Last updated: April 2, 2024

Article

50 Nifty Finds #45: Holding the Line

The National Park Service (NPS) was only 26 years old when the United States entered World War II. The young bureau faced very real threats to its mission, with increasing pressure to contribute its natural and cultural resources to the war effort even as its budget and staff were slashed. Under the leadership of Newton B. Drury, the NPS was able to do its part for the war while maintaining its public trust responsibilities to the American people.

The Drums of War

When Drury became NPS director on August 20, 1940, the United States was more than a year away from entering World War II. Recognizing the increasing pressure to use NPS resources for defense purposes, one of Drury’s first tasks was to develop a set of criteria against which to evaluate the requests for war uses that would inevitably come. On November 27, 1940, he issued a memorandum to guide superintendents in evaluating applications for use from national defense industries before submitting them to the Washington Office. Key issues to consider were that:

-

Park lands were necessary for the proposed use.

-

Proposed use would not cause irreparable damage to park values.

-

Evidence that alternative areas other than NPS lands had been considered and other resources exhausted.

-

If the use of park lands was deemed essential, conditions to protect park values (to include in a special use permit) would be identified.

-

Determination of whether the applicant was prepared to pay for repair of damages and restoration of grounds at the termination of the permitted use.

Convenience or expediency weren’t acceptable justifications. Drury insisted that the irreplaceable treasures entrusted to the NPS should not be sacrificed until all other sources available had been exhausted. This “last resort” approach usually resulted in the discovery of resources outside of parks that could be used instead.

Public Trustees

In 1942 the NPS decided not to request exemptions for any of its personnel from service in the armed forces or civil defense positions. Some employees expressed concern this meant that their work was no longer considered important. In October 1942 Drury responded that,

Our task is still important, and now is more exacting than ever. We are trustees for a significant part of America’s cultural heritage; and in so far as is humanly possible, with full recognition of the needs of the war, the American people expect us to strive to hold it intact.

By necessity, however, NPS war activities were limited to a strict minimum of administration, protection, and maintenance duties. All 2,539 Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) employees assigned to the NPS were discharged or transferred to other activities by the end of 1942. Staffing levels declined further throughout the war years. Before the outbreak of war, on June 30, 1941, the NPS had 5,145 permanent full-time positions. Four years later that number was 1,577. The effects of fewer employees were worsened by the 40-hour work week implemented in 1940 due to requirements of the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938.

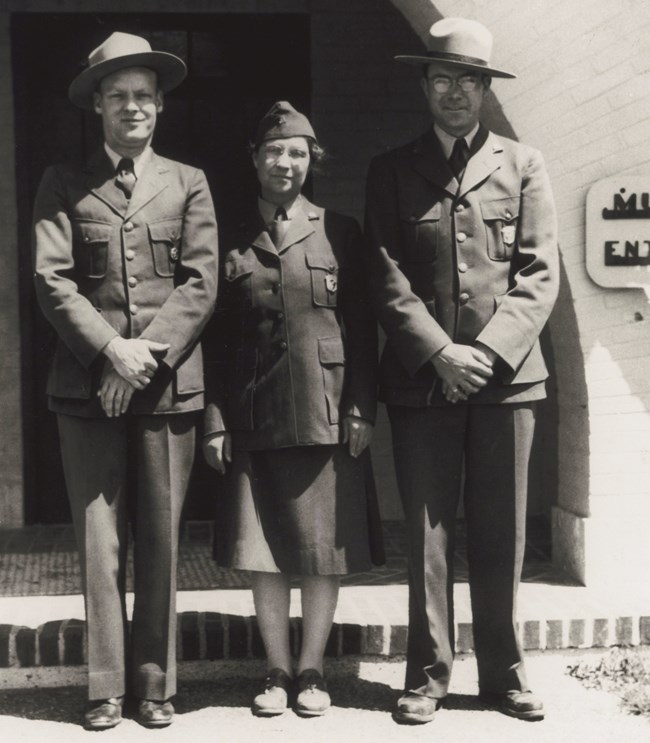

Unlike American industry, the NPS didn’t replace the large numbers of men serving in the armed forces with women. Herbert Kahler, NPS chief historian from 1954 to 1964, noted the NPS “never really gave serious thought to using women during WWII.” Although a few women managed to turn their war service appointments into NPS careers, most could be regarded as substitute rangers, as their experiences were akin to substitute teaching—they were called in as needed with few prospects for longer-term employment.

A few parks benefited from labor provided by conscientious objectors. A maximum of five Civilian Public Service (CPS) camps were approved for the NPS at any one time. They were primarily used to replace CCC labor for forest protection at Blue Ridge Parkway and Shenandoah, Great Smoky Mountains, Glacier, and Sequoia-Kings Canyon national parks. On average each camp consisted of 115 men. They were trained in firefighting, fire-hazard reduction, blister-rust control (a fungal disease that affects pine trees), and maintenance of roads, trails, bridges, and telephone lines.

The NPS budget decreased from $9.3 million in 1941 to about $4.5 million in 1944.

An Office with A View

Even the NPS location in Washington, DC, was affected by the war. To make space available to other federal agencies necessary to the war effort, the NPS, US Fish and Wildlife Service, Office of Indian Affairs, and other bureaus were to be relocated to Chicago, Illinois. In May 1942 the Advisory Board on National Parks, Historic Sites, Buildings, and Monuments objected to no avail, noting that it was “against the interest of the Service and is detrimental to the general interest of the national defense and war effort.” The move began on August 28 and was completed in October, at a cost of $63,480. Many employees chose not to go and left the NPS instead. A total of 146 employees relocated, and 26 more were hired in Chicago. A small “liaison group” headed by Associate Director Arthur E. Demaray remained in Washington.

In 1944 the Interim Committee of the Advisory Board reaffirmed the board’s earlier position noting,

Removal of the headquarters from the seat of Government has seriously hindered the work of the Service, has made its administration more difficult, and has made impossible the close and immediate liaison with other branches of the Government, with the Army and Navy, and with the Congress that has become more than ever imperative because of the great demands that are being made upon the facilities of the Service in connection with the needs of the war effort of the Nation.

The committee determined that the space benefit of moving the NPS from the Department of the Interior building was “almost negligible” and made “entirely unnecessary” by the government’s decision to build new permanent and temporary buildings “on a gigantic scale.” Yet the financial cost was significant. It estimated that if the NPS remained in Chicago through 1945 the total cost of the relocation would be $390,813. In renewing its protest, the committee described it as “an ill-conceived, unrealistic measure, extravagantly uneconomical, unjustified by any needs of other branches of the Government, harmful to the Service, and detrimental to the war effort and the public interest.” NPS headquarters didn’t move back to Washington until 1947 and, if the committee’s figures were correct, the final cost would have been closer to $600,000.

Taking Stock

In his 1942 annual report to the secretary of the Interior, Drury wrote that,

The stress of war has compelled the Service to take stock of its primary functions and responsibilities. As trustee for many of the great things of America—areas of outstanding natural beauty, scientific interest, and historical significance—the National Park Service has realized its obligation to harmonize its activities with those relating to the war, aiding wherever possible, and striving to hold intact those things entrusted to it—the properties themselves, the basic organization trained to perform its tasks, and, most important of all, the uniquely American concept under which the national parks are preserved inviolate for the present and future benefit of all of our people.

At the outbreak of war, the NPS administered about 21.5 million acres of land “possessed of varied scenic, scientific, historical, archeological, and recreational resources.” Many of these resources could have been manufactured into materials for war. Drury resisted wholesale calls to cut hardwood forests, slaughter wildlife for food, submit historic ordnance and statues in historical parks for scrap metal drives, and mine for minerals under national parks, sticking steadfastly to his “last resort” approach.

Even as Drury fought to protect park resources, however, he was careful to ensure that the NPS wasn’t seen as unpatriotic or sabotaging the war effort. This required creative solutions or judicious compromise to keep NPS resources unimpaired. For example, for several years he fought attempts to log hardwood trees in Olympic National Park for airplane timber. Yet in 1943 the NPS sold fallen or badly leaning Douglas fir trees after a blow-down event. It was a win-win situation. The fallen timber was a fire hazard for the park; its sale to a timber company resulted in two million board feet for the war effort and less fuel loading for the park. Dead chestnut trees in Shenandoah and Great Smoky Mountains national parks and Blue Ridge Parkway were sold to tannin extractors for leather tanning while also reducing fire risks.

World War II revived and intensified the issue of grazing in national parks. Lessons learned from World War I, when cattle were allowed in several western national parks, showed that the benefit to the nation’s food supply was negligible while damage to parks was significant. Impacts included contamination of water sources, trampling and destruction of plant cover, and erosion. Moreover, it took a decade to eliminate grazing in those parks after the war ended.

Drury wasn’t anxious to repeat this approach. A study was made of all areas throughout the National Park System and increases in grazing allotments in certain areas was authorized as an emergency contribution to the food-production program. However, Drury developed criteria for where grazing could or would not be permitted. While that formula allowed for a 28-percent increase in cattle grazing, requests for increases in both cattle and sheep grazing in available areas only amounted to 20.9 percent. Even as some temporary increases in grazing permits were authorized, the secretary of the Interior reaffirmed the long-established policy of eliminating grazing from national parks. Independent review of applications to allow increased used of park lands for grazing during the 1944 drought found that there was sufficient rangeland elsewhere, and the requests were denied.

Although Drury wouldn’t allow hunting in national parks, normal reductions of surplus animals did contribute to the national food supply. Elk reductions in Yellowstone National Park during the winter of 1942–43 resulted in 172,750 pounds of meat, and 160,000 of bison meat were supplied the next year. Reduction in deer herds provided 20,209 pounds of venison (300 animals) from Zion and 9,500 pounds (112 animals) from Rocky Mountain National Park. Rocky Mountain also culled about 296 elk (74,000 pounds of meat).

In fall 1942 the NPS was pressured to sacrifice its historic ordnance and statuary to the scrap-metal drive. A bill was even introduced into the House of Representatives that would have required the NPS to do so. On November 17, 1942, Drury wrote to the War Production Board that,

While a considerable quantity of non-ferrous scrap can be, and is being, salvaged in historical areas of the NPS, we have not unnaturally taken the view that rare and irreplaceable historic cannons as well as memorials of historic character and artistic excellence ought not to be scrapped until the national stockpile of useless and non-historic and non-artistic metal objects has been utterly exhausted. For instance, the brass and bronze trimmings of a government building can be replaced at virtually the original cost after the war; but a bonze cannon captured at Yorktown or Saratoga and the original of a statue of artistic or inspirational excellence can never be duplicated at any price. In many cases statues and memorials symbolize and express far better than printed words or patriotic speeches the very ideals for which we are fighting. It is for this reason that patriotic posters and patriotic literature bear representations of the Statue of Liberty, while war savings stamps and war bond advertisements carry pictures of French’s Statue of the Minute Man, symbol of American alertness and victory. As for the trophy ordnance, a Nation without such reminders of its past victories and heroism would have little enduring pride.

As pressure continued, Drury wrote to the board on February 10, 1943, “Each war memorial in the parks represents the last possible debt-payment of the Nation to some soldier or group of soldiers in our national past. It would be of little comfort to the soldiers of the present day if such evidence of the Nation’s gratitude should come to be lightly regarded.”

The War Production Board conducted a survey of NPS cannon, statues, and other objects to better understand the nation’s war resources. It determined that these cultural resources represented 984.8 tons of non-ferrous metal. Eventually the Salvage Bureau of the War Production Board and the Office of the Chief or Ordnance came to agree with Drury’s position that all other sources should be exhausted first. It was agreed that cannon predating 1865 and other historical and artistic objects wouldn’t be scrapped at that time. Indeed, the Office of the Chief of Ordnance saved other historic cannon that came into their possession; the NPS acquired additional cannon for Saratoga and Castillo de San Marcos National Monument as a result.The NPS contributed over 8.5 million pounds of metal to the scrap drive, without sacrificing its cultural resources. As Drury predicted, the need for metal never became so acute as to require sacrificing the irreplaceable.

Historic sites contributed to the war effort in other ways. Cabrillo and Fort Pulaski national monuments were devoted exclusively to war use. Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Site, near President Roosevelt’s home, housed up to 35 members of the president’s Secret Service detail from 1941 to 1943. After they left, the US Military Police used the entire third floor of the mansion for the duration of the war. Beginning in late 1943 Superintendent Gertrude Cooper established a canteen where soldiers could have coffee and “dance or chat or play games” with local women. The NPS issued a series of permits to the War Department at Bandelier National Monument for quartering personnel and their families engaged in the Los Alamos phase of the atomic bomb project. Fort Jefferson National Monument (now Dry Tortugas National Park) was closed to the public for use as a US Navy radar station. Declassified documents show that the Chemical Warfare Service also conducted testing on the unoccupied keys within the park.

In 1943 Drury issued two memos that permitted agricultural uses of lands in historical areas where agriculture was part of the site during its period of significance. Leases were let at Gettysburg and Saratoga national military parks, Colonial National Historical Park, and other sites. Once again Drury found a compromise that supported war work but served NPS purposes. Restoring cornfields, peach orchards, and pastures contributed to the food supply while restoring cultural landscapes and reducing NPS maintenance costs.

Throughout the war the NPS issued 2,396 permits for use of its areas, facilities, and resources directly connected to the war effort. More than half were for minor short-term uses such as field exercises, maneuvers, overnight bivouacking, and using park roads to transport materials connected with the war program. The remaining authorizations were for occupancy and use of NPS facilities, using natural resources such as minerals, timber, forage, gravel, water; exclusive use of concessioner facilities; exclusive rights-of-way; and the loan or transfer of equipment. In addition, 9,580 acres were permanent transferred to the US Army or US Navy for their use.

Patriotic Messaging

The National Parks Advisory Board noted in October 1940 that the NPS’s interpretation program “is one of the most valuable contributions by any Federal agency in promoting patriotism, in sustaining morale, and understanding the fundamental principals of Americna democracy, and in inspiring love for our country.” To aid these causes during the war, the NPS endeavored to keep parks open to everyone who could get to them. It also gave free entry to all members of the armed forces in uniform.

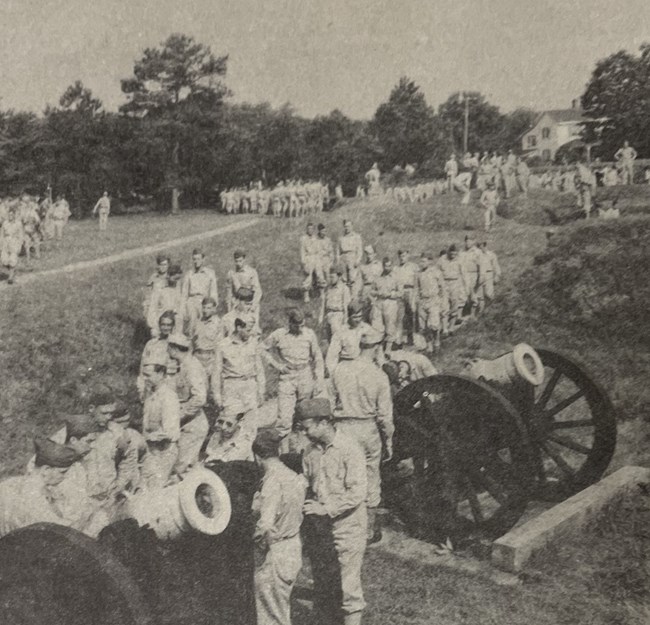

Visits to NPS historical parks increased as people sought to “reconsecrate themselves to the ideals for which this country stands by direct emotional experience on soil made sacred by the heroism and unselfish patriotism of our forefathers.” In response, the NPS interpretation program emphasized historical stories that addressed liberty, democracy, love of country, and offering greater service. New exhibits, lectures, and self-guided tours were created in some areas. Battlefield parks in particular created new ways to explain military objectives. Special exercises and celebrations supported by patriotic societies and groups were held throughout the war.

The NPS also provided more than 150,000 free copies of park information circulars to Army Service Center libraries; United Service Organizations (USO) lounges; Office of War Information (OWI) for its libraries in Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and India; and prisoner of war camps.

Although it did the best it could to meet demand, the NPS noted in 1944 that the OWI’s paper-saving policy necessary for the prosecution of the war had set the NPS program of providing popular interpretive publications back 20 years. This wasn’t an exaggeration. The NPS’s 1945 printing budget was $25,000—the same as it had been in 1924.

Nature’s Medicine

From 1934 to about 1940 the NPS built 46 Recreation Demonstration Area (RDA) projects, consisting of vacation and wayside areas located near urban areas. Some of these sites allowed the NPS to provide camping facilities for British and French sailors working in American shipyards. Coordinating through the US Navy, the NPS accommodated 22,353 foreign sailors at Hopewell Village National Historic Site (formerly known as the French Creek Recreation Demonstration Area), five vacant CCC camps, and RDAs in New Hampshire, Maryland, South Carolina, Virginia, and California. Most of the RDAs eventually became state parks.

In spring 1941 the US Army recognized its need to provide inexpensive facilities for soldiers on leave or places that could provide rest and relief for a week or two during the grind of ongoing training. The NPS was called upon to help with planning, and CCC workers were used to construct army rest camps. By June 30, 1942, 33 camps capable of accomodating 20,000 people were constructed in 23 states and the District of Columbia. Most were near cities or larger populated areas.

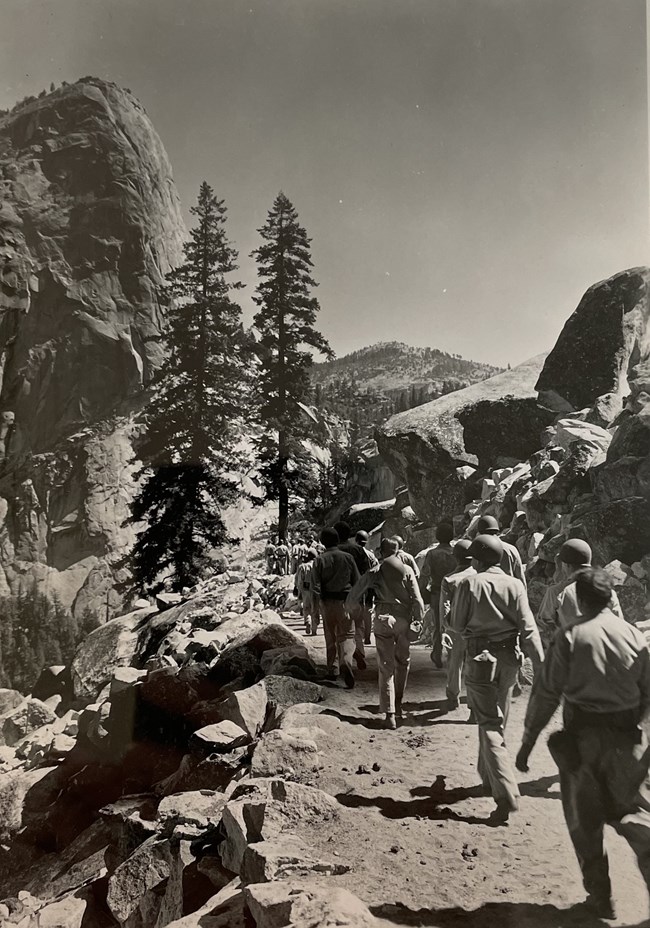

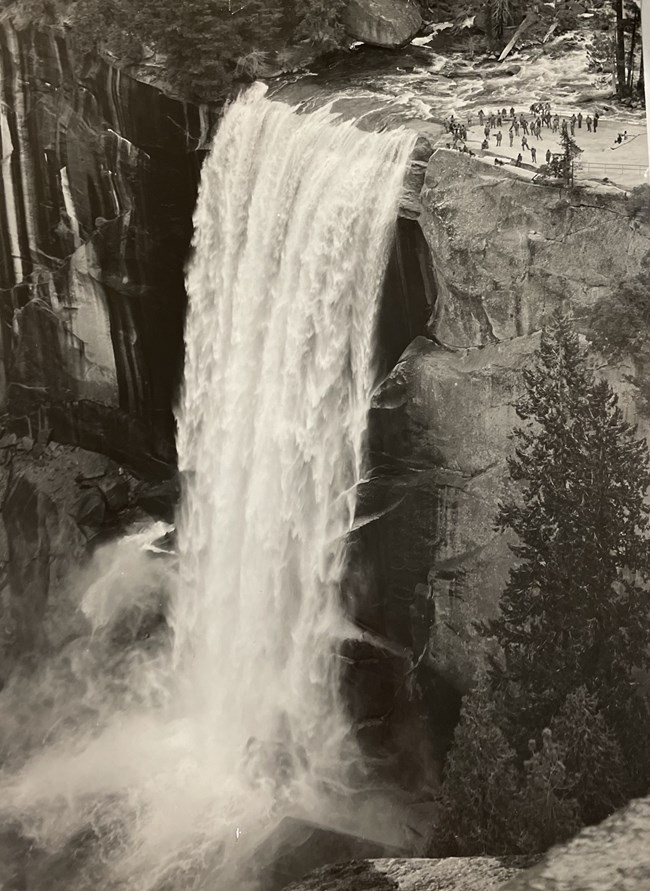

Although the NPS contributed to the war effort in many ways, it determined that in wartime the best function of the National Park System was to provide a place where members of the armed forces and civilians could “retire to restore shattered nerves and to recuperate physically and mentally for war tasks still ahead of them.” Military personnel quickly became a common sight in national parks. By fiscal year 1943, the number had soared to 1.65 million miltary visitors, more than three times those who visited in fiscal year 1942.

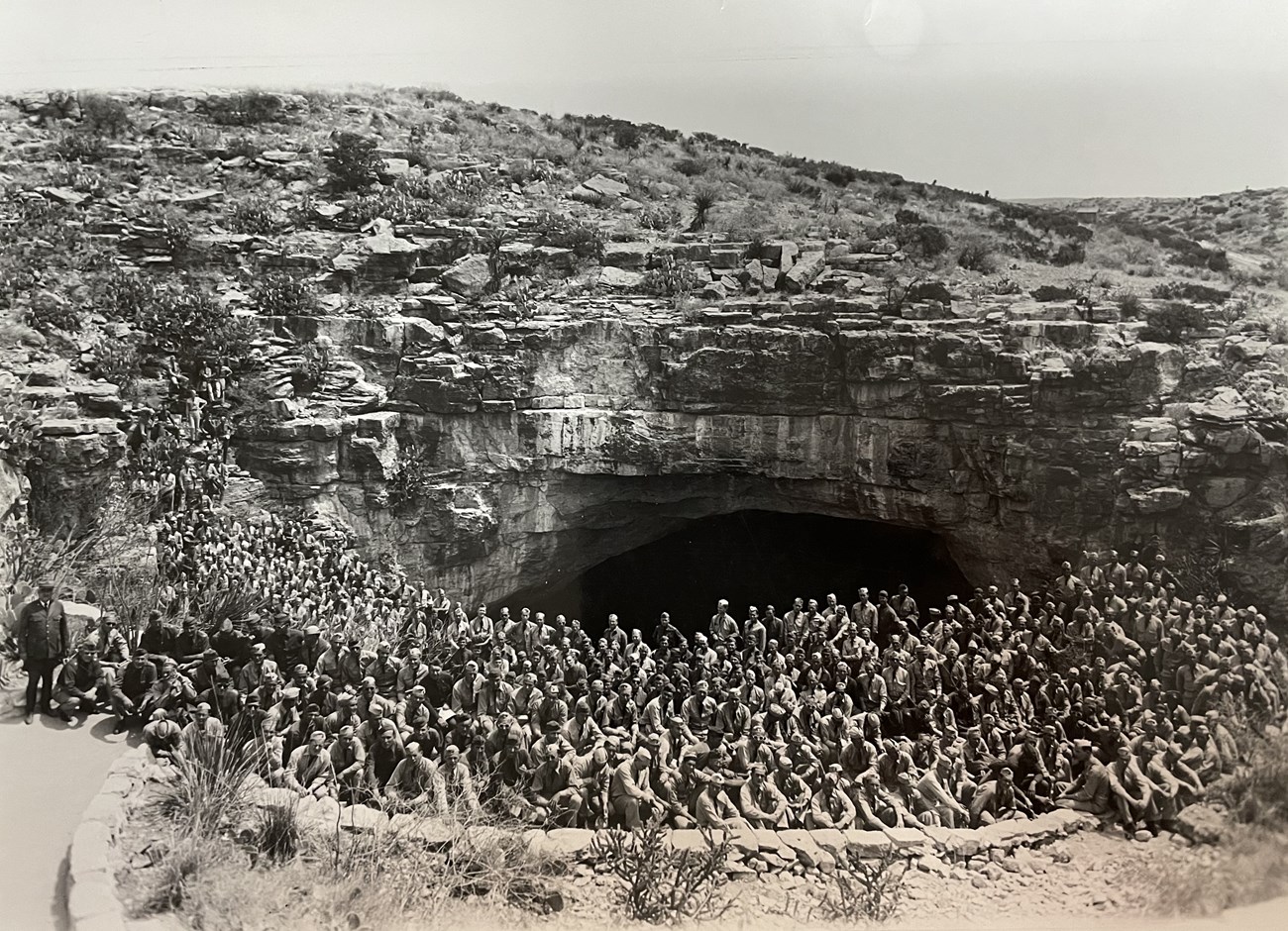

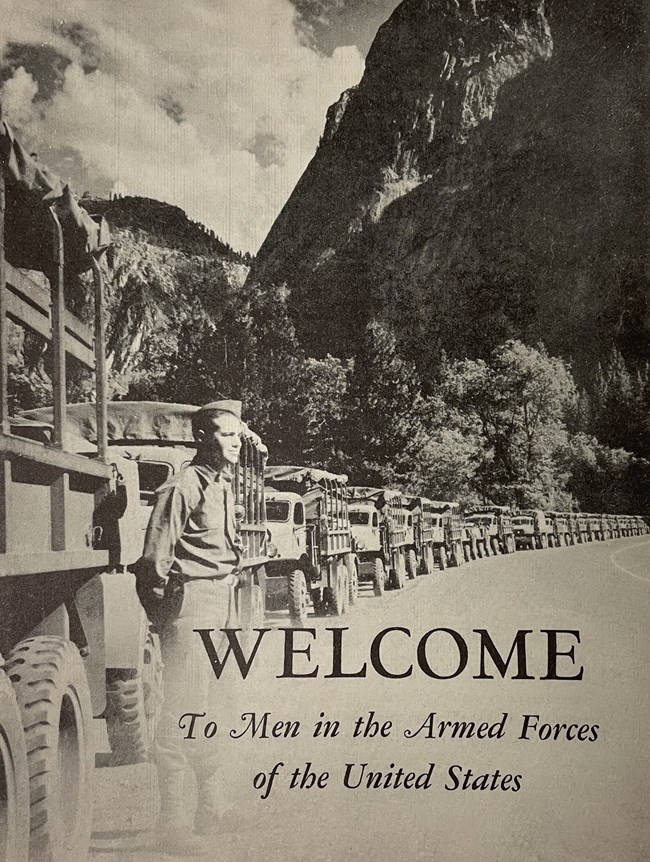

Hundreds of thousands of soldiers and sailors found “recreation and patriotic stimulation” in national parks and monuments. The NPS distributed over 200,000 “Welcome to the Members of the Armed Forces of the United States” pamphlets in five editions printed between 1942 and 1945. It shared the mission and organizational structure of the NPS, drew connections to former military protection of some national parks, highlighted the patriotism of national parks, and provided a list of rules for service members to follow when visiting parks.

The US Army developed a recreational center at McKinley Hotel, formerly operated by the Alaska Railroad, at Mount McKinley (now Denali) National Park.

The brochure created for it declared that the camp offered “a million-dollar mansion” in the form of the park hotel where they could find “undisturbed peace—probably for the first time since you joined the army. There are no first sergeants around to roll you out of bed in the morning.” The dining room offered “the best food served north of Seattle” and promised “eggs cooked within 30 seconds of the desired time on electrically-timed boilers.” In addition to traditional national park outdoor pursuits of hiking, horseback riding, and sightseeing, servicemen could engage in pee-wee golf, archery, tennis, baseball, boxing, football, soccer, horseshoes, volleyball, and badminton. From October to April, skiing, tobogganing, and ice skating were available. Sports equipment, art supplies, leatherworking materials and tools, cards, and boardgames were provided. There was even a dark room where, for a small fee, they could print their own photographs. Rooms cost $1.05 per day for officers and $0.55 for enlisted personnel. Meals were $0.40 each. The popularity of the facilities led the army in 1943 to assist the park with desperately needed construction, utility, and maintenance projects. As troop levels in Alaska drew down, the army closed the recreation camp on March 1, 1945.

Worth Fighting For

American advertising campaigns during World War II encouraged people to express their patriotism by supporting the war effort through cooperation and personal sacrifice. Motivational advertisements sought to make emotional connections with the home front to remind Americans why the United States was at war, what could be lost, and why losing the war wasn’t an option.

In summer 1942 a song titled “This Is Worth Fighting For” became popular. The song, like the advertising campaigns, encouraged the home front to think about protecting American values and their ways of life. For the NPS, “Worth Fighting For” became the title of a fire prevention poster created by OWI.

The poster features a square-jawed, muscled park ranger standing in the middle of an image split by a large V (suggesting the “V for Victory” campaign). The background features an idyllic forest scene with mountains and lakes. In the foreground the ranger stands in a burnt-out landscape with red skies and charred trees. Beneath him is the tag line “Help Your Park Ranger Prevent Fires.” Although it was printed by the Government Printing Office (GPO), the exact date of publication, artist, and print run are unknown.

Interestingly, two of the three examples of this poster in the NPS History Collection are printed on unstretched canvas rather than paper. One of the canvas examples was received from Great Smoky Mountains National Park along with other WWII-related materials in 1975. Both appear to predate modern Giclée inkjet printing methods. All three posters have same GPO number. Although the canvas posters would have been more durable than paper posters in many park settings, no information about them has been found.

Another WWII propaganda poster in the NPS History Collection is “Don’t Let Him Come Home to This.” It features a soldier standing in a burnt-out landscape, one foot resting on a charred tree trunk. Charred trees behind him punctuate the orange sky. Beneath the scene is “Prevent Forest Fires!” Although the artist is unknown, it was printed by the GPO in 1944 in cooperation with the OWI.

The effectiveness of the posters for preventing forest fires is unclear, partly because no information has been found about how many posters were printed, where they were displayed, or for how long. The fact that there were fewer people (visitors and employees) in parks during the war would have reduced fire risks significantly on its own. In the summary report of its activities during wartime, the NPS reported that “park forests neither gained nor lost ground because of the war. Losses by fire, insects, and disease have been normal or less than normal.”

The Lure of the Parks

In early December 1942 a conference was held among representatives of the NPS, national park concessioners, the US Navy, and the US Army to discuss use of park concession facilities for war purposes. Although the Department of Defense’s war powers meant that it could seize facilities, it followed a policy to take only those properties where mutual agreement was reached. Hotels and other building in parks like Acadia, Bandelier, Mammoth Cave, Mount Rainier, and Olympic; Boulder Dam National Recreational Area (now Lake Mead National Recreation Area); and the National Capital Parks were turned over to the miltary for defense, training, or housing purposes. In June 1943 the Ahwahnee Hotel at Yosemite National Park became a convalescent hospital for the navy.

Beyond the exclusive military use of some concessioner facilities, the war’s travel restrictions also led many concessioners to voluntary close facilities. Transportation companies that brought visitors to parks saw their ridership change in support of the war effort. Even as some railways, bus lines, and other transportation companies created advertisements that discouraged unnecessary travel, a few used the lure of the parks to evoke an idyllic postwar future.

In 1942 Greyhound Bus Lines changed its slogan from “See America Now!” to “SERVE American Now!—So You Can SEE America Later.” Noting that “the war effort came first” with the company, its advertisements positioned the company as a transportation resource for service men and women, war workers, farm help, and others supporting the war effort.

Suggesting a future return to normalcy, one of its 1944 magazine advertisements features a woman and soldier holding hands in front of a lake and mountain splendor, with a Greyhound bus driving along the road at the edge of the lake. The text accompanying the image reads:

This Will Never Change! But when he comes back there’ll be newer, finer ways to enjoy the land he fought for. Maybe we will take our post-war meals in pink, green, and purple pills…maybe we’ll swoosh to work in rocket cars…maybe so!

But there are a few things that eleven million G.I. Joes want to see just as they left them—just as they’ve dreamed about them through all these long months. Such as the unchanging love of a girl who waited—such as the magnificent National Parks and playgrounds that are the heritage of every American—all the exciting and wonderful things there are to see and do along seventy thousand miles of American highways!

These are not going to change—but it’s going to be a lot easier to visit and enjoy these and all natural wonders of This Amazing America than it has ever been before—Greyhound promises you that.

In the days after Victory look for finer, roomier motor coaches—for more spacious, better equipped terminals (perhaps with helicopter landing decks!). Expect great things of Greyhound in the good days to come. [Emphasis in the original]

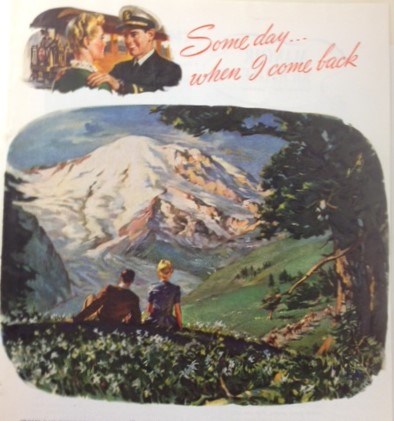

Railway companies also used the patriotic theme while tugging at personal heartstrings. The Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul, and Pacific Railroad (CMStP&P, better known as the Milwaukee Road) published “Some Day When I Come Back”, a magazine advertisement featuring a small image of a sailor saying goodbye to a woman while the main image has them sitting in a flower meadow looking toward a glacier-covered mountain. It reads in part,

Some day when I come back, we’ll travel together on this Olympian—we’ll take it on the honeymoon that war does not give us time for now.

Hand in hand—just you and I—we’ll wander through the mystic wonderland that’s Yellowstone Park and see the spouting geysers, its bubbling paint pots, its multi-colored terraces, its breathtaking canyon…

We’ll stay in a chalet in Paradise Vally at towering Mount Rainier—stroll through flower-decked Alpine meadows to glaciers and ice caves and snow fields. It won’t be too long till we realize this dream, I hope. It’s one reward victory will bring—to us.

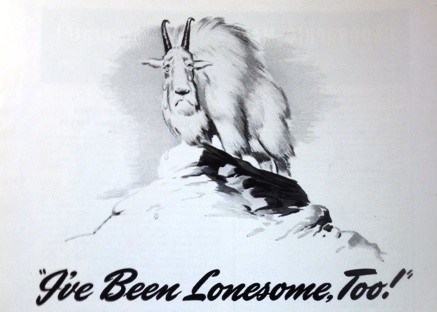

The Great Northern Railway took a different approach with its 1945 “I’ve Been Lonesome Too” advertisement, which features a sad mountain goat. The goat laments the lack of visitors, saying in part,

Summertime here in Glacier National Park used to be fun for me…But this year—like in 1943 and 1944—folks are coming to Glacier Park because the hotels and chalets are closed. Maybe you’ve been lonesome for the lakes and mountains and good times in Glacier Park. Well, I’ve been lonesome for you, too!

What a great day it will be when you can all come back here again after the war! The Park will be more beautiful, more inviting than ever. And Great Northern Railway will have even finer, faster trains to bring you here. Yes, some summer soon we’ll have more fun together in Glacier National Park in Montana!

The Rush of Peace

Although the war wasn’t over, and rationing was still in place, travel to national parks began to increase again after Victory in Europe (V-E) Day on May 8, 1945. When travel restrictions were lifted after Victory Over Japan (V-J) Day on August 15, 1945, Drury wrote,

The floodgates of travel opened immediately after VJ Day. For months thereafter all previous monthly records for number of visitors were broken; parks whose remoteness has rendered them inaccessible to all but a handful of visitors during the war were suddenly hosts to great crowds for which neither the park staffs nor the concessioners were prepared.

More than 21.6 million people visited national parks and monuments in 1946—a new record—yet staffing levels remained low for both the NPS and concession operators. Personnel ceilings and lack of funds prevented the NPS from making large increases in staffing levels. By June 30, 1946, there were 1,795 permanent employees (208 more than in 1945); an additional 1,524 temporary rangers had been hired for the summer season. However, the loss of pre-war CCC workers and the 40-hour work week (which had been 48 hours in 1938) resulted in a significant net loss of employees for the NPS, even as visitation soared.

In addition, NPS and concession facilities needed maintenance and improvements. Materials, supplies, experienced workers, food, housing, busses, and other equipment were still scarce. Drury noted that “most [visitors] accepted cheerfully the inconveniences of a period of reconversion [to peacetime]. There were complaints, of course, but the number was infinitesimal in comparison to the millions who were happy to have an opportunity once again to visit the national parks.”

As the NPS celebrated its 30th anniversary on August 25, 1946, it was in dire need of money, staff, and studies and plans for existing and new units added to the National Park System, as well as a comprehensive program to rehabilitate its roads, buildings, exhibits, and other infrastructure. It would largely have to wait another decade before 1955’s Mission 66 program provided the funding to make any serious progress in these areas.

Sources

Jones, John Bush. (2009). All-out For Victory! Magazine Advertising and the World War II Homefront. University Press of New England: Hanover and London.

National Park Service. (1942, January-February). Park Service Bulletin, Vol. XII, No. 1. NPS History Collection (HFCA 1645), Harpers Ferry, WV. Available online at http://npshistory.com/newsletters/courier/bulletin/v12n1.pdf

National Park Service. (1942, June). Memorandum Regarding Personnel and Policy Changes, Vol. XII, No. 2. NPS History Collection (HFCA 1645), Harpers Ferry, WV. Available online at http://npshistory.com/newsletters/courier/bulletin/v12n2.pdf

National Park Service. (1942). Annual Report of the Director of the National Park Service to the Secretary of the Interior, Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1942. NPS History Collection (HFCA 1645), Harpers Ferry Center, WV.

National Park Service. (1942, October). Memorandum Regarding Personnel and Policy Changes, Vol. XII, No. 3. NPS History Collection (HFCA 1645), Harpers Ferry, WV. Available online at http://npshistory.com/newsletters/courier/bulletin/v12n3.pdf

National Park Service. (1943). Annual Report of the Director of the National Park Service to the Secretary of the Interior, Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1943. NPS History Collection (HFCA 1645), Harpers Ferry Center, WV.

National Park Service. (1944). Annual Report of the Director of the National Park Service to the Secretary of the Interior, Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1944. NPS History Collection (HFCA 1645), Harpers Ferry Center, WV.

National Park Service. (1945). Annual Report of the Director of the National Park Service to the Secretary of the Interior, Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1945. NPS History Collection (HFCA 1645), Harpers Ferry Center, WV.

National Park Service. (1945). National Park Service War Work December 7, 1941, to June 30, 1944, With Supplement to October 1945. NPS History Collection (HFCA 1645), Harpers Ferry, WV.

National Park Service. (1946). Annual Report of the Director of the National Park Service to the Secretary of the Interior, Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1946. NPS History Collection (HFCA 1645), Harpers Ferry Center, WV.

National Park Service. (1947). Annual Report of the Director of the National Park Service to the Secretary of the Interior, Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1946. NPS History Collection (HFCA 1645), Harpers Ferry Center, WV.

NPS History Collection. (2022, August 11). “Substitute Rangers.” Accessed March 31, 2024, at https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/substitute-rangers.htm

Norris, Frank. (2021, October 12). “World War II Recreation Camps at Denali.” Accessed March 30, 2024, at https://www.nps.gov/articles/dena-wwii-recreation.htm

Unrau, Harlan D. and Williss, G. Frank. (1983, September). Administrative History: Expansion of the National Park Service in the 1930s. Available online at https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/unrau-williss/adhi4i.htm

Tags

- bandelier national monument

- blue ridge parkway

- cabrillo national monument

- carlsbad caverns national park

- castillo de san marcos national monument

- colonial national historical park

- denali national park & preserve

- dry tortugas national park

- fort pulaski national monument

- gettysburg national military park

- glacier national park

- great smoky mountains national park

- olympic national park

- rocky mountain national park

- saratoga national historical park

- scotts bluff national monument

- sequoia & kings canyon national parks

- shenandoah national park

- vanderbilt mansion national historic site

- yellowstone national park

- yosemite national park

- zion national park

- nps history

- nps history collection

- hfc

- parks wwii

- second world war

- us army

- us navy

- recreational demonstration area

- recreational demonstration areas

- recreation camp

- fire

- fire prevention

- propaganda

- advertisements

- transportation

- railroad

- wwii history

- wwii home front

- wwii homefront

- armed forces

- american military

- nps director

- nps directors

- grazing

- forests

- poster

- posters

- ccc

- civilian conservation corps

- 50 nifty finds