Last updated: January 23, 2021

Article

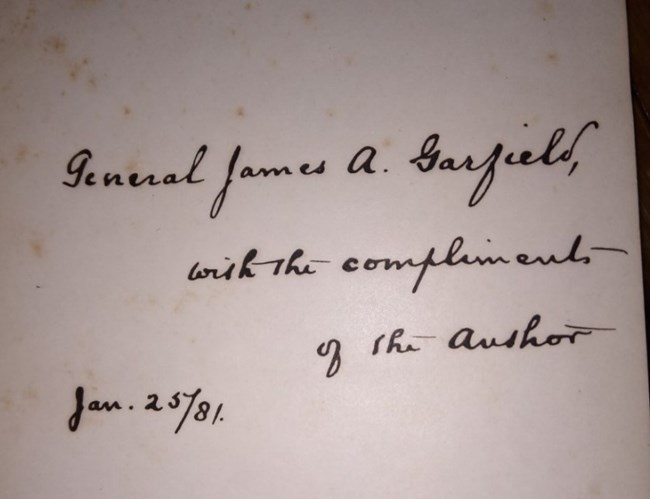

A Century of Dishonor by Helen Hunt Jackson

NPS

Helen Hunt Jackson shares a connection to First Lady Lucretia Garfield by way of her acquaintance with Emily Dickinson. Dickinson, the famed American poet, was fifth cousin to Lucretia, and a childhood friend of Helen Hunt Jackson. Jackson and Dickinson both pursued fictional writing and conferred with one another, sharing notes and ideas frequently. In 1879, however, Jackson attended a lecture in Boston and heard Ponca Chief Standing Bear describe the process by which his tribe was expelled from their ancestral lands. Standing Bear’s lecture struck a nerve with Jackson and she immediately and tirelessly began to research federal policy, visit Indian tribes, and campaign for better treatment.

A Century of Dishonor combines government documents, first-hand accounts, and the interpretation by the author. In her first introductory paragraph, she asks “[w]hat was the nature of the Indians’ right to the country in which they were living when the continent of North America was discovered?” The following pages are her effort to answer that question and to demonstrate the lack of faith with which the federal government had entered into treaties and agreements with Native Americans.

Library of Congress

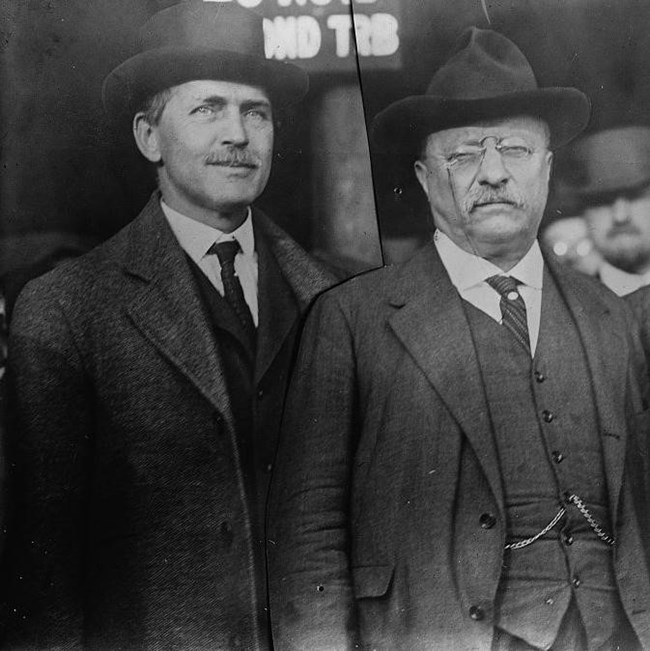

During James A. Garfield’s nine terms as an Ohio congressman, the subject of Indian Affairs came up frequently. Many of the celebrated US Army officers who had fought in the Civil War were sent to explore and settle new territories which would become states as part of the Westward Expansion. In 1868, Garfield attempted to pass a bill which would have given control over the Bureau of Indian Affairs to the War Department, taking responsibility away from the Department of the Interior, which he referred to as “so spotted with fraud, so tainted with corruption” as to be “a stench in the nostrils of all good men.” The bill ultimately failed, and the Department of the Interior remained in charge of Indian affairs in the American West. Garfield’s overall opinion of the Native American tribes whose lands were administered by the Interior, as biographer Allan Peskin mildly stated, “did not show Garfield at his best.” In later years, and closer to the publication of Helen Hunt Jackson’s book, Garfield’s dim view of Native Americans did turn around. He was even selected to meet with the Flathead Indians as a representative, and took his furthest trip into the West to do.

Library of Congress

While Helen Hunt Jackson’s book did little to dissuade American politicians from their continued push towards settlement of lands formerly promised to Native American tribes, in time the message of the book compelled many readers to petition their government for better treatment of the Indians and ultimately reform the nature of the Bureau of Indian Affairs under leadership of the Department of the Interior. The book, as it sits in the Garfield Memorial Library is one of many examples of the complex, painful, and revealing episodes in the forming of American history.

NPS

For more information on the Sand Creek Massacre, please visit our colleagues at Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site: https://www.nps.gov/sand/index.htm

Read more about the National Park Service Native American Heritage resources at: https://www.nps.gov/americanindian/?

Additional Reading & Bibliography:

Jackson, Helen Hunt. A Century of Dishonor: A Sketch of the United States Dealings With Some of the Indian Tribes. Haper & Brothers, New York, 1881.

Nunis, Doyce B. Southern California Quarterly 47, no. 3 (1965): 343. Accessed June 7, 2020. doi:10.2307/41169954.