Last updated: March 27, 2023

Article

50 Nifty Finds #17: Common Threads

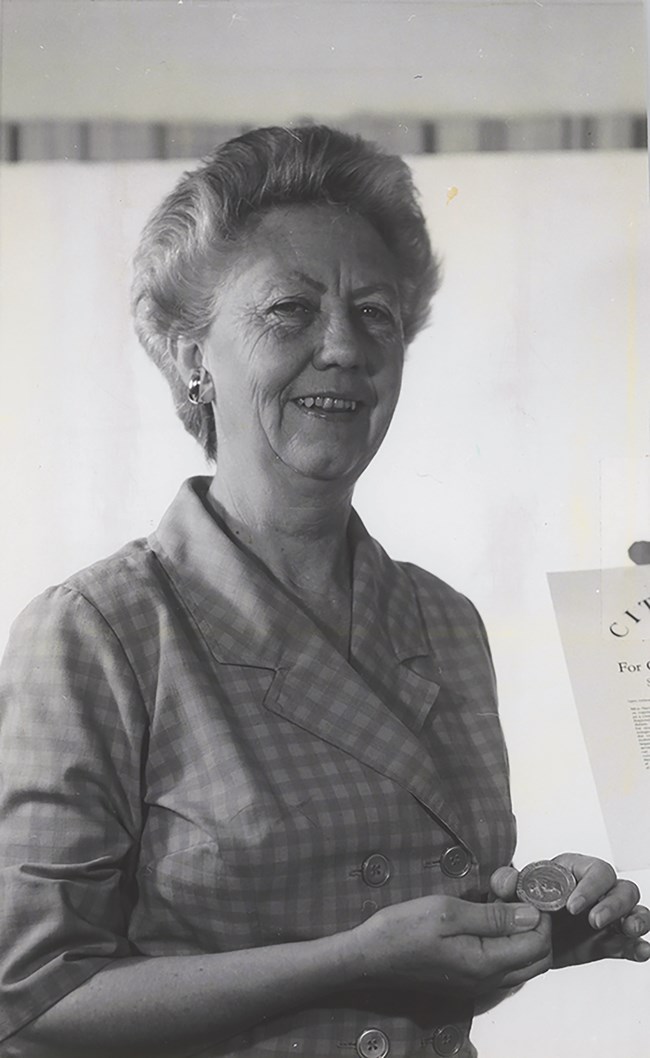

Each National Park Service (NPS) employee has a unique story. We can't tell them all, but sometimes there's a personal account—like that of Sallie Pierce Brewer Van Valkenburg Harris—that speaks to common experiences. Told through oral histories, photographs, documents, and objects in the NPS History Collection, Sallie's story resonates regardless of time, gender, or position. Her career highlights a mix of issues and emotions: the important roles NPS spouses play and their struggle to have their own careers; the toll remote NPS assignments can have on relationships; gender discrimination; the importance of humor; frustration with hiring rules; struggles to compete for temporary and permanent jobs; the desire to feel useful; getting let go even when you are doing great work; discomfort of ill-fitting uniforms; dissatisfaction with the pace of career advancement; love for the job; commitment to the NPS; and more. Although her career spanned from 1933 to 1971, many of her joys, challenges, and frustrations can still be recognized in the NPS today.

The Early Years

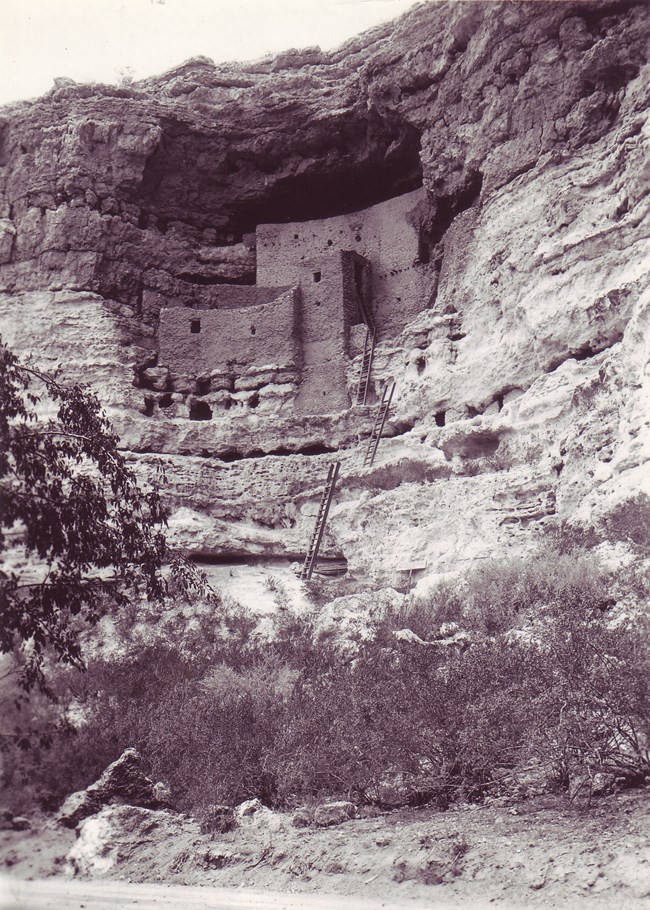

Sarah Louise Pierce, known as Sallie, was born April 13, 1911, in Victor, Colorado. Her parents were Colwell Pierce and Mary Rood. Colwell was in the mining industry. She had two younger brothers, one of whom died in infancy. The family moved to Patagonia, Arizona, before she was two years old. She graduated high school there but then moved to Carlsbad, New Mexico, with her family before starting college. When she was about 10 years old, her family took a trip to Grand Canyon National Park, visiting national monuments along the way. She recalled that Frank “Boss” Pinkley, custodian of Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, gave them a tour of the site and recommended they go to Montezuma Castle National Monument. The custodian there, Martin Jackson (father of Earl Jackson), toured them through the site by flashlight. The Pinkley and Jackson families would become Sallie's friends and colleagues.

In 1928 Sallie enrolled at the University of Arizona in Tucson, earning a BA in archaeology in May 1932. Because the University of Arizona wouldn’t take women on prolonged field trips at that time, she did summer field schools in archeology with the University of New Mexico. She worked at Jemez in 1931 and, after graduation, at Chaco Canyon in 1932. One of her classmates was Nancy Pinkley, daughter of Frank and Edna Pinkley. Sallie visited the family at Casa Grande.

In January 1934 the Civil Works Administration (CWA) hired Sallie to clean, catalog, and study artifacts excavated at the Castle A site at Montezuma Castle. The CWA was a short-term Federal Emergency Relief Administration program to help jobless Americans get through the hard 1933-1934 winter. It only ran from November 1933 to July 1934. Although most CWA jobs ended on March 31, 1934, Sallie’s job lasted through April that year.

By the early 1930s Colwell Pierce was working in the same mining company as former NPS Director Horace M. Albright. That relationship appears to have influenced Albright to write to Robert H. Rose, assistant superintendent at Casa Grande, on Sallie's behalf in 1934. Rose replied on February 16, 1934, that “if firsthand observation proves as convincing as her good qualification record, she should be excellent material for the National Park Service.” He was quick to point out, however, that “because of the rigorous living conditions in various monuments I believe for our new position of junior park naturalist of Southwestern Monuments only a man should be considered for the appointment.” He noted plans to hire a museum preparator in the future, work that would be largely done at park headquarters and, therefore, “it would make little difference whether this position were filled by a man or a woman.”

On February 20, 1934, Albright responded to Rose:

I agree with you that being a girl she could not fill the post of junior park naturalist, because of the vast amount of traveling that must be done and the lack of suitable quarters to accommodate her in the various monuments. However, she is a very capable girl, and I wish she could be situated at one the monuments or parks. She would give a splendid account of herself if such a place could be found for her.

Women weren’t consulted before NPS men determined what was suitable for them. The irony is that as wives of park rangers, many women lived (and often worked) in the same difficult conditions—they just didn’t get paid for it.

The HCWP Years

Sallie’s CWA appointment ended, and she married ranger Jim Brewer on July 19, 1934. In 1936 she passed the civil service examination for junior park archeologist. She recalled, “I was on one or two civil service lists by then, and I did get one or two offers of positions, but—now this is where I'm very old fashioned and conservative—I always felt if you were married, you stayed with your husband [back then].”

In 1923 “Boss” Pinkley became the general superintendent of the Southwestern National Monuments. Having had the support of his wife Edna at Case Grande until her death in 1929, he understood what great assets park wives were. He did more than just acknowledge the wives with the affectionate (but unofficial) titles of “honorary custodians without pay" (HCWP) or “honorary ranger without pay” (HRWP). He asked for their opinions on housing issues, insisted that they were part of their husbands’ transfer decisions, and gave them credit where it was due in his monthly reports to the NPS Washington office. Sallie recalled:

He was a very supportive person. He did get a rather unusual bunch of people [working in the national monuments]. [He once wrote] he wasn't sure whether the kind of men that liked his outfit just naturally chose the kind of women who liked it, or whether they've been extraordinarily lucky. He always played up the fact that we were equal partners. We didn't get paid, but he listened to us. He paid attention to our comments, made us feel as if we were doing part of the work and were worthy of being considered—which of course raised the morale of both wife and husband, tremendously. He was sincere about it, too. He had a great respect for women.

Pinkly understood that many of the wives were well educated and just as qualified as their husbands. When Jim Brewer got a temporary position as a ranger at Wupatki National Monument the day before their wedding, Pinkley wrote “We think we’re doing well when we can angle for one archaeologist and get two!”

Sallie was an HRWP or HCWP for almost eight years. They lived in eight monuments, staying in tents, a log cabin, Navajo hogan, and thousand-year-old pueblo. It was six years before they lived in an NPS house. For a while they used the ranger pickup truck for storage and food preparation while they slept on the ground next to it. In the summer of 1937 Brewer was a “roving ranger,” and they traveled to many monuments. Sallie’s experiences (and those of so many other park wives) challenge the sincerity of NPS arguments that women couldn’t be rangers or ranger-naturalists due to lack of “suitable housing.” In addition to keeping house in these challenging circumstances, Sallie greeted visitors, helped make park signs, typed reports, and led tours in her husband’s absence.

At Wupatki the Brewers became friends with their Navajo neighbors. Sallie was particularly interested in helping the families market their crafts. Together with the Museum of Northern Arizona, they sponsored a Navajo craft exhibit in June 1936. Sallie interviewed Peshlakai Etsedi about his boyhood memories of the Long Walk, the forced exile of Navajos to Bosque Redondo from 1894 to 1868. She also co-founded The Grapevine newsletter to share information and make connections among the wives.

The Ranger Years

As men rangers went off to fight in World War II and following her husband Jim’s enlistment in the US Navy Seabees, Sallie started looking for a job. She sent an application to Charles A. Richey, superintendent of the Southwestern National Monuments, on October 19, 1942, noting, “The enclosed application form means that I would prefer Park Service work to anything else I might be able to do while Jim is away. . . Sometime near the end of this year or the first of next I’ll probably be looking for a job.”

In a November 20, 1942, letter to Richey she wrote:

My application seems to have given you the impression that I am interested chiefly in a ranger position—and that isn’t entirely the case. [It] was meant to point toward a possible vacancy in the naturalist office in Santa Fe. I realize that the naturalist division might be kept at skeleton strength for the duration but supposed they might need office helpers. Since writing my application I have taken the typist-clerical test…Ranger work would interest me (at some monuments, very much)—but I’m afraid that what the Service might consider ‘suitable’ locations for a woman ranger would be boring in contrast to my experiences as an HCWP. Rather than do the “merry-go-round” at Aztec or Casa Grande I’d take less salary in Santa Fe. I naturally want to feel that [the work] I do while Jim is away needs to be done, work in which I’ll be interested, and work that will train me to support myself better afterwards, if that should be necessary.

Richey responded that the position in the naturalist office could not be filled, but “I have been considering you for a ranger position at Casa Grande National Monument.” He went on, “I believed that you had been permanently employed with this Service during the CWA program. After checking the matter, however, I find that your work was not on a full-time basis. This has considerable bearing on placing you in a position at this time.” Discussing the options he noted,

Because of your training in anthropology and archeology, I would prefer to try and place you in a ranger position. Because of the general isolation of most of our areas, there are only two or three which I might want to place any of our HCWP. These are Casa Grande, Montezuma Castle, and Tumacacori. We may not be able to fill some of the above-mentioned positions if they become vacant because of war conditions. However, I feel certain that they will let us fill the position at Casa Grande which is now vacant. I feel that you could be of great value to the Service in the position at Casa Grande and I shall make every effort to place you there if this is agreeable to you.

Sometime in late 1942 Sallie wrote Hugh Miller, NPS Personnel Officer and a friend from her days as an HCWP when he was superintendent of the Southwestern National Monuments. Following pleasantries, he responded:

The Service is anxious to do so wherever practicable and from my point of view nothing would be more logical than to employ the wives of employees who enter the armed forces. Your case went right up to the department with our fervent blessing, and we hope to hear from it very soon. Should there be objection on the part of the Civil Service Commission, we will suggest the re-designation of the position to junior archeologist, and then there can be no objection as I believe I recall that you are eligible on that register. But in any case, the replacement of men of military age by women wherever practicable is clearly in the trend and an absolute necessity for the nation as a whole if its man-power requirements for 1943 are to be met.

Sallie got a war service indefinite appointment at Casa Grande on February 16, 1943. Her salary was $240 per year. Her appointment letter reads:

The Headquarters Office takes pleasure in advising you of your appointment to the position of ranger at Casa Grande National Monument. May the entire headquarters staff offer congratulations and officially welcome you to the organization. Although you have been an esteemed HCWP, you now have the distinction of becoming the first woman ranger on regular assignment, not only in Southwestern National Monuments, but also in Region Three.

Other authors have credited Sallie with being the first woman ranger hired in the Southwestern National Monuments but as noted above she was the first “on regular assignment.” Although most of the uniformed women in the 1930s and 1940s were hired as guides or museum aids rather than rangers, there were a couple of women rangers before Sallie in Region Three, which included Arizona, Arkansas, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Texas, Nevada, Utah, and parts of Southern Colorado. Gay Rogers was a seasonal park ranger at Aztec Ruins National Monument in summer 1934. Polly Mead was a ranger-naturalist at Grand Canyon National Park from 1929 to 1931.

Sallie was hired to replace ranger Peter H. Schuft who joined the US Navy. Around May 1944 she was offered a curatorship of the Heard Museum in Phoenix. She turned it down noting, “I have a war service appointment with the Park Service. I’ve lived on national monuments with my husband for the past ten years and have been a ranger here for a year and a half. In other words, I am pretty thoroughly broken into Park Service work and (considering their difficulty in obtaining men now) feel that I am doing more good here than I would be if I were to change positions.”

As a ranger Sallie needed a uniform. The first problem she encountered was determining what the NPS uniform for women was. In the 1930s women wore the standard NPS uniform shirt, tie, and coat with a skirt instead of trousers. Efforts by the women’s uniform committee to create the first separate uniform for NPS women stalled when the United States entered the war. On March 4, 1943, Superintendent Richey wrote to John C. Preston, chairman of the NPS uniform committee noting,

We now have one permanent woman ranger in our organization, and there is a good chance that we will employ other women in ranger or custodial positions. As we do not intend to employ more than one woman ranger in an area, the matter of uniformity does not concern us a great deal. However, we would like to conform to the Service’s regulation for women’s uniforms, if one has been definitely established.

He went on to express concerns about the NPS uniform at Casa Grande where temperatures exceeded 100°F in the summers. Preston responded, “In the absence of a standard uniform, make your own decision in regards to the type of women’s uniform most suitable for the areas under your supervision.” After some back and forth with Richey, by April Sallie had put together her experimental uniform. It consisted of a green six-gore skirt, beige Pima cotton shirt with open sport collar and short sleeves, beige socks, brown loafer-type shoes, and the NPS tan sun helmet. Letters reveal that photographs of her wearing the uniform were taken, but their location is unknown.

On May 15, 1943, Preston proposed a uniform for two rangers he had hired at Mount Rainier National Park. It consisted of a Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WACC)-style coat, skirt, long-sleeved gray shirt, green tie, overseas cap, brown oxford shoes, and a belt made from the official NPS hatband. Later that month his proposed uniform was approved for 1943 “on an experimental basis,” adding neutral stockings and making the belt optional. Sallie continued to wear her uniform throughout the summer at Casa Grande. She recommended that uniform as the “hot climate uniform” in a memo to the Region Three director on September 6, 1943, changing the shirt from tan to gray.

On October 11, 1943, Sallie wrote to the Fechheimer Brothers Company to place her order for the uniform described by Preston—only to be told that they didn’t have shirts with collar size less than 14 inches or sleeves shorter than 32 inches. They recommended that she buy shirting fabric and use a local dressmaker to make up the shirts. The lack of shirts sized for women would be a problem for women for decades to come. Women often purchased fabric for shirts or skirts to try to solve problem themselves. Sallie’s papers in the NPS History Collection detail her struggle throughout the 1940s to get uniform items that fit—something that many NPS women can still relate to today.

Even with her modified uniform, the extreme heat at Casa Grande was difficult for her, and she requested a transfer. On June 6, 1944, she became a ranger at Tumacacori National Monument (now a national historical park). She encouraged a woman she knew to take her place at Casa Grande. Jessica Shearwood became the second woman park ranger there in July 1944. She remained in that position until May 31, 1945.

Custodian Earl Jackson was her supervisor. She and Jackson were the only two employees at the monument. She later recalled,

So being two people there, you did a little bit of everything. I took care of the garden. I took more than half the trips [public tours] because he had the administrative paperwork to do. You had trips at established times. It's always been my feeling that you protect to the extent that you inform the public and are a gracious host or hostess to the public. So, the trips as we conducted then really combined interpretation and I think a lot of what would now be called protection. We were doing a little bit of everything. Occasionally you did have to get a little tough with somebody, but a soft answer was better usually than being badge heavy, as we used to call it. It was nothing that a woman couldn’t do.

While there, she received two pay increases, until she was earning $3,725 per year.

The Brewers divorced when Jim returned from military service in 1945. Sallie was very aware that her war service appointment would expire when “the duration” was declared over. Miller wrote to her on December 7, 1945:

I have read your memorandum of December 16 for the regional director concerning your status and assume you wish my comment. I am making it unofficially. You do not have competitive status and the war service appointment which you hold is limited to the end of the duration and six months. My thought for you was that you might escape displacement during the reconversion period and, finding yourself still on the rolls when the duration is declared to an end, then request competitive status on the basis of your eligibility on the old junior archeologist register. I had hoped that this end might be reached by changing the designation of your position at Tumacacori from park ranger to historian, at approximately the same salary as there is little likelihood that there will be any women rangers when things get completely back to normal, but such a change is an administrative matter which I am not at liberty to initiate officially so that if you work on it, you should work on it from that end without bringing me into it.

He went on to note that the Civil Service Commission didn’t plan to restart permanent competitive appointments until “the veterans are all back and free to compete for them. . . You should not regard this letter as necessarily too discouraging as the employment situation ought to be all straightened out in about six months and you may never be reached in the reduction in force that will be necessary in some areas to accommodate returning veterans.”

Sallie had the support of NPS management but ultimately couldn’t compete with returning veterans. On March 28, 1950, Jackson wrote to her, “The Washington Office has informed me that as a result of a thorough analysis of the park ranger register and of the use that was made of it, they have come to the conclusion that early displacement of those incumbents who failed or did not compete in the examination is necessary. You are, accordingly, advised that your separation from your present position of park ranger will be effective on May 31, 1950, at the close of business.”

Jackson went on to note, “The regional office has advised me that every effort will be made to find a suitable place for you after your employment is terminated.” When Jackson’s memo reached the NPS personnel office, Miller wrote to her that he “almost wept” on reading it. He explained all that had been done to try to keep her after her displacement from her ranger position and why it wasn’t possible to hire her as either an archeologist or a historian. He wrote,

At any rate we hope you will realize that we still all love you, that this action was forced upon us, and that we have honestly exhausted every channel that offered any promise of solving the problem. [We] often speak of you and about the old days in the Southwestern Monuments. The admiration and affection with which we regarded you then has not been diminished by the years between and it won’t, somehow, be quite the same National Park Service if by chance you should no longer be in it.

He closed his letter with the observation, “Of course, we’ve been expecting that some rich rancher might at any time convince you that you are one flower which should not ‘waste its sweetness on the desert air’ and maybe you would have been leaving us before long anyhow.”

Digging Herself a Career

From 1943 to 1950 Sallie served as acting custodian at Casa Grande and Tumacacori, covering during absences and gaining experience in small-area operations. In 1949 she received this complement from NPS Assistant Director Hillory A. Tolson: “I was very favorably impressed by the way in which Ranger Sallie Brewer handed the visitors which Tillotson and I joined when she took us through the museum and the old mission. Sallie is doing such a grand job.”

Her great work and friends in high places weren't enough to keep her job given the civil service regulations. Sallie’s war service appointment officially ended on June 7, 1950. Ten days later she started a temporary ranger appointment at Bandelier National Monument in Santa Fe, New Mexico. The job included conducting tours, working in the entrance stations, and serving as fire dispatcher in case of forest fire. The job only lasted four months, during which the NPS director received a letter from two members of the public praising Sallie. They wrote, “her manner was most pleasant and friendly, and she did not give the impression of merely reciting the same spiel for the nth time.”

At loose ends after her job at Bandelier ended, Sallie took a trip to Mexico. Luis Gastellum, a clerk in Region Three, tracked her down there with a job offer at the regional office. Brewer described him as “a great guy who knew all the rules and so made it possible to do things that had to be done.” She received a probational archeologist appointment, subject to furlough, on January 2, 1951. In March that year the position was converted to full-time. Her duties included preparing correspondence on subjects such as interpretation and general policy, answering archeology and history questions, managing the Region Three library, and assisting in research and planning for history and archeology projects. She conducted test excavations at Tumacacori in 1951 for a road-widening project. She also published two articles from her analysis of artifacts recovered from Gran Quivira Ruins (part of Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument).

She was promoted in October 1952, but her position was made subject to furlough again in July 1954. Her job was eliminated through a reduction in force action on August 3, 1954. Brewer recalled, “There was a huge re-organization that included moving many people to the west coast. Out of 80 positions two had to be abolished; another woman and I were fired.” She also noted that both of them were married. Sallie had recently married archeologist Richard Fowler Van Valkenburg. She recalled, “The regional director said I had remarried so I didn’t have to work. As a matter of fact, I was broke.” She was Van Valkenburg’s third wife. They didn’t live together for much of their marriage but wrote to each other often, usually about his research. They divorced in the 1954 when Van Valkenburg returned to his second wife.

Within days of her losing her job in the regional office, she got a temporary job as a ranger-naturalist at Grand Canyon National Park at a much lower salary. The position only lasted three months. She was offered an archeologist job at Tonto National Monument but turned it down. She preferred seasonal jobs that let her continue her research at Casa Grande and Walnut Canyon national monuments. Between December 1954 and July 1956, she worked winters at Casa Grande and summers at Walnut Canyon. These seasonal archeologist positions paid less than she earned as an archeologist in 1951. In addition to her regular duties, she wrote the area history for Casa Grande and (on her own time in 1955 with equipment borrowed from the University of Arizona) began an archeological survey of the north rim of Walnut Canyon. She later completed that survey and published an article on it in 1961. She noted, “This assignment combined the activities I most enjoy: being in the field, locating new information, and making it a matter of record.”

In August 1956 she got a job as a GS-5 archeologist at Montezuma Castle. She recalled that John Day, general superintendent of the Southwestern National Monuments, encouraged her to take position. A few months later the Southwestern National Monuments administrative office was disbanded. Sallie believed that he encouraged her to take the permanent position because he knew what was coming. “I probably would have found it difficult to continue, not being a young person by then, doing the seasonal work back and forth all the time.”

She was promoted to a GS-7 archeologist on February 14, 1958. The job included more interpretive planning than archeology as she “bridged the gap” of inadequate staffing at the monument. Sallie revised the self-guided booklet, updated the exhibits, planned trailside exhibits, and many other projects. She also wrote the monument’s Mission 66 Prospectus brief, the general information and interpretation sections of the master plan, and the museum prospectus for the visitor center. She was given an incentive award for the interpretive improvements she made at the site.

Sallie was promoted to a GS-9 museum curator with the Region Three office on November 16, 1958. She was duty stationed at the Southwestern Archeology Center in Globe, Arizona. Her job was reclassified as a museum specialist in 1963. On September 21, 1966, she was reassigned to the Division of Archeology Studies in the NPS Washington Office but remained duty stationed in Globe.

She married William M. Harris Jr., a railroad engineer, on August 25, 1965. They divorced sometime in the 1970s. She once joked, “I must be a record divorcee in NPS.” She retired on October 23, 1967, due to a degenerative disk disease which impaired her ability to work. Throughout her 24-year career, Sallie never rose above a GS-9 position despite her education and experience. She recalled, “I wasn’t an aggressive or competitive person but I was competent.” At the time Jean Pinkley was the only woman archeologist in the Southwest who had risen to a supervisory position. “I didn’t think that was quite fair, but you didn’t make a point of it in those days.” Throughout her career she sometimes got letters from women who hoped to join the NPS but was always unsure how to answer them. “A letter discouraging them would have been more truthful but not complimentary to the NPS."

Sallie wrote or co-wrote research articles about archeological sites. Depending upon when they were written, her name was recorded as Sarah Louise Pierce, Sallie Brewer Pierce, Sallie Brewer Van Valkenburg, Sallie Pierce Van Valkenburg, Sallie Pierce Harris, and Sallie Van Valkenburg Harris. She once remarked, “I used to say laughingly that I publish every five years.”

Like many NPS employees, Sallie retired but continued to work for the NPS. She received an appointment as an unpaid collaborator at Canyon de Chelly National Monument within a month of retiring. She led a project to conduct oral history interviews with Navajo elders. In 1968 she received the Commendable Service Award in honor of her contributions to the field of archeology. Although the oral history project only lasted about a year, her collaborator status officially ended on November 17, 1971.

In retirement Sallie was active in environmental organizations like the National Audubon Society. She moved to Prescott, Arizona, in 1981. Sallie Pierce Brewer Van Valkenburg Harris died May 2, 1994, age 83.

Sources:

--. (1944, July 15). “Assignment Changes Made in US Parks.” Tucson Daily Citizen (Tuscon, Arizona), p. 5.

--. (1994, May 6). “Harris, Sallie Pierce.” Arizona Daily Star (Tucson, Arizona), p. 18.

--. (2016, November 19). “Civil Works Administration (CWA) (1933).” Accessed March 3, 2023, at https://livingnewdeal.org/glossary/civil-works-administration-cwa-1933/

Clemensen, A. Berle. (1992, March). Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, Arizona: A Centennial History of the First Prehistoric Reserve 1892-1992. Accessed March 5, 2023, at https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/cagr/adhi6a.htm

Kaufman, Polly Welts. (2006). National Parks and the Woman’s Voice: A History. University of New Mexico Press: Albuquerque.

NPS History Collection (2019).“Dressing the Part: A Portfolio of Women’s History in the NPS.” Accessed March 5, 2023, at https://www.nps.gov/subjects/hfc/dressing-the-part.htm

Sallie Brewer’s personal files in the Polly Kaufman Collection (HFCA 1980), NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry, WV.

Sallie Pierce Brewer Van Valkenburg Harris interview transcript (1978, October 11). Interview with Dorothy Huyck, NPS Oral History Collection (HFCA 1817), NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry, WV.

Sallie Pierce-Harris Collection, 1918-1994 finding aid, Museum of Northern Arizona. Accessed March 3, 2023, at http://azarchivesonline.org/xtf/view?docId=ead/mna/MNA_MS309_PierceHarris.xml&doc.view=print;chunk.id=0

Tags

- aztec ruins national monument

- bandelier national monument

- canyon de chelly national monument

- casa grande ruins national monument

- grand canyon national park

- montezuma castle national monument

- navajo national monument

- salinas pueblo missions national monument

- tumacácori national historical park

- walnut canyon national monument

- wupatki national monument

- nps history collection

- nps history

- women

- women's history

- uniform

- hfc

- wives

- family

- ranger