Last updated: September 5, 2023

Article

Tidepool Tuesday

For a series of Tuesdays in summer of 2023, help Acadia celebrate its resident tidepool dwellers. Large and small, four legged or hundred-legged, squishy or rock solid, there's a place for them all!

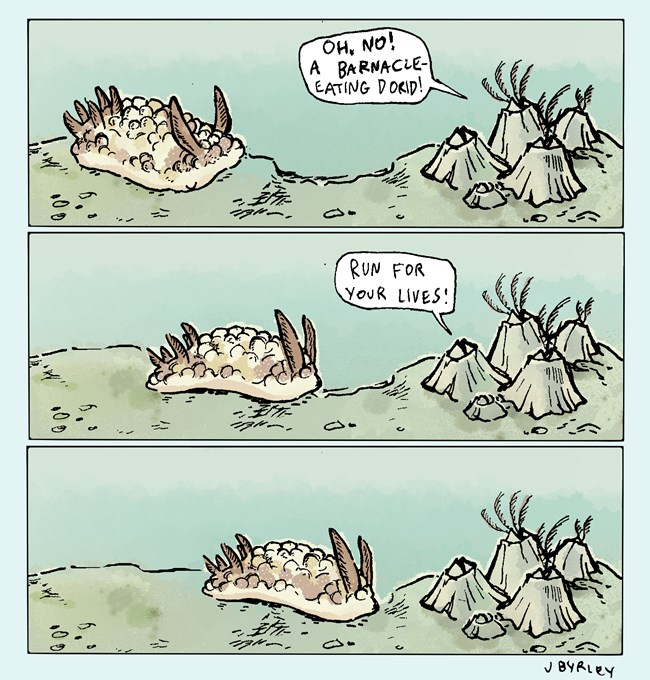

The Horrid Dorid

With its bunny ear-like tentacles, soft squishy body, and leisurely approach to life, you’d be forgiven for thinking that this sea slug is a gentle herbivore. However, it is actually a terrifying predator- at least, if you are a barnacle.The aptly named barnacle-eating dorid (Onchidoris bilamellata) prowls Acadia’s tidepools. Luckily for the slugs, barnacles are not known for speed. The tricky part is getting past the barnacles’ rock-hard shell. Barnacle-eating dorids have specialized radula, or mouth parts, to drill into the barnacle. If you keep snails in a home aquarium, watching them scrape algae off glass will give you a good look at radula in action. Imagine that, but scarier.

Unless you happen to be a barnacle, there isn’t much to fear. These slugs rely on camouflage to hide from predators. If you’re observant enough to spot one, we still recommend keeping your hands to yourself, for the slug’s safety, and watching it hunt (very slowly) from a distance.

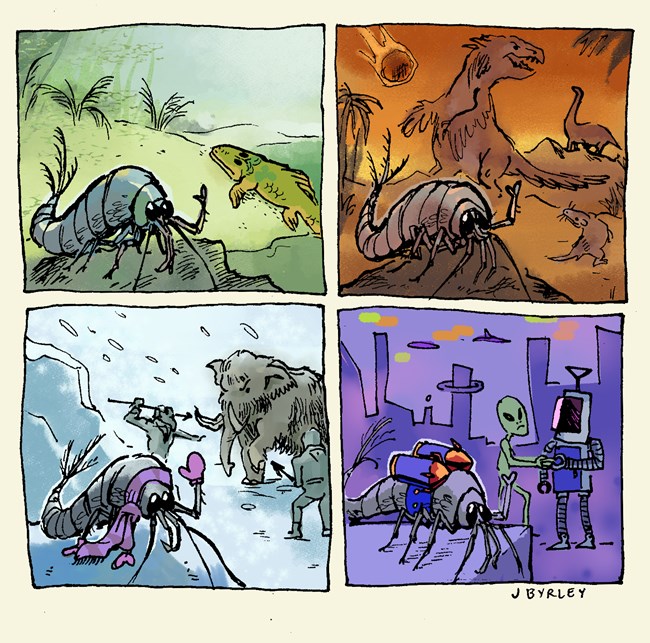

Bristletails and Beyond

Ever feel like you were born in the wrong generation? The western sea bristletail (Petrobius brevistylis) relates. They look like tiny shrimp and can be found on cliffs bordering Acadian tidepools, but are actually primitive insects.Bristletails are among the first land animals, inhabiting intertidal zones like you’d see at Acadia today. Only instead of sharing the beach with sunburnt humans, they emerged onto a lonely coast occupied by algae, fungi, and tiny arachnids. Fossilized bristletails date back to the Devonian period: meaning they survived four major extinctions and predate amphibians, trees, dinosaurs, and your great-grandma.

Bristletails aren’t going anywhere. Acadia’s species is nostalgic for the sea, but others inhabit alpine peaks, landlocked deserts, and deep caves. They live surprisingly long lives, taking two years to reach adulthood and may live a decade beyond that. Bristletails are a testament to “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

Must-See Mustilids

It’s always a delight to watch river otters (Lontra canadensis) play among Acadia’s lakes, tarns, and rivers. Unlike the sea otters of North America’s west coast, river otters prefer fresh water. However, much like Bar Harbor residents, no otter could say no to a seafood dinner. River otters have been observed at tidepools preying on crustaceans.Over a century ago, Acadia’s seafood-loving otters had competition. The sea mink (Neogale macrodon) was a ferret-like mammal that populated the Gulf of Maine. It was an important intertidal predator, hunting for fish, seabird eggs, and mollusks. They were renowned for luxurious fur and grew larger than inland minks. Sadly, this made them a target for fur traders. The last sea mink kill was in the late 1800s.

Unlike the threatened sea otter or extinct sea mink, the river otter is not currently a species of concern. It is abundant in Maine, but locally extinct in other states. The greatest threat to modern otters is pollution and habitat destruction.

Barnacle Brained

National parks have been known to attract drifters. However, few look as strange as the buoy barnacle (Dosima fascicularis). At first glance, this organism is hard to parse. Barnacles are arthropods: putting them in the same category as lobsters, honeybees, and millipedes. The family resemblance isn’t obvious. Each “head” is an individual animal, clustered around one nonliving raft.All barnacles begin as plankton: tiny organisms unable to fight against a current, but most species settle down into immobile adults. The buoy barnacle refuses to give up its drifter ways. Rather than settling on a rock, buoy barnacles attach themselves to driftwood, seaweed, marine animals such as sea turtles, and sadly, floating plastic. If they can’t find a raft they’ll make one, producing a porous substance similar to styrofoam.

With no legs or fins to swim with, buoy barnacles are subjected to the whims of the tides. Luckily, they don’t seem to mind going with the flow.

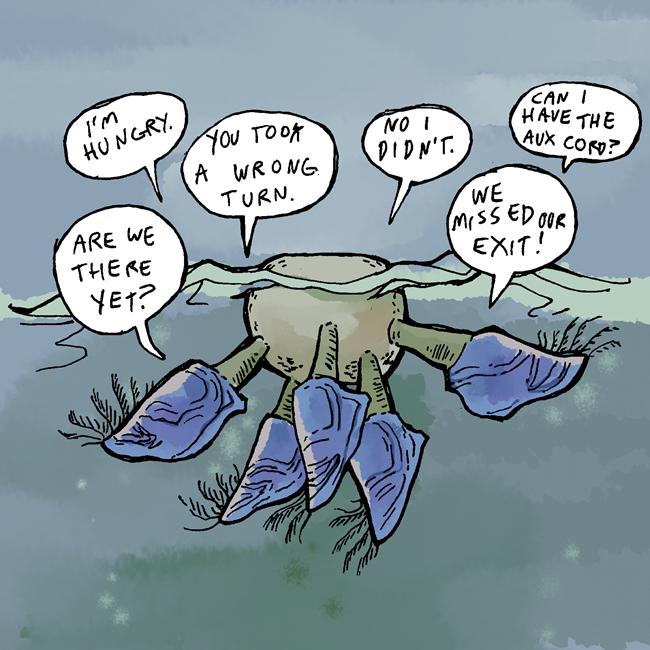

Chivalrous Crabs

The female Jonah crab (Cancer borealis) may seem hard on the outside, but on the inside she’s a big softie. Jonah crabs are one of the larger species you may see at Acadia’s tidepools, and are native to North America’s east coast.Crab courtship is a complex affair. Crabs molt their tough outer shells to grow, but are left soft and vulnerable until their new shell hardens. Female Jonah crabs mitigate this risk by releasing pheromones a few days prior to molting- think crustacean cologne, to attract a much larger male. After a courtship ritual, if the female approves of her suitor, he will guard her from predators and other males. Females even allow males to “embrace” them, and carry them from place to place in their claws.

The actual mating process takes place after the female has molted. The couple will then stay together for a week until the female’s new exoskeleton has hardened and then they will (amicably, we hope) part ways.

Thrifty Hermits

When it comes to reduce, reuse, and recycle, who else could be a better role model than the Acadian hermit crab (Pagurus acadianus)? Acadian hermit crabs have soft, vulnerable bodies. Unlike snails, hermit crabs cannot grow their own shells-- these thrifty crustaceans need to seek out empty shells.Much like you might outgrow your shoes when you’re young, or your favorite pair of pants when you’re older, Acadian hermit crabs, too, are forced to swap their shells. Some species of hermit crabs have been observed forming “conga lines,” from largest to smallest. The largest crab will vacate its shell, and the next size down will move in, and so on. Thrifting is not always so peaceful: it is also common for crabs to fight over a sought-after shell.

Do you have a favorite secondhand accessory? Whether it’s a beloved thermos adopted from a friend, a slick jacket scored at a thrift shop, or a hand-me-down from an older sibling, take a lesson from the Acadian hermit crab, and wear it with pride!

Pollinating Pillbugs

It’s time to talk about the birds and the bees, and the… Isopods? Baltic Isopods (Idotea balthica) are closely related to roly-polies you might find in your garden. They are one of the only known underwater pollinators. Unlike their terrestrial cousins, these sleek crustaceans are no homebodies.A Baltic Isopod’s favorite food is algae, which can grow on seagrass, such as eelgrass (Zostera marina) found offshore at Acadia. As they travel from seagrass to shining seagrass they carry spores, helping fertilize their new homes wherever they go. In return, seagrass and macroalgae provide isopods a safe haven for their young. One lab study showed that a tank containing algae and Baltic Isopods reproduced with 20 percent more efficiency than the tank without these 14-legged gardeners.

Although it’s hard to say if these numbers reflect what goes on in Acadia’s chilly northern tidepools, the Baltic Isopod undoubtedly makes our underwater gardens a more lively, colorful place. Learn more about Acadia's pollinators, land and sea, here.