Last updated: June 1, 2023

Article

50 Nifty Finds #26: Racing Bulldozers

A Resume of the Builder's Art

The Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) began in 1933 to document America's architectural heritage. Although the American Institute of Architects (AIA) endorsed the idea of “securing records of structures of historic interest” in 1918, it was President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal that provided the resources to do it. On November 8, 1933, President Roosevelt created the Civil Works Administration (CWA) and called for federal agencies to submit proposals for short-term initiatives. The proposal submitted by NPS architects Charles E. Peterson and Alston G. Guttersen through the Department of the Interior (DOI), noted,

Our architectural heritage of buildings from the last four centuries diminishes at an alarming rate. The ravages of fire and the natural elements, together with the demolition and alterations caused by real estate "improvements" form an inexorable tide of destruction destined to wipe out the great majority of the buildings which knew the beginning and first flourish of the nation. The comparatively few structures which can be saved by extraordinary effort and presented as exhibition houses and museums or altered and used for residences or minor commercial uses comprise only a minor percentage of the interesting and important architectural specimens which remains from the old days. It is the responsibility of the American people that if the great number of our antique buildings must disappear through economic causes, they should not pass into unrecorded oblivion.

HABS was established a month later, on December 12, 1933. It was the nation's first federal preservation program and the only New Deal initiative related to historic architecture. Its goal was to document "a complete resume of the builder's art," from outhouses to grand monuments and everything in between. Peterson’s boss Thomas C. Vint and architect John O’Neill oversaw the new program. The original proposal outlined a $448,000 program to provide work to 1,000 architects for four months. The program was approved by the Federal Relief Administration on December 1. By mid-January 1934 HABS employed 772 people.

On January 18, 1934, the CWA ordered that no new persons could be hired. Beginning February 15, programs were to begin shutting down with a 10 percent reduction each week. CWA funding ended on May 1, 1934. Only $196,267.63 of the appropriated $448,000 was spent. Before the program ran out, the NPS entered into a tripartite agreement with the Library of Congress and AIA to make the program permanent. Under this agreement, which is still in effect today, the NPS plans and administers the program and develops qualitative standards, organizes projects, and selects subjects for recording. The Library of Congress preserves the records, making them available for study. The AIA provides professional counsel.

Although the CWA ended, other relief programs provided funding to continue HABS work through the states in 1934 and 1935. The administrative burden at the national level to support the state projects was offset by Public Works Administration funding in 1934 and 1936. By the end of 1934, HABS had produced over 5,000 sheets of measured drawings and over 3,000 photographs.

HABS provided a working model and tested field documentation strategies that influenced passage of the Historic Sites Act in 1935. As first attempted by HABS, an important aspect of the act was "a thorough survey of all historic sites in this country." The NPS Branch of Historic Sites and Buildings was assigned responsibility for implementing most of the act's requirements. HABS fulfilled the section of the law that required the secretary of the Interior to document historic sites.

Between 1934 and 1942, HABS documented 7,000 historic structures on index cards. Half were photographed; one-third were drawn and measured. In some cases, written reports were prepared as well. World War II brought an end to funding and labor for most architectural surveys. The NPS was largely in a holding pattern during the war as men like Peterson (US Navy, 1941–46) joined the war effort. The HABS program was maintained into the mid-1950s by donations to the collection, particularly by former HABS district officers and by NPS-initiated recording projects. The post-war years would bring new threats, opportunities, and leadership at a crucial period for historic architecture in the United States.

HABS Restored

Peterson returned to the NPS after the war, becoming resident architect at Independence National Historical Park in 1950. During the Depression unemployed architects and draftsmen had been readily available. The construction boom after World War II made it much harder to hire professional architects. As a result, Peterson began a student internship program at Independence in 1950. Many of those students went on to architectural careers in the NPS and elsewhere. One—James C. Massey—would become chief of HABS.

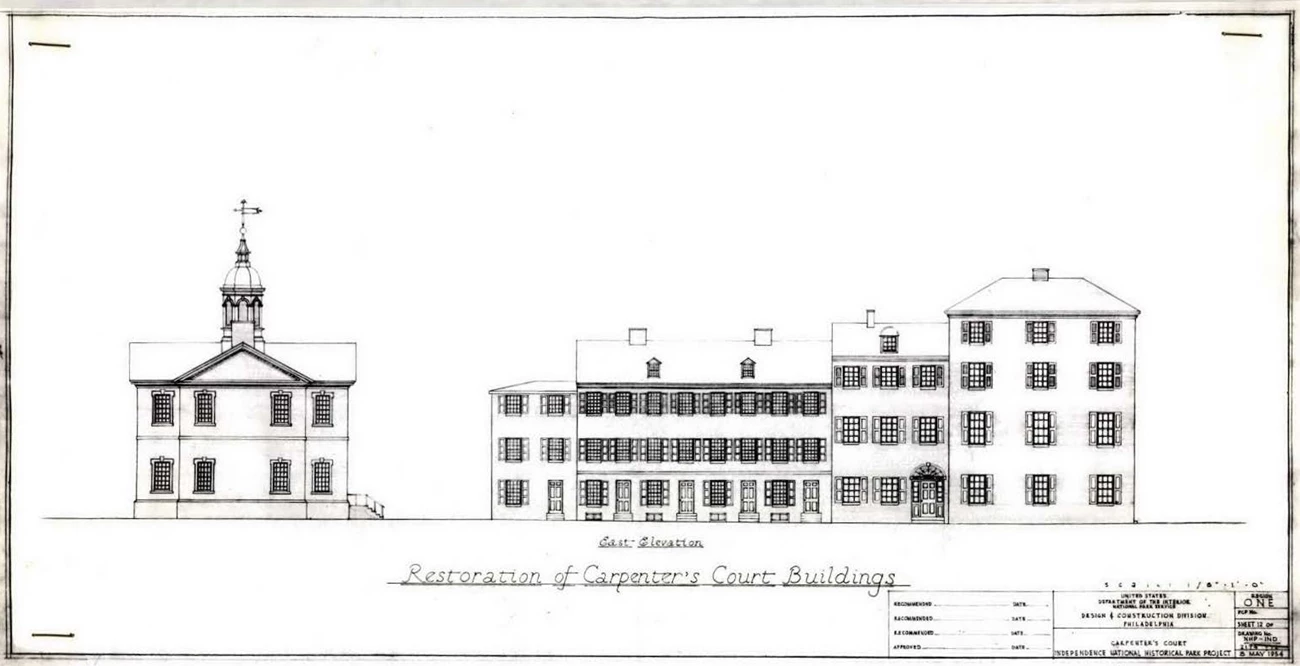

James Carlton Massey’s NPS career began in 1953 as a 21-year-old student architect at Independence. He studied Carpenters’ Court to identify the court's original buildings, what remained of them, and their historic appearance. He continued work begun by Peterson, who oversaw his efforts. Massey also prepared the drawings to reconstruct the exterior appearance of the buildings on the court. He later recalled working with Peterson in 1953 as “a rich and heady experience that defined my architectural career.” Massey completed his work on Carpenters' Court during the summer of 1954. After earning an undergraduate degree in architecture from the University of Pennsylvania in 1955, he got a temporary job as a historic architect at the Eastern Office of Design and Construction (EODC) established by the NPS in Philadelphia in 1954.

On November 5, 1955, he married Anne Elizabeth McLaughlin, an interior designer. He resigned from the NPS in January 1956 to join the US Army. He served for two years with the Office of Military History in Karlsruhe, Germany. During that period, the Masseys traveled in Europe whenever they could, expanding their knowledge and appreciation of historical architecture.

After the EODC formed, Peterson became its supervising architect for historic structures. In 1956 the NPS began Mission 66, a 10-year program to improve its facilities. Although it focused on construction of new visitor centers and other park infrastructure, it also funded the preservation and rehabilitation of historic structures, particularly in new or proposed NPS units. In 1958 HABS became a "continuing program under Mission 66 with accelerated workload in later years. It [was] resumed concurrently with the National Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings, and there will be some cooperative enterprise where the two will be working together."

Sharing his "thoughts about the proposed HABS program" in a May 24, 1957, memo, Peterson noted:

I do not believe it will be very soon possible to rally the number of competent architects to work on HABS that we had in 1933 and afterwards. I believe that at least 50% of the money should be expended on first-class professional standard photographs, supplemented in many cases by floorplans and a limited number of other drawings.

In 1958 Department of the Interior appropriations included $116,000 for HABS. That same year Jack E. Boucher became the first full-time, professional photographer regularly employed by HABS. Boucher set the standards for photography and creating archival prints and negatives for the HABS program.

Massey returned to the United States in 1958 shortly after HABS was reactivated. He was rehired as a historical architect at the EODC, where for the next four years he conducted research and carried out restoration projects for historic buildings in national parks. Because HABS had more money than staff, Peterson pulled Massey into HABS work whenever possible.

The Cold War briefly resulted in a change of priorities from most at-risk buildings to those that were deemed nationally significant. HABS's 1958 specifications noted,

The unprecedented and indiscriminate destruction wrought abroad [since 1939] has brought realization that, should this country be attacked, well within the realm of possibility, some of these heritages from our past might be lost. In order to make possible the authentic restoration or reproduction of these buildings, if damaged or destroyed, measured drawings, photographic and other records should be prepared without delay.

A Desperate Time

By 1961 the risk of nuclear attack was less pressing than the internal threats created by the post-war construction boom, urban renewal, highway and dam construction, and suburban development. Historic structures were being lost at an alarming rate—and faster than HABS and other preservation organizations could document them. Sometimes HABS personnel literally worked with bulldozers humming in the background, ready tear down the buildings in the name of progress. In 1963 Massey, Boucher, and student intern John Milner were given four hours to document President Ulysses S. Grant’s summer cottage in Long Branch, New York, before it was destroyed to create a parking lot. Massey later recalled that period saying, "It was a pretty desperate time. Things were being torn down wholesale, blocks at a time and square miles at a time. We were running round trying to photograph and document buildings of some consequence that were about to be torn down."

The NPS was also tearing down some of its historic buildings. Peterson was particularly disturbed by losses at Independence, where the NPS demolished buildings to create Independence Park. Massey later recalled, "[HABS] went around recording buildings as cultural documents which the Park Service would then turn around and demolish. We were viewed rather awkwardly by a lot of Design and Construction [staff]." Frustrated with what he perceived as a lack of support for historic structures work in the NPS, Peterson retired in October 1962 to pursue a career in the private sector. Massey became supervisory architect for HABS, responsible for surveys in the eastern United States. In 1964 the HABS building-age criterion was reduced again, this time to buildings more than 50 years old.

According to Masseys' March 1965 resume in the NPS History Collection, he still held that position three years later. At that time, probably due to plans to reorganize the NPS and replace the design and construction centers with new service centers, he sought and received an interview with the Urban Renewal Administration. In a May 28, 1965, introductory letter to them, he described his job at the time:

In my work with HABS I have been responsible for the selection and arrangement of recording projects, which are largely carried on in cooperation with historical societies, preservation groups, and state and local governments. In addition, my work has included organization of exhibitions, public speaking, and budget matters, as well as the supervision of the HABS staff. This work has given me a wide personal acquaintance with people and organizations involved with architectural history and historic preservation.

In December 1965, staff received notice that the NPS eastern and western regional offices of design and construction would be closed. The December 18, 1965, letter to Massey from Director George B. Hartzog, Jr. stated, "After careful screening, I have selected you to serve in the Service Center in Washington where you will continue to perform the same duties at your present grade without change in [your supervisory architect] title.

The EODC was replaced by the new Philadelphia Service Center. The HABS operations in Philadelphia were ordered to the new Washington Service Center in Arlington, Virginia. Massey and other HABS architects were to enter on duty in Washington on March 13, 1966. Massey's date was pushed back to July 3, 1966. He ultimately arrived in August of that year. Massey’s article “Preservation Through Documentation,” published in Historic Preservation (July/August, 1966) discussed the long-standing HABS policy to prioritize about-to-be-destroyed buildings. The title was the first printed use of the phrase that became a motto of sorts for HABS’s mission.

Although 1966 is usually cited as the year that Massey became chief of HABS, Hartzog's memo and other events suggest it was the next year before it became effective in practice. Massey took a leave of absence from the NPS from September 1966 to February 1967 when he received a research grant from the Ford Foundation that involved an extended stay in Europe. Although he may have accepted an offer of HABS chief in 1966, it seems unlikely that he functioned as such during that period.

In 1965 President Lyndon B. Johnson had convened a special committee on historic preservation. The committee's report, With Heritage So Rich, noted that HABS had documented 12,000 places in the United States. By 1966 half of them had either been destroyed or damaged beyond repair. The report described the HABS collection as "a death mask of America." This report led to passage of the National Historic Preservation Act on October 15, 1966.

Among other things, the new law gave the NPS a lead role in documentation and preservation and created the National Register for Historic Places. In 1967 the NPS created the Office of Archaeology and Historic Preservation (OAHP), under the direction of Ernest Connally, to carry out the programs. HABS became part of OAHP’s new division of historic architecture. The January 6, 1967, organization chart for the new office lists Massey in charge of the "surveys branch." His return to the NPS in early March 1967 after the leave of absence probably reflects when he began functioning as HABS chief.

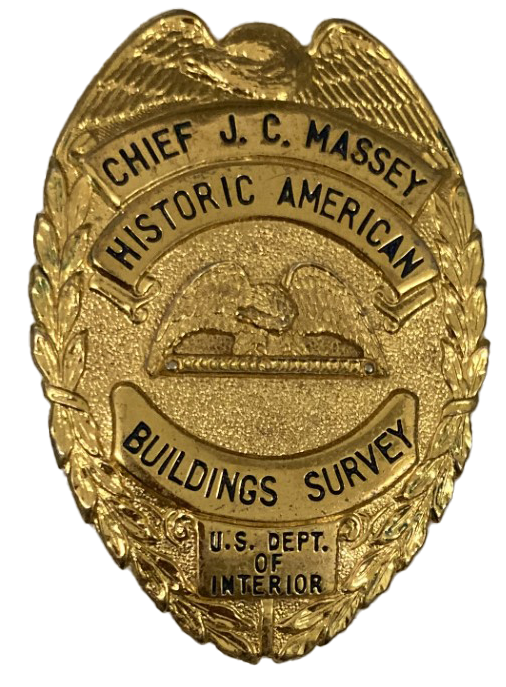

As chief, Massey had an official badge, which is now part of the NPS History Collection. Given that he didn’t have legal or regulatory authority as chief, it’s assumed that the badge was for identification purposes only—but it probably didn’t hurt to have it when negotiating to hold off the bulldozers a bit longer. It's also interesting to note that the badge references the Department of the Interior rather than the NPS.

In 1969 Massey facilitated creation of the Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) as a sister program to HABS. HAER documents the industrial and engineered components of America's built environment. On April 14, 1970, Massey received the Department of the Interior’s Meritorious Service Award from NPS Director George B. Hartzog Jr. for “his outstanding career in the field of historic architecture.”

Massey left HABS in 1972. John Poppeliers, who joined HABS as a historian and editor in 1962, served as director from 1972 until 1980. Future HABS chiefs would include Robert J. Kapsch, Kenneth L. Anderson, Paul Dolinsky, and Catherine Lavoie. In 2001 the Historic American Landscape Survey (HALS) became another sister program to HABS.

Massey continued to be a leader in the preservation of historic architecture. After leaving the NPS, he was vice president of historic properties for the National Trust for Historic Preservation for nearly 10 years, including the crucial bicentennial period. In 1980 he and Constance Werner Ramirez co-founded the non-profit National Preservation Institute (NPI) to provide a consistent schedule of training by preservation professionals. In 1983 Massey and his second wife Shirley Maxwell formed the preservation consulting firm Massey Maxwell Associates. In 1989 Massey earned a master of planning degree from the University of Virginia. He also taught as an adjunct professor, was president of the Historic House Association of America, and served on planning commissions and architectural review boards in his Virginia communities.

Throughout his career Massey wrote many architectural history articles, manuals for architectural surveys, exhibit catalogs, and books. He was also a sought-after guest speaker and lecturer. Massey and Maxwell’s books include Gothic Revival (1995), Arts and Crafts (1995), House Styles in America: The Old House Journal Guide to American Houses (1996) and Arts and Crafts Design in America: A State-by-State Guide (1998). He was a contributing editor and regular contributor to The Old-House Journal for 20 years.

Massey died November 10, 2021, at his home near Winchester, Virginia. He was 89 years old.

Learn more about HABS and its sister programs at NPS Heritage Documentation Programs or search the Library of Congress’ HABS database to see drawings and photographs of over 43,000 structures and sites documented in the 100 years since HABS was created.

Sources:

--. (1955, October 30). “West Phila.” The Philadelphia Inquirer (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), p. 14C.

--. (1966, February 16). “Support Urged for History Sites.” The Buffalo News (Buffalo, New York), p. 26.

--. (1970, April 30). “Morning Glory.” NPS Newsletter, Vol. 5, No. 9, p. 1-2.--. (2022, March 15). “James Massey.” Accessed May 25, 2023, at https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/washingtonpost/name/james-massey-obituary?id=33622821

--. (1972, May). “What’s Going On.” History News, Vol. 27, No. 5, p. 116. Accessed on May 27, 2023, at https://www.jstor.org/stable/42648046?searchText=%22James+C.+Massey%22+HABS&searchUri=%2Faction%2FdoBasicSearch%3FQuery%3D%2522James%2BC.%2BMassey%2522%2BHABS&ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_phrase_search%2Fcontrol&refreqid=fastly-default%3A0748d6a2a50bca4026cd7b1bdee62e5c

--. (2022, December 1). “National Historic Preservation Act.” Accessed May 28, 2023, at https://www.nps.gov/subjects/historicpreservation/national-historic-preservation-act.htm

Desk Files of James C. Massey. NPS History Collection (HFCA-02025), Harpers Ferry, WV.

Massey, James C. (1954, August). Carpenters’ Court. Revised Edition. NPS Eastern Office of Design and Construction. Accessed May 27, 2023, at https://irma.nps.gov/DataStore/DownloadFile/603938

Massey, James C. (2006). “In Memory of Charles E. Peterson, 1906-2004.” APT Bulletin: The Journal of Preservation Technology, Vol. 37, No 1, p. 4. Accessed May 27, 2023, at https://www.jstor.org/stable/40004675

Massey, James C., Schwartz, Nancy B., and Maxwell, Shirley, (1992). Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record: An Annotated Bibliography. National Park Service, Washington, DC. Available at npshistory.com/publications/habs-haer-hals/habs-haer-bibliography.pdf

Maynard, W. Barksdale. (2013). “A New Deal for Old Places.” Colonial Williamsburg Journal, Summer 2013. Accessed May 29, 2023, at https://research.colonialwilliamsburg.org/Foundation/journal/summer13/buildings.cfm

National Park Service, Department of the Interior, Library of Congress. (2008). American Place: The Historic American Buildings Survey at Seventy-five Years. Accessed May 26, 2023, at http://npshistory.com/publications/habs-haer-hals/american-place.pdf

National Preservation Institute post on James C. Massey’s death, accessed May 26, 2023, at https://www.linkedin.com/posts/national-preservation-institute_we-are-deeply-saddened-by-the-recent-passing-activity-6866718535876538368-jGn6/?trk=public_profile_like_view

Vider, Elise. (1991). The Historic American Buildings Survey in Philadelphia, 1950-1966: Shaping Postwar Preservation. Theses in historic preservation, University of Pennsylvania. Accessed May 27, 2023, at https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1317&context=hp_theses

Yearby, Jean P. (1984, January). “HABS’ 50th Anniversary.” Courier: The National Park Service Newsletter, Vol. 29, No. 1, pp. 1-2. Available at npshistory.com/newsletters/courier/courier-v29n1.pdf