commemorating ANILCA at 40.

Article

ANILCA, Navigability, and Sturgeon

Gavin DeMali has worked as a realty specialist focused on Navigability for the NPS Alaska Regional Office since July of 2021. He first came to Alaska in July of 2020 as a Natural Resource Management Assistant intern through the Scientists in the Park (SIP) program, where he worked to help catalogue and digitize NPS’s Navigability archives and worked on conducting Navigability-related research. He earned his Bachelor of Science in Geology with minors in Anthropology and Arabic from the University of Akron in Spring of 2020.

NPS/D. LILES

The passage of ANILCA saw the expansion of protected status to massive swaths of Alaska, encompassing millions of acres of newly designated national parks, preserves, and other conservation units. The legislation sought to extend protection to conserve these expansive landscapes and the waters that run through them, some of which being so central to the conception of these newly designated units that they became their namesake. But while ANILCA emphasized the conservation of these areas, it also included compromises to protect the interests of Alaskans in ways atypical in comparison to national parks in other states.

These compromises touch on a number of subjects that have wide ranging implications, and the conservation and jurisdiction of the water bodies within ANILCA conservation system units (CSUs) are no exception. These implications were made apparent to the National Park Service in Alaska when rangers in Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve stopped a man on a hovercraft on the Nation River in 2007. The rangers warned the man that his hovercraft was not allowed in the preserve based on NPS regulations and he subsequently left. The issue was not dropped there, however, as this man, John Sturgeon, went on to file a lawsuit against the National Park Service arguing that a specific portion of ANILCA prevents the NPS from enforcing their regulations on navigable waters.

Sturgeon argued that Section 103(c) of ANILCA prevents NPS from enforcing their regulations on the Nation River and other waters whose submerged lands are owned by the State (Sturgeon v. Frost, 577 U.S. ___ (2016)). Section 103(c) prevents lands within conservation system units that are owned by the State, Alaska Native Corporations, or that are privately owned from being subject to regulations applicable solely to public lands. This provision was a compromise to prevent the lives of those who already lived within the newly designated units from being disrupted by their creation (16 U.S.C. § 3103(c)). The case proceeded through the District Court and 9th Circuit Court of Appeals and then came before the Supreme Court who decided that 103(c) draws a distinction between public and non-public lands and remanded the case to the circuit court to decide if the Nation River was public land (Sturgeon v. Frost, 577 U.S. ___ (2016)). When the case made it back to the Supreme Court (Sturgeon v. Frost, 587 U.S. ___ (2019) “Sturgeon II”), they issued a unanimous decision that the Nation River was not public land by virtue of its state ownership, and therefore it (and by implication all waters whose submerged lands are not federally owned) were not subject to NPS regulation. The Court did acknowledge that federal subsistence fishing regulations applied on navigable waters within or adjacent to federal lands as a result of the outcome of the Katie John series of cases (Alaska v. Babbitt, 72 F.3d 698 (9th Cir. 1995)). In their acknowledgement, however, the Court refused to address federal subsistence fishing regulations since they were not at issue in Sturgeon II, leaving the Katie John rulings potentially open to future change.

This decision has rippling implications for the National Park Service in Alaska, as now their ability to manage the waterbodies that are protected within ANILCA-designated units is brought into question. NPS authority over these waters became a question of the ownership of their submerged lands following Sturgeon II. This ownership of submerged lands is in itself a complicated legal question with a long history rooted in ideas about state sovereignty.

As a sovereign, states hold title to the submerged lands of the navigable waters within their borders, a concept that relies upon the legal construct of navigability for title purposes to decide what is and isn’t navigable. Navigability for title purposes (which we will just refer to as navigability from here) has evolved over its history as court rulings have specified criteria and parameters defining its application. Waters are considered on a case-by-case and sometimes segment-by-segment basis based on these criteria to determine the ownership of their submerged lands and, post-Sturgeon II, who has the authority to manage them.

A Brief History of Navigability

Legal questions regarding the ownership of submerged lands based on their navigational use have a long history. In Roman law, a distinction was made between public and private submerged lands based on their use and on characteristics such as their ephemerality (MacGrady 1975). Within English common law, the sovereign (the monarch) owned the beds of all navigable waters as a means to ensure their use as highways for transportation and to ensure the sovereign’s authority to regulate and tax that use. As a consequence of English geography, specifically the lack of major navigable inland waterbodies, the definition of navigability in English common law was limited solely to tidally influenced waters as they were the only waters viable for this sort of use.

As subjects of the British Empire the American colonies operated under the legal system of English common law. Following independence, American law remained rooted in many English common law principles, and many of these principles and practices are recognizable within the American legal system today (Robbins Collection 2017). The strong emphasis on judicial precedent, the use of an adversarial system in which two opposing parties (a plaintiff and a defendant) compete before a moderating judge, and the use of a jury of ordinary people without legal training to decide on the facts of a case are all components of English common law that were carried over into the legal system of the United States.

Like many of these principles, navigability in American law extends from English common law. Within U.S. law navigability first arose as an issue of state sovereignty. In an 1842 case centered on a dispute over who possessed the right to harvest oysters in a certain bed in New Jersey, the Supreme Court ruled that the State of New Jersey held title to the lands beneath navigable waters in public trust as the sovereign successor to the English Crown (Martin v. Waddell, 41 U.S. 367 (1842)). This established the principle of state ownership of the submerged lands of navigable waters within the United States and affirmed it as an incident of state sovereignty.

Several years later in 1845, the case of Pollard’s Lessee v. Hagan (44 U.S. 212 (1845)) saw the application of the Equal Footing Doctrine to the question of navigability. The Equal Footing Doctrine is a principle in constitutional law that new states are admitted to the union on an “equal footing” with the original 13 states. Pollard’s Lessee v. Hagan concerned the ownership of the submerged lands between the shores of navigable waters within Alabama. The Supreme Court decided that the State of Alabama received title to these submerged lands upon statehood on an equal footing with the original 13 states.

Up until this point, in the U.S. the question of navigability was restricted solely to the submerged lands beneath tidally influenced waters just as it was within English common law. However, the 1851 case of The Propeller Genesee Chief v. Fitzhugh (53 U.S. 443 (1851)) brought this principle into question. The case concerned whether or not the federal government had admiralty jurisdiction over the nation’s rivers and lakes as well as its tidal waters. The Supreme Court held that the tidal waters doctrine of common law was not appropriate for American jurisprudence as the geography of the United States, with its many navigable inland rivers and lakes, was significantly different from that of England. The Court therefore rejected the tidal test as the sole qualifier of navigability and held that inland waters that were navigable in fact fall within federal admiralty jurisdiction. With the construct of navigability now expanded to include waters that are navigable in fact (versus just tidal waters) there subsequently arose a question of how to define “navigable in fact.”

This definition would come two decades later in the 1870 case of The Daniel Ball (77 U.S. 557 (1870)). In considering a question of interstate commerce and federal jurisdiction over it, the Supreme Court established what would become the classical definition of navigability:

Those rivers must be regarded as public navigable rivers in law which are navigable in fact. And they are navigable in fact when they are used or are susceptible of being used in their ordinary condition as highways for commerce over which trade and travel are or may be conducted in the customary modes of trade and travel on water.

This definition highlights several elements that must be considered when assessing navigability. The ruling established commerce (in the form of trade and travel) as the test for navigability. In other words, for a waterbody to be navigable it must have supported or been susceptible to supporting commerce. The susceptibility component indicates that there does not need to be an established history of commerce for a waterbody to be navigable so long as the characteristics of that waterbody indicate it could support such use. The definition also specifies that the waterbody must be in its ordinary condition, essentially stating that it could not have been modified to make it more or less navigable (such as by dredging or the construction of a dam). Further, this definition states that navigability is based on trade and travel upon water, therefore, use while frozen (for example a frozen river being used as a dogsled route) is not evidence of navigability. Finally, The Daniel Ball definition states that the commerce evidencing navigability must be conducted in the customary modes of trade and travel on water. This means that the waterbody must be capable of supporting commerce in crafts that would be typically used.

With the definition for navigability finally in place it was then refined over time. In 1874 in The Montello, the Supreme Court held that the presence of a portage along a waterbody did not render it non-navigable (The Montello, 87 U.S. 430 (1874)). In 1922, the Court ruled in Oklahoma v. Texas (258 US 574 (1922)) that waters that were only navigable during periods of spring flooding were not navigable for title purposes.

1953 saw the passage of the Submerged Lands Act (43 U.S.C. § 1301 et seq.), which codified the long-affirmed principle of state ownership of the submerged lands of navigable waters into statute and further refined the parameters of navigability.

The Act specified the time of statehood as the timeframe to be considered when determining navigability. That means that when considering evidence of navigability, the conditions of the waterbody at the time of statehood, as well as the types of crafts that would be customary at this time, must be considered. The Act also delineates the boundary of the submerged lands as being the line of the ordinary high-water mark (often taken to be the line of permanent vegetation for the sake of simplicity). Finally, the Act also specifies that title moves with instances of accretion, erosion, and reliction. In other words, title moves with the slow, natural migration of the meanders of a waterbody over time. However, title does not move in instances of avulsion, where the course of a river rapidly redirects.

The second half of the 20th century saw further refinement of the definition. The 1979 appeal of Doyon Ltd. to the Alaska Native Conveyance Approval Board offered several criteria specific to Alaska (ANCAB RLS 76-2, 86 I.D. 692 (1979)). The Board held that evidence of private use of a waterbody can demonstrate susceptibility, that poleboats, tunnel boats, and outboard motor-powered riverboats were customary crafts in Alaska at the time of statehood, and that present day recreational use can serve as corroborative but not definitive evidence of navigability. In 1983, the District Court for Alaska ruled that use of a waterbody for floatplane landings is not evidence of navigability (State of Alaska v. United States, 563 F. Supp. 1223 (1983)).

More recently, navigability was considered by the Supreme Court in the 2012 case of PPL Montana v. Montana (565 U.S. 576 (2012)). In this case, the Court established that modern recreational use could be evidence of susceptibility if it is proven to be meaningfully similar to customary use at the time of statehood. Perhaps more significant, however, was that the Court affirmed the practice of segmenting waters for navigability determinations.

We can then synthesize from this caselaw a definition of a navigable water as one that is actually used or is susceptible to being used as a highway for trade, travel, and commerce in the waterway’s natural and ordinary condition (at the time of statehood) in crafts customary at the time of statehood. Though far from comprehensive, this history demonstrates how navigability was and continues to be an evolving construct.

ALASKA DIGITAL ARCHIVES

Navigability Criteria

Now that we have a definition of navigable, we will take a closer look at some of the criteria for assessing navigability. A key component in the Daniel Ball definition of navigable is that the waterbody must be able to accommodate commerce. It is important, then, to consider what commerce would include. Generally, commerce in this context would be the existence of trade and travel across a waterbody. However, it is important to distinguish between commercial activity and boating in general.

An individual taking a canoe down a river on a recreational trip would not be an example of commerce, as it does not represent trade and travel. The simplest way to demonstrate that a waterbody was useful for commerce is to have clear historical evidence of trade and travel, for example photographs and written records of steamships transporting supplies or people on a river.

In many cases in Alaska however, no such historical record exists. Therefore, navigability becomes a question of the susceptibility for commerce rather than actual commercial use. In such instances, modern-day non-commercial activities can be evidence of navigability if it can be shown that the watercrafts employed are meaningfully similar to those that would have been customarily used for trade and travel at the time of statehood (PPL Montana v. Montana (565 U.S. 576 (2012)). We will elaborate more on what “meaningfully similar” means later, but for now we should maintain our focus on commerce.

A major consideration in assessing if an activity demonstrates commerce or the susceptibility for commerce is the weight in cargo a watercraft can transport. The issue of how much carrying capacity is necessary to constitute commerce is not an entirely settled legal question. In Alaska, the clearest guidance comes from the 1979 appeal of Doyon Ltd. (ANCAB RLS 76-2, 86 I.D. 692 (1979)). In this case, the board recommended that a net carrying capacity of 1,000 pounds could be used as a minimum threshold for commercial loads.

When examining evidence of commerce, another important consideration is whether there is a lack of actual use of a waterbody despite the conditions existing for that use. For example, if trade and travel commonly occur adjacent to a waterbody, but never actually make use of that waterbody to accommodate those commercial activities, that evidence would weigh against the waterbody being navigable (Oklahoma v. Texas, 258 U.S. 574 (1922)); Muckleshoot Indian Tribe v. FERC, 993 F.2d 1428 (9th Cir. 1993). However, the presence of an alternate route of commerce alone does not make a waterbody non-navigable.

VALDEZ MUSEUM

With a clearer understanding of how commerce is defined and interpreted in the context of navigability, we can now move to a discussion of customary crafts and meaningful similarity. The Daniel Ball definition specifies that commerce must be conducted in the “customary modes” of trade and travel on water. Because the time of statehood is the point in time being considered (as specified by the Submerged Lands Act) that means that “customary modes” would refer to watercraft that were customarily used in Alaska at the time of statehood on January 3, 1959.

Guidance on what types of watercrafts were customary in Alaska at the time of statehood comes from the 1979 appeal by Doyon Ltd. (ANCAB RLS 76-2, 86 I.D. 692 (1979)). The board found that pole boats, tunnel boats, and outboard motor-powered riverboats were customary crafts in Alaska at the time of statehood. If these types of crafts are capable of carrying a commercial load (at least 1,000 pounds) they could indicate that a waterbody was susceptible to supporting commerce at the time of statehood (and would therefore likely be navigable).

There has been some disagreement between the United States and the State of Alaska over what types of crafts were customary at statehood. For example, the U.S. has not agreed with the State that jet boats were customary at statehood based on their very limited availability in Alaska in 1959 (State of Alaska’s Mot. For Summ. J., Alaska v. United States, No. 3:12-cv-00114-SLG (D. Alaska 2015). During litigation over the Gulkana River, the court did not list jet boats as being customarily used on that river at statehood (Alaska v. United States, 891 F.2d 1401 (9th Cir. 1989)). If a waterbody is only traversable in modern crafts that are not meaningfully similar to crafts customary at statehood, then that waterbody would not be navigable (PPL Montana v. Montana (565 U.S. 576 (2012)).

With that being said, it is worth discussing what “meaningfully similar” means. In PPL Montana v. Montana (565 U.S. 576 (2012)) the court ruled that modern day, non-commercial use could be evidence of navigability if it can be shown that the crafts employed are meaningfully similar to crafts customary at the time of statehood. When assessing if a modern craft is meaningfully similar to a craft customary at statehood, a number of factors can be considered.

Just as weight capacity is an important consideration in determining susceptibility to commerce, it is also an important characteristic to examine when assessing if a modern craft is meaningfully similar to a customary one. If a modern craft is capable of carrying much greater loads than a customary craft of the same size, they likely would not be meaningfully similar. Additionally, draft requirements (or how far into the water a boat sits) are important to consider. If a modern boat capable of carrying commercial loads can be used in only a few inches of water while a customary boat requires deeper water to carry the same load, those two crafts would not be meaningfully similar.

In addition to weight capacity and draft depth, the material a craft is constructed from is also an important consideration. The materials used to construct inflatable rafts have made advancements since 1959. Therefore, modern inflatable rafts may be much more resistant to puncture and abrasion than inflatable rafts available at statehood. As such, these modern rafts would be able to traverse much shallower and rockier waterbodies than rafts at statehood likely could, thus the modern rafts likely are not meaningfully similar to rafts customarily used at statehood. Further, modern rafts often include features such as upturned bows and sterns as well as aluminum rowing frames that provide increased mobility—features that were not common on statehood-era inflatable rafts.

A watercraft’s means of propulsion is another important characteristic to consider when assessing a craft’s meaningful similarity to crafts customary at statehood. As noted earlier, there is dispute as to whether jet boats were customary at the time of statehood in Alaska. When compared to propeller-driven boats (which were certainly customary at the time of statehood) jet boats can be used in extremely shallow waters. Prop boats rely on a spinning propeller, which must stick further down into the water column to propel the craft. This spinning propeller runs the risk of striking objects along the bed of a waterbody and becoming damaged, which limits the boat’s ability to be used in shallow waters. In contrast, a jet does not need to stick as far down into the water and does not have a spinning propeller which can become damaged or tangled, enabling jet boats to be used in much shallower waters. Given this drastic difference in maneuverability, and the lack of widespread jet boats in Alaska at the time of statehood, this type of craft likely would not be meaningfully similar to a craft customarily in use at statehood.

Now that we have considered different questions about commerce and watercraft, we can move to a discussion about the characteristics of waterbodies themselves. As we noted earlier, historical evidence of commerce occurring on a waterbody is the most convincing evidence for navigability. However, in many if not most instances—particularly in Alaska where many waterbodies are remote and have no history of development—there is little to no historical record. In those instances, navigability becomes a question of susceptibility for use as a highway of commerce rather than actual documented use.

When considering susceptibility, we are often-times examining the physical characteristics of a waterbody and assessing if those characteristics would make it useful as a highway for commerce. The depth and gradient (slope) of a waterbody are both important physical characteristics to consider. There is no clear caselaw that establishes specific threshold values for what depths and gradients would make a waterbody navigable, and every waterbody is considered case-by-case based on its particular facts. However, if a waterbody were so steep that it couldn’t safely or reasonably accommodate trade and travel it very likely would not be navigable. Likewise, if a waterbody only had a depth of several inches and could not support a vessel carrying a load of cargo it very likely would not be navigable.

Another important physical characteristic to consider is the presence of obstructions along a waterbody that would inhibit travel, such as rapids, boulders, or log jams. The presence of obstructions does not automatically make a waterbody non-navigable. Though the presence of obstructions may make navigation quite difficult, if they can be reasonably portaged around and if the waterbody overall can still support trade and travel it may be navigable (Oregon v. Riverfront Prot. Assoc., 672 F. 2d 792 (9th Cir. 1982)). However, to be navigable the waterbody must still provide a route that is long enough to be useful and valuable in transportation (N. Am. Dredging Co. of Nev. v. Mintzer, 245 F. 297 (9th Cir. 1917)).

Alongside obstructions, it is also important to consider seasonality when assessing susceptibility. If a waterbody can only be navigated during periods of temporary high water, such as during seasonal floods, or if watercraft must be repeatedly dragged or carried the waterbody is likely non-navigable (United States v. Oregon, 295 U.S. 1 (1935)).

A final thing to note regarding susceptibility and physical characteristics is that a waterbody must be in its natural and ordinary condition at the time of statehood. This means that a waterbody cannot have been modified from its natural condition at the time of statehood to make it more or less navigable. If a waterbody could only be traversed after modification, for example by dredging, then it would not be navigable. Conversely, if a waterbody could have been traversed prior to statehood, but a dam was constructed post statehood that made it impassible, that waterbody could still be navigable since it is the natural and ordinary condition at the time of statehood that must be considered.

Navigability in Alaska: Implementation and Implications

Though the State of Alaska owns the submerged lands beneath navigable waters, there is an important exception: lands that were federally reserved at the time of statehood. If lands were reserved at statehood, and if the withdrawal included intent to reserve the submerged lands, those submerged lands remain in federal ownership regardless of navigability. This applies to the several pre-statehood parks in Alaska—portions of Denali, Katmai, Glacier Bay, and Sitka.

If there is no valid pre-statehood withdrawal for a waterbody, ownership of submerged lands (and jurisdiction over them) becomes a question of navigability. The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) is delegated the authority to make navigability determinations under the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (43 U.S.C. § 1701 et. seq.) and is the sole agency with authority to issue navigability determinations that have legal bearing. BLM does this as a part of the land conveyance process to avoid accidentally conveying State-owned submerged lands to another party.

When BLM makes navigability deter-minations, they consider the available historical evidence demonstrating a waterbody’s use as a highway for commerce. In the absence of historical evidence, BLM also considers the physical characteristics of a waterbody (such as depth, gradient, seasonal variability, and the presence of obstructions) and if those characteristics indicate that it would be susceptible to commerce.

Other agencies such as the NPS or the Alaska Department of Natural Resources may conduct their own research on navigability and publish those findings, but these assessments and any subsequent assertions of ownership and jurisdiction do not have legal bearing in the way that BLM determinations do.

There are two mechanisms for ultimately resolving title. The first of these is known as a Recordable Disclaimer of Interest, or RDI, and is an administrative process for clearing cloud on the title of submerged lands. As an administrative process, an RDI is intended to provide a mechanism for resolving cloud over title that is less costly and time consuming than litigation. The State can apply for an RDI through BLM by submitting a legal description of the claimed lands along with any evidence for navigability, and if the U.S. agrees with the evidence presented federal interest in the title is disclaimed. If BLM decides that the evidence for navigability presented within the RDI application is insufficient they may deny the application, at which point the State can appeal the decision to the Interior Board of Land Appeals—an appellate review body for the Department of the Interior.

In instances where the State chooses to not proceed with the RDI process, title can be litigated though what is known as a Quiet Title Action or QTA. The State can file a complaint in federal district court to adjudicate the issue of title to the submerged lands. To do this, the State must have grounds for their complaint such as the federal government taking a management action on State-claimed waters (for example the issuance of a BLM determination of non-navigable). Before the State may file a complaint, they must provide the United States with a 180-day notice of intent to file a Quiet Title Action.

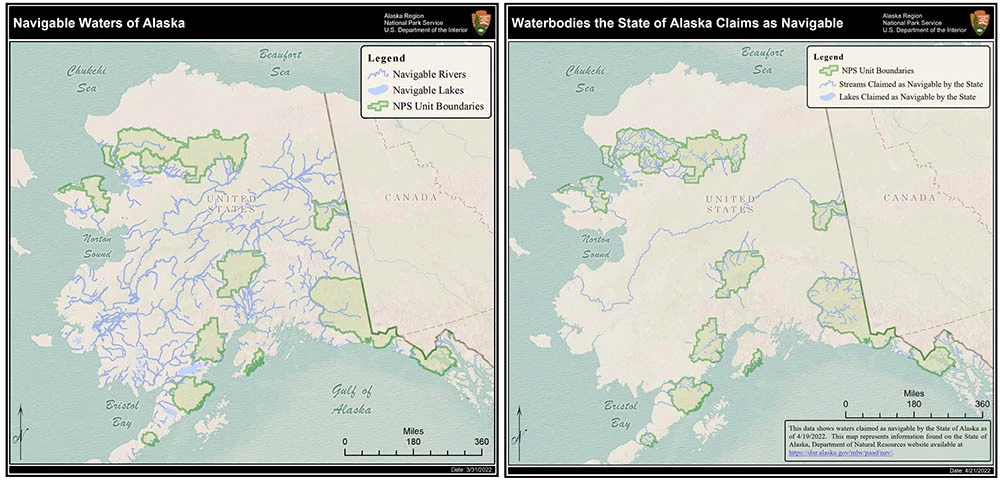

There is a contentious history of disagreement between states and the U.S. over navigability and Alaska is no exception. Following the outcome of the Sturgeon II decision, the State has become much more aggressive in asserting claims of ownership of submerged lands within federally protected areas. In 2021, it announced its “Unlocking Alaska” initiative in which Alaska has claimed ownership of nearly all waters within ANILCA-designated NPS units. In October of 2021 the State submitted a Notice of Intent to the U.S. to file a QTA for Twin Lakes, Turquoise Lake, and portions of the Mulchatna and Chilikadrotna Rivers within Lake Clark National Park and Preserve. In late April of 2022, the State of Alaska followed this up by filing a complaint within federal district court to quiet title to these submerged lands, thereby initiating litigation. In concert with filing for litigation, the State also submitted a notice of trespass to NPS for an NPS-owned dock on another waterbody within Lake Clark National Park and Preserve. Additionally, the State submitted a notice to cease and desist to the U.S. Forest Service for enforcing a regulation that prohibits the use of motorized watercraft on Mendenhall Lake.

Also, as a part of their initiative, the State of Alaska has released a web map that depicts most waters within CSUs as State owned, despite the lack, in most cases, of a BLM navigability determination or a final title resolution. This has the potential to mislead and confuse the public regarding whether these areas are subject to federal CSU regulations.

The outcome of Sturgeon v. Frost II has obscured the extent of the NPS’s regulatory authority over the waters within NPS CSUs in Alaska. There are now valid concerns over what activities may occur on waters within parks. Activities that are authorized under State regulations, such as suction dredge mining, could now occur within the boundaries of NPS CSUs (see ANILCA: A Perspective from Boots on the Ground). This management challenge is compounded by increasingly aggressive assertions of ownership made by the State. All of this has left the NPS in an uncertain position where land managers, in many cases, are not sure what they are able to manage, with no clear path forward on how to preserve these lands designated for protection by ANILCA.

References

Alaska v. United States, 891 F.2d 1401 (9th Cir. 1989)

Alaska National Interest Conservation Lands Act, 16 U.S.C. § 3103(c)

Federal Land Management Policy and Management Act, 43 U.S.C. § 1701 et. seq.

MacGrady, G. J. 1975.

The Navigability Concept in the Civil and Common Law: Historical Development, Current Importance, and Some Doctrines That Don’t Hold Water, 3 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 511. https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol3/iss4/1

Martin v. Waddell, 41 U.S. 367 (1842)

Muckleshoot Indian Tribe v. FERC, 993 F.2d 1428 (9th Cir. 1993)

N. Am. Dredging Co. of Nev. v. Mintzer, 245 F. 297 (9th Cir. 1917)

Nation and Kandik Rivers: Appeal of Doyon Ltd., ANCAB RLS 76-2, 86 I.D. 692, Dec. 14, 1979

Oklahoma v. Texas, 258 U.S. 574 (1922)

Oregon v. Riverfront Prot. Assoc., 672 F. 2d 792 (9th Cir. 1982)

Pacific Power & Light (PPL) Montana v. Montana, 565 U.S. 576 (2012)

Pollard’s Lesse v. Hagan et al., 44 U.S. 212 (1845)

Robbins Collection, Berkley Law 2017. The Common Law and Civil Law Traditions. https://www.law.berkeley.edu/research/the-robbins-collection/exhibitions/common-law-civil-law-traditions/

State of Alaska v. Babbitt, 72 F.3d 698 (9th Cir. 1995)

State of Alaska v. United States, 563 F. Supp. 1223 (D. Alaska 1983)

State of Alaska’s Mot. For Summ. J. at 23-25, Alaska v. United States, No. 3:12-cv-00114-SLG (D. Alaska June 1, 2015), E.C.F. No. 65

Sturgeon v. Frost, 577 U.S. ___ (2016)

Sturgeon v. Frost, 587 U.S. ___ (2019)

Submerged Lands Act of 1953, 43 U.S.C. § 1301 et seq.

The Daniel Ball, 77 U.S. 557 (1870)

The Montello, 87 U.S. 430 430 (1874)

The Propeller Genesee Chief, 53 U.S. 443 (1851)

United States v. Oregon, 295 U.S. 1 (1935)

Last updated: May 29, 2024