Last updated: April 23, 2023

Article

Casey Barber

About The Author

Casey Barber is a visual storyteller who melds writing, illustration, and photography in pieces that spark the senses. Equally inspired by the local foodways and diverse landscapes of the United States, she explores the intersection of food and American culture with humor and insight.

Casey is the founder and editor of the website Good Food Stories and the author of two cookbooks: Pierogi Love: New Takes on an Old-World Comfort Food and Classic Snacks Made from Scratch: 70 Homemade Versions of Your Favorite Brand-Name Treats. Her work has appeared in numerous national publications and juried exhibitions, including the 2020 Rockefeller Center Flag Project.

She received a master’s degree from the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University, and a bachelor’s degree in English and visual art/art history from Bucknell University. When she’s not road-tripping, Casey lives in northern New Jersey with her husband and cats.

Visit her website at caseybarber.com and follow her on Instagram @goodfoodstories.

Live Text Transcript

Maine Ingredients: Recipes Inspired by Acadia National Park

Text, illustrations, and design © Casey Barber, Good Food Stories LLC

Introduction

This is a love letter to Acadia National Park. It’s an ode to every step taken through its deeply wooded paths and every twist and turn along its forested roads; every stacked granite outcropping; every quiet moment atop a summit or next to a softly rippling lake; and every whiff of brisk coastal air.

My 2022 Artist-in-Residence project draws on my work and passion as a food writer and artist to celebrate the ingredients and landscape of Acadia National Park, as well as Mount Desert Island and the Schoodic region.

During my residency, I explored the area’s local and traditional foods, which have been foraged and cultivated since the days of the first Wabanaki inhabitants through present-day producers supporting the region’s foodways via sustainable farming and aquaculture. I was also inspired by Acadia’s diverse natural surroundings, from the minerality of the rocks to the scent of juniper on the breeze and the salinity of the Atlantic ocean.

These Maine ingredients aren’t just ones you can taste and smell—they’re a full five-sense experience. It’s that all-encompassing sensory feeling I hope to share through this project.

Thank you to the National Park Service for giving a food writer an artist-in-residency spot and an opportunity to showcase Acadia through these essays and recipes. Special thanks to Jay Elhard and Alison Richardson of the NPS, Michelle Pinkham of the Schoodic Institute, and Sam Mallon of Friends of Acadia.

Thank you to the Indigenous communities, including the Abenaki, Maliseet, Micmac, Passamaquoddy, and Penobscot Nations, who have sustained this land and its foodways for millennia. I recognize and support the ongoing contributions of these tribes to the cultural landscape of the region.

I thought I knew Acadia well after multiple visits over the past 15 years, but being an Artist-in-Residence has gifted me with a deeper and richer connection to the park than I ever hoped possible. The time spent with the luxury to immerse myself in the Acadia region makes it now truly feel like home.

Cadillac Mountain Sunrise

I really thought we were going to miss out on the sunrise.

It sounded like the perfect experience when I realized the timing of our June stay in Acadia would allow us to take in the sunrise from the summit of Cadillac Mountain on the summer solstice—the longest day of the year.

Wapuwoc, the Indigenous name of Cadillac Mountain, translates to “white mountain of the first light.” And as the Wabanaki are the People of the Dawn, “the ability to see the sunrise from the summit of Wapuwoc before anywhere else in the Dawnland has always given the mountain spiritual significance in Wabanaki culture,” wrote Passamquoddy artist and educator Geo Neptune in their paper “Naming the Dawnland.”

Technically we weren’t seeing the first light in the United States in the summer, since the mountain summit only receives that honor from October through March. But I wasn’t about to let small details like that get in the way of my oh-so-great idea.

Even though we got on the road from Schoodic at 3 a.m., I could already catch glimpses of glowing pink coming from the horizon off the water. I freaked out the whole way to the park entrance, convinced I had somehow misjudged the timing.

Spoiler alert: We did not miss the sunrise. According to the board at the ranger gate, where we were one in a long line of cars crawling up the side of the mountain like patient ants, first light was at 4:12 a.m.

Cadillac, or Wapuwoc, is not a place to see a summer solstice sunrise in solitude, but the show doesn’t disappoint in the least because of its popularity. The slow burn of persimmon and ochre across the line of the horizon bleeds into the fading indigo of the heavens, imperceptibly spreading minute by minute, until all at once, a shining line of lava hits the top of the mountains across the Mount Desert Narrows.

The Cadillac Mountain Sunrise cocktail takes its inspiration in equal parts from an Aperol Spritz and a Tequila Sunrise, making it a drink you could very well appreciate while witnessing the actual crack of dawn.

Blueberry syrup gives the beverage its deeply hued base, and if you’re in Acadia after the summer solstice, chances are you’ll be able to get your paws on some fresh local blueberries with which to make your syrup.

If that’s not the case, don’t fret. Frozen Maine blueberries work just as well in this recipe, so you’ll be able to make it for the winter solstice too.

Prep Time: 10 minutes

Cook Time: 10 minutes

Additional Time: 1 hour

Blueberry Syrup

- 4 ounces (113 grams) fresh or frozen Maine blueberries

- 1/2 cup (100 grams) granulated sugar

- 2 tablespoons water

- 1/2 cup (4 fluid ounces) freshly squeezed and strained orange juice

- 1 tablespoon (1/2 fluid ounce) blueberry syrup

- 2 tablespoons (1 fluid ounce) Aperol

- 1/4 cup + 2 tablespoons (3 fluid ounces) sparkling wine

Add the blueberries, sugar, and water to a small (1-quart) saucepan, and bring to a simmer over medium-low heat.

Cook, stirring frequently, for about 5 minutes, until the blueberries are very soft and easily smashed against the side of the pan.

Strain the syrup through a fine mesh strainer—you’ll have about 1/2 cup syrup, enough for 8 drinks.

Cool the syrup to room temperature for 1 hour, or chill overnight before making cocktails.

Make the cocktail:

Fill a 12-ounce highball glass halfway with ice.

Pour the orange juice over the ice.

Pour the blueberry syrup down the side of the glass so it settles to the bottom.

Pour the Aperol the same way as the blueberry syrup—it will settle on top of the syrup.

Add the sparkling wine—it will float on top.

Admire the layers of color, then stir before sipping the drink.

Blueberry Buckwheat Ployes With Spruce Honey

Acadia. Mount Desert. Sieur de Monts. Isle au Haut. I studied French, so I see the influence of France’s colonial input every time I read a map or sign around the area.

The etymology goes a little something like this: The island known to the native Wabanaki tribes as Pemetic, on which the bulk of the National Park sits, was colonized and dubbed “Ile de Monts Deserts,” or “island of bare mountains” by French explorers in the 17th century.

Sieur de Monts National Monument, named after one of the explorers, was established in 1916 and renamed Lafayette National Park when it got the upgrade in 1919. (Listen, people, he really was America’s favorite fighting Frenchman!) The park’s name changed again to Acadia in 1929, and so it has been ever since.

Beyond the nomenclature, more long-lasting French-Acadian traditions are evident as you travel north and west through Maine and into Canada. If you know the The Band’s song “Acadian Driftwood,” you know the history of how French colonists were sent packing by the British and eventually made their way to Louisiana, where the word “Acadian” was regionalized to “Cajun.”

Ployes (pronounced ployz) are one of those culinary traditions. They’re an Acadian specialty, a simple pancake-crepe hybrid made with buckwheat flour. They’re characterized by their lacy “eyes”—a whole bunch of tiny bubbles that start popping up in the batter as soon as it hits a hot griddle.

They’re even easier to make than pancakes, since there are neither eggs nor dairy involved in the traditional recipe. All you need is a mix of buckwheat and all-purpose flour, baking powder to give each ploye a little bounce, and water.

You can enjoy ployes as you would pancakes or waffles, topped with maple syrup and fruit, or serve them as you would tortillas, cornbread, or rolls alongside savory stews, chowder, and chili.

Here, I like to make a breakfast batch of ployes sweetened with maple sugar and cinnamon, and topped with fresh Maine blueberries and a simple spruce-infused honey. If you don’t feel like making spruce honey, maple syrup is always a good bet.

Prep Time: 10 minutes

Cook Time: 15-25 minutes

- 1 cup (120 grams) buckwheat flour

- 1/3 cup (40 grams) all-purpose flour

- 2 teaspoons baking powder

- 1 teaspoon maple sugar (optional)

- 1/2 teaspoon kosher salt

- 1/2 teaspoon ground cinnamon (optional)

- 1 cup cold water

- 3/4 cup boiling water, divided

- Fresh Maine blueberries, for topping

- Spruce honey, for topping

Whisk the buckwheat and all-purpose flours, baking powder, maple sugar, salt, and cinnamon together in a bowl.

Whisk in the cold water to make a thick batter.

Whisk in 1/2 cup boiling water, then whisk in the additional 1/4 cup water a few tablespoons at a time as needed until the batter is thin. The consistency should be very liquid, like buttermilk or half and half.

Ladle 1/4 cup batter onto the preheated skillet or griddle.

The batter should sizzle and bubble as soon as it hits the griddle, and bubbly, lacy “eyes” should immediately start popping up in the batter.

Cook until the top of the ploye is matte and dry and the edges are curling up, about 2-3 minutes.

Serve the ployes immediately, topped with fresh Maine blueberries and spruce honey.

To make spruce honey:

Add about 1/2 ounce (14 grams) fresh spruce tips to an 8-ounce Mason jar.

Fill the jar with honey and let it sit for at least 2 weeks and up to 1 month to let the spruce flavor infuse the honey.

Strain the honey through a fine mesh strainer into a clean jar before using.

Smoked Dulse Crackers

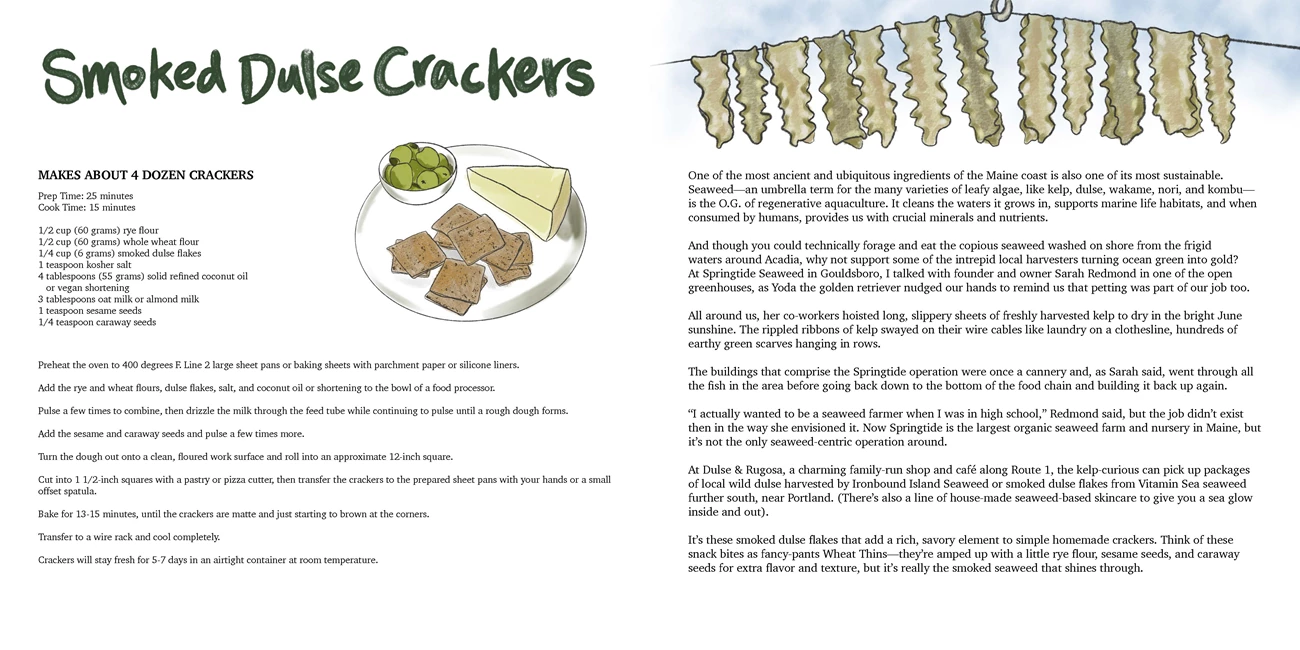

One of the most ancient and ubiquitous ingredients of the Maine coast is also one of its most sustainable. Seaweed—an umbrella term for the many varieties of leafy algae, like kelp, dulse, wakame, nori, and kombu— is the O.G. of regenerative aquaculture. It cleans the waters it grows in, supports marine life habitats, and when consumed by humans, provides us with crucial minerals and nutrients.

And though you could technically forage and eat the copious seaweed washed on shore from the frigid waters around Acadia, why not support some of the intrepid local harvesters turning ocean green into gold?

At Springtide Seaweed in Gouldsboro, I talked with founder and owner Sarah Redmond in one of the open greenhouses, as Yoda the golden retriever nudged our hands to remind us that petting was part of our job too.

All around us, her co-workers hoisted long, slippery sheets of freshly harvested kelp to dry in the bright June sunshine. The rippled ribbons of kelp swayed on their wire cables like laundry on a clothesline, hundreds of earthy green scarves hanging in rows.

The buildings that comprise the Springtide operation were once a cannery and, as Sarah said, went through all the fish in the area before going back down to the bottom of the food chain and building it back up again.

“I actually wanted to be a seaweed farmer when I was in high school,” Redmond said, but the job didn’t exist then in the way she envisioned it. Now Springtide is the largest organic seaweed farm and nursery in Maine, but it’s not the only seaweed-centric operation around.

At Dulse & Rugosa, a charming family-run shop and cafe along Route 1, the kelp-curious can pick up packages of local wild dulse harvested by Ironbound Island Seaweed or smoked dulse flakes from Vitamin Sea seaweed further south, near Portland. (There’s also a line of house-made seaweed-based skincare to give you a sea glow inside and out).

It’s these smoked dulse flakes that add a rich, savory element to simple homemade crackers. Think of these snack bites as fancy-pants Wheat Thins—they’re amped up with a little rye flour, sesame seeds, and caraway seeds for extra flavor and texture, but it’s really the smoked seaweed that shines through.

Prep Time: 25 minutes

Cook Time: 15 minutes

- 1/2 cup (60 grams) rye flour

- 1/2 cup (60 grams) whole wheat flour

- 1/4 cup (6 grams) smoked dulse flakes

- 1 teaspoon kosher salt

- 4 tablespoons (55 grams) solid refined coconut oil or vegan shortening

- 3 tablespoons oat milk or almond milk 1 teaspoon sesame seeds

- 1/4 teaspoon caraway seeds

Add the rye and wheat flours, dulse flakes, salt, and coconut oil or shortening to the bowl of a food processor.

Pulse a few times to combine, then drizzle the milk through the feed tube while continuing to pulse until a rough dough forms.

Add the sesame and caraway seeds and pulse a few times more.

Turn the dough out onto a clean, floured work surface and roll into an approximate 12-inch square.

Cut into 1 1/2-inch squares with a pastry or pizza cutter, then transfer the crackers to the prepared sheet pans with your hands or a small offset spatula.

Bake for 13-15 minutes, until the crackers are matte and just starting to brown at the corners.

Transfer to a wire rack and cool completely.

Crackers will stay fresh for 5-7 days in an airtight container at room temperature.

Fiddlehead Fritti

“I’m glad you’re doing it and not me.” “That sounds fun… for you…” “We lead very different lives sometimes.”

Somehow the idea of hiking 2 1/2 miles each way to a ranger cabin with no electricity or running water—while carrying everything we’d need for two days and nights—didn’t seem as enticing to my friends as it did to me. But I couldn’t resist the chance to see a part of Acadia National Park that very few others do.

Isle au Haut is an island with about 12 1/2 square miles of land, nearly half of which has been part of Acadia National Park since 1943. With fewer than 100 year-round residents on the island and scant amenities, it’s one of the most rustic experiences one can have as a park visitor.

Ranger Alison Richardson (an Isle au Haut native) took some of the burden off our backs by offering to haul us from the ferry dock to the cabin in her Kubota UTV. We gratefully took the ride and bounced our way uphill.

The cabin overlooks Eli Creek, and it’s no writerly exaggeration to say this picture-perfect vista could not have been designed by Disney Imagineers to be any more scenic than it naturally is. The creek chattily burbles down cascading rocks, under a footbridge on the Duck Harbor Trail and into a cove flowing out to Moores Harbor.

With only a general store, post office, small gift shop, and ranger station on the main road, hiking is the main to-do when visiting Isle au Haut. The challenging terrain, with miles of trails covered in roots and rocks, was enveloped in lush shades of green during our early September visit.

Under a spruce and pine canopy, we crisscrossed bog bridges, our boots bending the wooden planks that took us over blankets of sundew and moss. Even a slender squiggle of an emerald snake showed its brilliance to us as we descended the Western Head Trail.

Nature provided the floor show for our two electricity-free evenings. From the cabin porch, we watched the sun shoot beams of gold through the tree canopy as it sank to the horizon. For the grand finale of the sunset, we walked a few yards downhill to the creek bridge as sky and harbor mirrored each other in a slow burn of pink and orange.

Ferns are part of the verdant landscape of Acadia, from the mainland to the islands of Mount Desert and Isle au Haut. Though most aren’t foraged for food, fiddleheads—the curled-up immature fronds of the ostrich fern—are a spring delicacy.

This recipe is inspired by Italian fritto misto, where vegetables and seafood are fried in a light and crispy tempura-style batter. In this quick-fry method, the fiddleheads retain their snappy texture and delicately fresh flavor.

Prep Time: 10 minutes

Cook Time: 30 minutes

Aioli

- 1/4 cup mayonnaise

- 2 teaspoons freshly squeezed lemon juice

- 1/8 teaspoon kelp seasoning

- 1 pound fiddlehead ferns 1 quart organic canola oil

- 1 cup (142 grams) rice flour

- 1 cup (113 grams) cornstarch

- 2 teaspoons baking powder

- 1 teaspoon kosher salt, plus more for seasoning

- 2 cups ice-cold plain seltzer

Rinse the ferns well in a colander, then pat dry on a cotton towel. Snap off any browned stem ends.

Pour the oil into a medium (3 1/2-to 5-quart) Dutch oven. It should not reach more than halfway up the sides of the pot.

Heat the oil to 350 degrees F over medium heat.

Make a fry draining station by lining a large rimmed sheet pan with paper towels and placing a cooling rack upside-down on the paper towels to weigh them down.

While the oil heats, whisk the rice flour, cornstarch, baking powder, and salt together in a large bowl.

When the oil comes to temperature, whisk the seltzer into the dry ingredients to form a thin batter.

Add the fiddlehead ferns to the batter, tossing with your hands to coat.

A handful at a time, carefully add the battered ferns to the hot oil. Fry for 1-2 minutes, just until the batter is crisp and puffy.

With tongs or a metal spider, transfer the fried ferns to the draining station.

Season with a sprinkle of kosher salt and serve with the aioli for dipping.

Cider-Steamed Clams and Mussels

Everyone automatically associates lobsters with Maine, but clams are literally the first name in shellfish when it comes to the Acadia area. Literally! The Wabanaki name for what is now called Bar Harbor is Moneskatik, which translates to “the place where clams are dug,” “the clam digging place,” or “clam gathering place,” based on various sources. If you want to eat local, you can’t get more authentic than slurping down a bunch of bivalves that have been harvested in the region for millennia.

In this spirit of authenticity, I wanted so badly to dig up a few dozen clams for my dinner while in residency. So I rolled into Schoodic in June equipped with a garden rake, a bucket, and a pair of bright pink wellies.

Trying to determine a place where I could dig that wasn’t hampered by red tide, I stopped by The Lobstore seafood market in Winter Harbor and eavesdropped on one customer inviting another to pick mussels on their property. Hoping to score my own invite, I asked about the best digging locations and was advised by Tiffany at the register of a spot in Sullivan—“you go over the bridge by the Dollar General and right there by the building that kind of looks abandoned, you know?”

Though I later figured out she was referring to the area near Tidal Falls Preserve, a shellfish-rich shoreline teeming with blue mussels, crabs, starfish, and no doubt many other tidepool creatures, I decided to cut my losses (and save my $20 fee for a non-resident shellfish permit) and buy clams directly from Tiffany.

Historically, clams and mussels were often smoke- or air-dried for winter storage in Indigenous communities, but I prefer to eat mine steamed in an aromatic broth. And while white wine is always an excellent partnah when it comes to steaming shellfish, I decided to steam mine in cidah this time around.

Yep, cidah, as the label on the Urban Farm Fermentory can reads. This Portland-based fermented beverage producer makes a seaweed-infused cidah with a subtly briny undercurrent, as well as a more traditional dry cidah for the less adventurous. Closer to Acadia, Deer Isle Cider Company uses foraged wild and heirloom apples for their cider.

If you’re buying local to where you are, just make sure your cider is dry—not sweet— and that your clams and mussels are as fresh as possible. You don’t need much else, other than good crusty bread for dunking, for a truly satisfying meal.

Prep Time: 20 minutes

Cook Time: 10 minutes

- 1 (50-count) bag littleneck clams or (2-pound) bag blue mussels

- 2 tablespoons unsalted butter 2 large garlic cloves, minced 1 medium shallot, minced

- 1 cup (8 fluid ounces) dry cider

- 1 loaf crusty sourdough or French bread, thickly sliced

Rinse and scrub the clams or mussels with a vegetable brush or an old toothbrush to remove any exterior grit. If the mussels have any errant beards (little grassy fuzz) sticking out of their shells, yank those off too.

Melt the butter in a medium (3-quart) stainless steel saucepan or enameled Dutch oven over medium heat.

Add the garlic and shallot and cook for about 3 minutes, until the shallot has softened.

Increase the heat to medium-high heat and add the clams or mussels and cider.

Cover and simmer for 8-10 minutes until all the shells have opened. (There are always one or two outliers that never open; you gotta ditch them for your own health and safety.)

While the clams and mussels steam, arrange the sliced bread on a sheet pan and toast in the oven.

Serve the bivalves and broth immediately with the warm bread.

Cold Crab Shio Ramen

The crab wedged itself under a canopy of waving kelp at Tidal Falls Preserve, statue-still in its shady nook while kids splashed and shrieked over starfish a few yards away.

The starfish might have been the big draw for nearly everyone tromping slowly, heads bowed, along the shoreline. But I was drawn to the crab’s ruddy shell as it rested in relative peace under its fluttering awning of olive green.

Jonah and Atlantic rock, AKA peekytoe, crabs are the two local species of tasty crustacean found along the Maine coast—and the ones you’ll likely be savoring in your generously stuffed crab rolls. (Red crabs swim out further, in the deep and icy waters further offshore).

What I spied at Tidal Falls Preserve was likely a rock crab, which is smaller than the Jonah crab and loves to hang out in bays, rivers, and rocky tidepools.

The gulls were even better at spotting the crabs than I was, grabbing them roughly and smashing them against the rocks for an al fresco snack, then flapping off to leave the detritus for any other creature to discover.

I’d rather have my crab lightly cooked instead of raw and smashed against a rock, but I do love the idea of cool crab on a hot summer day. This recipe for cold shio—or salt—ramen was inspired by a dish I used to eat at Ivan Ramen in New York, a summer splurge on sticky city afternoons.

The soup is a study in refreshment, with flakes of fresh crabmeat strewn over bouncy ramen noodles and bright lemon in the delicately saline broth. I use two kinds of Maine-harvested seaweed in this dish: kombu for the broth and a handful of kelp ribbons tossed over the dish just before serving.

You’ll get a hit of brine in every bite to complement the sweet crab and corn.

Prep Time: 15 minutes

Cook Time: 20 minutes

Additional Time: 3 hours

Ramen Broth

- 1 tablespoon sesame oil

- 1 tablespoon vegetable oil

- 1/2 ounce (14 grams) grated fresh ginger

- 1 large garlic clove, minced or grated

- 1 large or 2 small scallions, finely chopped

- 1 3- to 4-inch square of kombu

- 1 tablespoon mirin

- 1 tablespoon kosher salt

- 4 cups (1 quart) water

- 1 tablespoon freshly squeezed and strained lemon juice

- 4 (4- to 5-ounce) packages ramen noodles (fresh, frozen, or dried)

- Kernels from 1 large ear of fresh corn

- 8 ounces Maine crabmeat

- 1 large scallion, green parts only, sliced

- Dried kelp ribbons

Heat both oils in a 2-quart saute pan over medium-low heat.

Stir in the ginger, garlic, scallions, and kombu. Cook for about 30 seconds, stirring constantly.

Add the mirin, salt, and water. Bring to a simmer and cook for 10 minutes, then remove from the heat and let cool to room temperature.

Transfer to a lidded container and refrigerate for at least 3 hours, until chilled.

Discard the kombu and stir in the lemon juice just before you’re ready to serve the broth with the noodles.

Make the ramen:

Bring a medium (4-quart) pot of water to a boil and cook the ramen noodles for 2-3 minutes until bouncy and al dente.

During the last minute of cooking, add the corn kernels.

Drain the noodles and corn in a colander and run under cool water to stop the cooking process.

Divide between 4 shallow bowls, then ladle the chilled broth over the noodles and corn.

Top each mound of noodles with 2 ounces crabmeat, and sprinkle the scallions and a pinch of kelp ribbons over each bowl.

Beach Rose Panna Cotta

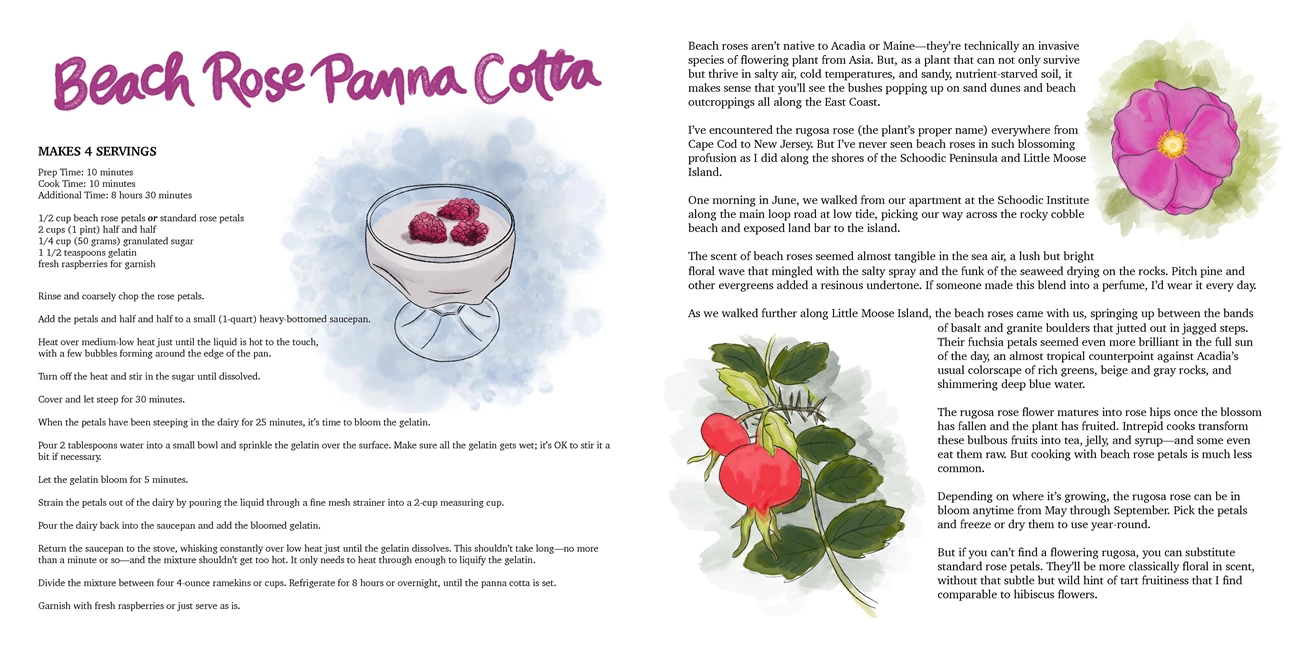

Beach roses aren’t native to Acadia or Maine—they’re technically an invasive species of flowering plant from Asia. But, as a plant that can not only survive but thrive in salty air, cold temperatures, and sandy, nutrient-starved soil, it makes sense that you’ll see the bushes popping up on sand dunes and beach outcroppings all along the East Coast.

I’ve encountered the rugosa rose (the plant’s proper name) everywhere from Cape Cod to New Jersey. But I’ve never seen beach roses in such blossoming profusion as I did along the shores of the Schoodic Peninsula and Little Moose Island.

One morning in June, we walked from our apartment at the Schoodic Institute along the main loop road at low tide, picking our way across the rocky cobble beach and exposed land bar to the island.

The scent of beach roses seemed almost tangible in the sea air, a lush but bright floral wave that mingled with the salty spray and the funk of the seaweed drying on the rocks. Pitch pine and other evergreens added a resinous undertone. If someone made this blend into a perfume, I’d wear it every day.

As we walked further along Little Moose Island, the beach roses came with us, springing up between the bands of basalt and granite boulders that jutted out in jagged steps. Their fuchsia petals seemed even more brilliant in the full sun of the day, an almost tropical counterpoint against Acadia’s usual colorscape of rich greens, beige and gray rocks, and shimmering deep blue water.

The rugosa rose flower matures into rose hips once the blossom has fallen and the plant has fruited. Intrepid cooks transform these bulbous fruits into tea, jelly, and syrup—and some even eat them raw. But cooking with beach rose petals is much less common.

Depending on where it’s growing, the rugosa rose can be in bloom anytime from May through September. Pick the petals and freeze or dry them to use year-round.

But if you can’t find a flowering rugosa, you can substitute standard rose petals. They’ll be more classically floral in scent, without that subtle but wild hint of tart fruitiness that I find comparable to hibiscus flowers.

Prep Time: 10 minutes

Cook Time: 10 minutes

Additional Time: 8 hours 30 minutes

- 1/2 cup beach rose petals or standard rose petals

- 2 cups (1 pint) half and half

- 1/4 cup (50 grams) granulated sugar

- 1 1/2 teaspoons gelatin

- fresh raspberries for garnish

Rinse and coarsely chop the rose petals.

Add the petals and half and half to a small (1-quart) heavy-bottomed saucepan. Heat over medium-low heat just until the liquid is hot to the touch, with a few bubbles forming around the edge of the pan. Turn off the heat and stir in the sugar until dissolved.

Cover and let steep for 30 minutes.

When the petals have been steeping in the dairy for 25 minutes, it’s time to bloom the gelatin.

Pour 2 tablespoons water into a small bowl and sprinkle the gelatin over the surface. Make sure all the gelatin gets wet; it’s OK to stir it a bit if necessary.

Let the gelatin bloom for 5 minutes.

Strain the petals out of the dairy by pouring the liquid through a fine mesh strainer into a 2-cup measuring cup.

Pour the dairy back into the saucepan and add the bloomed gelatin.

Return the saucepan to the stove, whisking constantly over low heat just until the gelatin dissolves. This shouldn’t take long—no more than a minute or so—and the mixture shouldn’t get too hot. It only needs to heat through enough to liquify the gelatin.

Divide the mixture between four 4-ounce ramekins or cups. Refrigerate for 8 hours or overnight, until the panna cotta is set.

Garnish with fresh raspberries or just serve as is.