Last updated: July 7, 2021

Article

"The Most Important Political Change We Have Known" JAG, Slavery, and Justice in the Civil War Era (part 1)

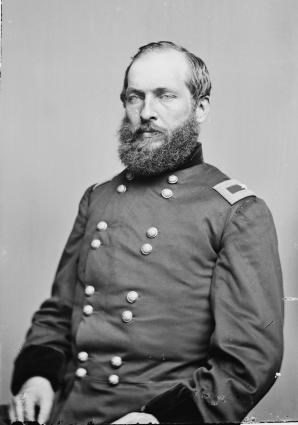

Original photo by Mathew Brady

In the last year-and-a-half, a new book, Destiny of the Republic, has been published regarding the incident for which this late nineteenth century president is remembered by most Americans, if he is remembered at all: his assassination. But there is much more to James A. Garfield than the manner of his death. Born into poverty with no material advantages, he harnessed his broad intellect and natural curiosity to become a well-educated and cultured individual. He was a preacher, a teacher, a college president, an Ohio state senator, a Civil War general, a member of the United States House of Representatives for seventeen years, and the twentieth President of the United States.

The majority of James A. Garfield’s political career was spent in the House of Representatives. Over the course of seventeen years, from 1863-1880, he grew in influence and responsibility. Congressman Garfield had decided views on the economic issues of his day, was a proponent of scientific investigation, and supported a national bureau of education. He also supported the civil and political rights of African-Americans even as those rights were being curtailed in the South. Still, though his public statements about blacks have the ring of a genuine humanitarian concern, it is also true that he had political objectives that coincided with the sincere support for the civil and political rights of blacks that he expressed right into his presidency. At the same time, it is also clear that he shared attitudes about race that were common in his day.

James Garfield’s earliest comments regarding African-Americans, and specifically slavery, appear in his diaries of the 1850s when he was a young man in his twenties. It is important to note that at this time his views on slavery and politics were thoroughly influenced by his religious affiliation, the Disciples of Christ. Many Disciples contended that no one who was concerned with politics could be a Christian, a conviction Garfield adopted when he became a member of the sect at age nineteen in 1850. On numerous occasions he spoke of his disdain for politics as contrary to being a Christian. For example, he wrote on Thursday, September 5, 1850, “I have engaged to support the following proposition, viz., Christians have no right to participate in human governments!” And after hearing a sermon about slavery in October that year, he read essays on the relationship of slavery to Christian thought. He concluded that, “the simple relation of master and slave is not unchristian.”

Ohio Historical Society

Within a few short years, James Garfield’s views on politics and slavery had changed. Study, experience and intellectual maturity “gradually and somewhat painfully shook [him] loose from some of his smugly-held beliefs.” In 1855, while he was a student at Williams College in Massachusetts, Garfield heard two abolitionist lecturers whose attacks on slavery completely altered his views: “I have been instructed tonight on the political condition of our country, and from this time forward I shall hope to know more about its movements and interests.”

He was now convinced that slavery must not be allowed to spread into the new territories acquired after the Mexican War. In his youthful enthusiasm he confided to his diary that, “At such hours as this, I feel like throwing the whole current of my life into the work of opposing this giant evil. I don’t know but the religion of Christ demands such action.” He also wrote, “I am sometimes led to think that our people are not yet fit for Liberty, nor worthy of it, but ‘Let come what may come.’ Slavery has had its day, or at any rate is fast having it.” What a reversal in his view of politics and Christianity.

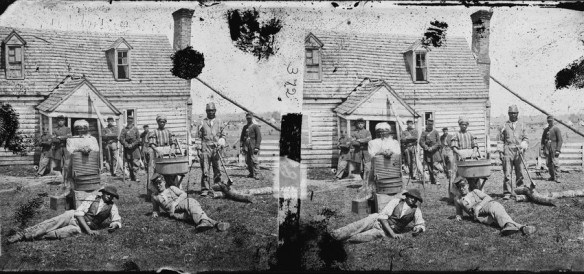

Library of Congress

CIVIL WAR YEARS

During the Civil War, Garfield’s military service convinced him that the institution of slavery was politically and morally bankrupt. Particularly disturbing to him was the bigotry in the Union army that he witnessed first-hand. Writing from Pittsburg, Tennessee to his friend J. Harry Rhodes, in May 1862, he expressed his disgust with army politics and the “conspiracy among the leading officers, especially those of the regular army to taboo the whole question of anti-slavery and throw as much discredit upon it as upon treason. The purpose is seen clearly both in their words and actions. I find myself coming nearer and nearer to downright abolitionism.”

The passage of the first Confiscation Act by Congress in 1861 permitted the Union Army to take fleeing slaves under its protection. However, many Union generals, particularly those who were Democrats, refused to honor this provision, which angered James Garfield. In 1862, he pointedly rebuked what he termed “the haughty tyranny of proslavery officers.” He wrote, “Not long ago my commanding general sent me an order to have my camp searched for a fugitive slave. I sent back word that if generals wished to disobey an express law of Congress, which is also an order from the War Department, they must do it themselves for no soldier or officer under my command should take part in such disobedience…”

Garfield’s humanity in regard to a slave he encountered in the field is eloquently recalled in The Garfield Orbit, by Margaret Leech and Harry Brown. Shortly after the battle of Middle Creek, Kentucky, in early 1862, “a Negro boy was brought to Colonel Garfield – an odd figure, dressed in Confederate uniform and fully armed and equipped. The servant of a Virginia colonel, Jim Rollins had slipped away near the close of the fight and come to the Union commander to give himself up. Garfield was touched by his trust. His thinking was changing… He was coming to believe that the war to save the Union would inevitably carry nationwide emancipation in its train. It added personal warmth to Garfield’s intellectual conclusion that he stood to this Negro boy as the representative of protection and freedom.”

Though Garfield was troubled by how Union officers treated African-Americans, he was equally aware of the dilemma of what to do with Negro camp followers, especially women and children. The men could be employed as Teamsters or drilled to become soldiers. But with the surrounding country being, in Garfield’s words, “devastated and destitute,” he was “totally unable to see how its people and especially the Negroes will escape actual starvation. Thousands have been abandoned by their masters, who… now cruelly turn them out to perish or become a burden which this army cannot safely assume. We should be obliged to duplicate our rations in less than two months if we took them up to feed and protect. It is one of the saddest pictures I ever witnessed… I wish the government would try some plan of alleviation.”

It is clear that James Garfield responded with compassion to the plight of the enslaved people. The political angling that surrounded them, the circumstances that called into question their survival and his inability to render them aid frustrated him.

In uniform and in Congress, Garfield supported enlisting blacks to the Union Army. He did not give great weight to the fear that such enlistees could lead to slave insurrections. Such a result might indeed lead to bloodshed, “but it is not in my heart to lay a feather’s weight in the way of our Black Americans if they choose to strike…” If the slaves rebelled, that would be all the better in undermining the Confederacy.

In October 1863, Congressman-elect Garfield accompanied Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase to a rally in Baltimore, which called for the unconditional abolition of slavery in Maryland. In a letter to his wife Lucretia, he described finding “15,000 to 20,000 people assembled on Monument Square and the speakers – many of them lifelong slaveholders – made the square bold issue” for ending the peculiar institution in the Old Line state.”He continued, “I was never more delighted and astonished, and when I spoke to them the same words I would address to our people …and hearing their long applause, I felt as if the political millennium had come.”

Click here for part 2!

Written by Alan Gephardt, Park Ranger, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, February 2013 for the Garfield Observer.