Last updated: September 3, 2025

Article

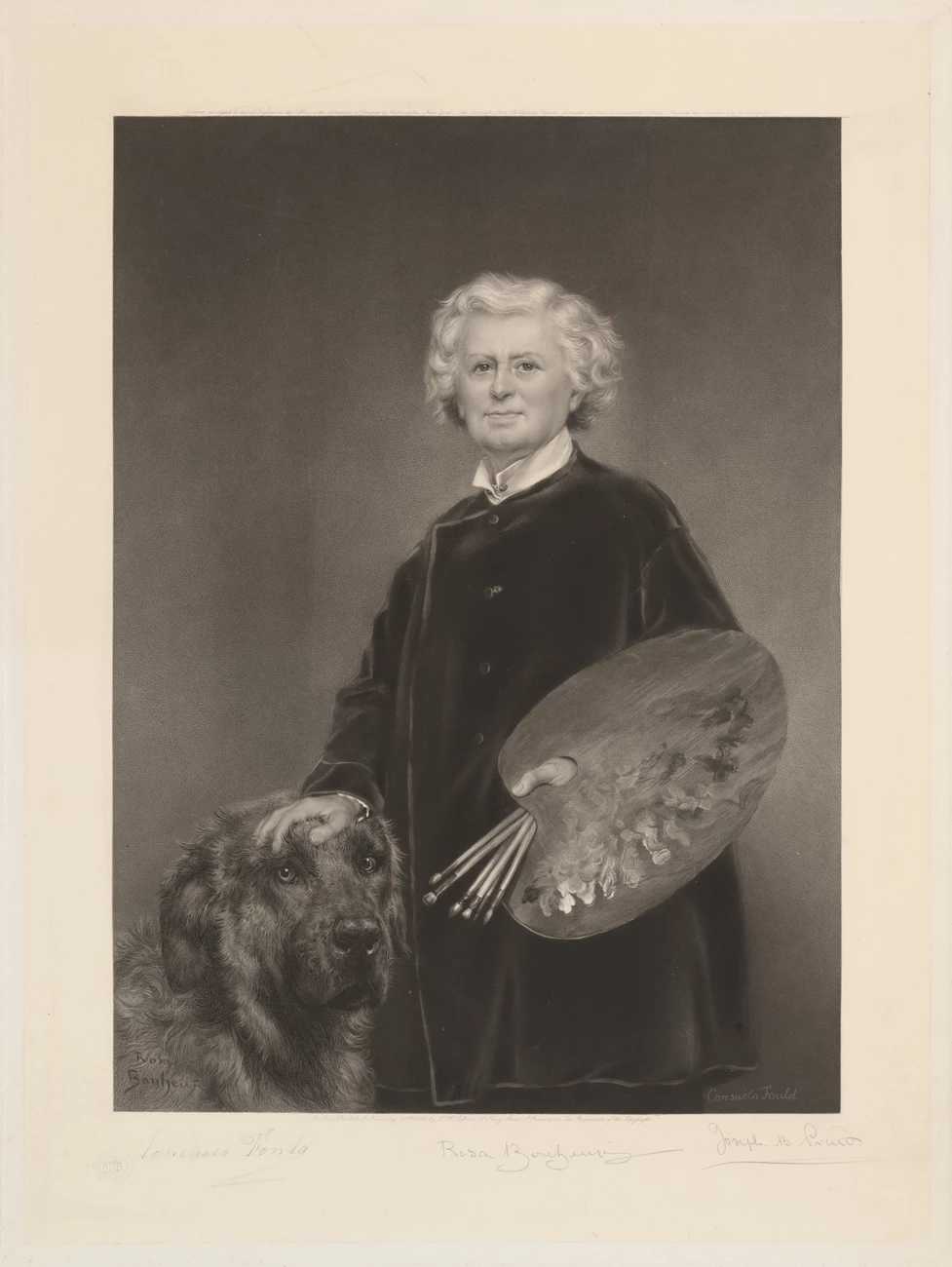

A Collector’s Passion for the Art of Rosa Bonheur

The Bonheur bug bit Frederick Billings. In the early 1860s, while travelling in Europe to buy arms for the Union Army, Billings fell in love with the works of several European artists. Among his favorites was French artist Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899). In 1871, he bought an engraving of her work The Horse Fair and proudly displayed it in his mansion. He also purchased an engraving of Rosa Bonheur with a Steer (also known as Portrait of Rosa Bonheur), artist Edouard Louis Dubufe’s depiction of Bonheur (and a bovine buddy). Just who was this woman, and why did her work have such a hold on Billings?

Engraved by Joseph Bishop Pratt after a painting by Consuelo Fould.

The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1980

Object Number: 1980.1093

Public domain. Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Cornelius Vanderbilt, 1887 (Accession Number: 87.25)

Public domain. Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Rosa Bonheur (French, 1822–1899)

Black chalk, with gray wash and white highlights, on buff paper

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Mr. and Mrs. Claus von Bülow Gift, 1975 (1975.319.2). Public domain.

Rosa Bonheur and Édouard Louis Dubufe (French, 1819–1883)

Oil on canvas

Collection of the Palace of Versailles, France. Public domain.

NPS Photo/Dispenzirie

Today, visitors to Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller National Historical Park can once again bear witness to “the great animal paintings” and the portrait of the intrepid woman who made them.

For information on seeing Bonheur's work in person, or general information tours and programs at Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller National Historical Park, visit Ranger-Led Programs.