Last updated: June 13, 2024

Article

Get to know Acadia's Precious Pollinators

Story and Illustrations by Jack Byrley

Whether you’re at Acadia to summit the most precarious peak, dip your toes in the chilly Atlantic water by the beach, or take a nice stroll through one of Mount Desert Island’s various historic gardens and museums, you would be hard-pressed to find any scenery unaffected by pollinators.

What is a pollinator? This word simply means anything responsible for carrying pollen from the male part of a flower (stamen) to the female part of another flower (stigma). Pollination can be accomplished through nonliving forces such as wind or water, as well as through animals such as insects, birds, bats, and more. Here, we will get to know a little more about some of the pollinators you may find at Acadia.

Bombastic Bumblebees

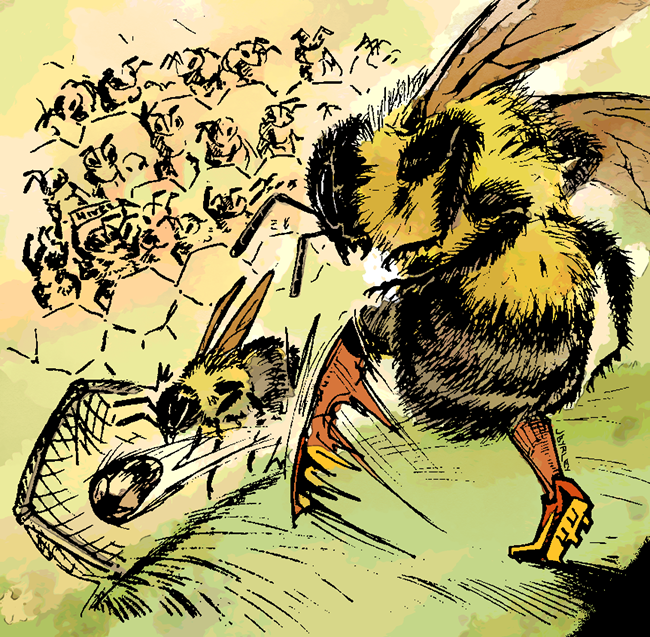

Has anyone ever told you you’re as busy as a bee? Acadia is home to eleven species of bumblebees. While bumblebees may look hard at work pollinating plants that feed us and beautify our landscapes, they also like to have fun. No, really—there is scientific evidence that bumblebees can, and do, goof off.

Researchers began an experiment intended to test a bumblebee’s intelligence. By puppeteering a small bumblebee-shaped figure, they demonstrated to their fuzzy students that pushing a tiny soccer ball into a goal would lead to a reward. The bumblebees not only were able to learn, but could teach bumblebees who had not seen the demonstration. Bumblebees developed different techniques for the game, showing that they weren’t simply mimicking their more experienced sisters. Even after the researchers had clocked out, bees would continue kicking the ball around. They had been given easy access to food and water, so it appears that their only motivation for continuing to interact with the ball is to have fun.

Wild bumblebees have not yet discovered how to manufacture tiny soccer balls, so you probably won’t see Acadian bees scoring goals. However, other studies have shown that various species of bees and wasps can count, use tools, and engage in play-fighting. We hope that the intelligence of these tiny superstars can help them continue to survive in a changing world.

Buzzing Beetles

Before butterflies and bees perfected pollination, there was the beetle. Beetles have frequented flowers for ~200 million years. The oldest known pollen-bearing bee fossil is only 30 million years old. Today beetles, like the adorably named bumble flower beetle (Euphoria india), still remain an important part of plants’ life cycles.

Beetles are “messy pollinators.” In addition to pollinating, they munch on leaves, drink sap, and even defecate in their host plants. The plants don’t seem to mind that last part. Some plants even have evolved specifically to attract beetles.

Beetle-pollinated plants tend to either be large and bowl-shaped to accommodate bulky beetles, like Acadia’s Yellow Pond Lily (Nuphar lutea), or be clusters of small exposed flowers like Seaside Goldenrod (Solidago sempervirens). Next time you sniff a flower, pay attention to the size, shape, and color- you might be able to clue in about the critter responsible for pollinating it.

Roly Poly Gardeners

It’s time to talk about the birds and the bees, and the… Isopods? Baltic Isopods (Idotea balthica) are underwater cousins to the roly-polies you might find in your garden. They are one of the only known underwater pollinators. Unlike their terrestrial cousins, these aquatic crustaceans are no homebodies.

A Baltic Isopod’s favorite food is algae, which can grow on seagrass, such as the eelgrass (Zostera marina) you can find offshore at Acadia. As they travel from seagrass to shining seagrass they carry spores, helping fertilize their new homes wherever they go. In return, seagrass and macroalgae provide isopods a safe haven for their young. One lab study showed that a tank containing algae and Baltic Isopods reproduced with 20% more efficiency than the tank without these 14-legged gardeners.

Although it’s hard to say if these numbers accurately reflect what goes on in Acadia’s chilly northern tidepools, the Baltic Isopod undoubtedly makes our underwater gardens a more lively, colorful place. Learn more about Acadia's tidepools here.

Hot-Blooded Hummingbirds

When you’re only 3.5 grams, have a heart that beats up to 1260 times per minute, and have one of the highest metabolic rates of any animal, you have no choice but to live fast. At least, that’s how the Ruby-Throated Hummingbird (Archilochus colubris) gets by. Ruby-throated hummingbirds are solitary- they need to consume twice their weight in nectar daily if they want to avoid starvation, so it makes sense they don’t like to share. Both males and females aggressively defend their territory from other hummingbirds, using their pointy beaks and agility to strike at opponents like aerial swordfighters. Ruby-throated hummingbirds can’t be found at Acadia year round, however. As nights get longer and temperatures drop, these hummingbirds migrate south of Maine and settle at the Gulf of Mexico, where they will continue to feed, fight, and fly until the great north calls to them once more.

Parental Paper Wasps

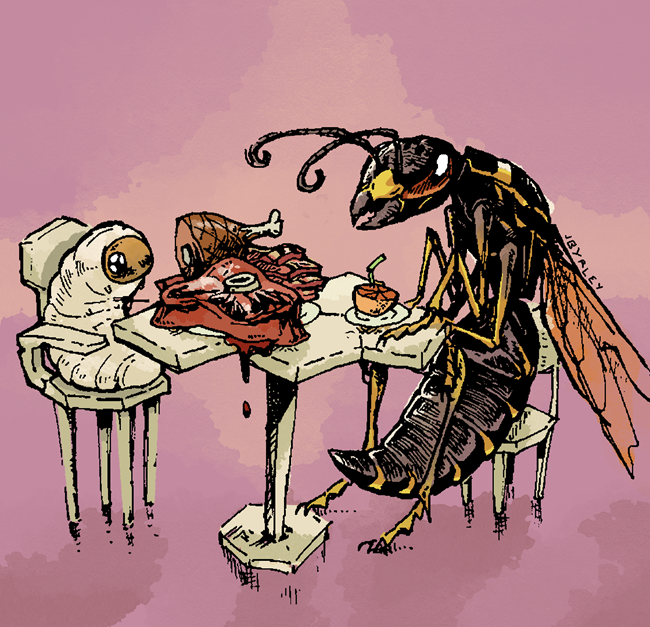

Do you have picky eaters in your family? You might have something in common with the Paper Wasp (Polistes fuscatus). Wasp colonies are smaller and more fluid than honeybee colonies, with multiple queens defending the nest and sterile female workers foraging to feed their larval younger sisters.

Adults have a sweet tooth, tracking down nectar, fruit, and sometimes that soda you brought to your picnic. Larvae need a protein-rich diet. Workers harvest carrion and hunt for pest insects such as mosquitos. On return, workers regurgitate a meaty concoction for the larva. This sounds gross, but wasps join wolves, condors, and penguins in this facet of parental care.

Paper Wasps may look scary and can deliver a painful sting if their home or family is being threatened, but wouldn’t you do the same? Think before you swat! Respect all wildlife at Acadia by watching quietly, respecting boundaries, and storing food properly.

Sly Flies

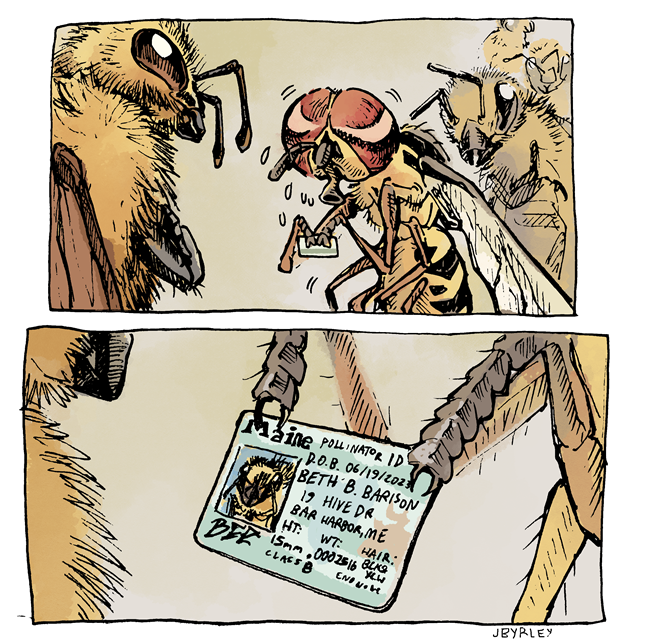

Things are not always as they appear in the world of pollinators, that black and yellow critter you see floating by a flower might not be a bee or wasp, but a hover fly (Syrphidae). Wait, no need to swat these little UFOs! Hover flies cannot bite, sting, poison, or otherwise defend themselves. Rather, they use “Batesian mimicry,” meaning they fool predators into thinking they are a more dangerous animal. Hover flies are not the only ones to have thought of this trick: moths, beetles, several other fly species, and even a species of spider, also don a bee-like disguise.

Greater bee flies (Bombylius major) are another pollinator fly you’ll find at Acadia. They take mimicry a step further, fooling even bees themselves. Unlike the timid hover fly, the bee fly is far from innocent: it uses cute, fuzzy looks to get close enough to lay its eggs by a bee or wasps’ nest, allowing the newborn fly larvae to hunt and feed on bee and wasp larvae. Pretty sly for a fly!

Want to see more beautiful flowers and busy bees in action? Visit the Wild Gardens of Acadia. A stroll through this community volunteer-run garden showcases the vast biodiversity found across Mount Desert Island. Over 300 native plant species make the Wild Gardens of Acadia a haven for wild animals and humans alike.

If you can’t visit the Wild Gardens of Acadia today, you can bring that same spirit home and cultivate your very own Wild Garden. 85% of U.S. households have outdoor space. Whether you have several acres or an urban window box, you can take steps to make your neighborhood safe for pollinators. There are many ways to make your home more pollinator-friendly:

- Cultivate nectar-rich flowers that are native to your area

- Abstain from the use of pesticides

- Let parts of your lawn grow wild to provide sheltar and nesting habitat

- Leave leaves on the ground for small animals

- Consider setting water out

Bees, birds, and other small animals are showing signs of decline. A variety of factors are to blame: climate change, pesticides, habitat loss, and more. It’s easy to feel powerless in the face of global issues, but taking steps to make your space habitable to pollinators has shown direct benefits in local communities.

To learn more about pollinators visit Pollinator.org, or discover how you can help pollinators in your own backyard.