Last updated: September 6, 2024

Article

A Glimpse into Historic Crow Life at Indiana Dunes

User: coreybirdman | iNaturalist.org | November 2022

Below is a passage from "The Dune Country," Reed's 1916 book that gives incomparable glimpses into what Indiana's sand dune region was like at the time. This particular excerpt highlights life habits of American crows (Corvus brachyrhynchos). His historic description paints a different picture of crows compared to today— whose populations have declined at Indiana Dunes. While crows are still seen in the park, stumbling upon thousands of them is no longer a common occurence. Crows in our region are still recovering from West Nile virus, introduced to the United States in 1999. Virtually all crows that come in contact with the virus die within a week, killing them at the highest rate compared to any other North American bird species.

Earl Howell Reed | Library of Congress

Dune Country: Chapter IV: The Crows

By: Earl Howell Reed

Of all the wild life along the dunes, the crow is the most active and conspicuous. He is ever present in the daytime, and his black form seems to be intimately associated with nearly every mass and contour in the landscape.

The artists and the poets can love him, but the hand of the prosaic and the philistine is against him. His enemies are numberless, and his life is one of constant combat and elusion. The owls seek him at night, and during the day he meets antagonism in many forms. Some ornithologists have tried to find justification for the crow, but the weight of the testimony is against him. He pilfers the eggs and nestlings of the songsters, invades the newly planted cornfields, and apparently abuses every confidence reposed in him.

He has been known to take his family into fields of sprouting potatoes and, when the plants were hardly out of the ground, feed its members on the soft tubers which were used as seed. Even very young chickens and ducks enter into his economies. He is an inveterate mischiefmaker, and by those who fail to see the attractive sides of his character, is looked upon as a general nuisance.

He cannot be considered valuable from a utilitarian point of view, but as a picturesque element he posses many charms. Notwithstanding the sins laid at his door, this bird is of absorbing interest. His genteel insolence, his ability to cope with the wiles of his persecutors, and his complete self-assurance may well challenge our admiration.

He takes full charge of the dune country before the morning sun appears above the horizon, and maintains his vigils until the evening shadows relieve him from further responsibility. All of the happenings on the sands, and among the pines, are subjected to his careful inspection and noisy comment. His curiosity is intense, and any unusual object or event will attract his excited scrutiny and an agitated assemblage of his friends.

Like many people, he is both wise and foolish to a surprising degree. He is crafty and circumspect in his methods of obtaining food and avoiding most of his enemies, but shows a lack of judgement when his curiosity is aroused.

He will approach quite near to a person sitting still, but will retreat in great trepidation at the slightest movement. An old crow knows the difference between a cane and a gun, but a man carrying a gun can ride a horse much nearer to him than he can go on foot.

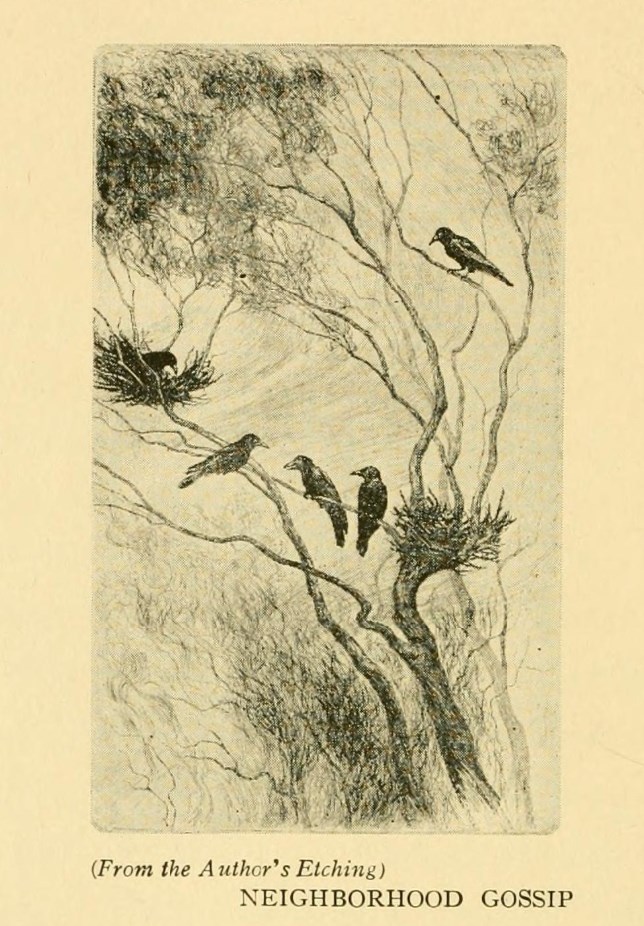

In the community life of the crows there is much material for study. Their social organization is cohesive and effective. It is impossible not to believe that they have a limited language. Different cries produce different effects among them. They undoubtedly communicate with each other. The older and wiser crows have qualities of leadership which compel or attract the obedience of the sable hordes that follow them in long processions through the air, and from the feeding grounds, and to the roosting-places at night.

The cries of the leaders are distinctive, and the entire band will wheel and change the direction of its flight when the loud signal comes from the head of the column. These bands often number several thousand birds.

Earl Howell Reed | Library of Congress

After spending the day in detached groups, they gather late in the afternoon, and prepare for the flight to the roosting grounds, which is an affair of the utmost importance and ceremony. A single scout will come ahead, and after slowly and carefully inspecting the area in the forest where the night is usually spent, he returns in the direction from which he came.

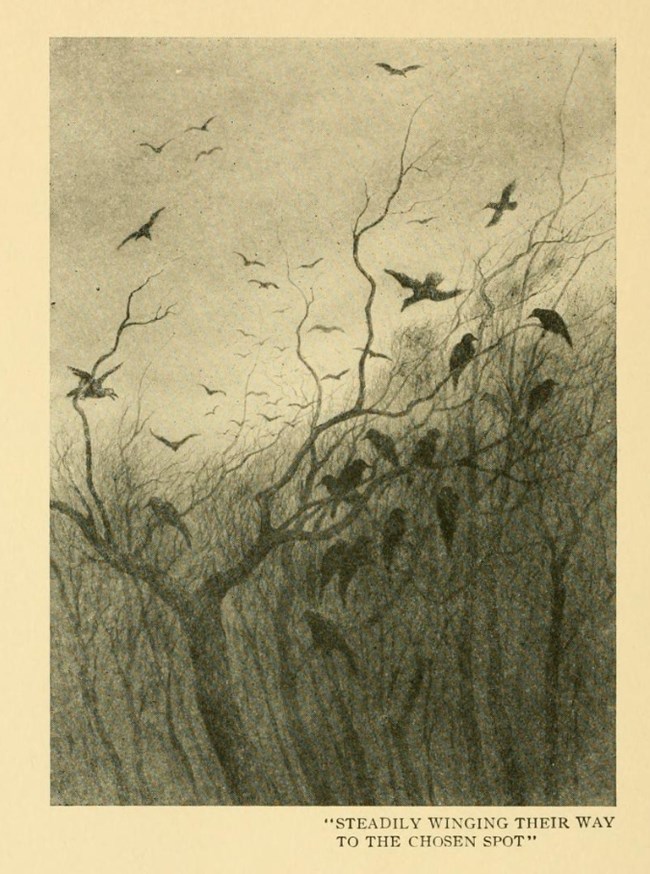

In a few minutes several crows come over the same course and apparently verify the conditions. These also return, and a little later, perhaps twenty or thirty more will appear and fly all over the territory under consideration. They go and report to the main body beyond the hills, and soon the horizon becomes black with the oncoming phalanxes, steadily winging their way to the chosen spot.

For a long time the sky above is filled with their dark forms, circling and hovering over and among the trees. Much uncertainty seems to agitate them, and there is a great deal of noisy confusion before even comparative quiet comes. It requires about half an hour for them to get comfortably settled after their arrival. Sentinels are posted and they maintain a vigilant watch during the night.

I have sat quietly on a log and seen these multitudes settle into the trees around me in the deep woods. Although perfectly motionless, I have sometimes been detected by a watchful sentinel. His quick, loud note of alarm arouses the entire aggregation, and the air is immediately filled with the turmoil of discordant cries and beating wings. Sacred precincts have been invaded, and an enemy is within the gates.

After much anxiety, and shifting of positions, confidence seems to finally be restored, and the black masses on the bending boughs become quiet.

A footfall on the dead leaves, the snapping of a twig, a suspicious movement among the trees, or the hoot of an owl, may alarm the wary watchers and start another uproar that will result in complete desertion of the vicinity of the suspected danger.

When morning comes, various groups visit the beach and strut along the shore, drinking and picking up stray morsels. Dead fish that have been cast in by the waves, and numerous insects crawling on the sand, are eagerly devoured. Usually before sunrise the crows have started out over the country in detached flocks.

Earl Howell Reed | Library of Congress

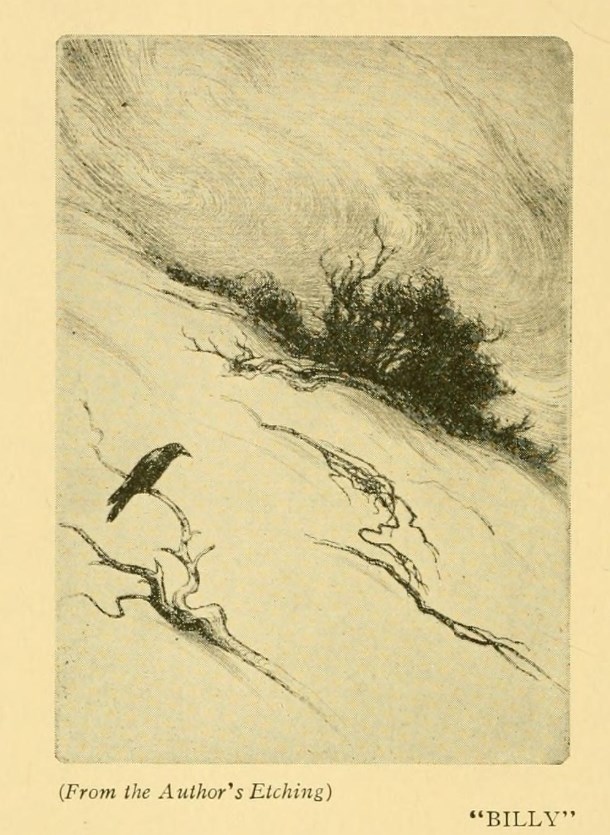

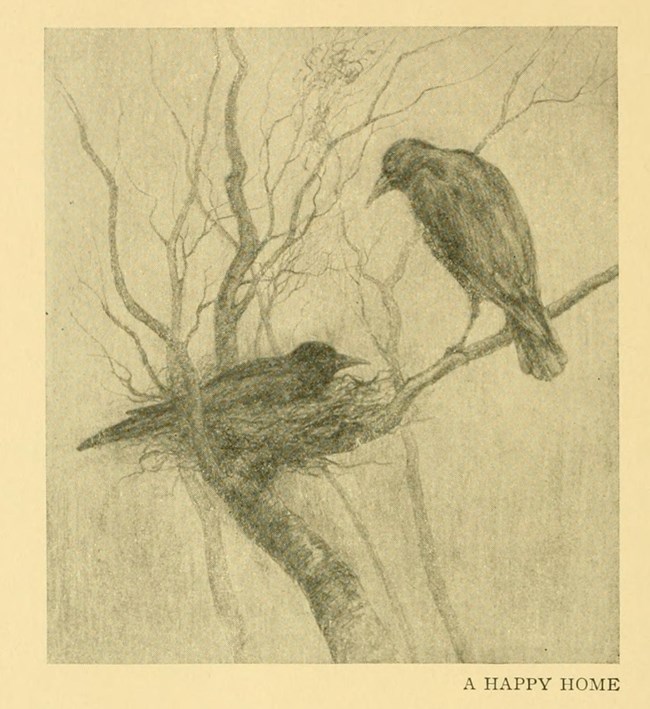

Some of the most pleasant memories of the dunes are clustered around "Billy," a pet crow which remained with us one summer though the kindness of a naturalist friend. He was acquired at a tender age, a small boy having abstracted him from a happy home in an old tree in the deep woods.

Earl Howell Reed | Library of Congress

His early life was devoted principally to bread and milk, hard boiled eggs, bits of meat, and other food, which he had to be constantly supplied. A large cage was built for his protection as well as for his confinement, until he could become domesticated and strong enough to take care of himself.

He became clamorous at unreasonable morning hours, and required constant attention during the day. His comical and whimsical ways soon found him a place in our affections, and Billy became a member of the family.

He developed a decided character of his own. When he was old enough to fly he was given his freedom, which he utilized in his own way. He would spend a large part of his time in a nearby ravine, studying the problems of crow life, but his visits to the house were frequent, and his demands insistent when he was hungry.

He would almost invariably discover the departure of any one of us who left the house, flying short distances ahead and waiting until he was overtaken, or proudly riding on our heads or shoulders, if he was not quite sure of the general direction of the expedition.

The berry patch was a great attraction time him, and if we took a basket with us he would help himself to the fruit after it had been picked, much preferring to have the picking done for him.

One of his delights was walking back and forth on the hammock. The loose meshes seemed to fascinate him, and he would spend much time in studying its intricacies and picking at the knots. He soon became distantly acquainted with Gip, our black cocker spaniel. While no particular intimacy developed between them, each seemed to understand that the other was a part of the family. They finally got to the point where they would eat out of the same dish.

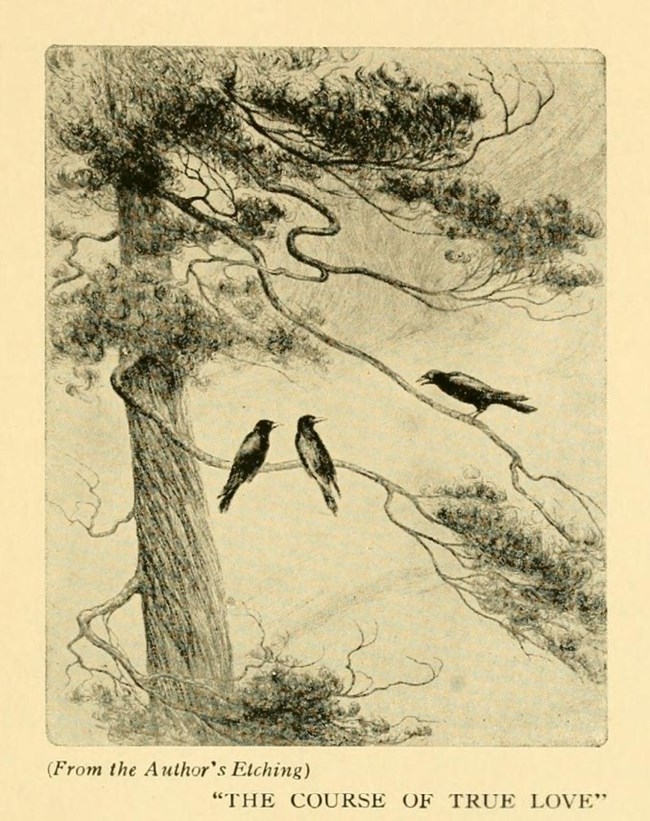

Billy was a delightful companion on many sketching trips into the dunes, and it was amusing to watch the perplexities of the wild crows when my close association with one of their own kind was observed. They could not understand the relationship, and it gave rise to much animated discussion. Billy was immediately visited when he flew into a tree top, and carefully looked over. Other crows joined in the consultations and the final verdict was not always favorable, for hostility frequently became evident, and poor Billy was compelled to leave the tree, often with cruel wounds. He was probably regarded as a heretic and a backslider, who had violated all crow traditions—a fit subject for ostracism and seclusion beyond the pale.

He promptly responded to my call when he got in trouble, or thought it might be lunch-time. He would watch with much interest the undoing of the sandwhiches, and would wait expectantly on my knee for the coveted tid-bits which constituted his share of the meal.

When preparations were made for the return, Billy's interest in the day's proceedings seemed to flag, and he would suddenly disappear, not to be seen again until the next morning, when he would alight on the rail of the back porch and loudly demand his breakfast.

I was never able to ascertain where he spent a great part of his time. His identity was, of course, lost when he was with other crows . . . and we only knew him when he was with us.

He had the elemental love of color, which always begins with red, and the vermillion on my pallete seemed to exercise a spell over him. After getting his bill into it, he would plume and pick his feathers, and I have spent considerable time with a rag and benzine in trying to make him presentable after he had produced quite good post-impressionistic pictures on the feathers of his breast.

Occasionally he would take my pencils or brushes into the trees while I was at work, and play with them for some time, but he would not return anything that he had once secured. I often had difficulty in recovering lost articles, but usually he would accidentally drop them. In such cases there would be a race between us, for he quickly became jealous of their possession.

Billy was, to a certain extent, affectionate, and would often come to be petted, alighting on my outstretched hand and holding his head down toward me. When his head feathers were stroked gently, low, contented sounds indicate the pleasure he took in the attention devoted to him.

Stories of the numerous little tricks and insinuating ways of this interesting bird could occupy many pages, but enough has been told to convey an idea of his character. Perhaps he may have been a rascal at heart, but his ancestry was responsible for his moral shortcomings.

One morning we missed Billy, and we possibly have never seen him since. He may have answered "the call of the wild" and joined the black company that goes over into the back country in the mornings and returns to the bluffs at night, or he may have fallen a victim to indiscriminating over-confidence in mankind—a misfortune that is not confined to crows.

He left tender recollections with us. He had an engaging personality, and was a most admirable and lovable crow. Such an epitaph would be due him if he has departed from life, and a more sincere tribute could not be offered to him if he still lives.

During the following year I was able to approach quite near to a crow who seemed to show slight signs of recognition. A broken pinion in his left wing, a reminiscence of a vicious battle in the fall, seemed to complete the identification of Billy. He appeared to be making his headquarters in the ravine. Further careful observation and investigation convinced me that if this crow was actually Billy, he had laid three eggs.

Earl Howell Reed | Library of Congress

It was a contented couple whose nest was in the gnarled branches in the ravine, where the little home was protected from the chill spring winds. In due time small, queer-looking heads appeared above the edge of the nest, with widely opened bills that clamored continuously for the bits of food which the assiduous parents had to supply constantly. The nest required much attention. Marauding red squirrels, owls, hawks, and other enemies had to be kept away from the time the first egg was laid until the fledglings were old enough to fly. Their first attempts resulted in many falls, but they soon became experts, and one morning the entire family was gone.

They probably flew over into the back country, where food was more abundant and where they were subjected to less observation.

The nest was never used again. The twigs, little pieces of wild grapevine, and moss of which it was made, have gradually fallen away during the succeeding years, until but a few fragments remain in the tree crotch. A red lead pencil was found under the tree. Possibly "Billie" may have tucked it in among the twigs as a souvenir of former ties, or its color may have suggested esthetic adornment of a happy home.