Part of a series of articles titled What Daddy and Mother did in the War.

Article

What Daddy and Mother did in the War (Part 4)

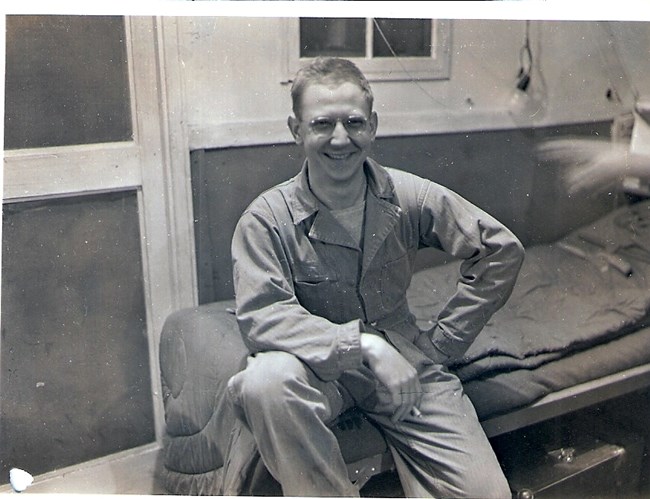

Bob Johnson, courtesy of his daughter Stephanie Dixon

I'll be Seeing You: Furloughs

In The Williwaw War, Goldstein mentions that late in 1942 the Aleutians troops began to be given furloughs back to the States. This first was done through a lottery system and men started going on 15-day furloughs through rotation.

Dr. Bob Boon recalled the story: "In May 1943 we were given a chance to come home on furlough as part of that process. But we had to find our own transport. We were to go down to the dock and wait for a chance to catch a ride.” Boon also reported that he and Bob Johnson were in a group that were allowed 30-day furloughs.

“One day at the dock, this dilapidated tug came through pulling a barge of scrap. The tug was short two men on crew and said we could ride to the states. It turned out that in a storm the front hatches been damaged and so the available bunks leaked water. So I went down by the engine room to try to sleep, and slept on a coil of rope down there. It was an old WWI hand-fired tug and quite dusty. By the time we got to states I was quite dirty, since no there were no facilities to wash and no toilets. You had to hang onto a rope and hang over the side.”

Bobby Boon may have been dirty but Bob Johnson was in even worse shape. Boon continued, “Bob became very seasick and when the tug finally got to Prince Rupert in Canada, he was taken off the tug and taken to the hospital to be rehydrated from prolonged vomiting. There was no option for me to stay with him. I got put on a freight/ passenger boat to Vancouver, and then on a train to Ft. Lewis where I finally could get cleaned up. I was given clothes, then went on by train to Minnesota and then down to Arkansas, where furlough started.”

“We got 30 days," Boon said. “After Bob recovered, he came on to the States. All this time didn’t count against furlough till we got to Ft. Lewis.”

While on furlough in Arkansas the two Marianna boys went around and visited many friends and family. They went to see a buddy from Jonesboro, who threw them a party. Some photographs exist showing the two Bobs at this party, in their dress uniforms, with new and old friends.(Boon)

GI Jive: Back to Dutch Harbor, on to Amchitka

After their furlough, in l943 the regiment was broken up and sent back to the States for retraining as a combat unit. Boon said “The band was given the opportunity to transfer into a gun battery.” Those who chose that option would be reactivated, most of them to a lower rank, and send on to Europe to fight with the infantry or they could stay in the band and go to Amchitka. Boon says that he and Bob Johnson put their heads together and decided they’d rather stay in the band. They were on Amchitka for a year. (Boon)

As hard as it was to believe, many men chose the option to go to the European theater. Going to the thick of the fighting in Europe was preferable to those bored, lonely, depressed soldiers than staying another night in the Aleutians. The ones who chose to stay, figuring that they probably would be safer where they were, (Boon), were designated as part of the 238th Army Ground Forces Band.

"Bob and I elected to stay there and shortly after we were sent to Amchitka. Then replacements were sent up from the States. All of them were draftees,” Boon explains. These replacements also filled slots of the band members who chose to go to Europe. By the time the war ended Bob Johnson and Bobby Boon were the only two original members of the 206th Band still in the Aleutians. (Boon)

“By the time the war was over, the band company replaced everyone but he and I,” Dr. Boon asserts.

Before they left Dutch Harbor, the remains of the old 206th Coast Artillery, now designated the 238th Ground Forces, loaded all their equipment on a barge. Dr. Boon remembered that the barge meandered out to Amchitka, which was quite a long way. “When we got there we played for some parades and Officers Clubs and some USO entertainers.”

On Amchitka the military consisted of a 28-piece band, with the rest being part Navy , part Army, and part Air Corps, which built an air strip that was used to fly reconnaissance. There were nurses, who dated only officers, and some civilians that Dr. Boon says they had little or no contact with.

Bob Johnson, courtesy of his daughter Stephanie Dixon

It was pretty much business as usual with eternal days or nights, depending on the season. Boredom was again the enemy. Depression and suicide became the result. It was the band’s job to keep up morale, but it was a losing proposition. It became so bad that even the top USO entertainers couldn’t break the gloom. Goldstein reports that Bob Hope and singer Frances Langford came to some of the islands, but got a ho-hum reception. In 1943 when singer Martha O’Driscoll, apparently a favorite of the time, came to Amchitka for a performance, many of the soldiers couldn’t even be bothered to get out of their bunks and go watch. This was a very bad sign. (Goldstein and Dillon)

Goldstein points out that most of the men were in tough shape. Then he quotes from a book by Brian Garfield, The Thousand-Mile War: World War II in Alaska and the Aleutians: "A few psychology logically hardy souls took up such hobbies as photography, but they were in the minority. All too many 'turned inward to feed on their own acids, and retired from reality.'"

So that’s where he learned photography! As gratifying as it is to see one’s father described as a “psychologically hardy soul” sixty-four years after the fact, these conditions could not have been good for the mental health of any of the men.

By all accounts, the Southern boys from rural areas fared much better than those from the North. Plus, Dr. Boon does not think that they lost any band members to suicide. Although there is no conclusive proof about the why or wherefore, it seems logical to suggest that perhaps the Southerners, the farm boys, were accustomed to wide open spaces and to having to entertain themselves. Don’t suggest to them that there was nothing to do or to think about as long as there were fish all around them and wildlife to shoot at. Besides, being hard-wired to keep busy had to have helped. The Southerners, with their close family connections and boyhood friends in their own unit were much better equipped to withstand the harsh, lonely stretches of the Arctic winters.

At some point in his Aleutian service, Bob Johnson was awarded a Purple Heart, (Johnson), although none of his survivors knows where it is, if indeed it ever got to him. He said that it came about due to the arrogance and stupidity of “another 90-day Wonder.” He claimed that a group of men from his unit, with Dad as sergeant, were ordered by a lieutenant brand new to the Aleutians to put on light packs for a hike into the mountains. When Bob called out his group and they all were standing in winter uniforms with heavy packs, the lieutenant blew a gasket. Despite Bob’s reasoning and pleading that the men knew what they were marching into and wouldn’t volunteer to carry the heavy packs and clothes unless they were really needed, the new officer was hell-bent to show his authority. He ordered then to change their clothes and bring the lighter packs.

Of course, when they left the sun was out. Within a few hours the men had marched up into the hills and bad weather came in. They were trapped and nearly frozen when a search party was sent after them. Dad said, “Most of us had to be carried out of there on stretchers. I was one of them, and so was that officer!” Dad suffered frost-bitten feet and had trouble with them the rest of his life. For his part, the officer was given an immediate transfer out of there for his own safety, and we hope, was busted to buck private.

On Amchitka, Dr. Boon reports that both he and Dad found themselves doing more extra work away from their band duties. There were regular stands at watch. “ We had to pull some guard duty for the balloons that the Japanese were sending over to try to set fire to the woods in Washington. One of them fell or was shot down on Amchitka. It was kept under lock and key.”

US Navy, Library of Congress, LC-USW33-032363-ZC

Don't Be That Way: The Battle of Attu

There were bloody battles and battles of nerves on the islands of Kiska, Adak, Kodiak, and especially Attu that continued as the war dragged on. “We were bombed and strafed in Dutch Harbor for two days. When that attack failed, the Japanese went to Attu. They stayed there till Roosevelt’s next election for president,” Boon remembered. That would have been Roosevelt’s fourth and final term. The Attu occupation by the Japanese, though not an immediate threat, was embarrassing to the Roosevelt administration and became a campaign issue. It was critical to that election that the Japanese be driven off of American soil. So they were, although it was costly.

Though our father and his compatriots were no part of it, an amphibious landing commenced against the Japanese on Attu on May 11, l943. Although the Navy was charged with getting the fighting force there, most of the fighting was done by Army and Marine assault troops. Many of men charged with taking the island were new recruits from the California bases. They were sent to the Aleutians in warm weather gear, wholly unsuited to the climate they had to fight in. A good many men suffered from frostbite from slogging through the water and the muskeg; gangrene set in and many had to have toes amputated. (USN Combat Narrative)

It took the better part of the month to secure the island for the Americans and to rout the Japanese, who nearly fought to the last man. The final count was 2351 Japanese killed and only 28 prisoners, with no officers taken. The U.S. forces assumed that more were killed and already buried by the time they got there and accounted for the dead. (USN Combat Narrative)

It was no picnic for the Americans, which reported 3829 casualties: 549 killed, 1148 injured, 1200 with cold injuries, 614 sick, and the others with miscellaneous injuries. That was 25% of the U.S. fighting force on the island.

There were several frightening naval engagements between the U. S. and Japan among the Aleutian Islands. Our father did not take part as a combatant in any of those engagements. But Japanese submarines patrolled the Aleutians throughout the war, menacing anyone and everyone who inhabited the island chain.

All reports of submarine, ship, or plane sightings were taken seriously. One such report, which woke everyone up, turned out to be a false alarm, according to Dr. Boon.

After the Japanese had taken Attu and were well established, the word came down that they were sending landing parties to make raids. They came on subs, landed in rubber boats, shot things up and left. Also the sub might come in the harbor and use its deck guns to shell the harbor. The Navy then installed a sub net across the harbor.

Shortly thereafter at about 2:00 a.m. there was a general alarm that a sub had set off the alarm on the sub net. All hands charged out to man the guns and the Navy raced out to drop depth charges.

About daylight a dead whale floated up, still caught in the sub net, and proceeded to create a pervasive stench for at least ten days---but no sign of Japs or subs. (Boon letter)

Bob Johnson, courtesy of his daughter Stephanie Dixon

Take the "A" Train: Going Home

Then in early May l945, with the War in Europe over and the War in the Pacific grinding down, it was announced that soldiers who had accumulated 120 combat points could go back to the States and be discharged. (Boon, Goldstein and Dillon)

“So we elected to do that,” Dr. Boon reported. I can only imagine how my father felt that day knowing that he soon would be home again in Arkansas, a place he left after that only under duress.

For Dr. Boon’s part, he must have been very excited, because although he has total recall of nearly every other event concerning him and our father, he does not remember if they traveled together back to the States or how Bob Johnson might have gotten there. He knows that they both had enough points to leave., and believes that they started back in about May of 45.

Boon said, “Again we had to hitch rides and had to find our own transport. I got a plane to Adak. I went there and pulled my first day of KP. I was only a Buck Sergeant and was out-ranked by everybody. Then I got a freight plane to Anchorage and another to Edmonton, Canada. I believe that we traveled together until we arrived at Edmonton. Then it was every man for himself. I stayed there and waited for orders to continue. That’s when I took the train to Minnesota and another to Ft. Smith where I was discharged. I rode the bus home.”

As for his reception on returning home, Dr. Boon says simply, “My father and mother were happy to see me.”

Although we don’t know for sure what route Bob Johnson’s took on his final return from the Aleutians, it’s a pretty safe bet that it followed Bobby Boon’s closely. He certainly would have tried to catch a plane to avoid those ships and the sea-sickness that plagued him. And we do have that slip of paper from Wald-Chamberlain Field in Minneapolis, Minnesota dated July 3, stating that a train seat was reserved for him. It also routed him through Ft. Smith before he was given a bus ticket home as a free man.

He had gone into the service a boy. He came out a man, in every way imaginable. He was seasoned, he was a little taller and had added a couple of pounds. He had lost some of his black, curly hair (He believed it was because he never took off his cap the whole time he was there because his head was cold). He had shouldered responsibility, some of it heavy. His face was weathered. Most of all, he had experienced combat. It all showed in his face and body language in the yellowing photographs.

During his war years, Bob Johnson was careful with his money. He sent his monthly allotment, $15 at first, back to his parents for safe-keeping. They put it in the bank. Bob told his father, Floyd, that he wanted Floyd to be on the lookout for a business opportunity for the two of them. Floyd wrote him about a store that was available. Mr. Hoyle was selling his store in town. Would Bob be interested in going into business with his dad in a grocery store/meat market? Why yes, he believed he would. (Johnson)

Floyd Johnson made the deal after he talked with Mr. Hoyle and Hoyle told him, “Mr. Johnson, I guarantee you that by the end of the year, you’ll be making twice what you’re making now.” Floyd thought that sounded good enough to support him, Beadie, and Bob. We know that the store was purchased before Bob’s letter dated July ‘44, because he mentions coming home to work in it.

Bob Johnson was not the only soldier who did not blow his small check on poker games and beer. Sgt. Bob Boon also saved his $15 monthly allotment. His intention was to go back to college and get his degree. He was able to do that with the $1800 that he put in Col. Robertson’s bank back home.

After taking his degree in chemistry and abandoning an attempt to farm with his father, Bob Boon returned to the University of Arkansas to become a pre-med major. There he met his wife, Eloise. They married and decided that he would apply to medical school. Eloise supported them as a public school teacher until he completed the University of Arkansas Medical School on the GI Bill and was able to set up a practice, settling in Huntsville, Alabama. Dr. Boon kept his toe in military waters until he retired as a captain in the Air Force Reserves in January l957. He enjoyed flying and had his own place for many years.

It's Been a Long, Long Time: Back Home

Readjustment to civilian can be very difficult, even if one hates being in the military. “When you’ve been having someone tell you what to do every day, you suddenly realize “My God, I’ve got to do this on my own!” Dr. Boon stated.

We don’t know how hard it was for our father to readjust. When Bob got home he told Beadie and Floyd that he figured he’d need at least six weeks to get his civilian legs back under him. (Johnson) “I just need to hunt and fish for a while,” he told them. Bob told Stephanie that his parents agreed to give him the time to readjust. These days that would be called time to decompress.

Bob laughed when he said, “I hunted and fished all I could stand for two weeks, then I went to Dad and told him to give me something to do. I’ve been working ever since.”

His musical training and experience didn’t go to waste either. His mother, Beadie, and her sister, Sue Oxner, put their heads and considerable organizational talents together and decided that Marianna High School needed a band. And that is what happened. Beadie and Sue also convinced the powers that be that Bob was needed as its first director. In addition to his store duties, he directed the band on a voluntary basis for about a year until a permanent director could be found.

As handsome and personable a man as he was, it is not hard to imagine him attracting female attention when he returned home. Men had been in short supply for several years. When they began coming home, the Great Pairing-Off began. Courtships were short. People got married in record numbers. The Baby Boom began.

Our father was no different. The story of his and our mother’s brief courtship follows our mother’s story. The men who fought in that war obviously learned many life lessons during their service. Bob Johnson took many of those lessons to heart and passed as many as he could down to his children and grandchildren. But never did we hear the message that Dr. Boon claims was the one thing he learned from his military service, “Never volunteer for anything.”

This is Part 4 of "What Daddy and Mother did in the War." Read Part 5 next.

Last updated: July 18, 2025