Last updated: December 20, 2023

Article

2022 Weather in Review: Gauley River National Recreation Area

In order to better understand ecosystem health in national parks, the Eastern Rivers and Mountains Network measures ecosystem "vital signs" in select national parks in West Virginia, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York. One of those vital signs is weather and climate. Below is a summary of 2022 weather conditions at Gauley River National Recreation Area.

This brief provides county-scale weather data averaged from all of the counties surrounding the park, including data from 1895–2022 (i.e., period of record). These counties include Fayette and Nicholas counties, West Virginia. Data and analyses herein are courtesy of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA) Climate at a Glance Program.

Weather vs. Climate

First of all, what is the difference between weather and climate? Weather consists of the short-term (minutes to months) changes in the atmosphere. Weather is what is happening outside at this very moment, be it rain, snow, or just a warm sunny day. Climate is what you expect to see based on long-term patterns of over 30 years or more. An easy way to remember the difference is that climate is what you might expect, like a hot summer, and weather is what you get, like a warm rainy day.

The following information includes a discussion of 2022 weather placed in the context of long-term climate (i.e., how did 2022 compare to a "normal" year?).

2022 Summary

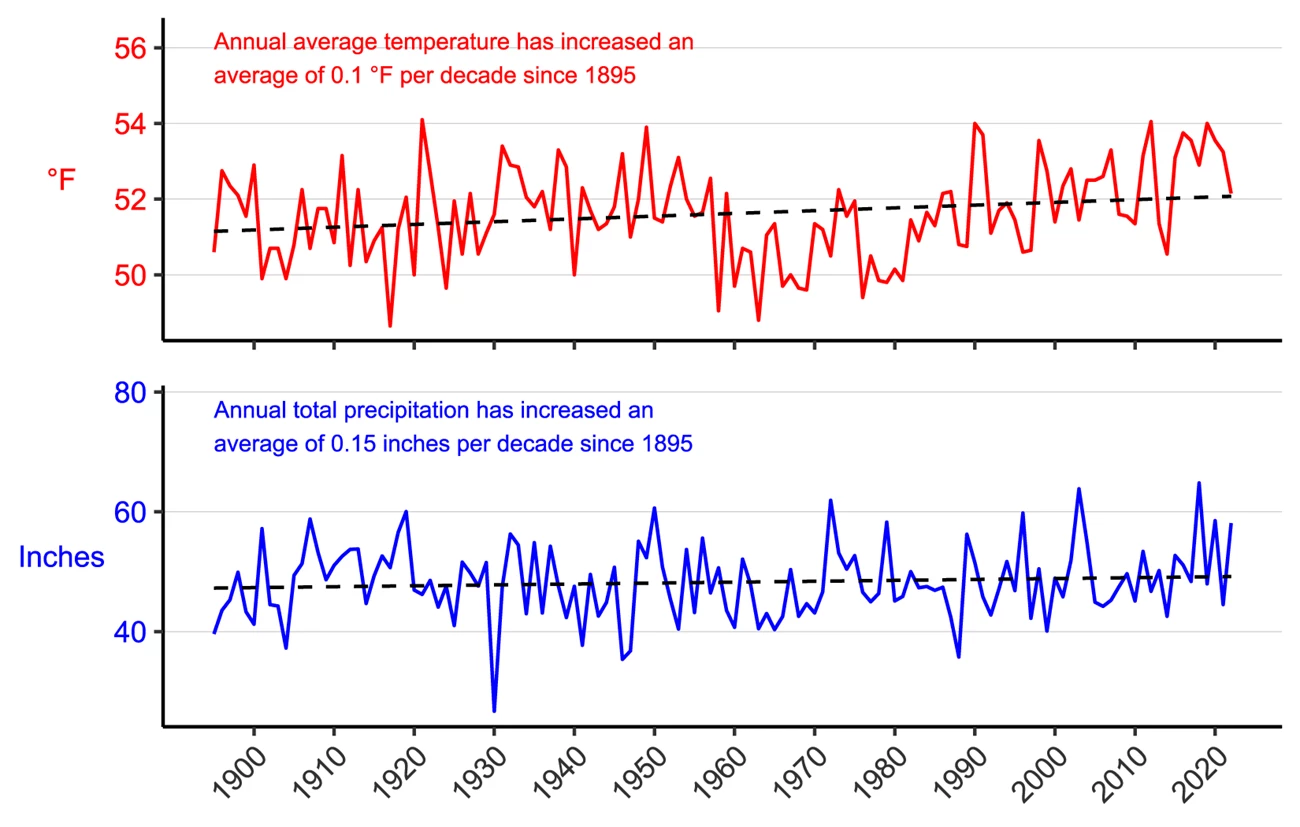

In all, 2022 was slightly warmer and much wetter than normal for Fayette and Nicholas counties, West Virginia. The year ended as the 41st warmest and 11th wettest on record. Data indicate that over the long term, annual average temperature and annual total precipitation have both increased (+0.1 °F per decade and +0.15 inches per decade, respectively).

Temperature

In total, 2022 was the 41st warmest year recorded in the counties surrounding the park (Figure 1). Seven months had higher than normal temperatures with Feburary, March, May, and November all being more than 2 °F above the long-term average (Table 1). That said, January and October were both abnomally cold (i.e., 3.5 °F and 3.4 °F below normal, respectively).

Table 1. Monthly and annual average temperature and departure from long-term averages. Departures from average show how different 2022 was compared to relevant averages from 1895-2021.

| Month/Year | Average temperature (°F) | Departure from long-term average (°F) |

|---|---|---|

| January | 27.3 | −3.5 |

| February | 35.5 | +2.4 |

| March | 45.2 | +3.7 |

| April | 51.0 | −0.3 |

| May | 62.7 | +2.5 |

| June | 67.2 | −0.2 |

| July | 71.8 | +0.8 |

| August | 70.5 | +0.6 |

| September | 63.5 | −0.8 |

| October | 50.1 | −3.4 |

| November | 45.2 | +2.8 |

| December | 35.3 | +1.6 |

| 2022 | 52.1 | +0.6 |

Precipitation

The year 2022 was extremely wet and ranks as the 11th wettest year recorded in Fayette and Nicholas counties, WV since 1895 (Figure 2). The summer was particularly wet, and spring and winter were also wetter than normal. In total, 58.11 inches of precipitation fell, almost 10 inches more than the long-term average (Table 2).

Table 2. Monthly and annual total precipitation and departure from long-term averages. Departures from average show how different 2022 was compared to relevant averages from 1895-2021.

| Month/Year | Total precipitation (in.) | Departure from long-term average (in.) |

|---|---|---|

| January | 5.50 | +1.74 |

| February | 4.27 | +0.94 |

| March | 2.54 | −1.73 |

| April | 3.37 | −0.59 |

| May | 5.93 | +1.40 |

| June | 6.92 | +2.10 |

| July | 8.34 | +2.84 |

| August | 7.32 | +2.80 |

| September | 4.14 | +0.71 |

| October | 4.10 | +0.90 |

| November | 3.29 | +0.02 |

| December | 2.40 | −1.16 |

| 2022 | 58.11 | +9.96 |

Temperature and Precipitation Trends

(1895-2022)

Data for Fayette and Nicholas counties, West Virginia indicate that annual average temperature has increased approximately +0.1 °F per decade and annual total precipitation has increased approximately +0.15 inches per decade since 1895 (Figure 3).

National Park Service scientists have forecast future changes in climate too. Models estimate that by 2100, annual average temperature at the park will increase by 2.9–8.8 °F (from a best-case to worst-case scenario, respectively). Annual total precipitation is expected to increase by 6–11% (see Gonzalez et al., 2018 for details).

Climate Change

Today's rapid climate change challenges national parks in ways we've never seen before. Wildlife migrations are altered, increasingly destructive storms threaten cultural resources and park facilities, habitat is disrupted—the list goes on. Go to the NPS Climate Change site to discover how climate change is affecting our nation's treasures, what the National Park Service is doing about it, and how you can help.For more information, contact Mid-Atlantic Network Biologist, Jeb Wofford or Eastern Rivers and Mountains Network Program Manager, Matt Marshall. Data included in this article were obtained from NOAA's NClimDiv dataset (version v1.0.0-20230106).