Last updated: February 8, 2024

Article

50 Nifty Finds #43: Environman

It’s a bird! It’s a plane! It’s … Environman? While it may sound like a Saturday morning superhero, Environman was a National Park Service (NPS) symbol for its environmental education activities in the 1970s. Beginning in 1967 the NPS became a leader in environmental conservation education, which then-Director George B. Hartzog, Jr saw as crucial to the survival of the parks and the planet. Many of the key ideas from the 1970s programs echo in today’s NPS climate change interpretation and education.

Looking Outward

Education has been a central part of its mission since the NPS was created on August 25, 1916. In 1917 Robert Sterling Yard became the first chief of the Education Division. As a testament to how important NPS Director Stephen T. Mather thought the position was, when the 1917 NPS budget didn’t include enough money to pay Yard’s salary, Mather paid him from his own pocket. In 1918 Secretary of the Interior Franklin K. Lane directed Mather, "The educational, as well as the recreational, use of the national parks should be encouraged in every practicable way.”

Education, then, is nothing new to the NPS. From the early 1920s through the mid-1960s, however, interpretation concentrated on introducing visitors to specific features of a site rather than relating the significance of the site to the visitor and society as a whole. This issue was on the mind of Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall in spring 1967 when he discussed “the application of modern communication methods to interpretation of the new conservation” with NPS Director George B. Hartzog Jr. In their conversation Udall quoted Ansel Adams,

It is my conviction that the interpretive work of the National Park Service, excellent as it is within the parks and monuments, should be expanded to provide a stimulating and informative interpretation of the national park idea to the people at large throughout the land.

Hartzog believed in the urgency of understanding and changing our relationship with the planet and its resources. As director of the NPS, he also had a very practical interest in spreading broader conservation messages. Throughout the 1960s parks experienced increasing visitation, recurring traffic jams, overflowing campgrounds, and rising crime rates. Human impacts on native vegetation and other natural resources became increasingly common. Of course, people weren’t coming to parks to destroy them; they came to use and enjoy them. Likely for the first time, the NPS recognized that people actually could love their parks to death. Hartzog reasoned that the NPS needed to get to the public and raise their environmental consciousness before they arrived at a park. As a result, under Hartzog’s direction, the NPS became a leader in the emerging environmental education movement in the late 1960s.

Environmental Conservation

In July 1967 an NPS task force released a report called A Plan of Cooperation for Environmental Conservation. It recommended working with schools, youth groups, public service groups, and conservation organizations throughout the country to teach children “an appreciative and critical awareness of their environment, particularly that awareness which recognizes the interactions of natural and human processes.”

In December that year Bill Everhart noted that interpreting park resources to park visitors wasn’t enough.

First, our interpretive programs have traditionally been limited to the parks themselves. We have concentrated mostly on telling the park story to visitors. Secondly, we have had a tendency to interpret a park in terms of its resources. We have not effectively carried out an educational campaign to further the general cause of conservation. Only through an environmental approach to interpretation can an organization like ours, which has both Yosemite and the Statue of Liberty, achieve its purpose of making the park visitor’s experience fully significant. A third objective is the quality of the things we do.

Building from the task force’s report, Hartzog announced a series of new programs in a speech at Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial on February 11, 1968. He described two programs in environmental education in what he initially called “A Cooperative Program for Environmental Conservation”: the development of curricula-integrating materials for schools and the establishment of environmental study areas within parks. These programs would be developed and carried out in cooperation with local school systems. A new Office of Environmental Education was created in the NPS Washington Office to support the environmental education initiatives.

The significance Hartzog gave these programs is perhaps best summed up in a 1969 letter to the editor of The New York Times where he wrote,

We are glad we don’t have the whole burden of carrying out this life-or-death mission for humanity. But we cannot avoid doing what we are best fitted to do—both in the National Park System, and out from it. We feel that conservation in the highest sense of man-centered environmental awareness is an idea whose time has come. … I have a very real conviction that we are running out of time at the precise moment when environmental awareness is becoming a saving factor of effective proportions. We in the National Park Service are undertaking our effort not with the long faces of doom, but as open-eyed human beings for whom hopeful planetary prerogatives remain.

National Environmental Education Development (NEED)

The NEED program was created to “help the individual child come to grips with his own world by arriving at his own personal environmental ethic.” It was a process for developing environmental awareness, understanding, and values in K–12 students. It featured five “environmental strands” to be used throughout existing course studies at participating schools:

-

Variety and similarity—the inventory stage of learning; cataloging the observable components

-

Patterns—organizing the inventory into sets of thigs we can handle, either actually or intellectually

-

Interrelation and interdependence—the action stage of learning where the environmental components are studied in motion

- Continuity and change—the extension in time of continuing processes and changing action

- Adaptation and evolution—the stage involving continuous modification that may result in adjustment to prevailing conditions

These strands were “constants” running through the total environment—natural and cultural. They could be used individually with a particular subject or environmental setting, but taken in order, they represented a logical sequence of learning. The strands were used as a framework “to help a child to see, to feel, to know, and eventually to make decisions about the world.”

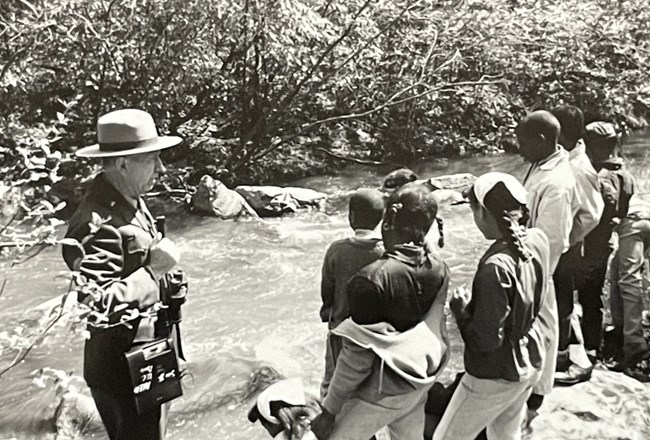

Outdoor experience was a critical part of the NEED program. The program aimed to give children this experience for at least a week at three academic grade levels. Fifth graders would learn appreciation of the environment. Seventh graders would study “man’s use—or abuse of land, air, and water.” At the high school level, environmental conservation methods would be stressed.

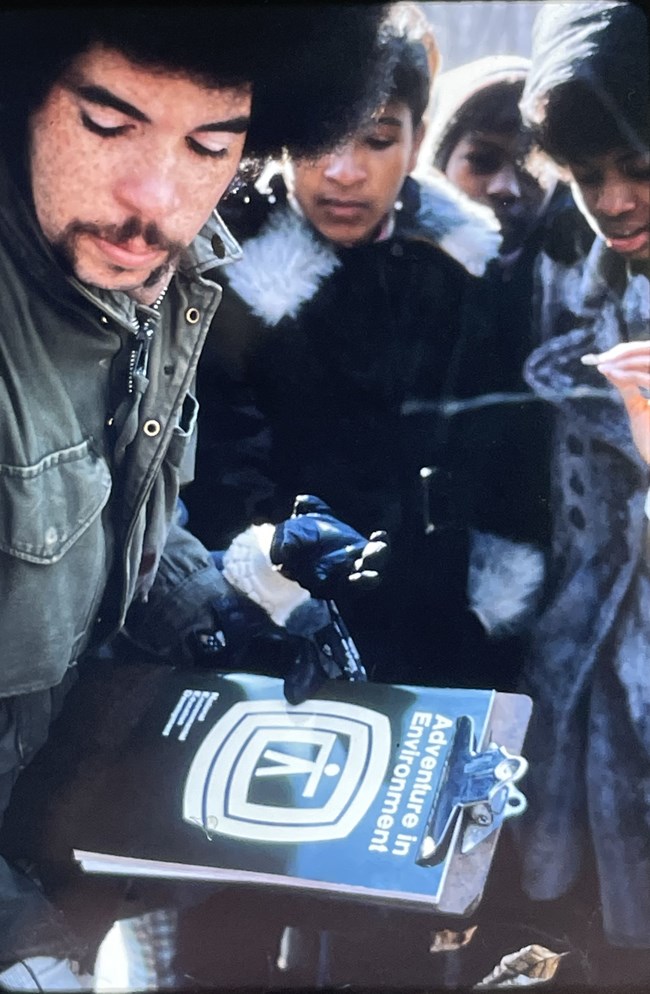

The National Park Foundation provided funding to develop, evaluate, and refine the NEED environmental education materials. It also sponsored publication of the “Adventure in Environment” program materials for K-8 grade students.

The National Park Foundation provided funding to develop, evaluate, and refine the NEED environmental education materials. It also sponsored publication of the “Adventure in Environment” program materials for K-8 grade students.

A Growing Urgency

The NPS environmental education program grew in concert with rising national concerns about environmental quality. The 1970s began with a sharp focus on the environment. President Richard M. Nixon signing the National Environmental Policy Act on January 1, 1970. The first Earth Day was marked in April that year. Even an Environmental Education Act (Public Law 91-516) passed on October 7, 1970. It authorized the United States Commissioner of Education to establish programs to “encourage understanding of policies, and support of activities, designed to enhance environmental quality and maintain ecological balance.” The law recognized the risks associated with deterioration of our environment and its ecological balance to the “strength and vitality of the people of the Nation” and made resource available to educate and inform citizens about environmental quality and ecological balance.” The law defines “environmental education” as

The educational process dealing with man’s relationship this natural and manmade surroundings, and includes the relation of population, pollution, resource allocation and depletion, conservation, transportation, technology, and urban and rural planning to the human environment.

Environman

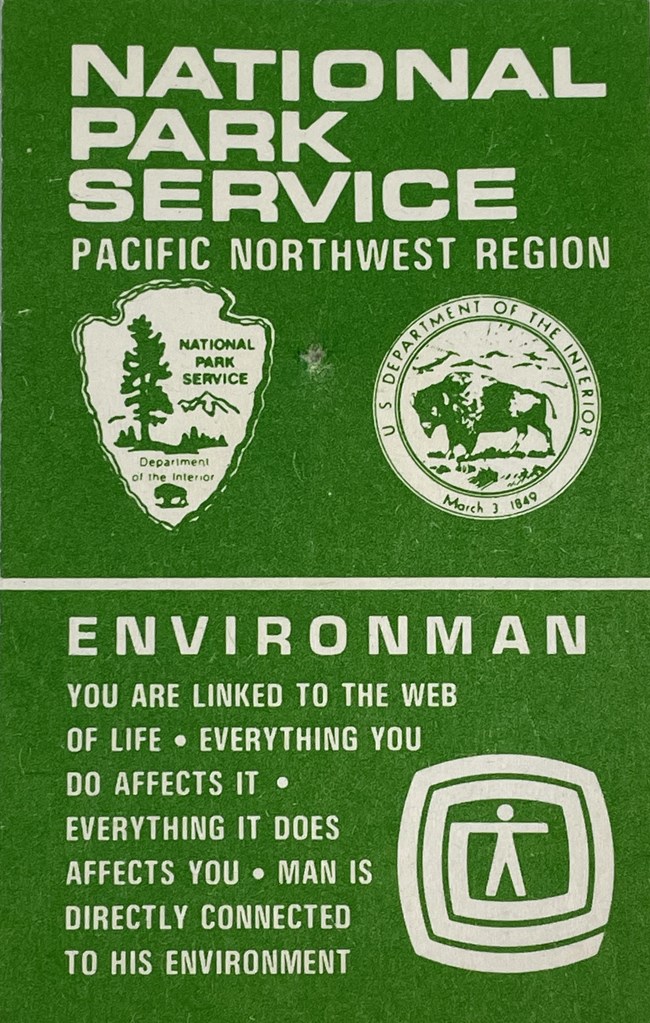

Although the history of its development is still unknown, by May 1970 the NPS Environman symbol was being used with the NPS arrowhead symbol on internal interpretive newsletters.

On December 31, 1971, the NPS published in the Federal Register (36 FR 25406) a final rule to give notice that the name “Environman” and an Environman symbol named “Human Figure and Design” were owned and protected by the US Government. No information has been found about the symbol’s designer.

The symbol identified the role of the NPS in promoting high-quality environmental education and represented and symbolized those activities. The "Human Figure and Design" and name "Enviroman" were used in connection with National Environmental Study Areas (NESA) and the NEED National Environmental Education Landmark (NEEL) programs. NESAs were identified by a "Human Figure and Design" sign.

One newspaper article from January 16, 1972, described the symbol as “a stylized figure of a man within concentric lines indicating man in an environment of both conflicting and harmonizing elements which affect and are affected by man.”

The regulation provided the necessary protection of the symbol from unauthorized use, while listing guidelines for individuals wishing a license to reproduce, manufacture, sell, or use either “Environman” or the “Human Figure and Design.”

National Environmental Study Areas (NESAs)

The 1970 Environmental Education Act required planning for “outdoor ecological study centers.” This became the NESA program, a cooperative effort between bureaus in the Department of the Interior (like the NPS); Department of Health, Education, and Welfare’s Office of Education; National Education Association; and local communities. Environmental Study Areas (ESAs) used material developed by the NPS together with the existing curricula of participating schools. Teachers determined how best to use the materials provided by the NPS in their daily classes.

The program intended to help children relate to their world by:

-

Introducing them to their total environment—cultural and natural, past and present

-

Developing in them an understanding of how man uses his resources

-

Equipping them to be responsible and active members of the world they are shaping and being shaped by

NESAs were physical locations where students could apply their classroom learning. They could be primarily natural or cultural sites. Hartzog’s goal was “to see a study area within easy driving time of every school in the United States and full acceptance of the concept by our schools and communities that environmental education and awareness are vital to our society and its future.”

By 1971 the Washington, DC, Board of Education was using Catoctin Mountain Park as a year-round environmental education laboratory. About 1,200 fifth graders spent five days living in former Job Corps dormitories. Half of each school day was spent studying outdoors.

EXPAND

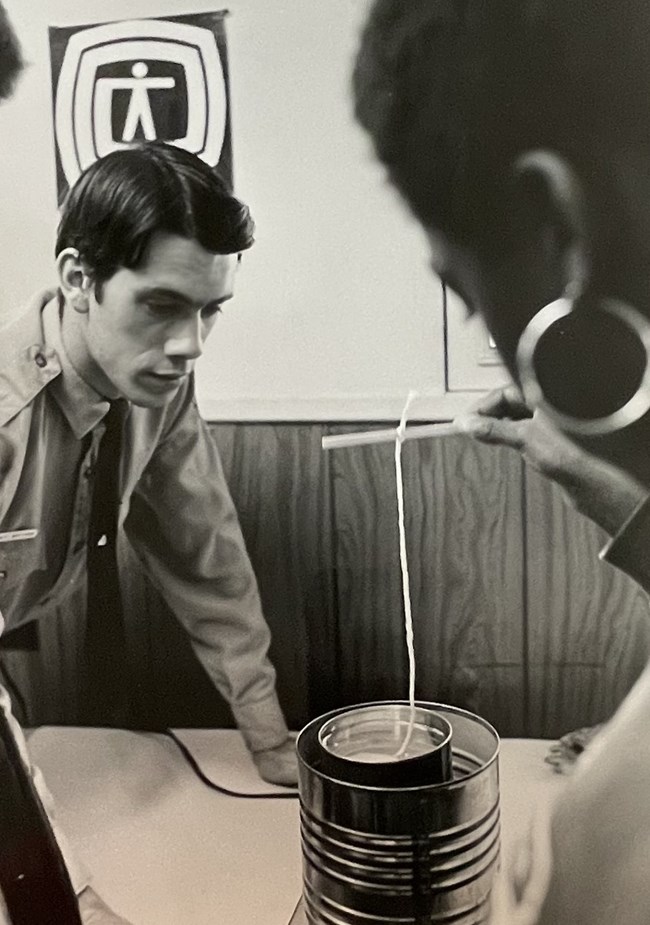

Another program created in 1970 was EXPAND. Designed and directed by NPS interpreter Marley Thomas, the program was an open-ended curriculum for urban environmental education. It evolved out of a need seen by NPS National Capital Parks Relations Specialist Maxine Boyd, Marley, and teachers in the Anacostia area of Washington, DC.

EXPAND was created as a three-week program to engage children in telling the story of their community. Available materials included felt boards, silkscreen posters, slide presentations, and filmstrips that addressed urban problems, stimulated discussions of how to solve them, and emphasized people’s relationships to the environment. Poetry, mime, music, theater, games, creative movements, and improvisations were also part of the program. Activities included landscaping their schools and neighborhoods using felt boards, studying ecosystems, and even making bread and churning butter.

In 1972 EXPAND was chosen as a feature on the NBC Today Show’s program focused on the NPS centennial of Yellowstone National Park. By 1973 over 24,000 children in the Anacostia area experienced EXPAND. In 1974 it expanded into two more areas in Washington, DC, in advance of citywide participation in advance of the Bicentennial.

National Environmental Education Landmark (NEEL)

In 1971 the NEEL program was created to recognize outstanding NESAs and helped local and state governments, citizen organizations, and private individuals:

- Identify and preserve nationally significant environmental study areas where students and others could participate in quality environmental education programs

- Encourage statement of an environmental ethic as the standard for personal and corporate conduct in the search for quality in daily life for an increasingly urban society

- Maintain a register of NEELs as a national inventory and reference for groups and individuals interested in exemplary environmental education programs

- Provide technical assistance to groups and educational organizations interested in developing environmental education programs.

NEEL sites could be publicly or privately owned so long as they possessed “natural or cultural resources of outstanding significance in illustrating the American environment as it is affected by and as it affects modern man.” Sites meeting the criteria were submitted to the Secretary of the Interior’s Advisory Board on National Parks, Historic Sites, Buildings, and Monuments, which made recommendations for approval. The secretary had final responsibility for designating national landmarks.

Students Towards Environmental Participation (STEP)

From the beginning, NPS regions and parks were encouraged to develop new approaches to environmental education. In 1971 staff at Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield (which became an ESA in 1969) sent 35 students to the Fifteenth Conference on Environmental Education sponsored by United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in Atlanta, Georgia. Those students developed the STEP program to encourage their peers to become environmental advocates in their own communities.

In 1972 STEP was added as another component of the NPS environmental education program. It was an environmental awareness-action program for high school students, assisted by the NPS, which offered workshops to teach them to be outdoor education leaders. Trained students organized clubs at their schools and built area-wide and regional STEP organizations ready to work with younger children through ESAs. Some also trained teachers to use outdoor classrooms and pushed for environmental reforms in their schools and communities.

Many states offered grants for their activities. Students worked in a variety of locations, including community and state parks. STEP students in national parks worked through the Volunteers-in-Parks program. By 1977 the STEP program had been adopted in 22 states. The end of NPS involvement in the STEP program isn’t well defined, although it was still hosting training workshops in some areas in 1978. At least one student from a STEP club still worked at Everglades National Park in 1984.

Envirovan

On May 12, 1971, Secretary of the Interior Rogers C. B. Morton dedicated the NPS Envirovan as a mobile nature center. The NPS spent $40,000 to convert a motor home measuring 12 by 60 feet and weighing eight tons. It was named by 11-year-old Marian Whittaker, a sixth-grade student from LaSalle Elementary School in Washington, DC. Her first-prize award for winning the naming contest was a new bicycle.

Naturalist Dean Clark Einwalter created and ran the Envirovan program for the NPS. The van’s exterior was painted with yellow, orange, and blue murals of city and country life. It accommodated 35 students at a time for programs that lasted about 45 minutes each. Primarily designed for students, it could also be used by adult groups. In summer it was used as part of the National Capital Parks “Parks for All Seasons” program.

The van carried 20 displays on natural history and the environment. Children handled live rabbits, turtles, lizards, snails, and snakes. The exhibits were designed to help children understand the “web of life” and their relationship to their environment through direct participation. The van carried supplies and exploratory equipment like water-testing kits, weather gauges, hand lenses, field manuals, and more to “stimulate investigation of a park’s biophysical resources” and “increase environmental sensitivity.” Envirovan visited dozens of schools in its first month. In June and July 1971 about 6,000 visitors per week visited it near the Washington Monument.

Similar envirovan programs were created outside the NPS with grants from the US Department of Education. The NPS Envirovan was difficult to move through the streets of Washington, DC and expensive to run as a vehicle. Around 1979 or 1980 it was moved to the east side of Rock Creek Park. Ron Crawford and Laurie Pope worked as the envirovan naturalists until it was removed from the park in 1983. It’s not clear what happened to the vehicle when the program ended.

Noah's Park

In August 1971 the NPS acquired LV116 Chesapeake, a former US Coast Guard lightship (a floating aid to navigation) launched in 1930. The 133-foot ship spent a year in rehabilitation at the Baltimore Shipyards and the Washington Navy Yards. During that time, NPS interpreters, volunteers, and teachers worked together to turn it into a floating environmental education facility promoting the understanding of water as a precious natural resource. The ship’s red color and red light served “to warn that man’s fragile environment is being threatened by pollution.”

Nicknamed “Noah’s Park,” the ship relaunched in fall 1972 and moved to her permanent mooring facility off East Potomac Park in the Washington Channel. The NPS created a bright yellow brochure (with red text) to advertise the program.

Children from Washington-area schools went aboard each weekday. The lightship was equipped with several aquariums and an environmental laboratory to study marine life in the Potomac Watershed area. STEP students used the lightship as an ESA to study marine biology, marshland community relationships, and water quality. College students from Georgetown University, American University, the University of Maryland, and Washington Technical Institute used the lightship for independent environmental education and ecology projects.

The ship was open to the public on weekends. Twenty-tree Sea Explorers used Chesapeake as their homebase for their scouting program. They spent weekends and holidays serving as her crew, learning skills such as welding, navigation, and electronics. The Sea Explorers also interpreted the lives and duties of the historic crew for the public as part of a living history program. Over 87,000 “visitor hours” were logged on the ship in fiscal year 1973. More than 8,000 students participated in the program between December 1971 and June 1974.

Chesapeake was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on August 1, 1980. In 1982 the NPS loaned her to the city of Baltimore, Maryland. In 1988 she became part of the Baltimore Maritime Museum. Chesapeake was designated a National Historic Landmark on November 20, 1989. The public can still visit Chesapeake at Historic Ships in Baltimore.

Towards the Centennial

As the NPS approached the 100th anniversary of Yellowstone, the first national park, in 1972, even greater emphasis was placed on environmental education. A new Division of Environmental Projects was established at the NPS Harpers Ferry Center. In May 1970 the division’s chief, Boyd Evison, created an environmental education task force to “evaluate existing environmental education programs and policies” and recommend “modifications and innovation, as necessary, to insure an effective environmental education effort by the Service.”

In 1972 a new NPS Office of Environmental Interpretation was established under Vernon “Tommy” Gilbert Jr. That office released National Environmental Study Areas: A Guide. Secretary of the Interior Rogers C.B. Morton wrote in the introduction,

In an age of growing environmental concern, the National Park Service areas find themselves as inevitable crossroads between educators and resource managers, places where the talents of each merge to form the basis for environmental awareness…Looking to the future, the importance of environmental education today is overwhelming. Without a growing public awareness and sensitivity, even the National Park System—set aside to preserve our natural and cultural heritage—will be in danger. As national parks and areas like them become more and more the focal point of an accumulation of societal concerns and ideas, they plead, even in a process of self-protection, that environmental education start now.

By September 1972 NEED instructional materials were available for teachers and students in grades three, four, five, and six. More than 90 NESAs had been set up within the NPS for schools to use as “outdoor classrooms.” Others had been established on other public and private lands. Sixteen NEELs had been designated. In 1972 the NPS designated the week beginning September 17 as Environmental Education Emphasis (EEE) Week. A newspaper headline asked, “Who will help Environman in triple E week?”

Environmental Living Program

In 1973 the NPS Western Region created the Environmental Living Program. It was a live-in, overnight experience for children in historic, prehistoric, or cultural sites. A 1975 brochure prepared by the NPS and the American Revolution Bicentennial Administration explained the program, which included a kit of four booklets and a poster.

A July 1976 brochure on NPS environmental education declared “Environmental education is a part of our lives that is here to stay” and explained that the Environmental Living Program “attempts to create a deeper understanding of today’s environments by providing opportunities for students to recreate environments of the past and then compare the two.” After classroom preparation, students played out the roles of Americans in former years at selected historic sites where these earlier Americans lived and worked. This program was available to all academic grade levels.

Declining Support

Portions of the NPS environmental education program never materialized as Hartzog and his staff envisioned. When Hartzog was fired by President Nixon in December 1972, the program lost its biggest advocate. Some have argued that it was the run-up to the Bicentennial of the American Revolution in 1976 that caused NPS educational priorities to change. The EXPAND and Environmental Living Program are evidence that the environmental education program and bicentennial program overlapped and engaged each other.

Others argued that the programs were ahead of their time, noting that most schools in the early 1970s didn’t have environmental education as part of their curricula and most teachers had no training in environmental studies. However, that suggests schools weren’t interested despite evidence to the contrary and ignores the successes of what had been implemented. By the end of 1977 there were 127 NESAs in parks and 53 outside of them. In 1976 over 400,000 teachers and students participated in NESA and other NPS-led environmental education programs. Another 5,000 teachers attended workshops to gain knowledge of environmental education skills and concepts.

It seems reasonable, therefore, to examine the lack of political will as a root cause. For his part, Hartzog recalled in a 2005 oral history interview that the NPS “had no interest in it after I left [in 1972] and abandoned the program.” He called that decision “ridiculous.” In truth, environmental education programs did continue in the mid- to late 1970s, but with less support. In 1974 the NPS Pacific Northwest Region created an educational message to attach to the Environman pins shown above when they were given away. The green cards featured the Environman logo, NPS arrowhead, and Department of the Interior seal. The primary message was “you are linked to the web of life. Everything you do affects it. Everything it does affects you. Man is directly connected to his environment.” The back of the card included tips for safely enjoying wilderness.

Ronald H. Walker, Hartzog’s successor, didn’t share his enthusiasm for environmental education. Others in key positions felt that traditional interpretation had suffered while Hartzog’s attention was on environmental education. In a 1973 oral history interview, Wayne Bryant, chief of the Branch of Visitor Services within the Division of Interpretation, expressed his opinion about environmental education this way:

These programs are fine, and I think it is great to have them. But these programs need equal treatment with our ongoing program rather than necessarily being over-emphasized, pushing that at the expense of the ongoing park program.

In addition, not everyone appreciated the system-wide approach, believing that historic sites should have been left out of the NEED program.

With Hartzog’s departure, the NPS Washington Office didn’t promote environmental education and eventually eliminated the environmental education program office. Many parks continued their environmental education programs, however, and the National Park Foundation remained committed to publishing NEED curriculum materials for K–2 and fifth grade.

Despite the shift of thought among NPS managers, as late as 1979 Assistant Secretary of the Interior Robert L. Herbst declared environmental education “an essential management function for every park.” However, as budget cuts and concerns about meeting traditional interpretive responsibilities took hold in the early 1980s, NPS Director Russell E. Dickenson endorsed and circulated a paper that frowned on programs not directly based on park resources or extended too far beyond them. Author Vernon Dame noted, “These can be exciting programs, but our job is to interpret the resources and themes of our parks, not to function as subject matter educators or as spokespeople for special causes.” The Department of the Interior issued a moratorium on all but mandated outreach programs.

On September 4, 1996, the NPS removed the regulations protecting the Environman symbol and program, citing that the symbol hadn’t been used since the early 1970s.

From NEED to Climate Change Education

The legacies of Hartzog’s environmental education efforts echo through continuing environmental education programs like those at Everglades National Park and the various educational programs created since the NPS launched its "Parks as Classrooms" program in 1991.

In many ways, however, it's the NPS National Climate Change Interpretation and Education Strategy, published in 2016, that is the successor to Hartzog’s concerns of 50 years earlier. He too argued that “the time to act is now.” Indeed, the strategy’s conviction that “All national parks are places to learn about climate change, discover connections between climate change and our own lives, and use this experience to make informed personal decisions” could have been written by Hartzog himself.

Sources:

--. (1968, April 4). “Director Announces Educational Program.” National Park Service Newsletter, Vol. 3, No. 7, p. 1.

--. (1970, February 19). “Education for Survival.” National Park Service Newsletter, Vol. 5, No. 4, pp. 1, 4.

--. (1971, August 29). “Secrets of Life Exhibited Wheels in DC Area.” The News Observer (Raleigh, North Carolina), p. V-7.

--. (1971, September 10). “EnvironVan Talks Here.” The Daily Herald (Chicago, Illinois), p. 9.

--. (1972, January 16). “’Environman’ Symbol Used for Education.” Rapid City Journal (Rapid City, South Dakota), p. 29.

--. (1972, September 17). “Who Will Help Environman in Triple E Week?” The Post-Crescent (Appleton, Wisconsin), pg. 57.

--. (1974, June). “Interpreting Noah’s Park.” In Touch, No. 2, pp. 8-10. National Park Service, Washington, DC. NPS History Collection (HFCA 1645).

--. (2022, April 3). “Einwalter, Dean Clark.” Star Tribune. Available online at https://www.startribune.com/obituaries/detail/0000421693/

Bryant, Wayne W. (1973, April 20). Interview with William T. Ingersoll. NPS Oral History Collection (HFCA 1817), NPS History Collection, Hapers Ferry, WV.

De Jong, Neil. (1995). “Children are the Future of the Everglades.” Interpretation, Summer 1995, pp. 27-30. Available online at http://npshistory.com/newsletters/interpretation/education-summer-1995.pdf

Dixon, Audry H. (1977, December 30). “National Park Service.” Environmental Education Activities of Federal Agencies.”

Hughs, Daniel S. (1973, March 5). “EXPAND.” NPS Newsletter, Vol. 8, No. 4. NPS History Collection (HFCA 1645).

Everhart, Bill. (1967, December 15). “The New Interpretive Lineup.” NPS Interpreters’ Newsletter, No. 3, pp. 1-2. NPS History Collection (HFCA 1645).

Horn, B. Ray. (1971, April). “Creating Environmental Awareness.” Trends, Vol. 8, No. 2. National Park Service, Washington, DC.

Huggins, Bob. (1995). “Education in the National Parks: A Servicewide Strategy.” Interpretation, Summer 1995, pp. 2-4. Available online at http://npshistory.com/newsletters/interpretation/education-summer-1995.pdf

Lee, Ronald F. (1972). Family Tree of the National Park System. National Park Service, Washington, DC. Available online at https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/lee2/index.htm

Lewis, Jeanine. (1978, September 13). “PATE, STEP Gaining Awareness of the Environment.” The Atlanta Journal (Atlanta, Georgia), p. 7.

National Park Service. (1976, July). Environmental Education in the National Park Service. NPS Division of Interpretation, Washington, DC.

Schull, Carol D. (1993). “Creating a Partnership.” CRM, Vol. 16, No. 2, pp. 4-5. Available online at http://npshistory.com/newsletters/crm/crm-v16n2.pdf

Pitcaithley, Dwight T. (2002). National Parks and Education: The First 20 Years. Available online at http://npshistory.com/publications/education/index.htm

US Bureau of Outdoor Recreation. (1971, April-May). “Department of the Interior.” Outdoor Recreation Action, No. 19, pp. 19-22. Washington, DC.

Tags

- catoctin mountain park

- kings mountain national military park

- lincoln boyhood national memorial

- national capital parks-east

- prince william forest park

- nps history collection

- nps history

- hfc

- conservation education

- environmental education

- george hartzog

- need

- nesa

- climate change education

- human impact

- childrens activity

- childrens history

- childrens program

- logo

- environman

- historic ship