Part of a series of articles titled Commemorating ANILCA at 40.

Article

ANILCA: A Perspective from Boots on the Ground

Andee Sears has worked in Alaska parks since 1996. She was a park ranger at Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve, worked in subsistence at Denali National Park and Preserve, served as an investigator statewide, and currently oversees law enforcement and regulations for the region.

Adrienne Lindholm began her NPS career in 2000 as a backcountry ranger in Denali National Park and Preserve. She worked for Lake Clark National Park and Preserve and the Western Arctic National Parklands in backcountry planning and compliance before moving into her current position coordinating the Wilderness Stewardship program and Wild and Scenic Rivers program for the Alaska Region.

Peter Christian began his NPS career as a seasonal ranger in Denali National Park and Preserve in 1994. Peter’s ranger career took him to the Western Arctic Parklands (Cape Krusenstern National Monument, Kobuk Valley National Park, Noatak National Preserve, and Bering Land Bridge National Preserve), Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve, and Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve. Peter currently serves as the Regional Public Affairs Officer for the NPS Alaska Region.

NPS/JOSH SPICE

Many have called the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) the single most important piece of conservation legislation ever enacted.1 This idea has become firmly fixed in the National Park Service (NPS) canon in Alaska, and as we commemorate the 40th anniversary of ANILCA, it’s appropriate to recognize its successes.

On December 2, 1980, ANILCA created or added to thirteen national parks, sixteen wildlife refuges, two national forests, two national monuments, two conservation areas, and twenty-six wild and scenic rivers. It protected more than 104 million acres in Alaska, thereby enlarging the federal acreage for conservation in the state to 148 million acres. Nearly half of what was set aside—57 million acres—was designated wilderness, the highest level of protection for our federal public lands.

The ANILCA conservation system units are largely protected from permanent roads, industrial-scale tourism, logging, mining, oil and gas development, and damage from many types of access. The wilderness designation seeks to ensure that land managers approach decisions with humility and respect for the earth and its community of life, an approach that emphasizes values that are as essential to the well-being of our society today as ever before.

ANILCA’s recognition of subsistence2 serves as a model for balancing conservation and human uses on the landscape. Compared to many conservation laws, ANILCA clearly recognizes that these lands have been stewarded by Indigenous Peoples for tens of thousands of years. It assures the continued access to and use of traditional homelands by providing for the continuation of subsistence activities; reasonable access to subsistence resources; a preference for subsistence harvest over other consumptive uses; as well as for development, retention, and use of cabins and other structures to support subsistence uses.

The three authors, with a combined over 70 years of NPS field experience in Alaska, feel that it would be all too easy to mark the 40th anniversary of ANILCA by only highlighting ANILCA’s superlatives. Given significant developments in recent years, we think it is important to be candid about ANILCA’s challenges and shortcomings from an agency perspective.

In Do Things Right the First Time: An Administrative History of the National Park Service and the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (1985), then NPS historian G. Frank Willis3 presciently wrote:

Provisions protecting customary uses on conservation lands—access, cabins, subsistence—all seemed to hold the promise of future difficulties for managers from all agencies who were given too few, unclear, or contradictory directions for dealing with them.

Willis’ observation is an understatement relative to ANILCA and its implementation in Alaska over the past four decades.

While ANILCA put millions of acres of federal land into conservation system units, ANILCA is also rife with ambiguities, contradictions, and complexities that reflect the contentiousness of its passage. Agreement by members of Congress on the details both large and small was simply not possible. Congress left much to be resolved by federal land managers, the courts, or a future Congress. The consequence of not resolving ANILCA’s ambiguities is significant—inaction establishes a norm that is difficult to change.

After four decades, we think it is appropriate to reflect on ANILCA and how it has been implemented. Has it achieved its intended balance between use and preservation? Has ANILCA succeeded in providing for a subsistence way of life by those in rural Alaska? Has it given managers the tools to preserve natural resources, protect wilderness values, and provide for recreational opportunities?

This article offers a perspective understood by long time federal land managers in Alaska, but not often publicly discussed. We offer a discussion from our “boots on the ground” perspective, as we help parks with their everyday decisions. Many challenges faced by park managers intersect with state sovereignty issues: management of fish and wildlife, access across a large and relativity inaccessible state, and authority over navigable waters. In this article, we address these provisions of ANILCA that pose the most frequent and significant challenges for NPS: subsistence harvest and “sport” hunting, access methods that were “traditionally employed” by subsistence users, special access for “traditional activities,” the significant ramifications of the recent Sturgeon v Frost (Sturgeon II) ruling on navigable waters, and the complexities of managing wilderness according to rules found in no other state in the country.

The Promise of Subsistence

Providing rural residents the opportunity to continue their subsistence way of life is one of the primary purposes of ANILCA. Congress invoked its authority under the Property and Commerce Clause to make subsistence for rural residents the priority consumptive use for fish and wildlife resources.4 For the subsistence user and the land manager, however, the rules are exceptionally complicated. For millennia, people have been moving across the landscape interacting with the natural world, hunting, fishing, and harvesting its resources. The rules set in motion by ANILCA dictate who can engage in customary and traditional lifestyles, what tools and methods they can employ, and where and when they can do it. The interplay between various state and federal regulations has created a complex regulatory landscape that is challenging for users and managers to navigate.

In 1980, Congress envisioned the State of Alaska would implement ANILCA’s rural subsistence provisions and serve as the primary entity managing harvest of fish and wildlife on federal public lands. While it started out that way, it changed after Sam McDowell sued the State of Alaska arguing it was violating the State of Alaska Constitution by providing a preference for subsistence based on where one lives. The Alaska Constitution states “fish, wildlife, and waters are reserved to the people for common use”5 and further provides “use or disposal” of those resources applies “equally to all persons similarly situated…”6 McDowell argued providing rural residents a priority for harvesting fish and wildlife violated these provisions of the State of Alaska Constitution.7 The State Supreme Court agreed,8 forcing the State to decide whether to amend its constitution or have the federal government assume management of subsistence in order to effect ANILCA’s rural subsistence preference. After several years of debate, Alaska was unable to come to a consensus on amending the State Constitution, and a new regulatory entity—the Federal Subsistence Board9—was established to manage subsistence harvest of fish and wildlife on federal public lands under ANILCA.10 Importantly, the Federal Subsistence Board did not assert jurisdiction to regulate subsistence fishing on navigable waters.

PHOTO COURTESY OF AHTNA, INCORPORATED

Predictably, the legal conflict over subsistence shifted to fishing a few years later. Two Ahtna Athabascan elders, Katie John and Doris Charles, sued the Department of the Interior, arguing the federal government had an obligation to provide for a rural subsistence priority for harvest of fish, as well as wildlife. This led to a series of decisions, collectively referred to as the Katie John cases, from the Ninth Circuit11 that remain controversial today.12 The Ninth Circuit agreed with Katie John and Doris Charles that ANILCA’s rural subsistence priority also applies to fishing on “public lands,” a term defined by ANILCA.13 [Also see Alaska Native Rights Champion Katie John Lived What She Believed.] In short, this term means lands, waters, and interests which are federally owned.14 As discussed later in this article, lands beneath navigable waters are owned by the State of Alaska in most cases.15 Waters are not subject to traditional ownership principles; rather, the law recognizes the right to reserve waters for use.16 The Ninth Circuit found that when Congress set aside conservation system units in Alaska, it also reserved (by implication) waters necessary to achieve ANILCA’s purposes, one of which is subsistence.17 Accordingly, those reserved waters within and adjacent to conservation system units are “interests” to which the United States has “title,” which makes those waters fall within ANILCA’s definition of “public lands.”18 As “public lands” under ANILCA, the Ninth Circuit’s decision obligated the federal government to provide a rural subsistence priority on those waters in absence of the State doing so.19 This led to the expansion of the Federal Subsistence Board’s role to manage subsistence fishing as well as harvest of wildlife.20

The Katie John decision remains controversial today. Many Alaskans wanted the Governor to request review by the U.S. Supreme Court.21 Many Alaskans wanted to amend the State Constitution in order to return management of subsistence under ANILCA to the State.22 Neither has happened. The result is a complex management scheme involving the State of Alaska, the Federal Subsistence Board, and individual bureaus like the National Park Service.23 As a subsistence user or a federal land manager, it requires navigating regulations from all three entities, and understanding the interplay between the three sets of rules when there is a gap or a conflict between them. It is far from simple and there is nothing on the horizon indicating future simplification. Does this regulatory framework succeed in achieving Congress’s direction to “provide the opportunity for rural residents engaged in a subsistence way of life to continue to do so”?

Wildlife Regulations and “Sport” Hunting in National Preserves

In addition to rural subsistence harvest (now regulated by the federal agencies post-McDowell), ANILCA authorizes “sport” hunting and trapping in national preserves under state law as long as it is consistent with federal law and regulations. Decades ago, however, the State dropped the term “sport” from their hunting regulations and instead uses the terminology “general” and “subsistence” hunting. This change in terminology causes considerable confusion on the ground since subsistence under ANILCA’s provisions is federally managed and limited to rural residents. Hunting in national preserves under state subsistence regulations actually falls under ANILCA’s “sport” provisions.24 In short, when regulators (or the public) refer to subsistence, it is often unclear whether they are referring to federal subsistence under ANILCA (which is limited to rural residents) or state subsistence (which post-McDowell is available to all Alaska residents—whether they live in a rural or urban setting).25

NPS PHOTO

ANILCA’s stated intent is that national preserves be managed in the same way as national parks—consistent with the NPS mission—with the exception that sport hunting and trapping are allowed. The State rejected these requests and declined to accommodate the different management objectives for NPS national preserves, saying that they manage wildlife populations in Alaska regardless of who owns or manages the land on which those populations are located.26 On the ground, this meant liberalizing hunting practices for predator species in order to reduce predation predominantly on moose and caribou.27 The ANILCA conflict that erupted concerned management of parks and preserves—where the NPS strives for natural wildlife abundances and diversity28 and the State’s goal to manage wildlife to support “a high level of human harvest of game[.]”29 NPS sought to avoid this conflict by requesting the State exclude national preserves from some specific harvest practices—taking bears over bait, taking bear cubs and sows at den sites with artificial light, and extending the season for taking wolves and coyotes (including pups) when pelts have little value.30 The State rejected these requests because it is the State’s view that it manages wildlife populations in Alaska regardless of who owns or manages the land where those populations are located.31

NPS took action in 2015 to achieve the same result—to exempt national preserves in Alaska from these harvest practices—through federal rulemaking. This rule, specific to “sport” hunting and trapping, relied on the following clause in ANILCA to restrict these harvest practices “within national preserves the Secretary may designate zones where and periods when no hunting, fishing, trapping, or entry may be permitted for reasons of public safety, administration, floral and faunal protection, or public use and enjoyment.”32 Despite this statutory provision, the State argued that the NPS exceeded its authority in adopting these restrictions and that such restrictions must be predicated upon biological data33 demonstrating potential to impact the sustainability of the population.34

A change in the federal administration resulted in a reversal of that position. In 2020, the Department of the Interior (DOI) published a second rule rescinding the 2015 rule, determining such hunting practices can be allowed in national preserves in Alaska consistent with federal law and exercised its discretion to do so. Controversy, including litigation, over whether such practices are consistent with federal law and policy for national preserves continues.35 This conflict could have been avoided in multiple ways: (1) Congress could have included a definition of “sport” hunting in ANILCA with respect to harvest in national preserves, (2) they could have been more clear in providing NPS authority to restrict state-authorized harvest practices in order to maintain natural abundances in a naturally functioning ecosystem, or (3) they could have provided for exclusive management to the State rather than recognizing federal authority to regulate wildlife harvest in national preserves.

ANILCA’s Overlapping Access Provisions

Providing an opportunity for subsistence users to continue their way of life depends on ensuring reasonable access to hunting and fishing areas. To that end, Congress authorized “snowmobiles, motorboats, and other means of surface transportation traditionally employed” including in designated wilderness.36 The issue that comes up repeatedly for managers regarding this provision of ANILCA is whether All-Terrain Vehicles (ATVs also referred to as Off-Road Vehicles or ORVs) are allowed in those areas open to subsistence. It does appear that ATVs are “other means of surface transportation,” but it is less clear whether they were “traditionally employed,” especially since ANILCA again does not define this key term. Is the term given meaning at the time ANILCA was passed? In other words, must a specific method of access have been “traditionally employed” in 1980? Or, does an agency have discretion to allow a method of access that wasn’t an established or “traditional” in 1980—including in wilderness—but has since developed, perhaps through unauthorized use? And how should evolving technologies be accommodated? The four-wheelers and side-by-side utility vehicles that are common in many places today have evolved considerably from the types of vehicles that were capable of off-road use in the years preceding ANILCA.

Left: Pre-1980 off-road vehicle. (PHOTO COURTESY OF RAY BANE)

Right: Modern off-road vehicles. (NPS PHOTO)

NPS/KEVIN MEYER

Shortly after ANILCA was passed, many parks used management plans to review whether ATVs were traditionally used for subsistence. Given the limited availability and use of these types of vehicles, it is not surprising that the NPS determined in almost all cases they were not “traditionally employed.”37 As technology evolved and ATVs became more affordable, there has been interest in revisiting those determinations.38 Given the ambiguity regarding this access authorization and the fact that ATV use is not generally allowed in parks, it is a challenge for land managers to navigate in a manner that is consistent with the law and also supportive of opportunities to continue a subsistence way of life. In those areas where ATV use has been determined to be “traditionally employed” or has otherwise become an established use, one can’t overlook that ATVs have an unmistakable impact on the landscape.39

The “Special Access” provision40 of ANILCA is another authorization for access that challenges NPS managers. This authorization applies in all conservation system units, which is defined by ANILCA to include all NPS units, including wilderness and units that predate ANILCA. In this provision, Congress authorized “snowmachines…, motorboats, airplanes, and other means of nonmotorized surface transportation for traditional activities… and travel to and from villages and homesites[.]” This authorization applies in all conservation system units (which incudes all NPS units in Alaska), including designated wilderness and units that predate ANILCA. Note that the language partially overlaps with the subsistence access section, but there are important differences. First, this provision does not require the person engaging in the “traditional activity” to be a rural subsistence user. Second, the qualifier on whether a method is authorized is not based on whether the specific method was “traditionally employed” but rather whether it is being used to support a “traditional activity” or “travel to and from villages and homesites.” Third, it does not authorize ATVs since surface transportation methods are limited to nonmotorized means.

NPS PHOTO (LEFT), PHOTO COURTESY OF BOB RANEW (RIGHT)

The ambiguity introduced by ANILCA’s undefined term “traditional activity” is a primary source of NPS management challenges. For example, is it lawful to use a snowmachine to access a mountaineering route on Mount Sanford, a 16,237-foot mountain in Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve popular with climbers? What is the activity that managers should analyze to determine if it falls within ANILCA’s authorization for snowmachines for “traditional activities:” (1) use of the snowmachine, (2) recreational mountain climbing, or (3) recreation in general? If recreation generally is the activity evaluated under this provision of ANILCA, what activities are not included in this “special” access provision?41 Would such a broad interpretation allow snowmachines on all NPS lands, including wilderness, in Alaska? And if so, why was the qualifier of access for “traditional activities” even included in the statutory authorization? Would this really be consistent with Congress’ authorization for “special” access? There are no definitive answers to these questions. In the absence of an answer in ANILCA, NPS has generally adopted a management stance accommodating a broad view of what would be included as a “traditional activity.”42

PHOTO COURTESY OF ERIC PARSONS

Waters and Navigable Waterways

Until 2019, NPS managed waters within Alaska parks similar to the surrounding federal uplands, as is done elsewhere in the National Park System.44 On the ground, this meant that if a park was closed to hunting, individuals were not allowed to hunt from a river within the park below the high-water line. It meant that NPS regulations pertaining to vehicle and vessel use, fuel and property storage, hunting and fishing, solid waste disposal, mining, and other activities applied to these waterways regardless of who owned the submerged lands. The State of Alaska and some user groups however, argued that ANILCA precluded NPS from exercising regulatory authority over navigable waters, pointing to section 103(c) of ANILCA:45

Only those lands within the boundaries of any conservation system unit which are public lands (as such term is defined in this Act) shall be deemed to be included as a portion of such unit. No lands which, before, on, or after the date of enactment of this Act, are conveyed to the State, to any Native Corporation, or to any private party shall be subject to the regulations applicable solely to public lands within such units. If the State, a Native Corporation, or other owner desires to convey any such lands, the Secretary may acquire such lands in accordance with applicable law (including this Act), and any such lands shall become part of the unit and be administered accordingly. (emphasis added)

NPS long understood its regulation of waters as not being barred by section 103(c) since they do not apply “solely” to federal public lands within the parks—rather, NPS regulations applied regardless of ownership of the submerged lands.46 NPS also pointed to the numerous references in ANILCA regarding protection of waters47 and the fish and wildlife that depend on them, express authorization in ANILCA to regulate boating and fishing, as well as the Katie John precedent discussed above.48 The U.S. Supreme Court, however, was unpersuaded by the NPS interpretation of 103(c).

NPS PHOTO

At issue in Sturgeon v. Frost, was a moose hunter who sought to use a hovercraft on the Nation River within Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve. Hovercraft are not allowed within parks under NPS regulations.49 The Nation River is navigable and the submerged lands are owned by the State.50 In rejecting the NPS interpretation of section 103(c), the Supreme Court ruled that NPS regulations did not apply to activities on waters because neither the submerged lands nor the water itself was federally owned.51

On its face, some believe the Sturgeon II decision is or should be narrowly confined to the facts before the court: use of hovercraft on a navigable waterbody where ownership of submerged lands is confirmed to the State. However, the basis of the court’s decision hinged on a broader interpretation of the law—that NPS can only regulate activities on (or in the case of waters, over) federally owned lands. For this reason, the most appropriate implementation of the law extended the Court’s ruling to other NPS regulations besides the hovercraft rule. That said, the interpretation of section 103(c) adopted by the court has far-reaching impacts and has introduced widespread ambiguity on what activities are allowed or not, and what rules apply where, and will likely take many decades to resolve. For example:

- Can a Wasilla hunter hunt moose along the Chitina River in Wrangell-St. Elias National Park, an area only open to subsistence harvest by rural residents?52

- Will a Fairbanks gold miner be able to operate a suction dredge in the Wild and Scenic Charley River in Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve?53

- Should an Anchorage resident who has a summer home on Lake Clark be able to harvest salmon in the lake with a net?54

- Can an out-of-state hunter harvest swimming caribou in the traditional Native hunting area at Onion Portage in Kobuk Valley National Park?55

- Are visitors from out of state eligible to drive ATVs along gravel bars within Denali National Park?56

- Is it permissible for the State of Alaska to conduct aerial wolf control on the frozen Yukon River in Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve?57

PHOTOS COURTESY OF KATHY WADE (LEFT) AND PETER CHRISTIAN (RIGHT)

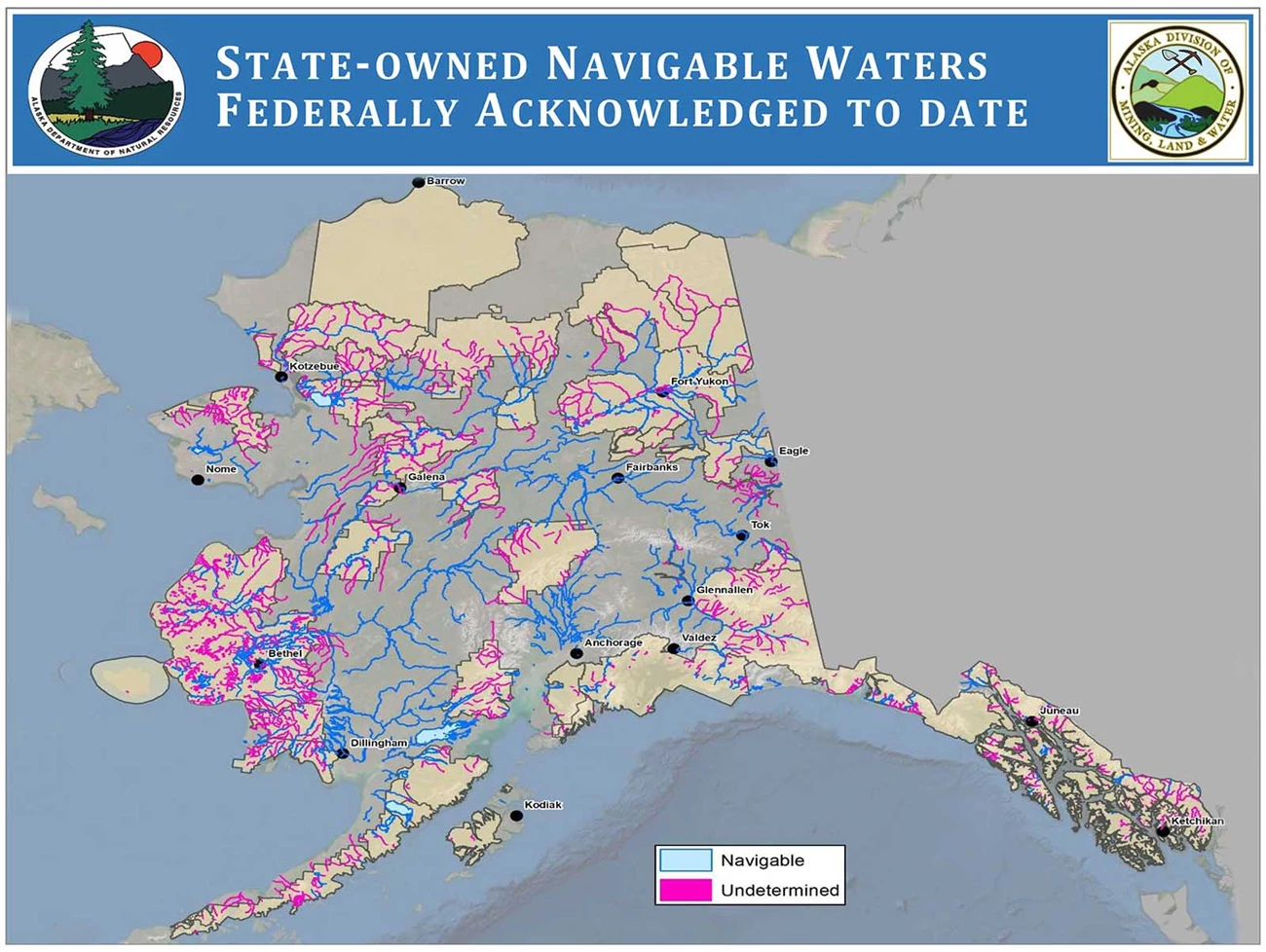

The current NPS position is clear—these activities are not precluded by NPS regulation if the submerged lands are not federally owned.58 The problem facing federal land managers and the public is a definitive answer on who owns the submerged lands. While it is a question of federal law to be settled by federal authorities, the State of Alaska has made and published its own assertions of navigability/ownership59 which has resulted in confusion on who owns submerged lands and who has authority to make such determinations.60 How should these uses be managed in the absence of such an ownership determination, in particular in the absence of a federal determination?

Ownership of submerged lands depends on navigability, which is based on historical use and the physical characteristics of the waterbody at the time of statehood (1959 for Alaska).61 Further, these determinations are made on a case-by-case and segment-by-segment basis.62 Depending on the remoteness of the waterbody (or more precisely, the segment), documenting the physical characteristics can take months and cost tens of thousands of dollars.63 Prior to Sturgeon, NPS didn’t seek to determine who owned the submerged land when managing, regulating, and enforcing park rules. Post-Sturgeon II, the primary question confronting NPS managers is whether any given waterbody is navigable. (Also see: ANILCA, Navigability, and Sturgeon)

The circumstance that complicates the Sturgeon II decision more than the justices were surely aware, is that ownership of the submerged lands below most waters within the 54 million acres of NPS-managed lands is unknown. Indeed, within parks in Alaska, there are more than 100,000 miles of rivers and more than one million acres of lakes. Of these waters, title is only settled in the pre-statehood portion of Glacier Bay and fewer than a dozen water segments—one of which is the Nation River, at issue in the Sturgeon case.64

It will likely take many decades to resolve ownership of submerged lands. So, what does management look like in the meantime? Consider the list of examples above. Should NPS manage all waters without a federal navigability determination as though they are federally owned in the interim? Or should NPS adopt the opposite approach, taking a hands-off stance absent a federal determination that the United States holds title to the beds? The best approach is a collaborative agreement on interim management with the State. However, on March 26, 2021, Alaska asserted State jurisdiction over many waters within NPS areas that lack a federal navigability determination, making the liklihood of such an agreement unlikely.65 Additionally, State officials are actively encouraging the public to engage in activities on these waters as though they are not subject to NPS regulation.66 For those members of the public seeking to avoid being caught in the legal fray, how should NPS managers respond to their inquiries on what they can and can’t do? Whose rules apply to specific waters? Is the response to the public that they are assuming risk with legal consequences if they choose to engage in an activity that is not consistent with NPS regulations and it turns out the area is federally owned? If it is not federally owned, how many people would be deterred from doing something that turns out to be legal? What is the liability risk to the agency and individual employees if they enforce NPS rules in an area that is later determined to be nonfederal land? On the other hand, what are the consequences of failing to protect lands and resources in areas later determined to be federally owned and part of the National Park System? How does ANILCA, as it is currently understood, ensure proper stewardship of land and waters within conservation system units in Alaska?

MAP PREPARED BY THE STATE OF ALASKA

ANILCA’s Unique Wilderness

The primary mandate of the 1964 Wilderness Act is to preserve wilderness character by ensuring protection of the undeveloped, natural, and untrammeled qualities of wilderness, opportunities for solitude or primitive and unconfined recreation, as well as other features of value. Recognizing the vast undeveloped landscape in Alaska, ANILCA directed agencies to apply the same high standards for preservation as mandated by the 1964 Wilderness Act while simultaneously allowing special provisions that accommodate things like motorized transportation methods and facility development. ANILCA was not meant to wholly supplant the Wilderness Act, but rather make exceptions where necessary based on Alaska’s remote environment and large size. The main challenge for federal wilderness stewards in Alaska is to preserve wilderness character in light of the several allowances (e.g., snowmachines) not usually allowed in wilderness. On paper, ANILCA provides federal land managers tools for achieving the delicate balance between protecting resources, subsistence opportunities, and other public uses.67 However, from a practical standpoint, it is often not politically feasible for managers to use these tools. The on-the-ground consequence is that ANILCA’s ambiguities are often resolved in the direction of compromising resource protection.68

The ambiguities of ANILCA provisions related to special access, subsistence access, waters, cabins, and temporary structures have created enough uncertainty that they prevent land managers from curtailing uses that degrade wilderness character. When it comes to wilderness rivers in particular, Sturgeon II created a complex network of state inholdings everywhere a navigable waterbody flows. The Noatak River, the Alatna River, the Charley River, even Lake Clark itself, and many other waterbodies, have now become problematic for federal managers. What is Lake Clark National Park without Lake Clark? What is the Noatak Preserve without the Noatak River? After the Sturgeon II decision, wilderness areas that once seemed so large and unbroken are now functionally fragmented by every river and waterbody without a federal navigability determination. Such fragmentation makes it difficult, if not impossible, to protect an intact ecosystem when the area is sliced into smaller pieces.

If Alaska’s wilderness areas are fragmented by navigable waters, have mechanized and motorized uses occurring throughout them, and are degraded by actions like predator control that aim to manipulate wildlife populations; what makes Alaska wilderness different from other public lands? These challenges present significant barriers for wilderness managers to preserve.

The Next 40: Options for Stewarding Parklands in Alaska Under ANILCA

We realize we have raised a number of significant issues and management challenges posed by ANILCA, highlighting how it currently plays out on the ground. We see three options for how parklands in Alaska are stewarded for future generations: (1) accept the status quo, (2) managers can “fill the gaps” and attempt to resolve some of the conflicts created by the law, or (3) Congress steps in with new legislation to resolve ambiguity and conflicts.

The Status Quo

The status quo option means continuing to struggle with the ambiguities, uncertainties, and conflicts discussed in this article. For subsistence, rural residents and managers will continue to muddle their way through the complex network of regulations pertaining to harvest that are adopted by several agencies with overlapping authority, sometimes in a manner that is not consistent with the federal law. For harvest of wildlife outside of Title VIII, “sport” hunting includes essentially any state authorized harvest activity, whether it is state subsistence, recreational hunting, or trophy hunting. It means an out-of-state recreational hunter can harvest a swimming caribou alongside a rural subsistence user. It means a hunter seeking a trophy can use dog food as bait to attract a brown bear. It allows a Fairbanks resident to harvest a black bear sow with cubs in the den just like a rural subsistence user engaging in a customary and traditional practice.

On access, it means ORVs are likely to become more common and penetrate deeper into parklands, likely bringing with it biophysical and visual impacts to the landscape. For “special access,” it means snowmachines will likely be used throughout parks69 for any given number of activities. Motorboats, airboats, bicycles, and airplanes will remain broadly allowed in all parks in Alaska, including wilderness.

With respect to waters inside parks, it means for many years to come, no one will know what rules apply to most waterways, what activities are authorized, who to get permission from or even to whom to direct questions. Given this lack of clarity, it means new uses, some incompatible with how parks are managed, will become established. When ownership is finally resolved, only then will it be clear whether the use was appropriate or whether NPS must contend with an incompatible but now established use, something that has been proven over time and in many locations across the NPS to be exceptionally difficult to effectively address.

Fill the Gaps

Another option is for managers to “fill the gaps” where Congress left ambiguity and resolve conflicts to the extent permissible with administrative authority. Under this option, few changes are possible to address the challenges discussed for subsistence, however. As long as multiple agencies have management responsibilities, the regulatory landscape will be complicated. Ideally federal and state managers should work together to simplify and streamline rules to the extent possible. It would be naïve, however, to assume that a collaborative approach is feasible and would result in any real improvements. This reflects a number of factors—how far apart the state and NPS often are on many of these issues and more generally, the anti-federal (and specifically anti-NPS) sentiment prevalent in the state.70 It also reflects the reality of multiple regulatory bodies having unique statutory missions (which drives different courses of agency action).

For harvest of wildlife outside of Title VIII, a range of options exist—assuming the status quo is not desired. NPS could define the term “sport hunting” and/or adopt regulations that outline specific practices that are (or are not) consistent with the term. Like the 2015 regulations mentioned above though, using administrative authority is likely to result in litigation or political pressure on managers rendering administrative action difficult and possibly infeasible.

For the access conundrum, NPS could, for example, adopt regulatory definitions of key terms like “traditional activities” and “traditionally employed,” tiering off the definition of “traditional” adopted in general management plans in the mid-1980s for several parks. Under the definition in these plans, “a ‘traditional means’ [under 811(b)] or ‘traditional activity’ [under 1110(a)] has to have been an established cultural pattern… prior to 1978 when the unit was established.”71 This would resolve much of the ambiguity created in 1980 surrounding these authorizations. However, these terms are used in reference to a variety of federal conservation lands in Alaska under charge of several federal entities, raising the issue of whether the various agencies should and can agree on a meaning. Additionally, since 1980, access methods authorized under ANILCA have become more common and more established, particular in the absence of any meaningful sideboards. If NPS seeks to adopt definitions that curtail uses and it is less than clear that the agency will be to carry it out due to political pressure. Additionally, a decision under one administration might be overturned or changed by the next one, as we have recently seen in several instances.72

With regard to waters, the Court’s interpretation section 103(c) leaves few options for the NPS to resolve ambiguity over management of activities on waters within Alaska parks. One potential option is for the NPS to adopt administrative standards to identify which waters NPS will or will not manage in the absence of a federal determination on navigability or ownership of submerged lands. Alternatively, NPS could unconditionally accept the State’s navigability assertions as the basis for management (or lack thereof)—unless and until determined otherwise by a competent federal authority. The problem with the latter approach is the same as mentioned above: new uses not necessarily compatible with how parks are managed may become established, causing potentially irreparable harm if those areas are later determined to be federal. Further, once those uses are established, history shows it is difficult at best to curtail them.

Legislation

A third option is new legislation to address some of the ambiguities created in 1980 and challenges that have cropped up since. Legislation could simplify the subsistence regulatory framework and it could modify or expand subsistence opportunities. It could define key terms that have important bearing on wilderness management, such as “traditional activities.” It could also clarify for the public and managers how waters should be managed within park areas, a conflict the NPS has limited authority to address on its own. We recognize the likelihood of persuading a majority of Congress on a matter specific to a single state, and specifically one that is likely going to be controversial, is slim. There is also the possibility that legislation may create more ambiguities and conflicts than currently exist, potentially resulting in more impacts to resources and values of parklands in Alaska. However, legislation is likely the only viable way to address the problems created by the Sturgeon II decision and if resolution is desired on the other topics discussed above, the only practical option.

Conclusion

With respect to the size and scale of lands set aside, ANILCA is appropriately considered a highwater mark for conservation in North America. It protects largely intact ecosystems on an unprecedented scale in the United States. ANILCA parklands provide settings for life-altering experiences. They provide opportunities for the most remote and extreme wilderness adventures. They offer unique and unparalleled hunting opportunities. They provide settings for spiritual well-being and renewal, serve as an economic driver for the State of Alaska, inspire educators and artists, and help protect traditions for Alaska Native people. Parklands also stand as a more equitable model for environmental protection by providing a lens for rightly viewing parks and wilderness areas as places with long and complicated human histories.

We also recognize and acknowledge ANILCA’s challenges and shortcomings. ANILCA introduced numerous ambiguities and conflicts. Implementing ANILCA has led to an extraordinarily complex regulatory patchwork difficult for the public and land managers to navigate. On the ground, ANILCA’s ambiguities and conflicts are often resolved in the direction of compromising resource protection. Reflecting on these realities, we question whether ANILCA struck the right balance between use and preservation. Has it succeeded in protecting Alaska Native customary and traditional ways of life? Does ANILCA truly provide land managers with the tools they need to protect existing uses while also preserving wilderness character? Did Congress really intend to allow motorized access for any activity in wilderness? Is it appropriate that waters within parks in Alaska are cherry-stemmed, fragmenting the units into many small pieces, introducing new uses incompatible with how NPS-managed uplands are protected? Given Sturgeon II, what will future courts decide about protection of wild and scenic rivers within federal conservation areas in Alaska? Did Congress really intend to pass legislation for national interest conservation system units that exclude many rivers, streams, lakes, riparian zones, and biological hot spots from protection? Will land managers be able to keep the promise of federal subsistence on waters within conservation units?

Under the current trajectory, federal land managers face rough waters for ANILCA’s next 40 years. Should managers—and more importantly, Congress and the American people—continue to accept ANILCA’s ambiguities and complexities along with the resultant consequences to resources, visitor experience, and subsistence? The easiest option is for managers to take no action to resolve these challenges; in other words, postpone actions and decisions, hoping to maintain the status quo. The effect of individual decisions, or lack thereof, may not be immediately felt, but the cumulative result becomes apparent over time: recreational use of snowmachines and airboats become established and accepted in Alaska wilderness, jet skis on Lake Clark, proliferation of ORVs with their resultant impacts, suction-dredge mining on the wild and scenic Charley River, gravel extraction below ordinary high water, sport hunting along waterways within national parks, and resource fragmentation and degradation that continue to eat away at the wild Alaska supposedly protected for the national interest.

We believe the current path is not consistent with the objectives and congressional record of ANILCA. Land managers could attempt to fill the statutory gaps by defining key terms, promulgating new regulations, or working to resolve conflicts through a cooperative management approach with stakeholders. While such an approach is within the agency’s authority, it would be misleading not to acknowledge the difficulty—which could be insurmountable— of addressing high stakes controversial matters involving public use for the reasons mentioned above.

NPS is largely on the status quo path. We believe legislation is the only way to effectively address activities on waters within park units post-Sturgeon. We also believe that it is likely the only effective option for addressing many of the other challenges discussed in this article. However, even if Congress has the will to consider legislation, this approach does not come without risk and would not satisfy all interests. National and local interest groups will undoubtedly be highly interested and aggressively lobby to strengthen or weaken various provisions in the Act. Given the polarized and entrenched positions on land management in Alaska, it is likely that whatever comes out the other side of a legislative “fix” could create even more challenges for resource protection and for public land stewardship. The alternative is leaving unfinished business still undone, and a failure to safeguard the commitment to Alaska’s subsistence community or to the responsible stewardship of the national interest—promises made by ANILCA forty years ago.

END NOTES

1 Celebrating 35 Years of ANILCA (Dec. 2, 2015), https://trustees.org/celebrating-35-years-of-anilca/; https://alaskaconservation.org/about/people/board-directors/ (last visited June 29, 2021); Williams, D., The National Action Imperative to Achieve 30 by 30, (May 2, 2021), https://thehill.com/opinion/energy-environment/554819-achieving-30-x-30-climate-action-requires-national-and-local.

2 The term “subsistence uses” as used in ANILCA means “the customary and traditional uses by rural Alaska residents of wild renewable resources for direct personal or family consumption as food, shelter, fuel, clothing, tools, or transportation; for the making and selling of handicraft articles out of nonedible byproducts of fish and wildlife resources taken for personal or family consumption; for barter, or sharing for personal or family consumption; and for customary trade.” ANILCA § 803, codified at 16 U.S.C. § 3113.

3 Willis’s administrative history on ANILCA is widely regarded within NPS as the best source of agency history on ANILCA. G. FRANK WILLISS, “DO THINGS RIGHT THE FIRST TIME”: THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE AND THE ALASKA NATIONAL INTEREST LANDS CONSERVATION ACT OF 1980, (National Park Service) (1985) available at https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/williss/adhi.htm.

4 The Act provides that “the taking on public lands of fish and wildlife for nonwasteful subsistence uses shall be accorded priority over the taking on such lands of fish and wildlife for other purposes. . . .” ANILCA § 804, codified at 16 U.S.C. § 3114.

5 ALASKA CONST., art. VIII, § 3.

6 ALASKA CONST., art. VIII, § 17.

7 McDowell v. State, 785 P.2d 1, 2 (Alaska 1989)

8 Id. at 8.

9 50 C.F.R. § 100.10(b).

10 Temporary Subsistence Management Regulations for Public Lands in Alaska, 55 Fed. Reg. 27,114 (June 29, 1990). See NORRIS, F., ALASKA SUBSISTENCE: A NATIONAL PARK SERVICE MANAGEMENT HISTORY, at p. 165 (Sept. 2002), available at https://www.nps.gov/subjects/alaskasubsistence/upload/Norris_For_Web.pdf.

11 Alaska v. Babbitt,72 F. 3d 698 (1995); John v. United States, 247 F. 3d 1032 (2001) (en banc); John v. United States, 720 F. 3d 1214 (2013) (Katie John cases).

12 See, e.g., Anderson, R. The Katie John Litigation: A Continuing Search for Alaska Native Fishing Rights After ANCSA. 51 Ariz. St. L.J. 845 (2019). Wohlforth, C., Opinion: The Kavanaugh Supreme Court appointment would threaten Alaska Native subsistence, ANCHORAGE DAILY NEWS, (Aug. 14, 2018), available at https:// www.adn.com/opinions/2018/08/14/the-kavanaugh-supreme-court-appointment-would-threaten-alaska-native-subsistence/.

13 Alaska v. Babbitt, 72 F.3d 698, 703-04 (9th Cir. 1995).

14 Id. at 701-02 (citing ANILCA § 102, codified at 16 U.S.C. § 3102).

15 See Sturgeon v. Frost, 139 S.Ct. 1066, 1074 (2019) (Sturgeon II).

16 Id. at 1078.

17 Alaska v. Babbitt, 72 F.3d at 703.

18 Id. at 703-74.

19 Id.

20 Subsistence Management Regulations for Public Lands in Alaska, 64 Fed. Reg. 1276 (Jan. 8, 1999).

21 Miller, H. K., On the Passing of Ahtna Elder, Katie John, INDIAN COUNTRY TODAY, (June 13, 2013), available at http://indiancountrytoday.com/archive/on-the-passing-of-ahtna-elder-katie-john; Norris, F., ALASKA SUBSISTENCE: A NATIONAL PARK SERVICE MANAGEMENT HISTORY, at p. 247 (Sept. 2002), available at https://www.nps.gov/subjects/alaskasubsistence/upload/Norris_For_Web.pdf.

22 Knowles Seeks Again to Resolve Decade-Long Subsistence Impasse, ALASKA JOURNAL OF COMMERCE, (Feb. 24, 2002) available at https://www.alaskajournal.com/community/2002-02-25/knowles-seeks-again-resolve-decade-long-subsistence-impasse; Subsistence Amendment Introduced by Knowles, SITNEWS -STORIES IN THE NEWS, (Feb. 14, 2002) available at www.sitnews.org/0202news/021402_subsistence_amend.html; ALASKA SUBSISTENCE: A NATIONAL PARK SERVICE MANAGEMENT HISTORY, at p. 247 (Sept. 2002), available at https://www.nps.gov/subjects/alaskasubsistence/upload/Norris_For_Web.pdf.

23 For example, to engage in subsistence hunting in a national park in Alaska, one must meet Federal Subsistence Board regulatory requirements regarding eligibility. 50 C.F.R. § 100.5 (pertaining to rural residency and customary and traditional use determinations). The hunter must also meet NPS specific eligibility requirements which are found in 36 CFR Part 13, which states “[s]ubsistence uses by local rural residents are allowed pursuant to the regulations of this subpart ….” 36 C.F.R. § 13.410 (emphasis added). NPS regulations define “local rural resident” for national parks and monuments as a person who resides in the park or monument “resident zone” (also a defined term) or has a permit from the park superintendent. 36 C.F.R. §§ 13.410, 13.420. The “resident zone” is specific to the national park or monument. See, e.g., 36 C.F.R. § 13.1902(a). Also, the hunter must possess an Alaska hunting license and “any pertinent permits, harvest tickets, or tags required by the State[.]” 50 C.F.R. § 100.6(a)(1), (3). The hunter must also determine whether any NPS rules further restrict harvest practices within the NPS unit. See, e.g., 36 C.F.R. § 13.480 (hunting closures and restrictions) and 13.450 (restrictions on using an airplane to access parks and monuments for subsistence hunting and fishing).

24 NPS attempted to resolve some of the confusion in rulemaking adopted in 2020 which stated harvest for “sport” means any harvest outside ANILCA’s rural subsistence provisions, including general (or recreational) hunting and state authorized subsistence. Alaska; Hunting and Trapping in National Preserves, 85 Fed. Reg. 35181, 35185 (June 9, 2020).

25 For example, the State authorized harvest of black bear cubs and sows with cubs at den sites with articifical light. 5 AAC 92.260(1), 5 AAC 92.080(7)(C). NPS objected to allowing the practice under ANILCA’s authorization for “sport” harvest and adopted rules prohibiting it in national preserves in Alaska. The State responded “[w]e further disagree that this limited, customary and traditional subsistence practice creates an unacceptable impact to preserve values….”). State of Alaska ANILCA Implementation Program, Comments on Proposed Changes to 2010 NPS Compendiums at p. 3 (Feb. 15, 2012).

26 ALASKA STAT. §16.05.255(k).

27 See, e.g., ALASKA STAT. §16.05.255(e); State of Alaska Department of Fish and Game Emergency Order on Hunting and Trapping 04-01-11 (Mar. 31, 2011) (on file with authors) (also available at Administrative Record for Alaska v. Jewell et al., No. 3:17-cv-00013-JWS, D. Alaska pp. NPS0164632-35), State of Alaska Department of Fish and Game Agenda Change 11 Request to State Board of Game to increase brown bear harvest in game management unit 22 (2015) (on file with authors) (also available at Administrative Record for Alaska v. Jewell et al., No. 3:17-cv-00013-JWS, D. Alaska pp. NPS0003786-88; Alaska Department of Fish and Game Wildlife Conservation Director Corey Rossi, “Abundance Based Fish, Game Management Can Benefit All,” ANCHORAGE DAILY NEWS (Feb. 21, 2009) (on file with authors) (also available at Administrative Record for Alaska v. Jewell et al., No. 3:17-cv-00013-JWS, D. Alaska pp. NPS0121421-24); ADFG News Release—Wolf Hunting and Trapping Season extended in Unit 9 and 10 in response to caribou population declines (3/31/2011) (on file with authors) (also available at Administrative Record for Alaska v. Jewell et al., No. 3:17-cv-00013-JWS, D. Alaska pp. NPS0164703-04); Alaska Department of Fish and Game Craig Fleener, Testimony to US Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources re: Abundance Based Wildlife Management (Sept. 23, 2013) (on file with authors) (also available at Administrative Record for Alaska v. Jewell et al., No. 3:17-cv-00013-JWS, D. Alaska pp. NPS0144687-96), Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Hunting and Trapping Emergency Order 4-01-11 to Extend Wolf Hunting and Trapping Seasons in GMU [Game Management Unit] 9 and 10 (LACL and KATM) (Nov. 25, 2014) (on file with authors) (also available at Administrative Record for Alaska v. Jewell et al., No. 3:17-cv-00013-JWS, D. Alaska pp. NPS0164699-702); ADFG Presentation Intensive Management of Wolves, Bears, and Ungulates in Alaska (Feb. 2009) (on file with authors) (also available at Administrative Record for Alaska v. Jewell et al., No. 3:17-cv-00013-JWS, D. Alaska pp. NPS0004375-90).

28 NPS Management Policies, §§ 4.1 and 4.4.1 (2006), available at https://www.nps.gov/policy/MP_2006.pdf.

29 ALASKA STAT. §16.05.255(k).

30 Between 2005-2015, NPS objected more than 50 times to proposals to liberalize predator harvest practices (e.g., trapping bears, using snowmachines to take or pursue wolves, baiting brown bears) in areas that included preserves. Administrative Record for Alaska v. Jewell et al., No. 3:17-cv-00013-JWS, D. Alaska pp. NPS0143855-60). See also NPS proposal to the Board of Game to exclude preserves from state regulation allowing harvest of black bear cubs and sows with cubs at den sites with articifial light (2010), Agenda Change Request to Alaska Board of Game from NPS to exclude preserves from predator harvest provisions restricted by NPS (11/6/2013). It is also worth noting NPS adopts state hunting regulations in the absence of a conflict with federal law or regulations. 36 C.F.R. §§ 2.2(b)(4), 13.42(a). Preemption of state hunting rules has occurred only in limited circumstances. See, e.g., 36 C.F.R. § 13.42(d) (prohibiting same day airborne harvest of most big game species in Alaska).

31 See ALASKA CONST., art. VIII, § 4; ALASKA STAT. 16.05.020(2); Board of Game Transcript for Statement of Chairman Judkins (Feb. 27, 2010) (on file with authors) (also available at Administrative Record for Alaska v. Jewell et al., No. 3:17-cv-00013-JWS, D. Alaska pp. NPS0012673, 82-83); State of Alaska ANILCA Implementation Program, Comments on Proposed Changes to 2010 NPS Compendiums at p. 5 (Feb. 16, 2010) (“ADF&G is responsible for the sustainability of fish and wildlife in the State of Alaska, regardless of land ownership, and is the primary management authority for fish and wildlife, which includes determining healthy populations and allocating fish and wildlife—including for subsistence purposes—unless specifically preempted by federal law.”) (on file with authors) (also available at Administrative Record for Alaska v. Jewell et al., No. 3:17-cv-00013-JWS, D. Alaska pp. NPS0168520, 24); State of Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Comments on Proposed Changes to 2013 NPS Compendiums at p. 3 (Feb. 14, 2013) (“given the State’s responsibility to provide for the sustainability of all wildlife within iits borders—regardless of land ownership or designation. . . .”) (on file with authors) (also available at Administrative Record for Alaska v. Jewell et al., No. 3:17-cv-00013-JWS, D. Alaska pp. NPS0093987, 89).

32 ANILCA § 1313, codified at 16 U.S.C. § 3201.

33 Bear baiting is also prohibited in Chugach and Denali State Parks presumably to avoid safety concerns and user conflicts rather than biological concerns about the bear population. See 5 AAC 92.044(b)(1); www.adfg.alaska.gov/static/regulations/wildliferegulations/pdfs/2020_2021_bear_baiting_seasons_and_requirements.pdf (last visited Jan. 3, 2022); State of Alaska Department of Fish and Game, 2020-2021 Alaska Hunting Regulations, at p. 27 (“Bait MAY NOT be used and bait stations MAY NOT be registered in the following areas:…Units 13E and 16A in Denali State Park.”).

34 See, e.g., State of Alaska ANILCA Implementation Program, Comments on Proposed Changes to 2012 NPS Compendiums at p. 3 (Feb. 15, 2012) (“The State asserts the proposed closures [to wolf and coyote harvest] at 13.40(e) for Aniakchak, Katmai, and Lake Clark National Preserves are unwarranted as no biological reason has been provided as justification.”); State of Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Comments on Proposed Changes to 2013 NPS Compendiums at p. 3 (Feb. 14, 2013) (“Service action implies a formal finding (but without corroborating evidence) that state management fails to ensure the conservation of species and sustained yield management principles. And given the State’s responsibility to provide for the sustainability of all wildlife within its borders—regardless of land ownership or designation—and its authority, jurisdiction, and responsibility to manage, control, and regulate wildlife populations, including for subsistence purposes, unless specifically preempted by federal law, we are disappointed in the recent approach the Service has taken to preempt state harvest regulations.”); State of Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Comments on Proposed Rule RIN 1024-AE21 (Nov. 26, 2014). The State of Alaska and two hunting organizations sued the Department of the Interior over the 2015 rule, arguing that the rule was inconsistent with ANILCA. Complaint for State of Alaska v. Jewell, No. 3:17-cv-00013-JWS (D. Alaska), Complaint for Safari Club International, Inc. v. Jewell, No. 3:17-cv-00014 (D. Alaska), Complaint for Alaska Prof. Hunters Assoc. v. Jewell, 3:17-cv-00026-HRH (D. Alaska). These lawsuits were later dismissed after a new administration rescinded the 2015 rule. State of Alaska v. Haaland et al., No. 3:17-cv-00013-SLG (June 24, 2021).

35 Repanshek, K., Conservation Groups File Lawsuit To Protect Predators On Park Lands, NATIONAL PARKS TRAVELER, (Aug. 26, 2020), https://www.nationalparkstraveler.org/2020/08/conservation-groups-file-lawsuit-protect-predators-park-lands.

36 ANILCA § 811, codified at 16 U.S.C. § 3121.

37 See, e.g., General Management Plans adopted between 1985-1986 for Cape Krusenstern, Denali, Gates of the Arctic, Kobuk Valley, Noatak, and Yukon-Charley Rivers. But see, General Management Plan for Wrangell-St. Elias (1986).

38 See, e.g., National Park System Units in Alaska, 73 Fed. Reg. 67,390 (Nov. 14, 2008).

39 See, e.g., National Park Service, Nabesna Off-Road Vehicle Management Plan, Final Environmental Impact Statement (Aug. 2011); Ahlstrand, G. M., Racine, C. H. Response of an Alaska, U.S.A., Shrub-Tussock Community to Selected All-Terrain Vehicle Use. 25 ARCTIC AND ALPINE RESEARCH 142 (1993).

40 ANILCA § 1110(a), codified at 16 U.S.C. § 3170(a).

41 National Park System Units in Alaska; Denali National Park and Preserve, Special Regulations, 65 Fed. Reg. 37863, 37867 (June 19, 2000).

42 Only one NPS unit has adopted a definition of “traditional activity” through rulemaking. This regulatory definition, which relies on the consumptive use examples cited in legislative history, is quite narrow, and applies only to the former Mount McKinley National Park (an area mostly designated as wilderness). The on-the-ground effect of this definition is that snowmachines are not authorized in this area. 36 C.F.R. §§ 13.950-13.962; see also National Park System Units in Alaska; Denali National Park and Preserve, Fed. Reg. 65 FR 37863.

43 See 43 C.F.R. § 36.11(e). The qualifying language was also eliminated for motorboats and airplanes. See 43 C.F.R. 36.11(d), (f). An explanation for the expanded authorization is found in the Federal Register related to the rule. Transportation and Utility Systems in and Across, and Access Into, Conservation System Units in Alaska, 51 Fed. Reg. 31619, 31626 (Sept. 4, 1986).

44 A 1976 statute provides NPS authority over activities “on or relating to waters” within NPS units, regardless of ownership of submerged lands. In 1996, NPS clarified its regulations to remove ambiguity on this point. General Regulations for Areas Administered by the National Park Service and National Park System Units in Alaska, 61 Fed. Reg. 35,133 (July 5, 1996).

45 Codified at 16 U.S.C. § 3103(c).

46 36 C.F.R. § 1.2(a)(3) (1996). See Brief for the United States, Sturgeon v. Frost II, No. 17-949 at 12 (Sept. 2018). See also, Solid Waste Sites in Units of the National Park System, 59 Fed. Reg. 65,948 (Dec. 22, 1994), General Regulations for Areas Administered by the National Park Service and National Park System Units in Alaska, 61 Fed. Reg. 35,133.

47 ANILCA references the term “water” 151 times, “river” 180 times, “stream” 21 times, and “lake” 59 times. Many of the NPS units established by ANILCA are named for waterbodies within those units (i.e., Aniakchak, Lake Clark, Yukon-Charley Rivers, Noatak).

48 Authority to restrict boating is found in sections 811(b) and 1110(a), codified at 16 U.S.C. §§ 3121(b), 3170(a) respectively. Authority to restrict fishing is found in section 1313 (codified at 16 U.S.C. § 3201).

49 36 C.F.R. § 2.17(e).

50 Alaska Statehood Act, § 6(m), 72 Stat. 343, incorporating the Submerged Lands Act (43 U.S.C. 1301 et seq.).

51 “The Service’s rules will apply exclusively to public lands (meaning federally owned lands and waters) within system units. The rules cannot apply to any non-federal properties, even if a map would show they are within such a unit’s boundaries. Geographic inholdings thus become regulatory outholdings, impervious to the Service’s ordinary authority.” Sturgeon II, 139 S.Ct. at 1082.

52 Hunting is prohibited in national parks unless specifically authorized by statute. 36 C.F.R. § 2.2(b). Within national parks in Alaska, only subsistence by rural residents is allowed (see, e.g., enabling authorization for Gates of the Arctic and Wrangell-St. Elias National Parks in ANILCA sec. 201). Wasilla is not considered “rural” under Federal subsistence rules. 50 C.F.R. § 100.23.

53 Mining and ground disturbance is prohibited under 36 C.F.R. §§ 2.1(a)(1)(iv), 5.14.

54 Fishing is limited to use of “hook and line” under 36 C.F.R. § 2.3(d)(1) except by federally qualified rural subsistence users in accordance with 36 C.F.R. § 13.470.

55 As a national park, only subsistence hunting by rural residents is authorized.

56 Use of all-terrain vehicles (also called off-road vehicles or ORVs) is generally not allowed in NPS units. See 36 C.F.R. § 4.10(a).

57 “Taking” wildlife is prohibited in national park system units unless authorized by statute. 36 C.F.R. § 2.2(a). ANILCA authorizes taking of wildlife for sport purposes and for subsistence. See supra note 52, ANILCA § 1313 codified at 16 U.S.C. § 3201.

58 Jurisdiction in Alaska, 85 Fed. Reg. 72956, 72958 (discussing the meaning of “ordinary regulatory authority”).

59 State of Alaska Navigable Waters Map at https://mapper.dnr.alaska.gov/map#map=4/-16632245.12/8816587.34/0 (last visited Aug. 7, 2021).

60 State Policy on Navigability, at https://dnr.alaska.gov/mlw/paad/nav/policy/ (last visited Aug. 7, 2021)

61 The Daniel Ball, 77 U.S. 557 (1870).

62 PPL Montana, Inc. v. Montana, 565 U.S. 576 (2012).

63 State Policy on Navigability, at https://dnr.alaska.gov/mlw/paad/nav/policy/ (last visited Aug. 7, 2021).

64 Federal ownership of submerged lands in the pre-Statehood portion of Glacier Bay was confirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2005. Alaska v. United States, 100 U.S. 1 (2005). Other waterbodies (or portions thereof) within NPS units subject to a federal navigability/ownership determination—all confirming ownership to the State—include the Alagnak River (Alagnak Wild River and Katmai), Muddy River (Denali), Kantishna River (Denali), Kukaklek Lake (Katmai), Nonvianek Lake (Katmai), Nonvianek River (Katmai), Kandik River (Yukon-Charley Rivers), Nation River (Yukon-Charley Rivers).

65 The State of Alaska also makes assertions of navigability. See State Policy on Navigability, at https://dnr.alaska.gov/mlw/paad/nav/policy/ (last visited Aug. 7, 2021); State of Alaska Navigable Waters Map at https://mapper.dnr.alaska.gov/map#map=4/-16632245.12/8816587.34/0 (last visited Aug. 7, 2021).

66 Alaska Department of Natural Resources, Unlocking Alaska Initiative, at https://gov.alaska.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/Unlocking-Alaska-Initiative.pdf (last visited Aug. 7, 2021).

67 For example, the “Special Access” allowance in ANILCA authorizes land managers to adopt “reasonable regulations” and even prohibit access authorized under that section if such use “would be detrimental to the resource values of the unit or area.” ANILCA § 1110(a), codified at 16 U.S.C. § 3170(a). However, due to political pushback, restrictions or closures are often not feasible for NPS managers. But see, “Byers Lake [in Denali State Park] is closed to boats with gasoline operated motors and aircraft to insure the tranquility of the area.” http://www.dnr.alaska.gov/parks/aspunits/matsu/byerslkcamp.htm (last visited Aug. 5, 2021).

68 For example, in the northern part of Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve, areas where off-road vehicles have become an established use resulted in acreage being removed from wilderness eligibility. Regional Director, NPS Alaska Region Memorandum to NPS Director regarding Wrangell-St. Elias Wilderness Eligibility Reclassification, Nabesna Off-Road Vehicle Final Environmental Impact Statement (Dec. 19, 2011).

69 NPS restricted snowmachine use in the former Mt. McKinley National Park. 36 C.F.R. § 13.952.

70 Letter from Mike Dunleavy, Alaska Governor (received Dec. 1, 2021) (Dunleavy for Governor campaign donation solicitation).

71 See General Management Plans adopted between 1985-1986 for Cape Krusenstern, Denali, Gates of the Arctic, Kobuk Valley, Noatak, Wrangell-St. Elias, and Yukon-Charley Rivers.

72 See, e.g., Public Law 115-20, 131 Stat. 86 (Apr. 3, 2017).

Last updated: June 23, 2022