Last updated: February 19, 2026

Article

50 Nifty Finds #18: Portable Posters

Many visitors to national parks today collect passport stamps, magnets, patches, t-shirts, and other memorabilia to recall their trip and to show others where they’ve been. In the 1920s and 1930s the “must-have” souvenirs weren’t created to be collected at all. National Park Service (NPS) windshield stickers served a practical administrative purpose: they were evidence that the automobile license fees due at some parks had been paid. As the NPS and politicians debated who should fund national parks and how, Americans embraced the stickers' colorful, artistic designs, sparking a collecting craze. Drivers pasted so many to their windshields, they quickly became a safety hazard. In the media, the NPS got the credit and the blame in the backlash against them and the fees they represented.

The First Visitor Fees

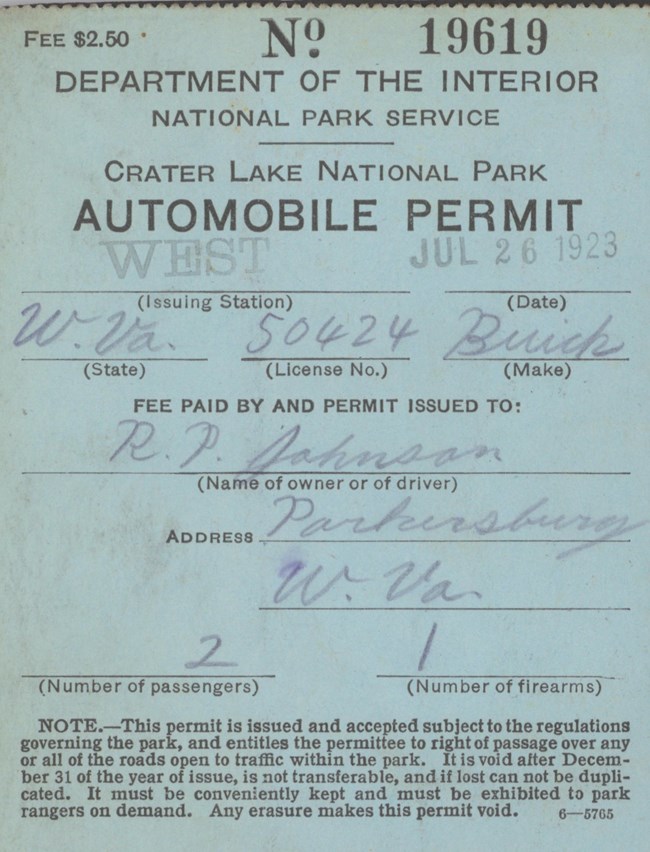

In 1908 Mount Rainier was the first national park to admit cars and charge a fee for use of the road. Two years later General Grant National Park did so, followed by Crater Lake (1911), Glacier (1912), Yosemite (1913), Sequoia (1913), Mesa Verde (1914), and Yellowstone (1915) national parks. In the early days of cars in national parks, the NPS based its automobile “license fee” on the miles of roads in the parks. It was the first fee charged to visitors by the NPS. Initially, visitors were given "tickets of passage" which were returned when they left the parks. Through 1916 either single trip or seasonal licenses could be purchased. Beginning in 1917 only seasonal licenses were available, but they were sold at the single trip rate. The fees varied from 50 cents at General Grant to $7.50 at Yellowstone and were set based on the miles of available roads. In parks where the government hadn’t undertaken any road improvements, no license fee was charged for driving over the existing roads, such as they were. Until June 30, 1917, all money raised from the license fees were placed in a special fund at the US Treasury Department for direct use for park development and administration without congressional appropriation. Starting July 1, 1918, the money went to Treasury’s general fund.

A windshield sticker (also historically called a paster, and today sometimes called a decal or stamp) was given to a driver along with a receipts for payment of the fee. They allowed rangers to see at a glance if a car had registered at an entrance station. In a 2011 article, collector Rusty Morse points out that the stickers were technically revenue stamps since they documented a tax or fee paid. Based on a photograph of one in a private collection, they were first used at Yosemite in 1917.

In 1917 and 1918 Yosemite windshield stickers were round, with the park name around the outer edge. The middle of the sticker included the date, park regulations such as the speed limit, and reminders to read signs, drive carefully, sound your horn, and other safety messages. The 1917 date corresponds to the change to seasonal license fees only. It's reasonable to assume, therefore, that they were used at all eight parks that charged automobile fees, even if examples haven't survived and their designs are unknown. A 1918 advertisement for a lost Brownie camera with a “Yosemite paster” would refer to one of these round windshield stickers.

The earliest known sticker from Yellowstone is also in a private collection and dates to 1918. Unlike the round Yosemite sticker, it was octagonal. The use of different sticker designs at two parks in the same year suggests that the NPS had not yet standardized the design. The Yellowstone sticker features the park name and year in the middle. Similar rules and safety notices to those on the Yosemite stickers are also present. Interesting features of the 1918 Yellowstone example are suggestions to "buy war saving stamps" and "buy thrift stamps," even as World War I was coming to a close.

Several 1923 newspaper articles give credit to Yosemite superintendent Washington B. "Dusty" Lewis for the idea of using the windshield stickers in the NPS. Lewis arrived at Yosemite in March 1916 as the park's supervisor and became superintendent on November 11, 1917. If they were Lewis’ idea, it would have had to come to him fairly quickly to get it implemented for the 1917 tourist season. However, necessity is the mother of invention and Lewis may have been led there by labor shortages due to World War I. Lewis was certainly an "out-of-the-box" thinker. He hired Clare Marie Hodges as Yosemite’s first woman ranger in 1918 when there weren't enough men to fill his ranger positions after the United States entered WWI. Windshield stickers that let a ranger tell at a glance if a fee had been paid could have offset fewer rangers at entrance stations or reduced entrance station hours. Although a WWI inspiration is a logical suggestion, no records have been found to support it.

Windshield stickers from 1919 for Yosemite, Yellowstone, and Mount Rainier are known from private collections. In addition, there is a photograph of one on the side of the first airplane to land in Yosemite Valley. The flight, considered "100 per cent dangerous," was completed by U.S. Army Lieutenant James S. Krull on May 27, 1919.

The 1919 stickers are only printed on one side. The front, with the park name, date, and safety information, became the back of the stickers when animal images were added to the front in 1920. The 1919 Yellowstone sticker a two-tone green and white (like the back of the 1921 Yellowstone sticker in the photo below but with the green half on the right). The 1919 Mount Rainier sticker looks the same as Yellowstone but is printed in red and white with the red half on the left.

The 1919 Yosemite sticker is different from the other surviving examples. It has a solid green field surrounded by a white border. None of the Yosemite stickers have the two-tone back. A May 31, 1919, Stockton Evening and Sunday Record article discusses the outcome of that year’s reliability race. The article reports:

The earliest examples of windshield stickers in the Yosemite and Yellowstone national park museum collections are from 1920. The earliest in the NPS History Collection is from 1921.

The Early Eight

Although some authors imply that 12 stickers were produced in the beginning, license fees were only charged in eight parks. Logically, stickers would have only been made for those eight parks. In 1920 the NPS standardized the windshield stickers look (for the most part), shape (sticking with the octagon), and size (five inches across). As noted above, what was the front in 1919 became the back, allowing the safety reminders and regulations to be read from inside the car. The front of each featured the park name, date, and a drawing of a native animal:

- Yellowstone (bison)

- Sequoia (elk or wapiti)

- General Grant (Columbian gray squirrel)

- Yosemite (mountain lion)

- Mount Rainier (Columbian black-tailed deer)

- Crater Lake (black bear)

- Mesa Verde (coyote)

- Glacier (mountain goat)

In 1920 no licenses were required for Wind Cave, Hot Springs, Platt (now Chickasaw National Recreation Area), Hawai'i, Lassen Volcanic, Sullys Hill (transferred to the US Department of Agriculture in 1931), Rocky Mountain, Grand Canyon, and Lafayette (now Acadia) national parks. In addition, no license fee was charged at national monuments or at Mount McKinley National Park (now Denali National Park & Preserve) because it had no roads.

The back of the sticker displayed the park name, "Department of the Interior" and "National Park Service," and safety and resource protection messages that would be seen from inside the car, including:

- Keep out of the ruts.

- Horse-drawn vehicles have the right of way.

- Read and comply with the park rules. They are there for your guidance.

- Drive carefully and avoid accidents.

- Sound your horn.

- The speed limit

- The park is yours. Help us take care of it.

- [For Yellowstone] Writing or carving names or initials on geysers and hot spring formations is strictly prohibited.

Some of these are a reminder of how new cars were to national parks where roads were designed for horse-drawn vehicles.

The Fad Takes Off

The new design was popular during the 1920 tourist season. An article in the Stockton Evening and Sunday Record with the subheading “Study of Windshield Stickers” described a Pathfinder car that came through town:

It carries the windshield stickers of Glacier, Mt. Rainier, Crater [Lake], and Yellowstone national parks—or it did when it passed through Stockton. Ere these lines are perused by Record readers the stickers of Yosemite, General Grant, and Sequoia parks will have been added.

The windshield stickers aren’t mentioned in the NPS director’s annual reports until 1921. The report notes, “An appealing feature of our park travel is the annual large increase of private motor travel over that by all other means of transportation. Furthermore, the motorist seems not to be satisfied with a visit to one of the parks but must take in two or three. Sometimes even as many as a half dozen national park wind-shield stickers are to be seen on individual cars, attesting to a visit to that number of parks.”

In 1921 the Modesto Morning Herald ran an article with the headline “Gathering Park Permits Latest Fad for Motorists.” It noted, “Where the traveler in former days rejoiced in the number and variety of hotel stickers that he could accumulate on his luggage, the modern tourist prizes the number of national park permits that he can accumulate on the windshield of his car during a summer’s touring.”

Although the license fee and windshield sticker were for cars and motorcycles, Louise Yunker, Selma Miller, and Miriam Brooks, the first three visitors through the West Yellowstone entrance in May 1922, found it also applied to skis. A newspaper article noted,

If skis were vehicles and must carry licenses, just where, on each of the three pretty girl applicants, would a fellow paste the familiar license sticker which regulations required be placed on the windshield? Obviously the situation demanded a compromise, and so, when the first fair visitors of the gala golden anniversary year of Yellowstone passed thru the gateway of the park as forerunners of the thousands to follow, they were duly checked in and licensed—the green stickers that said so were jauntily pasted squarely between their shoulder blades.

A February 17, 1922, newspaper article encouraging people to visit the national parks noted, “Someday, [NPS Director Stephen] Mather believes, it will be as fashionable to have a windshield covered with stickers from the various parks as it used to be to have a suitcase plastered with European hotel labels.” The popularity of the windshield stickers was brought up at the 1922 National Parks Conference. The program listed a discussion topic of “automobile maps and windshield stickers.” Specific considerations were to be “what they should contain, their purpose, and value. The windshield sticker as an aid in the prevention of forest fires.” Unfortunately, the minutes from that meeting are not available. It seems reasonable to assume that one of the outcomes of the conference was a decision to make the stickers smaller because when the 1923 stickers came out, they were four inches across, rather than five.

Newspaper articles from 1923 report that stickers were also created for four more national parks: Grand Canyon (beaver), Rocky Mountain (bighorn ram), Wind Cave (antelope), and Zion (porcupine). However, surving examples in private collections show that Grand Canyon, Rocky Mountain, and Zion were using stickers as early as 1922. Interestingly, the NPS director's annual reports state that automobile license fees weren't required at Grand Canyon until 1925, Zion until 1926, and Wind Cave and Rocky Mountain until sometime after 1932 (later reports unavailable). In addition, a sticker for Lassen Volcanic (bobcat with volcano in the background) from 1925 is known from a private collection even though the director's reports indicates that the fee wasn't required there until 1929.

This disconnect between surviving windshield stickers and NPS records suggests an evolution in their use, but the issue needs further study.

The Plague of Pasters

The “trophy collecting” craze for these “portable posters” exploded in 1923. A March 19, 1923, editorial in the Cordova Daily Times titled, “Advertising National Parks,” noted that some parks ran out of them long before the end of the season. It also suggested that the "special pictorial zoo" was to be "the outstanding feature of the campaign of 1923 to sell to the American people the great playgrounds of the West." The author described the NPS windshield stickers as "an elaboration of the scheme of windshield advertising that has been finding itself this past couple of years."

The NPS received both the credit and the blame for the trend. A November 3, 1923, newspaper article noted, “Motorists on tour began to prize their stickers and, it is said, some make trips to parks as much for the purpose of acquiring a windshield trophy as to enjoy the attractions offered. All was well, as long as the use of stickers was restricted to national parks. But almost every resort, hotel, and community in the country seized upon the idea to gain advertising and the sticker craze ran riot.”

At the same time, newspapers began printing articles in backlash against what E. W. Gale Jr. called “Stickeritis” and the “Plague of Pasters.” Safety issues were raised as drivers couldn’t see out windshields covered with stickers. With tongue firmly in cheek, Gale suggested “the next models [of cars] will all be equipped with oversize windshields and have periscopes so that you may stick stickers to your heart’s content and still have some idea of your whereabouts.” Gale also suggested that the stickers were “creating a new caste in the country. A guy who has been to Yellowstone or Glacier national parks and has a paster to prove it won’t speak to a fellow who hasn’t anything better than a Yosemite label, and the Yosemite lad in turn won’t have anything to do with the possessor of a mere Big Bear sticker.”

The Long, Slow Goodbye

Following the 1923 tourist season, NPS Director Stephen T. Mather spoke on the issue of windshield stickers at the National Parks Conference held October 22–28, 1923, at Yellowstone National Park. The meeting minutes record,

In the past the sticker has been a splendid advertisement for the parks, but since the collection of wind-shield stickers has become a popular fad this year, and the stickers are being by summer resorts, hotels, and all sorts of places, with the result that the wind-shields of many automobiles are so covered as to impair visibility of the driver, [Mather] felt that they have to be abolished by the Park Service.

In the end, the conference decided to abolish the stickers. A committee made up of superintendents W. B. Lewis at Yosemite, Colonel John R. White at Sequoia, and Roger Toll at Rocky Mountain, was appointed to “look into this matter and make recommendations to the Washington Office as to what should be adopted to take the place of the sticker on the windshield.”

Newspaper articles quote Mather saying, “I suppose it will only be a question of time until the windshield sticker is legislated against. We may as well begin looking around for something to take its place.” They also noted that the committee was asked to come up with an idea that was “striking, original, and cheap in cost” to replace the individual park stickers with one that would apply at all national parks. One newspaper article suggested “some sort of metal insignia attached to the radiator,” but that idea was not new (having been used by others as early as 1919) and didn’t gain any traction.

It appears that the only recommendation that the committee came up with was to make the stickers smaller once again. On June 21, 1924, the NPS further reduced the size of the windshield stickers to three inches. One newspaper account noted, “The popularity of the sticker has increased so many fold as to constitute a nuisance in mountain driving where a wide range of vision is absolutely necessary.” Despite the recognized safety hazard, the NPS continued to their use another 15 years—and created a new Park to Park Highway windshield sticker in 1924.

Despite deciding to abolish it, the license fee continued to be an issue for the NPS. It was a hot topic at the 1925 National Parks Conference at Mesa Verde National Park. The meeting minutes give insight into the issues. Horace M. Albright, Yellowstone superintendent and NPS assistant director for field operations, noted:

Mr. Mather has gotten into this automobile fee controversy with the Motor West Magazine which has been pounding us pretty hard with vigorous editorials. It looks like more than one automobile magazine, and probably some of the automobile clubs, are going after it. The thing that got me thinking about it more than anything else was the interest that congressmen and senators were taking. Except Congressman Cramton, who thought we might make it a registration fee, they were all against this entrance fee. I think as a general rule people believe that the money is being expended on roads and I know, even though we carefully instruct our rangers to tell people that the money goes into the Treasury, the rangers adopt the easiest defense of the fee that they can and state that it goes to the roads. The fee, it seems to me, is going to be shot at a lot in the next few months.

Acknowledging that Yellowstone would “lose by far the most if it is taken off,” Albright advocated for removing the automobile fee. Others agreed, noting that federal funding had already paid for most of the roads visitors used, not all parks charged the fee, and toll roads in general were being phased out in the United States as the government built more roads. The cost of collecting fees, accounting for the money, and risk of robbery were also arguments raised against the automobile fee.

Assistant Director Arno B. Cammerer expressed the view, “As I have reviewed it, the feeling I have had is that the movement ought to come from the Department, and if Congress is willing to finish it, it ought to be up to them in the long run. The general feeling is that this is a direct tax, and something in the nature of recreation that the government is providing for people that should be free, and the President’s policy is to make a reduction in these.”

The windshield stickers remained.

A Taxing Situation

Try as it might, the NPS couldn’t seem to do away with the automobile fee and the accompanying stickers. Competing interests in Congress, concerns of the Budget Office, and different philosophies about who should pay to support national parks all kept Congress from "finishing it." The NPS reduced the license fee in 1926 as the number of cars entering national parks continued to increase.

In 1928 Representative Louis C. Cramton of Michigan, chairman of the Interior subcommittee of the House Appropriations Committee, proposed a seasonal pass that would admit a car to all national parks "for one or two dollars" and focus on "visitor control only rather than generating revenue." Cramton's attempt to legislate a single seasonal pass, which wasn't supported by the NPS, failed.

Bryce Canyon and Grand Teton began requiring licenses in 1929. The earliest known surviving examples are 1930 for Bryce Canyon (hoodoo scene) and 1932 for Grand Teton (mountain scene). In 1930 the text on the back of the stickers was simplified as the size no longer allowed for detailed safety information. In addition to the park name, year, "National Park Service," and "Department of the Interior," they note "safety first" and direct the driver to "read and observe the regulations."

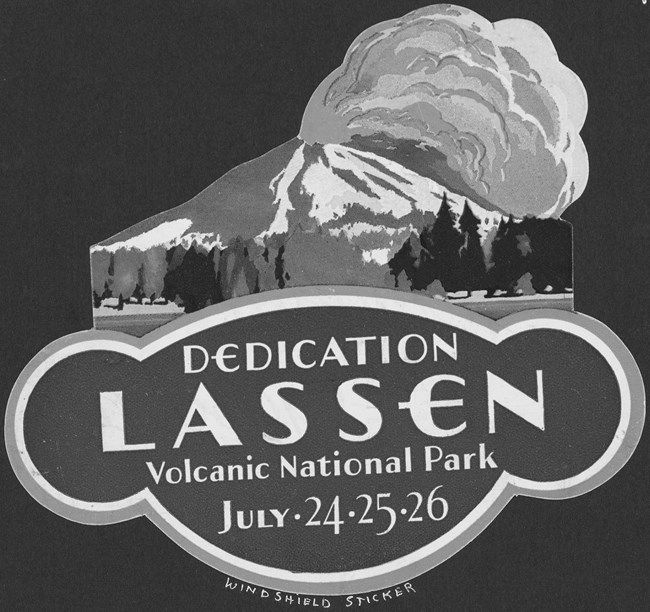

The September 1932 Park Service Bulletin reported that "for the first time in its history Hot Springs National Park has an automobile sticker." The article notes that the sticker was "approved for advertising purposes" and began distribution in July 1932. At least two special edition windshield stickers are known to exist; both were created in 1931. The Colonial National Historical Park sticker, in a private collection, commemorates the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Yorktown. The Lassen Volcanic sticker was created to celebrate the park's formal dedication following completion of the main park road. Given that the $1.00 automobile entrance fee was suspended during the dedication events, this sticker had a commemorative function rather than an administrative one.

President Roosevelt’s 1935 budget instructed the NPS to develop a fee structure for all national parks and monuments. The money raised was to go towards making the NPS more self-sustaining. As a result, automobile fees and windshield stickers for more parks were added, including:

- Acadia (seashore scene) by 1935

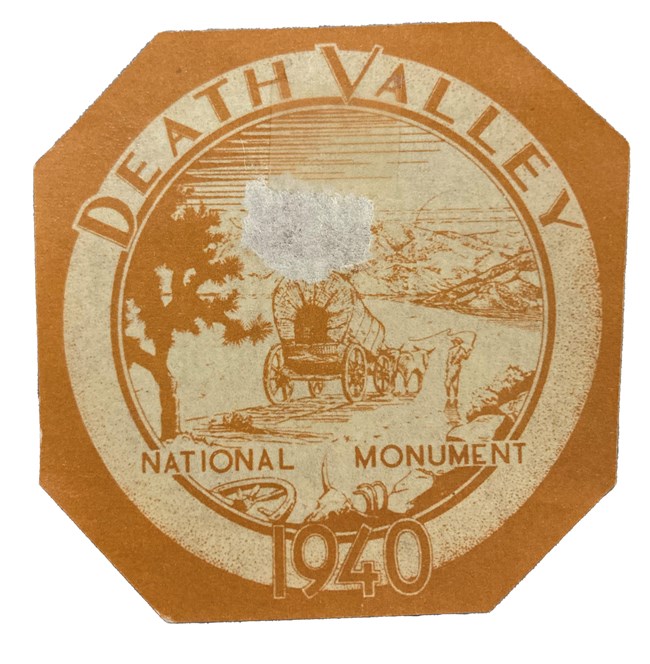

- Death Valley National Monument (prospector and burro), Pinnacles National Monument (flying bird), and a redesigned Lassen Volcanic (volcano) by 1936

- Redesigned Death Valley National Monument (covered wagon) in 1937

- Devils Tower National Monument (tower) by 1937 (uses a distinct font)

- Cedar Breaks National Monument (breaks scene) by 1938

- Platt National Park (bird) by 1937.

The stickers were reduced in size again (to 2.25 inches) and some featured landscapes, objects, and figures rather than animals. Although the octagonal shape remained, some of the new national monument stickers used different fonts. Some stickers featured different layout with the park or monument name surrounding the image rather than across the top as in earlier stickers.

(Mostly) Anonymous Art

The windshield stickers weren’t just evidence a fee was paid. Those created in the 1920s were the first NPS-produced graphic art to take hold of the public imagination. No information is available for most of the artists or about the decision-making process behind the end products. It’s possible that these little lithographs were printed by the Government Printing Office (GPO), but that can't be confirmed with available GPO catalogs. Arguably, another more likely possibility (at least for the stickers printed in the 1930s) is that they were printed by the Columbia Planograph Company in Washington, DC. The NPS used the company to print its first posters, created by Dorothy Waugh, from 1934 to 1936. In addition, the company printed a series of 50 envelope stickers, also designed by Waugh, in 1936.

Most of the designs are not signed. The artists are anonymous, except for two. The 1928 and 1936 Sequoia stickers and the 1936 Bryce Canyon stickers are signed J.J. Black. The Hot Springs sticker is signed J.J.B., also assumed to be Black. Little is known about Black or his career. In 1923 he was working as a cartographer for the US Department of the Interior. From at least 1934 to 1946 he also drew maps for NPS brochures.

Although the 1936 Hot Springs sticker is signed J.J.B., the first design was created in 1932 by Edward S. Zimmer. The September 1932 Park Service Bulletin notes, "The design for the sticker consists of a representation of an overflow from a hot spring and the rising vapors from the spring. It was drawn by Landscape Architect Zimmer, who was in the park at the time the matter was being studied." Zimmer worked on a variety of NPS projects, and played a pivotal role in design of the Natchez Trace Parkway. In the 1950s, he became chief of the NPS Eastern Office of Design and Construction.

The Third Time's a Charm

Although the recommendations from the 1923 and 1925 conferences to abolish the windshield stickers weren't acted upon, circumstances were finally right after the 1939 conference. More states and local governments had declared all but unofficial stickers unlawful. "Sticker hounds" were still plastering their cars with them. No longer content to only place them on windshields, some drivers added them to side and rear windows as well as the side wings. Organizations such as the American Automobile Association, the American Safety Council, and the American Planning and Civic Association supported banning windshield stickers other than those that indicate a car had passed state inspection.

The December 1939 Park Service Bulletin reported, “Upon recommendation of the park superintendents at the Santa Fe conference, the use of windshield stickers on automobiles has been discontinued and an effort is being made to find some suitable substitute for these stickers before the beginning of the next travel season.”

When Secretary of Interior Harold L. Ickes announced the decision to the press on December 29, 1939, the safety basis for the decision was stressed. “The popular windshield sticker issued as a receipt for automobile entrance fees will be abandoned by all national parks this year. The action was taken as a highway safety measure.” In spite of Ickes’ January declaration that there would be no windshield stickers after 1939, a 1940 sticker for Death Valley was made.

The article went on to state that the NPS was “attempting to find a practical and acceptable substitute—one that will meet the demand of the average motorist for visual evidence that he has ‘been places’ yet not obstruct his vision.”

An August 29, 1940, newspaper article reinforced the connection to highway safety, noting that the NPS was “cooperating with state and local governments in efforts to abate the increasing tendency of motorists to cover their windshields with stickers.”

Safety was certainly an important factor, but arguably state laws and visibility were seized upon to finally end a popular product that the NPS has been trying to stop for 15 years. Although Ickes promised an "acceptable substitute," committees since 1923 had failed to come up with one. It's unlikely that another effort would succeed. Certainly nothing was produced before the United States entered World War II in December 1941.

After the war ended, the first self-adhesive bumper stickers were created in 1946. Americans had a new way to decorate their cars and show off where they’ve been. Although the NPS began issuing new permits for travel trailers in the late 1940s, they were revenue stamps added to blue motor vehicle permits rather than windshield stickers.

A few parks eventually reintroduced windshield stickers as seasonal passes but they were usually rectangular, utilitarian, and had limited graphic appeal. Many parks still issue windshield stickers to employees to make it faster for them to get through entrance stations. In 1983 Glacier National Park used the original mountain goat design for a special sticker to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Going-to-the-Sun Road. Around 1988 Ed Rothfuss, superintendent at Death Valley, reintroduced the covered wagon windshield sticker as a seasonal entrance pass. It was in use until about 1995.

Rare Survivors

Determining exactly when a park or monument first used a windshield sticker has been difficult. NPS records primarily refer to "automobile permits" ranger than windshield stickers, decals, pasters, or stamps. As discussed above, windshield stickers are known to exist from parks before they officially charged an automobile license fee.

This verified list has been compiled from examples in NPS collections and with help from collectors who have graciously shared images of their collections. If you have examples, please email HFC_Archivist@nps.gov to share and we will update this list. Those marked with an asterisk after the year are believed to be correct but no surviving examples are known.

- Acadia (1935 earliest known example)

- Bryce Canyon (1929 fee charged; 1930 earliest known example)

- Cedar Breaks (1938 earliest known example)

- Colonial National Monument (1931, created for the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Yorktown)

- Crater Lake (1919*)

- Death Valley (1936 earliest known example)

- Devils Tower (1937 earliest known example)

- General Grant (1919*)

- Glacier (1919*)

- Grand Canyon (1922)

- Grand Teton (1929 fee charged; 1932 known example)

- Hot Springs (designed in 1932 but 1933 is the earliest known example)

- Lassen Volcanic (1925)

- Lassen Volcanic (1931 special park dedication sticker)

- Pinnacles (1923 diamond-shaped special sticker; 1936 earliest known octagonal example)

- Platt (1937 earliest known example)

- Mesa Verde (1919*)

- Mount Rainier (1919)

- Rocky Mountain (1922)

- Sequoia (1919*)

- Wind Cave (1923*; 1924 earliest known example)

- Yellowstone (1918)

- Yosemite (1917 and 1918 were round; 1919 is octagonal)

- Zion (1922 earliest known example)

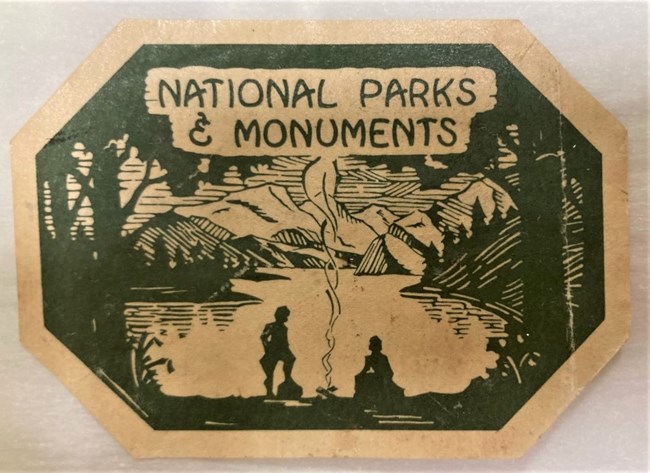

The NPS approved a general windshield sticker for national park and monuments in September 1937. It was illustrated in the October 1937 Park Service Bulletin which noted they were

for distribution when supplies of the individual national park stickers issued yearly begin to run low. Supplies of the sticker, when printed, will be forewarded to parks and monuments and the name of the particular area making distribution will be stamped on the back of each sticker as issued.

The example in the NPS History Collection is stamped for Petrified Forest National Monument. Surviving examples in private collections are known from:

- Boulder Dam National Recreational Area

- Colorado National Monument

- Craters of the Moon National Monument

- Grand Canyon National Park

- Grand Teton National Park

- Petrified Forest National Monument

- Yellowstone National Park

The Yellowstone sticker is stamped 1938. It seems likely that these were only issued through 1939 when the use of windshield stickers ended, but parks may have continued to use them until supplies ran out.

Sources:

-- (1915, March 25). “Valley City is on Coast-to-Coast Trail.” The Weekly Times-Record (Valley City, North Dakota), p. 6.

-- (1918, May 23). “Lost.” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), p. 4.

-- (1919, May 31). “Reflections on the Reliability Run.” Stockton Evening and Sunday Record (Stockton, California), p. 28.

-- (1919, June 8). "Map Air Routes to Yosemite." The Fresno Morning Republican (Fresno, California), p. 17.

-- (1920, August 7). “Stockton to be Located on Wonder Highway Connecting National Parks. Stockton Evening and Sunday Record (Stockton, California), p. 1-2.

--(1921, September 11). “Gathering Park Permits Latest Fad of Motorists.” Modesto Morning Herald (Modesto, California), p. 15.

-- (1922, February 17). “Wants Capital Motorists to Visit National Parks.” Evening Star (Washington, District of Columbia), p. 6.

-- (1922, May 5). “License Labels on Girls’ Backs.” The Long Beach Telegram and The LongBeach Daily News (Long Beach, California), p. 3.

-- (1923, April 7). “Park Windshield Stickers to Show Native Animals.” Stockton Evening and Sunday Record (Stockton, California), p. 37.

-- (1923, November 2). “’Stickeritis’ Motordom’s Latest Disease.” Monrovia Daily News (Monrovia, California), p. 6.

-- (1923, November 3). “Wanted: An Idea to Supplant Park Windshield Sticker.” Stockton Evening and Sunday Record (Stockton, California), p. 25.

-- (1924, June 21). “Smaller Windshield Sticker Now Issued in Yosemite Valley.” The Fresno Bee (Fresno, California), p. 21.

-- (1924, July 22). “Windshield Stickers to Advertise S.F.” The San Francisco Examiner (San Francisco, California), p. 4.

-- (1937, October). "Issuance of General Automobile Sticker Approved." Park Service Bulletin, Vol. VII, No. 9, p. 7. Assembled Historic Records of the NPS (HFCA 1645), NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry, WV.

-- (1939, September 15). "Warning issued to 'Sticker Hounds'". The Arroyo Grande Valley Herald Recorder (Arroyo Grande, California), p. 2.

-- (1939, December 29). “National Parks Auto Stickers Discontinued.” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), p. A7.

-- (1940, January 2). “Ickes Prohibits Windshield Tag.” The Odgen Standard-Examiner (Odgen, Utah), p. 11.

-- (1940, August 29). “National Parks Service Bans Windshield Stickers.” Iron County Record (Cedar City, Utah), p. 4.

-- (2001, Spring). “Remember Zoo Windshields, Anyone?” Arrowhead The Newsletter of the Employee & Alumni Association of the National Park Service, Vol. 8, No. 8. Eastern National, p. 4.

Department of the Interior. (1917). Report of the Director of the National Park Service to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1917. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC.

Department of the Interior. (1919). Report of the Director of the National Park Service to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1919. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC.

Department of the Interior. (1920). Report of the Director of the National Park Service to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1920, and the Travel Season 1920. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC.

Department of the Interior. (1921). Report of the Director of the National Park Service to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1921, and the Travel Season 1921. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC.

Department of the Interior. (1922). Report of the Director of the National Park Service to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1922, and the Travel Season 1922. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC.

Department of the Interior. (1923). Report of the Director of the National Park Service to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1923, and the Travel Season 1923. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC.

Gale, E.W., Jr. (1923). “Motordom’s Latest Disease.” Automobile Club of Southern California, Vol. 15, p. 17.

Krahe, Diane L. and Catton, Theodore. (2010, September). Little Gem of the Cascades: An Administrative History of Lassen Volcanic National Park. Accessed March 16, 2023 at Little Gem of the Cascades:An Administrative History of Lassen Volcanic National Park (npshistory.com)

MacIntosh, Barry. (1983). “Visitor Fees in the National Park System: An Administrative History.” Accessed March 11, 2023, at https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/mackintosh3/index.htm

MacIntosh, Barry. (1995). “Former National Park System Units: An Analysis.” Accessed March 11, 2023, at https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/hisnps/NPSHistory/formerparks.htm

Martin, Peter. (2006, March-April). “Canada National Park License is Rare.” The American Revenuer, Vol. 60, No. 2, pp. 52-53.

Morse, Rusty. (2011, January-February). “Those Wonderful National Park Revenues, 1917-1940.” Scribblings from the Rocky Mountain Philatelic Society, Vol. 19, No. 1, pp. 1-3.

National Park Service. (1939, December). “Administration.” Park Service Bulletin, Vol IX, No. 9, p. 7.

Pers. comm. (2023, March 16). Email and images from Benjamin Farr to Nancy Russell, NPS History Collection archivist.

Pers. comm. (2023, March 14). Email and images from Paul Stolen to Nancy Russell, NPS History Collection archivist.

Pers. comm. (2023, January 22). Email from Ed Rothfuss to Nancy Russell, NPS History Collection archivist.

Sheldon, Andrew. (2021, May 11). “The Unique History of Bumper Stickers.” Accessed 12/28/2022 at https://magazine.northeast.aaa.com/daily/life/cars-trucks/auto-history/bumper-stickers/

Tags

- acadia national park

- bryce canyon national park

- cedar breaks national monument

- colonial national historical park

- crater lake national park

- death valley national park

- glacier national park

- grand canyon national park

- hot springs national park

- lassen volcanic national park

- mesa verde national park

- mount rainier national park

- petrified forest national park

- pinnacles national park

- rocky mountain national park

- sequoia & kings canyon national parks

- yellowstone national park

- yorktown battlefield part of colonial national historical park

- yosemite national park

- zion national park

- nps history collection

- nps history

- art

- hfc

- tourism

- automobile

- windshield sticker

- fee