Last updated: February 14, 2025

Article

"A Sacrifice of Inclination": Samuel Longfellow

Longfellow Family Photograph Collection (3007.004/002.003-#006)

In 1835, Henry Longfellow’s youngest brother, Samuel Longfellow (1819-1892), moved to Cambridge and began attending Harvard College. Samuel was a minister, and abolitionist, pacifist, and a supporter of women’s rights. Whenever his ministerial duties or travels didn’t take him away, Samuel Longfellow lived at the Vassall-Craigie-Longfellow House, and he was by all accounts a constant and beloved presence in the home. His correspondence, and the relationships he formed over the course of his life, point to the complexities of the gay experience in New England in the 1800s.

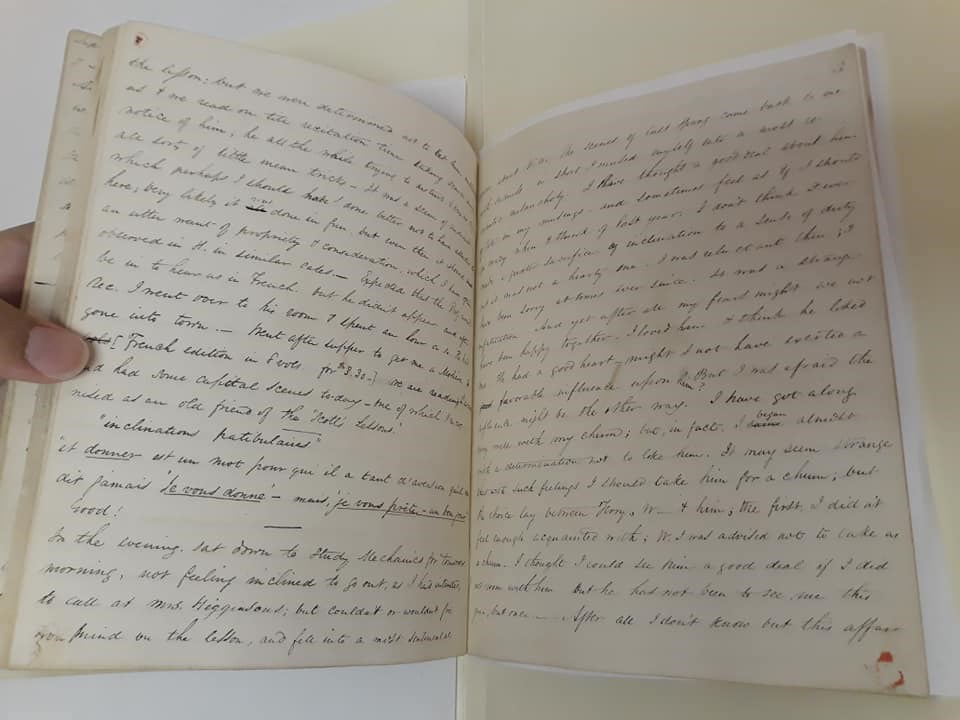

From the letters and few journals he left behind (he destroyed many of them before he died)1, it appears as though Longfellow struggled to make peace with his sexuality early in life. His first major infatuation occurred while he was still in college. In 1837, Longfellow wrote a long passage in his journal – the pages later sealed with wax – about a fellow classmate named William Winter, later sealed with sealing wax. Despite being “friends” for over a year, this is the very first time that Longfellow had ever written about him – just when the friendship had seemingly come to an end:

Fell into a most sentimental reverie about W.W. The scenes of last spring came back to me with sadness- in short I mused myself into a most romantic melancholy. I have thought a good deal about him of late in my musings- and sometimes feel as if I should go crazy when I think of last year. I don’t think I have made a greater sacrifice of inclination to a sense of duty- but not a hearty one- I was reluctant then; I have been sorry at times ever since. It was a strange infatuation. And yet after all my fears might we not have been happy together? I loved him, and think he liked me.2

Reverend Samuel Longfellow Papers, Longfellow House - Washington's Headquarters NHS

A year later, Winter returned once more, with Longfellow writing, “Willie Winter came in and staid awhile. For whom my passion is revived. I sit next to him at table and look into those eyes of his full of fun.” A day later, exhausted from his schoolwork, he recorded in his journal, “Am too sleepy to read over Sound so will leave it till morning and go to sleep to dream of --------’s eyes.”3

Despite their mutual feelings, Longfellow’s infatuation with Winter remained complex, and in the end the two drifted apart. Winter married and moved to Mississippi, and Longfellow went on to attend Divinity School. Samuel Longfellow’s fear of a more intense relationship, and the pains he took to hide all evidence of it, is telling. Romantic friendships were the norm of the day, allowing for same-sex friends to confess their love, kiss, and even share beds.4 As a student at Harvard and a young man in Cambridge, these types of friendships would have been common, and even unremarkable. In that context, Longfellow may have felt that his own feelings for Winter went far beyond what society deemed acceptable, and required that he distance himself from Winter altogether. As he got older, those anxieties were slowly replaced with a seemingly cautious acceptance, especially after a different William began appearing in his writings.

Longfellow first met William Shaw Tiffany, an undergrad at Harvard and aspiring artist, around 1843. The first insight we have into Longfellow’s feelings for Tiffany occurred on New Year’s Day of 1845, when Longfellow began keeping a new journal. “On my way home,” he happily wrote, “I stopped in at William’s room to give him a little volume of Emerson as a New Year’s gift & pledge of love.”5

Longfellow wrote quite a bit about Tiffany throughout January – afternoon teas, romantic strolls, evenings spent together, and his increasing frustration at being unable to get Tiffany all to himself.6 Though it must have still been difficult to process his feelings in this time, much of the fear from his teenage years vanishes altogether in these entries. On January 16, 1845, Longfellow boldly wrote about a very special moment – his first kiss:

William left for Baltimore – I went down to say goodbye… Dear William, I trust nothing from without or within will interfere with his complete success. – As I said good bye, I kissed his round cheek – my first kiss; dear William – my blessing goes with you.7

Though quaint by today’s standards, a loving kiss on the cheek was worlds away from Longfellow’s earlier “sacrifice of inclination,” and was perhaps a first step into embracing his feelings. Much like William Winter, William Tiffany also went on to marry and start a family. Though the infatuation seems to have receded, their friendship remained, and a correspondence continued off and on between Samuel Longfellow and William Tiffany for decades.

Out of everyone, the most enduring—though ambiguous—relationship in Longfellow’s life was with Samuel Johnson. Longfellow first met Johnson in 1842, when Johnson was giving a speech in Harvard Yard. He immediately found himself captivated by the eloquent speaker and was delighted to find a few months later that he and Johnson were going to be classmates in their first year at Divinity School. For the rest of Johnson’s life, the two were inseparable, excepting only the periods in which their careers forced them to live in different cities. Even then, they were devoted correspondents. Both men remained lifelong bachelors, confided in each other, and referred to one another by the classical references of “Damon” and “Pythias.” Even their friends commented on how strong their bond was; Edward Everett Hale wrote, “There existed for forty years an intimacy which could hardly have been understood by David and Jonathan.”8 For many gay people in the 1800s, the Biblical story of David and Jonathan, as well as the Greek and Roman classics, served as reference points to help them understand themselves and their relationships in a time when no other community or resources existed.9

Another friend and biographer, Joseph May, wrote of their relationship:

The confidential intercourse between Mr. Longfellow and Mr. Johnson discloses a perfect harmony, and the unrestricted but delicate intimacy of two rare and noble spirits. Letters, frequent and full, usually serious, often playful, always affectionate, passed between the pair… No experience was passed over unnoted, no emotion was unshared between these two friends. They found in each other something of that support and comfort which they were not seeking in the marriage state.10

When Samuel Johnson died in 1882, after a 40-year relationship, Samuel Longfellow appears to have spent the rest of his life serving as a mentor and fatherly figure to young gay men living in Cambridge, most notably William Morton Fullerton. Fullerton, openly attracted to men and women, first met Longfellow while he was attending Harvard. In 1888, while working for the Boston Record-Advertiser after graduation, Fullerton also began staying with Samuel in the Longfellow home on Brattle Street. Fullerton confirmed their close bond, writing to one of his many partners, “It is delightful to be here in the Craigie House study writing to you, my Marian. Mr. Longfellow sits near by reading.”11

Though the relationship was short-lived (Longfellow passed away just four years later), it was apparently an important one to both of them. They wrote and dedicated poetry to one another and sailed for Europe together on a grand tour. When Longfellow returned home the following year, Fullerton remained behind. The poet Oscar Fay Adams wrote that “The separation was keenly felt by Mr. Longfellow, though he said but little on the subject, and he was always hoping to see his young friend again.”12

When Longfellow died, he requested that his niece Alice Longfellow set aside the “books in the glass-book-case to be given to William Fullerton when he comes home.”13 Fullerton, in turn, composed an elegy for Longfellow, called Three Sonnets:

Yet gone he is, and I am left alone,

And pleasant places knowing him of yore

Seem strange without him for their charm is flown,

And yet they speak of him as not before.

Ah, this were better than the vague regret:

To know, to love, then loving to forget.14

Though he didn’t have the terminology to fully describe it, it’s clear that Longfellow’s same-sex relationships were an important part of his life. The affection he felt for the men in his life was, by his own admission, a true romantic love. He managed to pull together a small community of his own in a world where such a thing could not be found otherwise, and in turn positively shaped the lives of those around him.

Notes

Quotations from Samuel Longfellow's journals are from the volumes in the Reverend Samuel Longfellow (1819-1892) Papers (LONG 33705), Longfellow House-Washington’s Headquarters National Historic Site, cited below as RevSL Papers.

1. Joseph C. Abdo, The Quiet Radical (Lisbon, Portugal: Tenth Island Editions), 6.

2. Journal, Samuel Longfellow, February 24, 1837, RevSL Papers.

3. Journal, Samuel Longfellow, January 28-29, 1838, RevSL Papers.

4. Susan Ferentinos, Interpreting LGBT History at Museums and Historic Sites, pg. 36.

5. Journal, Samuel Longfellow, January 1, 1845, RevSL Papers.

6. Journal, Samuel Longfellow, January 12/13, 1845, RevSL Papers.

7. Journal, Samuel Longfellow, January 16, 1845, RevSL Papers.

8. Edward Everett Hale, Five Prophets of Today.

9. Graham Robb, Strangers: Homosexual Love in the Nineteenth Century (New York: W. W. Norton, 2005), 144, 239-240.

10. Joseph May, Memoir and Letters of Samuel Longfellow (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Col, 1894), 122-123.

11. Marion Mainwaring, Mysteries of Paris: The Quest for Morton Fullerton (Hanover, NH: University of New England Press, 2001), 42.

12. Oscar Fay Adams, "Samuel Longfellow," The New England Magazine 17 (1895): 212.

13. Abdo, 265. Will of Samuel Longfellow, copy in Series XI. Estate Records, in RevSL Papers.

14. William Morton Fullerton, "Three Sonnets," Scribner’s Magazine (March 1895).