Last updated: April 4, 2025

Article

A Disability Christmas Carol

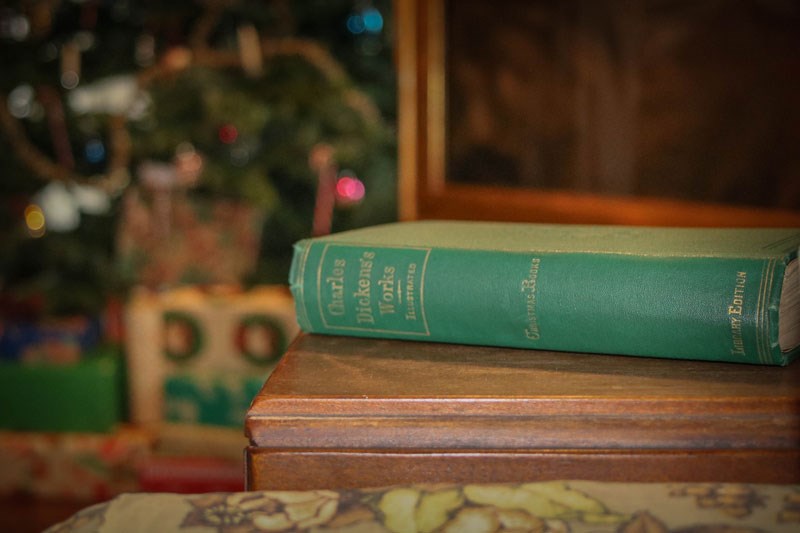

FDR’s volume of Christmas Works by Charles Dickens (HOFR 3646), featuring “A Christmas Carol.”

Preface

Each year during the Christmas season, two icons of disability come together for a Roosevelt family holiday tradition.

While recently exploring the book collections in FDR’s home, we discovered one volume in a curious condition. Of all the handsomely bound volumes lining the walls of President Roosevelt’s living room, one stood out among the complete set of novels and stories by the celebrated British author Charles Dickens. Unlike the others contained in this collection, this volume, entitled Christmas Works, shows signs of much wear and use—the binding broken, pages detaching, and significant wear on the edges. Included in this volume is Dickens’ enduring holiday classic, A Christmas Carol, its physical condition evidence that this story alone, was read again and again. Typically, a book in such condition would be subject to conservation, tightening the binding, reattaching loosened pages, and cleaning the surfaces from agents of deterioration for its continued preservation. Yet here we are faced with a dilemma—do we preserve the object itself or do we preserve its wear and use. In drawing attention to the observable evidence of FDR reading this particular volume and this particular story every Christmas, we have endeavored to rise the Ghost of an Idea, which shall not put our readers out of humour with themselves, with each other, with the season, or with us. May it haunt your web browser or smart phone pleasantly, and no one wish to lay it.

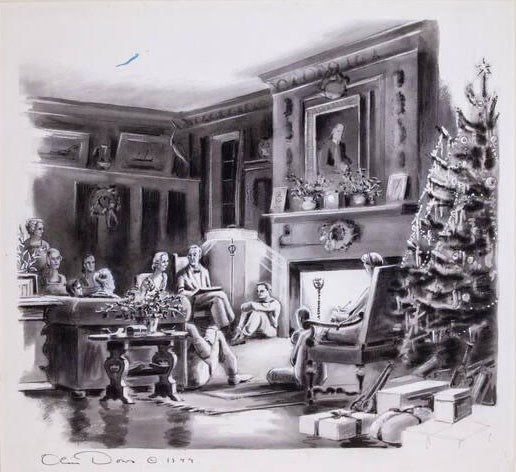

Olin Dows’ illustration of FDR reading A Christmas Carol at Hyde Park. The artist, a family friend, included this drawing in his book “Franklin Roosevelt at Hyde Park,” published in 1949. Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library.

Stave One

“A Christmas rite for me is always to re-read that immortal little story by Charles Dickens, ‘A Christmas Carol.’”

Franklin D. Roosevelt

“The reading of this tale has so long been a ritual in our family that Christmas would not seem the same unless it began with the story of old Scrooge and how he learned about the spirit of Christmas!”

Eleanor Roosevelt

On Dec. 24, 1937, in a White House decked with holly, mistletoe and a white-trimmed spruce, President Franklin D. Roosevelt — as was his annual custom — read A Christmas Carol aloud to his family. His son James remembered sitting still and listening, wide-eyed, to his father’s clear, confident voice . . . soaring into the higher registers for . . . Tiny Tim, then shifting into a snarly imitation of mean old Scrooge. He was so famous for his renditions that The Times once suggested it should become a radio broadcast. FDR adopted the custom from his years as a schoolboy at Groton, where Headmaster Endicott Peabody would read the story to his pupils each Christmas season. (A recording of Peabody reading a selection from A Christmas Carol is available on YouTube.) Rather than complete Dickens’ novella in a single sitting, FDR might read selections over the days immediately leading to Christmas. In the passage of time, ER noticed FDR would skip over pages and concentrate on his favorite passages. In our time, the scene is often recreated to the delight of visitors touring the Home of FDR during the holidays. This Roosevelt holiday tradition brings together two icons of disability. Scholars have explored the meaning and representation of both FDR’s and Tiny Tim’s disability, but we are not aware that anyone has yet considered the two of them together.

Recording of "A Christmas Carol" read by Endicott Peabody, ca. 1922. From the FDR's record collection (HOFR 2334).

Published in December 1843, A Christmas Carol became an instant bestseller. The initial printing of 6,000 copies sold out on Christmas Eve. The following year, eleven more editions were released, and it has remained in publication since. It was Dickens’ most popular book in the United States. Followed by countless print, stage, and screen productions, reading or watching it became a sacred ritual for many.

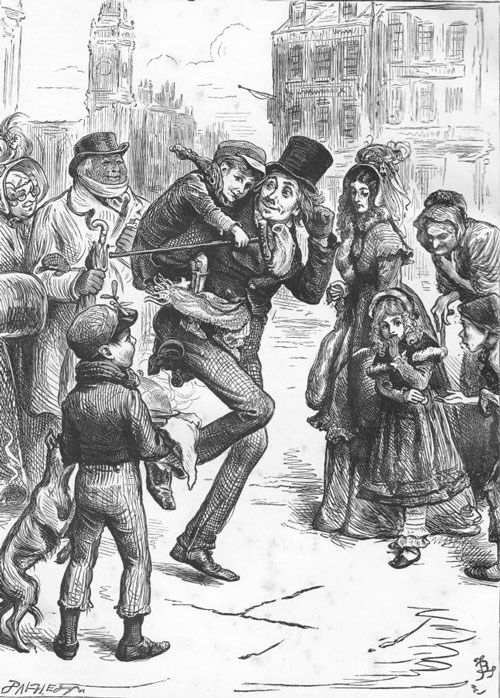

Illustration of Bob Cratchit and Tiny Tim from an early edition of "A Christmas Carol," featuring Tim’s signature crutch and even his leg braces.

Stave Two

“Alas for Tiny Tim, he bore a little crutch, and had his limbs supported by an iron frame!”

Appearing every year in December, Tiny Tim is one of the most recognizable characters in Victorian literature and enduring symbols of the Christmas season. Dickens does not address why Tiny Tim wears “an iron frame” and uses a crutch, nor is he clear how the young boy will die if Scrooge doesn't change his ways.

Historians and medical professionals speculate on the nature of Tiny Tim’s illness, some suggesting that he had cerebral palsy, rickets, tuberculosis, and even polio. The first published medical description of a paralytic disease resembling polio appeared in 1789 in London. Transformation of polio into an epidemic occurred only in large urban centers of Europe and North America following the Industrial Revolution. Polio is not likely the appropriate diagnosis for Tiny Tim because, as historians have pointed out, it was thought incurable. More likely, Tiny Tim's cramped life in a polluted London would have put him at risk for both rickets and tuberculosis. In Dickens’ time, the number of children in working-class London families diagnosed with rickets reached 60 percent. We will never really know what caused Tiny Tim’s disability. It is likely that the character was based on two real people in Dickens' life—a nephew who died of tuberculosis, and the son of a friend who was disabled. The image of Tiny Tim’s crutch and iron frame certainly loomed large in FDR’s imagination and in all probability, fostered an affection just as he had for his fellow patients at Warm Springs.

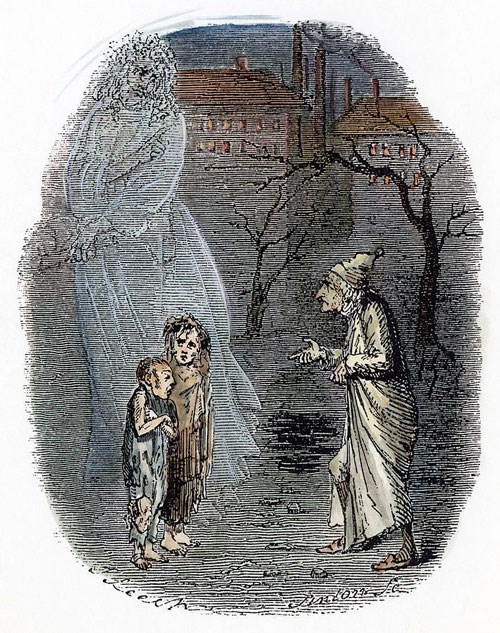

"Ignorance and Want," etching by John Leech for the 1843 edition of "A Christmas Carol."

Stave Three

“At this festive season of the year, Mr. Scrooge, it is more than usually desirable that we should make some slight provision for the poor and destitute.”

A Christmas Carol

“We look on the money raised by the March of Dimes as a trust fund, to bring back health, strength and usefulness to those stricken by polio.”

Basil O’Connor, President, National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis

A Christmas Carol was a product of its time. Initially intended to be a pamphlet called “An Appeal to the People of England on behalf of the Poor Man’s Child,” it very soon became a story populated with now well-known characters that embody a tale of charity. Dickens was moved by a report on child labor in the UK that left him “stricken.” The report included testimony of children who worked 11 to 16 hours six days a week, many in appalling conditions. The brutality was a result of the industrial revolution and rise of cottage industries. Workers, especially children, were dehumanized as commodities.

A widespread belief that the poor tended to be so because they were lazy, compounded the social problem. Charity was thought by some to encourage laziness. Thus, if they were to receive help, it should be under conditions so awful to discourage acceptance. A grim but popular perspective proposed that hunger would correct an untenable population. Dickens references these sentiments with a key setup in A Christmas Carol:

“At this festive season of the year, Mr. Scrooge,” said the gentleman, taking up a pen, “it is more than usually desirable that we should make some slight provision for the poor and destitute, who suffer greatly at the present time. Many thousands are in want of common necessaries; hundreds of thousands are in want of common comforts, sir.”

“Are there no prisons?” asked Scrooge.

“Plenty of prisons,” said the gentleman, laying down the pen again.

“And the Union workhouses?” demanded Scrooge. “Are they still in operation?”

“The are. Still,” returned the gentleman, “I wish I could say they were not.”

“Oh! I was afraid, from what you said at first, that something had occurred to stop them in their useful course,” said Scrooge. “I’m very glad to hear it. . . . “I help to support the establishments I have mentioned: they cost enough: and those who are badly off must go there.”

“Many can’t go there; and many would rather die.”

“If they would rather die,” said Scrooge, “they had better do it, and decrease the surplus population.”

Social philosophers like Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx proposed social systems of welfare. Even a generation earlier, Thomas Paine argued for tax credits to help raise children, old age pensions, and national disability insurance. But Dickens was not a socialist. He espoused a system in which employers were responsible for the well-being of their employees.

Still, A Christmas Carol embraces the responsibility of employers AND charity. Scrooge astonishes Bob Cratchit when he returns to work late, the day after Christmas. “Now, I tell you what, my friend,” said Scrooge, “I am not going to stand this sort of thing any longer.” Leaping from his desk, Scrooge declares:

“A merry Christmas, Bob!” said Scrooge. . . . “A merrier Christmas, Bob, my good fellow, than I have given you, for many a year! I’ll raise your salary, and endeavour to assist your struggling family, and we will discuss your affairs this very afternoon.”

We learn that “Scrooge was better than his work. He did it all, and infinitely more; and to Tiny Tim, who did NOT die, he was a second father.”

Dickens portrays Tiny Tim as weak and sickly, and often carried by his father, to elicit sympathy and ultimately transform Scrooge from an indifferent miser to a responsible, generous employer and philanthropist. In turn, the enormous success of A Christmas Carol did much to popularize the holiday and establish the concept of Christmas charity.

Poster for The President Hotel's birthday ball to raise funds in support of the fight to cure infantile paralysis, 1939. Library of Congress.

“Who would have thought a generation ago . . . that the needy, the blind and the crippled children would receive some measure of protection which will reach down to the millions of Bob Cratchit's, the Marthas and the Tiny Tims.”

Franklin D. Roosevelt

1939 Christmas Radio Address to the Nation

When Warm Springs faced a financial crisis in 1934, FDR allowed his birthday (January 30) to become the focus of a national fundraising campaign. The resulting President’s Birthday Balls held in venues across the country, raised over one million dollars, far exceeding the goal of $100,000. The success was in large part due to an innovative fundraising tactic, relying on tens of thousands of small contributions rather than targeted large donations—a hallmark of the subsequent March of Dimes campaign. As the most influential health charity of its time, the March of Dimes became a model of philanthropy. With its focus on single donations of “only a dime,” those with modest income could contribute and more people could participate.

However, Roosevelt’s ideal was far more complex. The National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis promoted itself not merely a charity, but a national insurance policy supported by the American people. A national health insurance program was one of FDR’s original but unrealized goals for the New Deal and the Social Security Act. Earlier in his political career, Roosevelt identified the necessity of private charity, employer responsibility, and government intervention in the health and economic welfare of its citizens. In a 1927 address to the National Society for Crippled Children of the United States of America, he said:

This thought of state responsibility I am perfectly convinced is sound, not only economically, but constitutionally. . . . Today a large part of the work is being conducted, I believe, by private organizations. It is being carried on by private gifts. That must not stop, but at the same time, we, as citizens of our several states, have the right to go to the law-makers and to the executives of our state, and insist that the state fails to perform one of its functions of government, if it fails to aid in this kind of work.

Frederick Barnard’s (1846-1896) illustration of Bob Cratchit and Tiny Tim from an early edition of "A Christmas Carol" (left). 1939 March of Dimes Poster (right).

Stave Four

“His active little crutch was heard upon the floor, and back came Tiny Tim before another word was spoken, escorted by his brother and sister to his stool before the fire.”

Portrayals in literature and popular culture, like Tiny Tim, shape and potentially misguide our understanding of disability. While the work of both Dickens and Roosevelt inspired many to be generous, the means to achieve those ends were not without flaw. The sweet innocent—that is, the helpless disabled person with a heart of gold—is among the prevailing caricatures of disabled people in story and film. These characters, of which Tiny Tim is a definitive example, inspire pity to motivate generosity. Although Dickens’ stories habitually employ children in highly sentimental ways—poor, alone, and abused if not “crippled”—disability scholars review Tiny Tim with much criticism for this characterization. But characters such as Tiny Tim often provide little to no development in the story, nor do they have a future; their primary purpose is to be disabled, inspire sympathy, and ultimately encourage the generosity of others. Inherent in these caricatures is the belief that the disabled person can be cured through charity. Tiny Tim sees himself as a reminder of Christ’s healings, suggesting there is hope for a cure of his disability:

"Somehow he gets thoughtful, sitting by himself so much, and thinks the strangest things you ever heard. He told me, coming home, that he hoped the people saw him in the church, because he was a cripple, and it might be pleasant to them to remember upon Christmas Day, who made lame beggars walk, and blind men see."

Roosevelt’s extensive fundraising efforts also employed the sweet innocent. The March of Dimes advertising campaigns usually include images of polio survivors, often children, on crutches or in wheelchairs to invoke popular sympathy. While Roosevelt is admired for bringing public recognition to polio and a cure, many scholars now categorize these images as harmful, arousing fearful stigma.

Scrooge’s belief that charity should only be given under conditions so awful represents Western ideals of independence, that is, one should strive to take care of themselves rather than accept charity. While the work of FDR and Dickens inspire a softer approach, it is important to recognize the imagery they create in pursuit of charitable giving promotes assumptions that disability is so awful, no one would choose to remain in such condition. Disability scholars argue that such characterizations lead nondisabled people to believe people with disabilities are often a helpless burden. It is a harmful representation that not only may encourage us to regard disabled people with fear and pity but is distasteful to the millions of people who live with a disability.

Objectifying people with disabilities in this way, assumes they are incapable of being anything other than disabled. Even FDR was subject to such characterization. In a letter sent from FDR’s home in 1921, family friend Lily Norton wrote to a friend,

tragedy rather overshadows this once so happy & prosperous family, for Mrs. R’s only son, Franklin Roosevelt, was struck down in August with a terribly serious case of infantile paralysis. . . . He’s had a brilliant career as assistant of the Navy . . . & then a few brief weeks of crowded glory & excitement when nominated by the Democrats for the Vice Presidency. Now he is a cripple—will he ever be anything else?”

Scrooge and the Ghost of Christmas Present, from the first edition of “A Christmas Carol.” Engraving by John Leech.

Stave Five

“The shadows of the things that would have been, may be dispelled.”

Unlike Dickens’ final stave, this is NOT the end of it for our story. If you follow our work, you know that at the Home of Franklin D. Roosevelt National Historic Site, we are reevaluating the way FDR’s disability has been interpreted and represented. At the same time, the National Park Service is highlighting disability stories throughout the NPS system and adding disability perspectives to the World War II Homefront theme study.

Most Americans today and in FDR’s lifetime knew he had polio and experienced paralysis to some extent. Despite this relatively common knowledge, many stories of FDR and his disability are less than accurate and often sentimental. Common narratives are that he hid his disability from the American public and that he “overcame” his disability. For us, it is important to dispel portrayals that do not align with the evidence we are finding. We choose to adopt more subtle interpretations that embrace the nuances we observe in his life and story. We feel that FDR did not deceive the public, hiding his disability, but that he and others “managed” his public appearance, possibly with a range of differing motives. The access to wealth that enabled FDR to manage his disability is also central to revisionist critiques of his experience as a polio survivor, an unattainable circumstance for most. However, Roosevelt did not only use his wealth for personal benefit alone. Roosevelt’s activism and his massive fundraising efforts for polio research helped pioneer the fields of orthopedics and rehabilitative medicine. The Georgia Warm Springs Foundation, the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, and the March of Dimes, all established by Roosevelt, made polio research and the discovery of a vaccine possible.

Many have studied FDR and Tiny Tim as disability icons, but to our knowledge, the possible connections between the two narratives are not fully explored. While we can never know if FDR felt some kinship to Tiny Tim, we do know he shared a spirit or two with A Christmas Carol. We can also say that his life proved to contradict the portrayal of the disabled in Dickens’ story.

Just as Scrooge transforms in A Christmas Carol, so too did FDR transform his relationship to disability over time, and so too will we continue to transform how we understand and talk about FDR’s legacy in relation to disability.

Frank Futral and Shelby Landmark, PhD

Frank is the Curator at Roosevelt & Vanderbilt National Historic Sites. Shelby is the Mellon Fellow for Disability Representation at Historic Sites at the Home of Franklin D. Roosevelt National Historic Site.

Works Consulted

Broich, J. (2021). “The real reason Charles Dickens wrote A Christmas Carol,” Time. A Christmas Carol: The True History Behind the Dickens Story | TIME

Dorfman, R. G., Orkaby, A., & Desai, S. P. (2018). “Dr Polio: Revisiting FDR’s medical legacy.” Canadian Journal of Health History, 35(1), 160-192.

Norden, M. F. (2003). “Tiny Tim on screen: A disability studies perspective.” In J. Glavin (ed.), Dickens on Screen, Cambridge University Press, 188-198.

Norden, M. F. (1994). The cinema of isolation: A history of physical disability in the movies. Rutgers University Press.

Rodas, J. M. (2004). “Tiny Tim, Blind Bertha, and the resistance of Miss Mowcher: Charles Dickens and the uses of disability.” In Dickens Studies Annual, 34, 51-97. Penn State University Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44372091

Roosevelt, F. D. (1927). Why bother with the crippled child? [Speech]. Disability History Museum (W1 CR201). disability history museum--"Why Bother With The Crippled Child?" (disabilitymuseum.org)

Roosevelt, F. D. (1939). Radio Christmas Greeting to the Nation, December 24, 1939.

Ward, G. C. (1989). A first-class temperament: The emergence of Franklin Roosevelt 1905-1928. Vintage Books.

Tags

- home of franklin d roosevelt national historic site

- fdr

- presidents

- franklin d. roosevelt

- disability history

- christmas

- disability awareness

- disability

- disability history early attitudes

- disability history shifting attitudes

- disability history presidents

- charles dickens

- mellon humanities fellowship

- literature

- novel