Last updated: October 30, 2020

Article

“The Most Important Political Change We Have Known”: James A. Garfield, Slavery, and Justice in the Civil War Era, Part II

Library of Congress

CONGRESSIONAL CAREER

In Congress, James Garfield was confronted by the war and the reconstruction of the South that followed. His goals for the freedmen were very much in sync with the Radical Republican program, especially the passage of the constitutional amendments designed to elevate the status of blacks in American society and under law. He supported the extension of the Freedman’s Bureau, the Civil Rights acts passed in the late 1860s, and with initial misgivings, the 1871 Ku Klux Klan Act. In time, he became disillusioned with radicalism, writing to his friend Burke Hinsdale, “I am trying to do two things, viz. be a radical and not a fool – which… is a matter of no small difficulty.”

Even before the Civil War ended, Garfield could be counted among those who favored the confiscation of rebel property in order to secure a Northern victory. He believed that the South had to be “beaten to its knees,” that both slavery and landed estates had to be abolished. “It is well known that the power of slavery rests in the large plantations… and that the bulk of all the real estate is in the hands of the slave-owners who have plotted this great conspiracy… let these men go back to their lands and they will again control the South…” If the slave-holders continued to have power, they would use that power to the detriment of the freed people, and that would call into question all the blood and treasure that had been expended during the war.

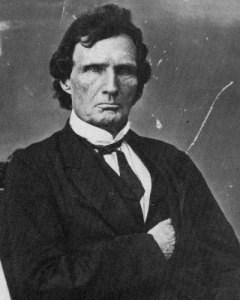

Yet, for all his desire to see slavery ended, he did not want to see African-Americans given “special treatment.” Garfield could not agree with Pennsylvania Congressman Thaddeus Stevens, who wanted to equalize the pay of white and black soldiers. Apparently he thought Stevens’ proposal was a ploy to win political points at home. Though he praised black troops for their devotion and service to the Union, Garfield would not “pat the black man on the back merely because he is black,” and he would not attempt to make “political capital by showing an excessive zeal for the black man.”

Congressman Garfield would not “condescend” to African-Americans. Yet as a much younger man, having attended a lecture on slavery, he observed, “The Darkey had some funny remarks, and witty too.” Was this a condescending, consciously racist remark? Or was he paying “the Darkey” a genuine compliment?

Racial prejudice certainly seems to have been a factor in Garfield’s attitude, when in July 1865, he wrote to his friend David Swaim, “It goes against the grain of my feelings to favor Negro suffrage, for I never could fall in love with the creatures…” It was a private comment – condescending perhaps – that by today’s standards seems to be an ugly remark. Still, whether or not to grant freedmen the suffrage – the right to vote, and under what circumstances – was an enduring and controversial issue during Reconstruction.

If Garfield’s discomfort with the idea of unrestricted black suffrage was based in the race prejudice of his day, it seems likely that his own experience influenced his thoughts just as much. His background was one without advantages, but he acquired education and had abiding interests in history, religion, philosophy, literature, science and the theatre. He grew knowledgeable about the world around him, and felt informed about how it worked and what its needs were. In his eyes, he was fit to exercise his voice and vote in public affairs. Not so every recently freed slave.

icivics.org

Whatever may have been his private reservations, James Garfield was consistent in his public support for African-American suffrage. He condemned the idea that race should determine the right to vote. “Let us not commit ourselves to the senseless and absurd dogma that the color of the skin shall be the basis of suffrage…” he said in a speech at Ravenna, Ohio on July 4, 1865.

In the same speech Garfield spoke of the common cause of the black and white soldier: “In the extremity of our distress,” he said, “we called upon the black man to help us save the Republic; and amid the very thunders of battle, we made a covenant with him, sealed both with his blood and with ours… that, when the nation was redeemed, he should be free, and share with us its glories and its blessings”. And he warned, “[God]… will appear in judgment against us if we do not fulfill that covenant. Have we done it? Have we given freedom to the black man? What is freedom? …Is it the bare privilege of not being chained – of not being bought and sold, branded and scourged? If this is all, then freedom is a bitter mockery…” In expressing these thoughts, Garfield was referring to the mistreatment of blacks in the South, and the racial prejudice they experienced even with emancipation.

Garfield’s support for black suffrage was tied to goals that combined a sincere concern for the welfare of African-Americans with his nationalist point of view incorporating the economic unity of the country and a desire to broaden the appeal of the Republican Party in the South. Without black suffrage, these goals could not be achieved. Like many Republicans, Garfield saw voting was an economic right, as much as a political one. Without the vote, Garfield feared that the freed Negroes would be unable to control their own destinies. They would be left “to the tender mercies of those pardoned rebels who have been so reluctantly compelled to take their feet from his neck and their hands from his throat.” If blacks could not vote, they would “have no voice in determining the conditions under which they are to live and labor…” Under these circumstances, “what hope have they of the future?”

www.learnnc.com

The mix of idealism and political pragmatism embodied in this idea took concrete form in the passage of the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments to the U.S. Constitution. These amendments abolished slavery, conferred citizenship to the freed people, and guaranteed a right to vote for adult Negro males. Subsequent legislation passed in the early 1870s was designed to reinforce those amendments.

During the debate over passage of the 14th Amendment, the necessity of abolishing the three-fifths clause in the Constitution was obvious. While slavery was constitutional, that clause had worked to the advantage of the Southerners in Congress. It counted as three-fifths of a person every enslaved individual, artificially inflating Southern influence in the House of Representatives. By abolishing the three-fifths clause, the influence of the landed whites who had brought on the rebellion was reduced. By conferring citizenship on blacks, their influence was increased. Of the necessity of removing the three-fifths clause, Garfield said, “If the Negro be denied the franchise and the size of the House of Representatives remain as now we shall have fifteen additional members of Congress from the states lately in rebellion… This… will place … the destiny of 412,000 black men in the hands of 20,000 white men. Such an unjust and unequal distribution of power would breed perpetual mischief…”

Throughout the 1870s white Southern racists constantly attacked African-Americans and their Radical supporters, politically, physically, and psychologically. Violence in Louisiana and Mississippi in the mid-1870s was particularly galling, but these events only seemed to encourage Northerners to withdraw from the racial and political problems of the South. Supreme Court decisions nullified civil rights protections and permitted restrictions on the right to vote. James Garfield’s response was to plead for additional civil rights legislation. “God taught us early that in this fight the fate of our own race was indissolubly linked with that of the black man. Justice to them has always been safety to us.” To a friend he wrote in January 1875: “I have for some time had the impression that there is a general apathy among the people concerning the war and the Negro. The public seems to have tired of the subject and all appeals to do justice to the Negro…”

The battle over civil rights protections for blacks was a subtext for political control between Democrats and Republicans. In a highly partisan speech, “The Democratic Party and Government,” Garfield lamented, “that a people, accustomed to [the] domination of slavery, reenacted in almost all of the Southern states… laws limiting and restricting the liberty of the colored man – vagrant laws and peonage laws, whereby Negroes were sold at auction for payment of a paltry tax or fine, and held in a slavery as real as the slavery of other days.” Garfield thought that the “experiment” of allowing Southern whites to have control over the political culture was “a failure.” He condemned “those dreadful scenes enacted by the Ku Klux organization,” calling them “shocking barbarities,” and “sufficient proof …of that great conspiracy against the freedom of the colored race.” He was witnessing the beginning of what historian Douglas Blackmon has chronicled in his book, Slavery by Another Name – the “re-enslavement” of African-Americans by means of forced labor for “crimes” committed. Indeed, as Garfield feared, the freedom won by war was lost in peace.

Written by Alan Gephardt, Park Ranger, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, February 2013 for the Garfield Observer.