Part of a series of articles titled Park Paleontology News - Vol. 16, No. 1, Spring 2024.

Article

A Georgia State University and National Park Service Collaboration: Fossil Fact Sheets in the Southeast Region

Georgia State University

for Park Paleontology Newsletter, Spring 2024

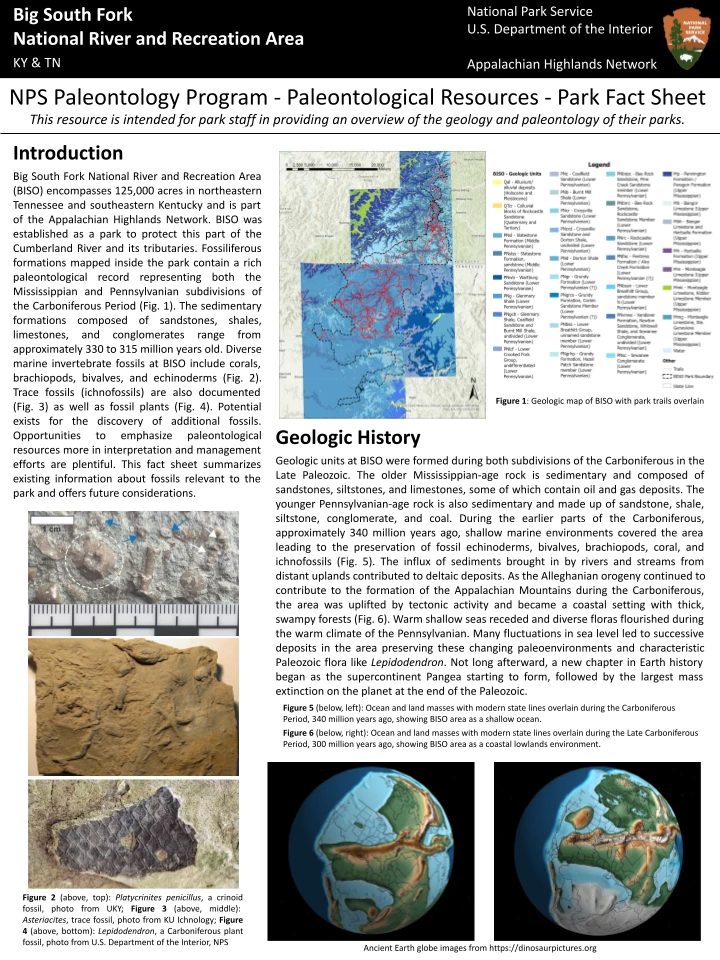

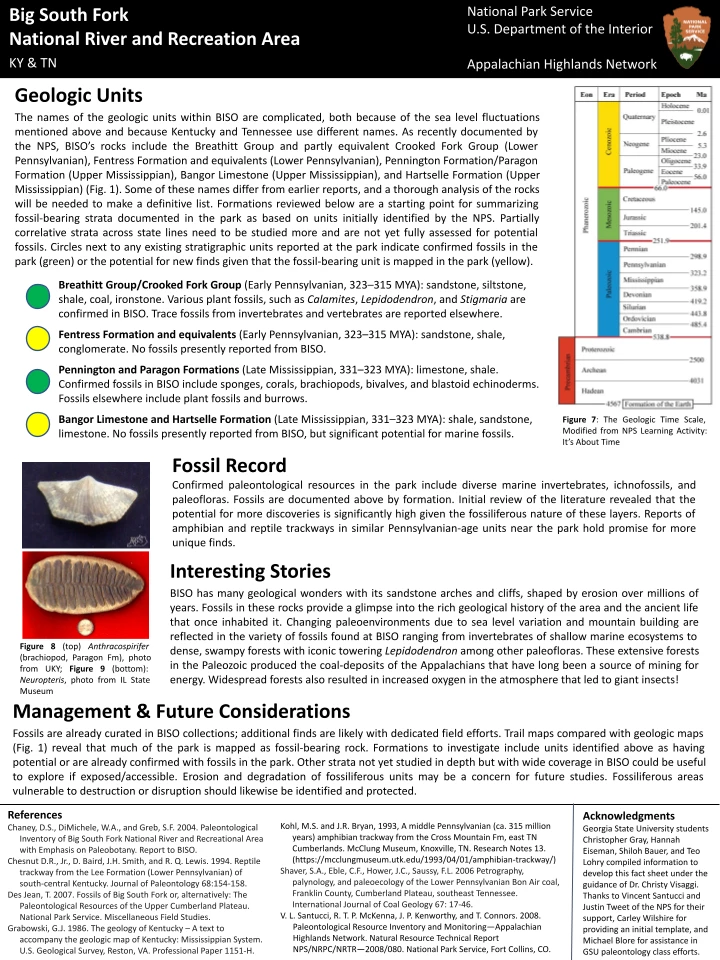

To address this gap and bring attention to NPS fossils in the Southeast Region, Dr. Christy Visaggi and students in the Fall 2023 Principles of Paleontology course at Georgia State University (GSU) collaborated with the NPS on a new project. The goals of the collaboration included confirming and synthesizing what had already been documented in a subset of parks as well as exploring the potential for new discoveries. The pilot collaboration began in August 2023 and involved 18 undergraduate and graduate students enrolled in the paleontology course at GSU. Through discussions with the NPS, six parks in the region were identified as promising to study for their paleontological resources. This project was designed with the purpose of working alongside the NPS to first examine existing data and literature on fossils in and around these parks. This step included identifying geologic units reported as fossiliferous in or near the parks and considering where new discoveries might be made by comparing available maps. Then, in order to create a pool of knowledge that could be useful for park rangers and other staff to have in learning more about fossils in and around their parks, groups of students developed a series of “Fossil Fact Sheets” that summarized key details about the geology, geologic history, and paleontological resources of these parks. Topics additionally considered by the students included the management and preservation of inventoried and potential fossils given their scientific value, as well as interesting stories that could be useful for connecting and communicating such scientific stories to the general public. In turn, the students learned about natural resource management in the NPS, giving them a head start in understanding this field should they want to pursue a career in it. The NPS research also provided real-world experience and application of what they were learning in class with meaningful results for the NPS and the public. Finally, teams of students had the chance to present preliminary findings at the on-campus GSU STEM conference in November 2023 (Figure 1). Several of the lead students for these posters are now preparing to share their work at the southeastern section meeting of the Geological Society of America in April 2024.

The six parks selected for study were Big South Fork National River and Recreation Area (BISO), Chickamauga & Chattanooga National Military Park (CHCH), Cumberland Gap National Historical Park (CUGA), Little River Canyon National Preserve (LIRI), Russell Cave National Monument (RUCA), and Obed Wild and Scenic River (OBED). These parks were chosen because geologic units known to have fossils are mapped in the vicinity of the park and/or paleontological resources are already known at the park with the potential for more upon further exploration. The GSU project model began by asking students if they had any preferences related to these six parks concerning what they might like to study for their class research project. Some indicated an interest in studying parks that had caves or water resources or parks from a particular state or location in the Southeast Region. Teams were then formed based on preferences, including if students wanted the NPS research to be their main class project or if they preferred to study fossil shells in the lab first and then have the parks be a secondary focus. Ultimately, six groups of three students were assigned to specific parks and additionally supported by an undergraduate senior research student in Dr. Visaggi’s lab. Team leads or co-leads were selected for each park based on whether students had an interest in leadership for the class research project or if they were graduate students in the course.

To foster collaboration among students, and to support studying similar stratigraphic units across adjacent parks, it was decided to pair parks as part of summarizing and presenting the research. Two parks from the Appalachian Highlands Inventory & Monitoring (I&M) Network (BISO & OBED) formed a group representing rocks of similar geologic history from Tennessee and Kentucky. Then the four parks of interest in the Cumberland Piedmont I&M Network were first grouped by stratigraphically similar locations near each other in Alabama (RUCA & LIRI), followed by the remaining pair of parks covering parts of Georgia, Tennessee, Kentucky, and Virginia (CHCH & CUGA).

While all of these parks have fossil-bearing units predominantly from the Paleozoic Era (541 to 252 mya), a variety of periods, paleoenvironments, and fossils are represented. For example, BISO and OBED in the Appalachian Highlands I&M Network have strata from the Carboniferous Period (359 to 299 mya). Paleontological resources at BISO encompass a wide variety of fossil plants (e.g., Calamites, Neuropteris), marine invertebrates (e.g., brachiopods, echinoderms), and different kinds of invertebrate ichnofossils. Very few fossils are noted from OBED as based on anecdotal reports, but the underlying lithology of shale, sandstone, and other fossiliferous strata are similar to BISO indicating the potential for additional paleontological discoveries.

NPS photo.

All of this information and more was compiled by the GSU students into a Fossil Fact Sheet for each park as part of their final project. These draft educational resources, currently in revision, are intended to serve as quick summaries of geological and paleontological information for these parks. Data included in the fact sheets incorporate geologic history, stratigraphic formations at the park, confirmed and potential fossil discoveries, management considerations, and interesting stories for interpretation. The Fossil Fact Sheets were designed with the intention to give park staff easy-to-digest knowledge about the prehistoric wonders of their park that they may not have yet fully recognized, and which could serve as a jumping-off point for future research, surveys, interpretive programming, and management of these resources (Figures 3 & 4).

The project was announced in class to mixed reception among the students: some were excited for the opportunity to work with the NPS and to dip their toes into the world of paleontological research, while others were more hesitant. It was a much different kind of work than what many students were used to doing in class. As the lead author of this article and a student who participated in the experience, because I’ve always been very interested in paleontology, I was excited to see what this project could reveal to me about what pursuing a job like this might look like outside of school. I was right to be excited as this type of research was completely new to me, but I found that I enjoyed it, even though the park I studied (OBED) was one of the parks that had less recorded information for both confirmed and potential fossils. This project helped stretch academic muscles that I hadn’t used properly in a while, such as reviewing and understanding scientific literature; collecting, analyzing, and condensing large amounts of existing information; and learning how to manage and lead a team. In the end, many students appreciated being able to learn paleontology by doing, with practical applications that included perspectives about natural resource management, rarely the focus of paleontology courses. To have such a meaningful experience as part of the coursework at GSU was extremely rewarding; we hope to have a chance to contribute further to NPS paleontology by participating in future field efforts.

Related Links

-

Big South Fork National River and Recreation Area (BISO), Kentucky and Tennessee—[BISO Geodiversity Atlas] [BISO Park Home] [BISO npshistory.com]

-

Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park (CHCH), Georgia—[CHCH Geodiversity Atlas] [CHCH Park Home] [CHCH npshistory.com]

-

Cumberland Island National Seashore (CUIS), Georgia—[CUIS Geodiversity Atlas] [CUIS Park Home] [CUIS npshistory.com]

-

Little River Canyon National Preserve (LIRI), Alabama—[LIRI Geodiversity Atlas] [LIRI Park Home] [LIRI npshistory.com]

-

Russell Cave National Monument (RUCA), Alabama—[RUCA Geodiversity Atlas] [RUCA Park Home] [RUCA npshistory.com]

-

Obed Wild and Scenic River (OBED), Tennessee—[OBED Geodiversity Atlas] [OBED Park Home] [OBED npshistory.com]

Last updated: April 4, 2024