Last updated: May 6, 2024

Article

“Working in Our People’s Footsteps”: NPS Employee Trains Future Generation of Stewards at Kalaupapa National Historical Park

NPS Photo

Molokai Light served as a gray area, a place where exiled Hansen’s disease patients could steal away for a chance of seeing the outside world. Now, thanks to Kaiama’s leadership and the hard work of his crew, the restored buildings can proudly serve the needs of Kalaupapa’s remaining residents. We sat down with Kaiama to learn about the project and its significance.

-

Kaiama on preserving the legacy of Kalaupapa

Kaiama shares why working at Kalaupapa NHP and preserving its historic buildings is important to him.

Hawaiians referred to the disease as ma‘i ho‘oka‘awale, “the separating sickness.” People thought to be infected were banished to live in isolation on the island. From 1866-1969, the Kingdom of Hawai‘i, and later the territory and state of Hawai‘i, exiled approximately 8,000 people here. These individuals were separated from their families and children under the rationale that this would halt the spread of the disease. Patients were stigmatized by the outside world. Ideas about leprosy became intertwined with notions of racial difference that characterized Hawaiians as dirty, backwards and uncivilized, justifying the United State’s efforts to exert political and economic control over the islands.1 In spite of all this, the resident of Kalaupapa transformed their place of exile into a home and community. Residents fought for dignified treatment of people affected by Hansen’s Disease and asserted their right to maintain control over their own lives.

NPS Photo/National Historic Landmarks Program

Molokai Light was a place that existed “outside” the settlement, and thus outside its restricting rules. No one under the age of sixteen was allowed in the settlement. Family members have shared stories with the park about patients driving out to the lighthouse to see children playing, often passing candy through the fence to them.2 This brief contact filled a void created by quarantine policies, which mandated that any children born to patients be taken away at birth. In more ways than one, Molokai Light was a beacon of hope for many patients.

-

Kaiama on historic preservation

Kaiama shares the craft involved in historic preservation.

Left image

Windowsill in need of repair

Credit: NPS photo

Right image

Final restored windowsill

Credit: NPS photo

-

Kaiama on training his crew

Kaiama shares why he takes the time to pass on his craftsmanship to his younger crew members.

NPS Photo

-

Kaiama on inspiring the next generation of stewards

Kaiama talks about the importance of carrying on the legacy of Kalaupapa into the future.

NPS Photo

- David Shepherd

- Eddie English

- Edison Makekau

- Joseph Kaheʻe V

- Joseph Mollena

- Lansen Kaupu

- LeAnna Lang

- Makana Kaholoa’a

- Matt Padgett

- Paʻone Lee-Namakaeha

- Pu'uhonua Pescaia

- Rob Pascua-Pelekai

- Cheyne Naeole

- Ka’ohulani

Citations

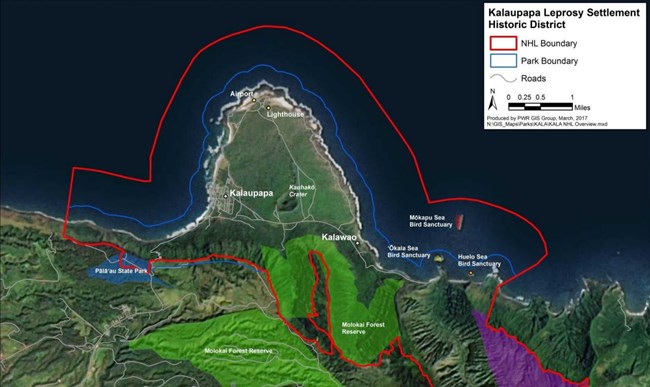

1 National Historic Landmark Nomination, updated documentation, January 12, 2021.2 Personal communication between Kalaupapa NHP Cultural Resource Program Manager and Ka'ohulani McGuire, family member of Kalaupapa resident. Shared with author via email April 2023.