Part of a series of articles titled What Daddy and Mother did in the War.

Article

What Daddy and Mother did in the War (Part 3)

Bob Johnson, courtesy of his daughter Stephanie Dixon

Stomping at the Savoy: Food and Living Conditions

It would have been a prime recipe for homesickness, if there had been time for it. But the men had to dig in and stay on alert. Official and unofficial reports indicated that the Japanese would be attacking U. S. territories soon. The fox holes were dug mostly in the mountains. The food was standard army fare, “warm and greasy.”(Boon)

The men soon learned that between williwaws it might be sunny with relatively pleasant days. But during active storms, it was impossible to walk. A person might be leaning nearly parallel to the ground, then fall flat on his face when the wind suddenly stopped. (Boon) They could count on such winds from early December until late May.

Some of the men discovered Blackie’s Bar, which was an infamous joint already in place at the town of Dutch Harbor before the war started. Blackie Floyd, the owner, was the reputed brother or half-brother of the gangster Pretty Boy Floyd. (Beauchamp, Goldstein and Dillon) He ran his establishment with an iron hand. Customers stood in line (which started outside) snaked in until it was their turn, paid their money for a drink, and then left out the back door. Drinks were $3 to $4 a beer, but the men often ran from the back door right back to a spot in line. (Goldstein and Dillon)

“We were very isolated, so we didn’t get much variety in our diet. A supply ship came every so often and some would go help unload the boats to steal some of the officers’ meat,” Boon alleges. “Fishing crews would go out to catch fish and would share with the others, because the army cooks would boil ribs and slap them on your mess kit, and a big blue stamp saying ‘USDA Inspected’ would still be on it. We got some canned vegetables and fruit but that was it.” And it was rare.

In the middle of the war when supply boats were coming in more slowly, the men survived on two meals a day of pancakes and sauerkraut. On Thanksgiving Day 1943 they only had sauerkraut, for breakfast and dinner. However, when the supply ship did arrive, everyone got a belated Thanksgiving dinner with all the trimmings. (Goldstein)

For toilet facilities, when they first arrived they had to use slit trenches. These are extremely primitive, basically out in the open. Later, outhouses were dug. The band had one designated as its own.

During the early years boredom was already leading to despair and a fair number of suicides, but none from the band. The band fought off those feelings with other activities. They accompanied many of the USO entertainers and celebrities who came to the Aleutians to cheer up the troops. The favorite of them all, by far, was comedian Joe E. Brown. (Goldstein and Dillon, Johnson) Brown not only entertained, he went around to all of the barracks and huts, visiting with the men for several days.

Through the war years, there were several entertainers and shows. Bob Hope and his show, ventriloquist Edgar Bergen and his monocled dummy Charlie McCarthy, Errol Flynn (who went over well with the nurses, but not necessarily the men), Olivia de Havilland (Melanie, Gone With the Wind), actress Marjorie Reynolds, and lesser lights.

Bob Boon claims that the band backed up most of these acts “since the Army wouldn’t spring for them to bring their own bands.” Dad proclaimed Edgar Bergen the most talented entertainer he ever saw. Most of the rest of the entertainers came with a small entourage, but Bergen showed up with only a trunk full of dummies. (Johnson)

Dad did not write many letters, at least few that survived. But there is one that he wrote to his family in July 1944. In it he specifically addresses his nephew, Mickey Odom, and tells him how much he wished Mickey could come up to Alaska and help him hunt foxes. “I’m scared of them, by myself,” he wrote. (Johnson letter)

Dr. Boon reported that the troops had fairly reliable mail service both to and from the States. He pointed out that some of the Dad’s old photographs of Dutch Harbor had a hole punched in the corner. This was the designation that the picture passed the censor.

With bad weather and sparse accommodations, there were ways to hurt yourself that no one had ever thought of. For example, fellow bandsman and Good Ole Marianna Boy, Cliff Williams, broke his arm in an odd nighttime accident. He got up in the middle of the night to go outside and relieve himself and slipped on the icy porch, falling and breaking his arm. The medical staff at the base hospital declared it a clean break and handed him a bucket full of coal. It didn’t need to be set, they said, but told Cliff he needed to keep it straight and strengthen it. The coal was the strengthening part of the equation. The trouble was that it was during cold weather and coal was in short supply. Cliff’s hut mates kept stealing his coal and burning it in the fireplace. (Beauchamp)

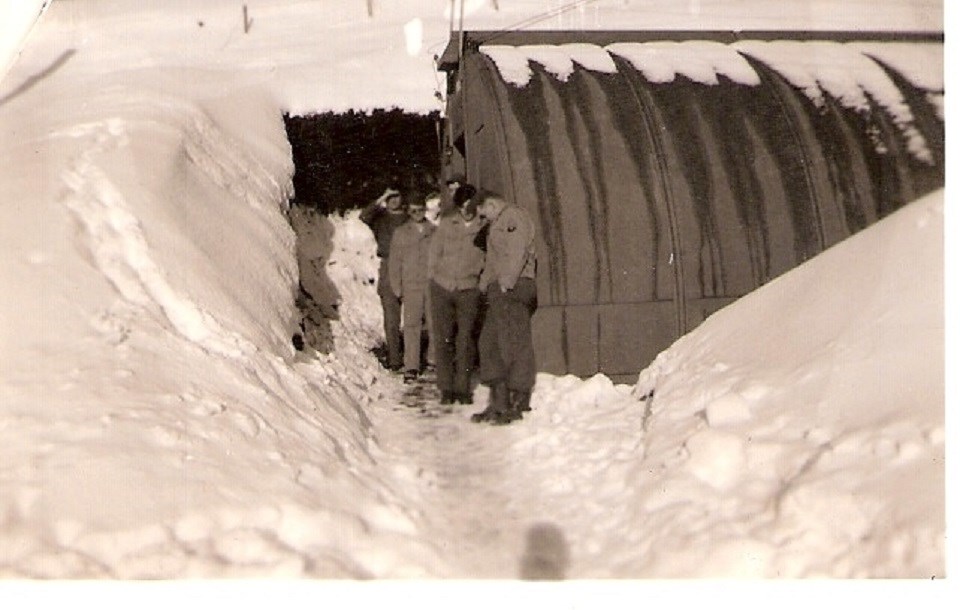

Dr. Boon states, “We had Sibley stoves, just conical pieces of metal with pipe. Most of the time it was fired with pressed sawdust. We’d also go to the dock and unload coal from the ships. You could take your bucket with you and fill it when you were there.

Boon continues that their Quonset huts were standard issue, which began to arrive in January of ‘42. Before that they lived in 8-man Army tents, which could be pretty uncomfortable.

But desperate times call for desperate measures. Boon also was the company supply sergeant and company clerk, and as such, had access to things that others might not. One could also say that he was the company moonshiner. “I got raisins or whatever kind of dried fruit I could scrounge from the mess sergeant and I’d make Sneaky Pete, a fermented beverage.” (Boon)

Some people also were able to take a large granite coffee pot and whittle a wooden insulator to fit in the spout and get a piece of copper pipe, That would strengthen the Sneaky Pete by partial distillation. (Boon)

Boon continues, “The rumor was that someone got a .30 caliber machine gun and used the water cooler from that to cool the steam,” but he never tried that, Boon claimed.

Bob Johnson, courtesy of Stephanie Dixon

Praise the Lord and Pass the Ammunition: The Japanese Attack Dutch Harbor

Bob Johnson didn’t enjoy talking with his children about his military experiences. But when he did respond to questions of being in combat during the war, he minced no words.

Stephanie remembers, "Daddy always told us that he was shot at only over a two-day period….that the Japanese sent airplanes in to attack Dutch Harbor and that the regiment expected them to come at some point, so the Americans were on alert. When someone saw the Japanese planes coming, everybody ran for the hills. They jumped in foxholes, which they previously dug into the side of the mountains and waited for them."

One of the scandals of the war in the Aleutians was the almost dismissive nature that the military hierarchy had toward the troops there, as if those men were expendable. Their equipment, although it did get better as the war went on, was not the most modern, effective, and there was not nearly enough of it. There was a dearth of ammunition, so much so that the commanders at Dutch Harbor put out orders to save what they had for “the real thing.” This would have been fine, if the men could have been adequately trained and thoroughly practiced with their weapons. But without ammo to practice with, mostly what the troops did with their artillery, small weapons, and rifles was to maintain it and learn to take it apart and put it back together in the dark. (Goldstein) For the men in the band, there was even less ammunition available, although when the Japanese attacked, the bandsmen were under attack also.

Dr. Robert Boon has a clear memory of what happened before and during the attack. “We had been put on alert many times and told we would be attacked. Our troops gradually had built up force by two regiments. They dispersed the gun batteries and moved out them of Ft. Mears into the hills and dug in. People in the band were to help as ammunition passers, and such. So we spent most of that time helping dig out for foxholes and gun emplacements.”

Dr. Boon recollected his experience. “We had been on alert for some time and told to be ready to “run for the hills”. We had several drills and some false alarms.” In confusion one night, Boon said the alarm was sounded and he jumped out of bed and put his galoshes on wrong feet, making a swift ascent into the mountains comical and impossible.

Boon also says that in their role as medical assistants the band members wore Red Cross armbands. They were not supposed to carry weapons and wear those armbands, as it was against the Geneva Convention accords. But with Japanese planes shooting at everyone, the band included, most of the men must have felt that this was too fine a distinction.

“Daddy told me once that he and several others slipped off their Red Cross armbands and put them in their pockets. They tried to defend themselves and their regiment when the Japanese planes came over. When they came back out of the hills after the battle, they put the armbands back on,” Stephanie states.

“When the real attack started we were alerted probably an hour before that something going on. Of course, we didn’t know it was a side-show to the Battle of Midway. Dutch Harbor was just a diversion, “Boon continued. “ Our radar crews were not really that familiar with the equipment. They saw some blips and the first actual attack was by high altitude bombers, followed by strafers on the main camp, which we had vacated.”

According to the authors of The Williwaw War, the attack on Dutch Harbor was expected by everyone there, even civilians. Warnings came as early as May of l942. And the warnings were grim. One report had it that 65,000 Japanese troops were on the way. Another predicted that the Americans would be outnumbered 6 to 1. Due to the fact that Americans had broken the Japanese code, the American troops knew they were coming under attack, they just weren’t certain when that would be. But one report on June 2 indicated that a Japanese carrier was spotted about 400 miles away from Unalaska Island.

Bob Johnson, courtesy of his daughter Stephanie Dixon

“We knew that the attack on Dutch Harbor would be a diversionary tactic. Our side had that information and ambushed the Japanese at Midway. The main body of their fleet was destroyed there,” Boon said. This was cold comfort for people sitting in foxholes with pistols, waiting for the Japanese Emperor’s Navy and Air Corps to come at them.

Col. Robertson and other commanders ordered both army and navy personnel to man the anti-aircraft guns at the beaches and other possible invasion sites. Some of the men slept in foxholes in the mountains, while others slept for days in their clothes with their rifles either laying across them or nearby. (Goldstein and Dillon)

When the attack came, it was still a surprise. The Japanese planes left the carriers Ryujo and Junyo at approximately 3:18 a.m. on June 3, 1942. The planes had delayed taking off due to heavy fog. This fog prevented the Junyo planes from locating Dutch Harbor and they returned to their ship, leaving only the 17 planes from the Ryujo to complete the attack. By 6 a.m. they were over Dutch Harbor, Unalaska and starting the fight. (Goldstein and Dillon, 144-145)

On the first pass, recon planes photographed the island with the fighters and bombers close behind. Despite the fact that some of the American troops began firing on the Japanese immediately, an odd “no fire” order went out from Col. Robertson. It was believed that the Japanese planes might be friendly Navy planes. When the Japanese began their second pass and started bombing, school was out. It was clear that they were under enemy attack and the Americans responded in kind. (Goldstein)

When the Japanese Zeroes came out of the clouds at Dutch Harbor, many of the men on the island were either at their posts or scrambling to them. The three-inch guns there for port protection were not set to angles that made it possible to hit any of the planes, which mostly flew at high altitudes. However, some of the anti-aircraft fire was effective at hitting some of the planes, it just wasn’t enough to bring down any.

The Japanese would dive down and attack, then pull up out of range from the American guns. Some of the American troops were still in bed when the attack started and initially thought that target practice was going on, but then remembered that nobody would waste that much ammo. They scrambled to safety. (Goldstein and Dillon)

Dr. Boon reported that his Bob Johnson’s hutmates got out and up into the hills in a hurry. “We were strafed, but all of us were in foxholes, so we were all right. Our antiaircraft crews were quite active.”

It did not take long for all military personnel on the island to get to their posts and start firing at the Japanese. Many of the 206th had to use steel helmets left over from WWI and went into their foxholes with only their sidearms to protect themselves. Had it been a full-scale assault, it is doubtful that the Americans could have defended themselves very well.

“During the Japanese attack, we were below the gun battlements and they shot over our heads. All the band was allowed to carry was pistols, so we used pistols to shoot at them,” Dr. Boon stated.

The men were in danger not only from direct hits by the bombs, but by the shrapnel hitting all around them. (Goldstein, 152) There was no air support for the Americans because the air corps located nearby was not close enough to get there until the fighting was over. Plus, communication to the outside world was not up to par. An ocean cable was not completed until July, a full month after the attack. (Goldstein and Dillon)

The high altitude bombing took its toll on the base hospital and on some of the Ft. Mears barracks area. Most of the casualties happened there. (Goldstein, 152) Once they got over Dutch Harbor, the weather cleared for the Japanese, giving them the definite advantage.

The tragedy of the casualties is that most of the men who died or were greatly injured were troops that had come in only the day before. They weren’t yet informed that they should hit the shelters at 4:30 a.m. Goldstein and Dillon state in The Williwaw War that bombs “struck Barracks 864 and 866, catching the new troops just as they were ‘leaving the barracks and into formation.” Seventeen were killed and 25 were wounded.

Bob Johnson was less charitable in his determination of what happened and he told the story with authority, as if he knew. He stated more than once that the unfortunate men in those barracks were ordered out into the street and to attention by a 90-day Wonder, an unflattering term for a brand new second lieutenant who had recently completed Officer’s Candidate School. These men were felt by the enlisted men to be impressed with their own sense of power and not possessed of much sense of any kind. In this case, the assessment was probably true. The officer himself was also killed, standing at attention in the middle of the street, as the Japanese dropped bombs upon him and his men.

Another set of casualties occurred when an officer in the Engineer company marched his troops into their foxholes just before a bomb hit in the middle of it. It appears that the targets on June 3 were the warehouses that presumably held ammunition. Two warehouses were destroyed. (Goldstein and Dillon)

“The base hospital was hit, along with some civilian targets. Some civilian workers and troops, about 170 or so were killed, but no one from our unit,” Dr. Boon believes. A nurse at the base hospital is credited with moving the 13 patients in the base hospital into the cement basement, thus saving them from further injury or death. (Goldstein and Dillon)

Bob Johnson, courtesy of his daughter Stephanie Dixon

One Zero was hit and crashed into the Bay. But the anti-aircraft guns were not of much use. They couldn’t be set at lower than 15 degrees, and the Zeros came in lower than that. Bob Johnson reported that the American boys had been told that the Japanese had poor eyesight, which made them less-than-great pilots and worse shots. Neither of these theories was true. “He told me that he saw the planes come out of the sky, turning sideways to get through the valleys without crashing into the mountains, and mostly avoiding the gunfire that came at them. He reported being close enough to them to see the pilots’ faces. These were images which clearly were etched in his memory,” Stephanie relates.

He wasn’t the only one. Ralph Beauchamp told his daughter, Sandy, many times of that attack. He thought that he may have shot down a Japanese plane. “I couldn’t have missed him,” Ralph said. “He looked right at me and smiled.” Ralph was convinced that his gunfire hit the plane. (Beauchamp)

The stories of these men and others of the 206th are all the more impressive when one understands that they defended themselves with inadequate weaponry that they were not even close to being adequately trained on. It was much like being sent out to go bear hunting with a switch.

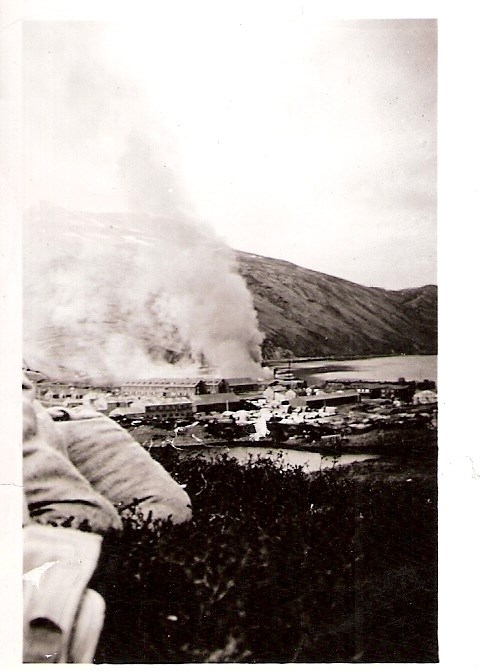

The black smoke seen in some of Bob Johnson’s pictures from the war evidently came from fuel tanks on nearby Amaknak Island. There were some military photographers in the Aleutians, including longtime Arkansas Gazette photographer Larry Obsitnik. Many of his photos are included in various accounts of the Dutch Harbor raid. (Goldstein and Dillon) What is not well known even among family members is that Bob Johnson learned photography and darkroom skills while in the service and took several of the photographs displayed on the accompanying CD. Since he did not sign or identify which photos were his, it is impossible to tell which of the post-attack photos are his.

When the bombing and strafing stopped, the men came out to investigate the damage. The 206th Band ran down to do their appointed duties, helping attend to the wounded and dying (Bob Johnson, Boon) In Goldstein and Dillon’s book, there is a mention of one of the casualties, a bugler named Pfc. Allen C. “Cop” Collier. (Goldstein and Dillon) This possibly is the man that Dad spoke about as the friend who died in the war.

Though he didn’t identify the man by name, sometimes Dad spoke of one of his buddies, a man who did not survive the day. But he lived long enough to see Bob Johnson and to call out his nickname, “Bunny.” It is reasonable to assume that only those who knew him best, the musicians, would know him by sight and by that nickname.

Of that encounter Bob Johnson recalled that he came upon a couple of men, one that he knew well. The man was lying on his stomach and gasping for breath, his entire back blown off and his internal organs visible. Bob went to him to try to comfort him despite injuries that would prove fatal. His buddy called to him to “Turn me over, Bunny. I can’t breathe. Turn me over.” Dad said that he knew that to turn him over would kill the man, but that he only had minutes to live anyway. He crouched beside the soldier until he could no longer stand the pleas of the dying man.

“So I turned him over….and he was gone.” Bob didn’t tell that story much, maybe only once or twice. When he did, he had a catch in his voice and tears came to his eyes, as if it had happened only the day before. Clearly, the episode haunted him.

But there was no time for mourning. They had work to do. In addition to stretcher-bearing, the 206th had other pressing duties. One bomb had hit a transmitting antenna, a shelter trench, and a Quonset hut. Part of the Officer’s Club, a warehouse area used to store liquor was hit. Some officers’ barracks were gone, as was the wall that enclosed the liquor stores. Some of the men made off with the good bourbon and scotch before a guard could be posted. A few warehouses, including one full of undelivered Christmas presents, were destroyed. (Goldstein and Dillon)

On the way back to their carriers, two Japanese reconnaissance planes were shot down by American aircraft on patrol. It was suspected that several other planes sustained damage, but the Japanese got the better of the situation.

The commanders immediately got the men busy digging new foxholes and moving into new positions. A ground assault and naval invasion was expected to take place the next day or even that night. There was no time to waste. (Goldstein and Dillon)

Although he is given no credit for it in The Williwaw War, it was reported as fact by the men who were there (Johnson, Boon, Beauchamp, others) that Col. Elgan Robertson was responsible for saving the base and the men in it with a bit of military sleight of hand. Robertson called upon all the soldiers in the vicinity to report for assistance in moving gun emplacements and ammunition before the morning.

Robertson, who had fallen out of favor with many of the men due, one must gather, to his patrician attitude and bearing, as well as for some orders that no one could see the sense of. It was suspected that he was too “old school” for that modern war and was ineffective in being able to get the proper tools and weapons for his regiment. (Johnson, Goldstein and Dillon.)

However, whether it was old-time military training or just a hunch, Robertson’s orders to move everything proved to be effective. How effective? The Japanese dropped many bombs the next day, June 4, but these bombs hit the targets that had held gun emplacements and munitions on June 3. On June 4 anything important was camouflaged up in the hills and there were only dummy guns and empty buildings there when the Japanese struck a second time. (Goldstein and Dillon, p. 162)

Bob Johnson, courtesy of his daughter Stephanie Dixon

According to our father, “We all cussed Col. Robertson for making us stay up all night and work so hard. A lot of us couldn’t see the sense in it. But he knew what he was doing, and it saved us.”

When the necessary work was done, Robertson issued a message at 8:35 p.m. that “all positions must be occupied until relieved. Relief crews should get as much sleep as possible. All positions be on the alert for ground attack throughout the night. Everyone must be up by daylight. Be especially watchful for both high and hedge-hopping dive bombers should we have another air attack. Well pleased with work today.” (Goldstein)

The next day Robertson’s orders were to “be especially alert for small water craft and landing parties from now until dawn.” They were ready for the second attack. The irony was that there would have been no second attack if the Japanese plan had worked. Their plan was to make an air attack on the island of Adak to prepare for ground invasions. However, there was dense fog around Adak and there was supposed to be good visibility over Dutch Harbor.

Despite the damage done to Dutch Harbor the day before, the Japanese were not happy with the result. So they decided to go back and finish the job.

Most of the American munitions and guns had been placed on Mt. Ballyhoo, a 1,600 foot mountain given its name by Jack London. A good bit of the foxholes were there as well. Dr. Robert Boon has in his collection a picture of Mt. Ballyhoo. It sits at the mouth of the harbor at Dutch Harbor and is a very steep mountain, nearly vertical near the top. It is hard to imagine the American troops being able to maneuver their guns up that mountain in a year’s time, let alone overnight.

The troops waited on alert until they heard the first sirens. The Zeros came in thick and fast and the American soldiers fired at them with whatever they had to fire with. Some planes got hit, but were able to fly back out to sea. It is believed that some of the planes must have gone down in the sea. (USN Combat Narrative)

Bob Johnson said that he got “a real good look” at one pilot who flew at eye level with him. He fired upon the pilot, but didn’t know if he hit anything. Many of the new gun positions were hit that day but there were no casualties among their regiment. Col. Robertson’s bright idea worked.

There were casualties that day though. The Japanese dropped ten bombs on Mt. Ballyhoo, nine of which were not effective. One, however, hit near a magazine on the mountain, killing one officer and three enlisted men. (USN Combat Narrative)

It was on the second day that the hospital got hit and hit good. Since the patients and medical personnel had been moved, no one was hurt. More damage was done to fuel tanks at the harbor. The fire burned for 3 days. (Goldstein and Dillon) The bombers also hit a beached ship, The Northwestern (pdf), and it burned, “killing one million rats.” (Goldstein and Dillon)

Although it was a supply ship, that night Tokyo Rose reported that “Japanese bombers destroyed a warship at the Dutch Harbor pier.” (Goldstein and Dillon) Although the Americans weathered the second attack better, they had been no more effective against the Japanese the second day than they had the first. Their weapons were ineffective and outmoded. Six American soldiers and three sailors were killed that day. But the fuel tanks on Power House Hill and the ammunition magazine on Mt. Ballyhoo were intact.

During the two-day battle the American forces lost 33 Army, 8 Navy, 1 Marine, 1 civilian, and had 50 wounded. Twenty-five pilots and crew were lost. No one from the 206th was killed. (USN Combat Narrative, Goldstein)

Our fighter planes engaged some pilots from the Junyo over Unalaska. Each side lost two planes. The airfield had been a prime target and American pilots acknowledged that if a bomb had hit it there would be no more airfields in the Aleutians. (Goldstein and Dillon)

Some Japanese planes were hit over the airfields and did no damage to them, although a couple of American planes did go down in the dogfight. American pilots flew off Alaskan waters over the Japanese carriers and dropped bombs, thinking that they had been sunk. They hadn’t. The Japanese shipped sailed away without damage. Soon after the Japanese admiral Kakuta received a message concerning the Battle of Midway. It was a cryptic message stating that he should rendezvous with Japanese Vice Admiral Nagumo of the First Mobile Force. That force had four carriers with men who fought at Pearl Harbor and other places. Kakuta deduced that this wasn’t good news. (Goldstein)

The Japanese carriers turned away from the Aleutians and headed back. Later Admiral Yamamoto ordered Kakuta to attack Dutch Harbor by sea as had been planned, but by then the force was closing in on its meeting with Nagamo’s forces, and they were limping. (Goldstein and Dillon)

Fortunately for the American forces, an invasion didn‘t occur. They continued to plan for another attack and a possible ground invasion. (Goldstein and Dillon) Many believed that despite the fighting spirit of the Americans, there wasn’t enough ammo or sufficient artillery to stop the Japanese.

With only four hours of daylight left they attempted to take care of casualties and move the radar placements to better positions. The American soldiers were to move the artillery and to hide in the foothills of Unalaska. The AA guns were moved again, this time to the top of the mountain.

Roy Lee

Col. Robertson issued another order: "Be prepared and watchful during the night for seaborne attack. Be prepared for early morning air attack.” Subsequent calls to alert were rescinded when the planes spotted turned out to be ours. (Goldstein and Dillon)

Several of the men interviewed for Goldstein and Dillon’s book said that nearly everyone acquitted himself bravely and well, despite being poorly armed. One claimed that when they were sent to Dutch Harbor they were supposed to have been given a couple of 50 caliber anti-aircraft guns, which would have been very helpful. They had all been sent to Fairbanks instead. They felt that their guns were obsolete and about all they could do was “shoot at the planes with their rifles.”

Despite the damage done to facilities and the casualties, not much happened to change things on Dutch Harbor. At the end of the battle the Americans still controlled the island, the damage was repaired, and the Japanese carriers that attacked were prevented from being at Midway, where their presence could have changed the course of the war.

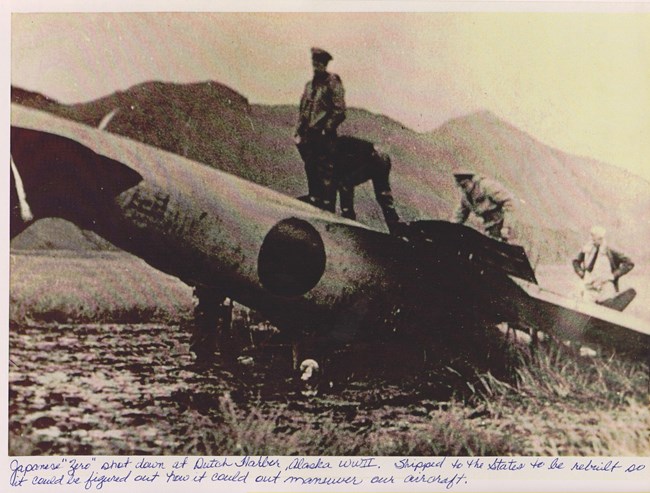

The Japanese lost nine planes, one of them fateful in the outcome of the war. One Zero, piloted by a man named Koga, landed at Akutan Island in order to be picked up by a Japanese sub after he ran low on fuel.

Dr. Boon remembered that luck ran out for that Japanese pilot and his Zero. When his plane was hit, “he tried to land with his landing gear down in that muskeg. His plane flipped and it broke his neck. But the plane was damaged very little. Our boys located it and brought it back to States. It was studied by our engineers, so we could build planes to overcome the Japanese advantage.”

After Americans discovered the plane, it sat undisturbed on the island until sleds could be brought in to drag it out. The plane had few bullet holes, one in the gas tank and there was damage to a propeller, which was repaired by the Americans when an American-made propeller was found to fit it. (Goldstein and Dillon)

It was an important find. The Japanese had clear air superiority up till then, thanks to the Zeros. But American engineers and test pilots were able to fix the plane, making it air-worthy again. They learned much of value about it, such as what features made it such a superb fighting plane and perhaps more valuable, what it’s deficiencies were. As a result, the U. S. made changes to its existing planes and learned how to fight against the Zeros. It is not a stretch to say that this knowledge was a crucial point to winning the war.

Although emotions must have run high during the attacks, all reports indicated that the men of the 206th and the other regiments at Ft. Myers performed as well as they could according to their training.

After the first attack, Dr. Boon said that the group he was with didn’t hear about people getting hurt till later. “But we saw camp burning and then we knew we needed to go help with clean-up. Our area just had strafing.” His assessment was that when the Japanese came on the second day, he supposed they had heard of the disaster at Midway and went to Attu to rest and resupply rather than to continue to attack Dutch Harbor.

Of Col. Robertson’s tactics between the two Japanese attacks, Boon confirmed that Robertson kept people up all night to move munitions. “It was rather miraculous. that they could move an entire gun battery and it’s position, but it was done….overnight. As a result, there were very few casualties and the Japanese bombed the old gun positions where no one was.”

Many days, even weeks later it became apparent that the Japanese were not planning another immediate attack on Dutch Harbor. Things slowly began to get back to normal.

This is Part 3 of "What Daddy and Mother did in the War." Read Part 4 next.

Last updated: July 18, 2025