Part of a series of articles titled Civil Rights and Public Education .

Article

(H)our History Lesson: South Carolina’s Plan to Oppose De-segregation, School Equalization

This lesson plan was adapted by Katie McCarthy from the full-length Teaching with Historic Places lesson plan “Separate But Equal? South Carolina’s Fight Over School Segregation.”

Grade Level Adapted For:

This lesson is intended for middle school learners but can easily be adapted for use by learners of all ages.

Lesson Objectives:

Students will be able to....

-

Explain how the policy of “separate but equal” affected education in the middle of the twentieth century.

-

Describe the effects of Briggs v. Elliot on the construction of school buildings in South Carolina and on racial segregation in the United States.

-

Explain some of the ways that individuals and institutions worked to maintain racial segregation in the United States.

-

Determine the central ideas or information of a secondary source.

-

Cite specific evidence to support analysis of a secondary source.

Inquiry Question:

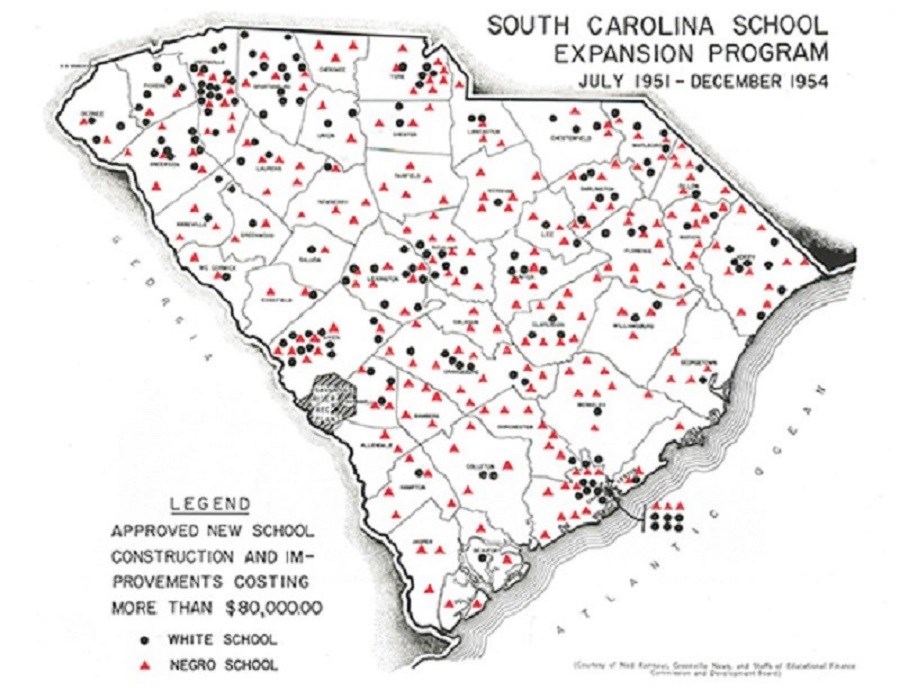

What does this map show? What evidence do you have to support your claim? What do you find most interesting about this map?

Reading:

Background

After slavery was abolished and Reconstruction ended, Southern states began to re-segregate society on the basis of race. In 1896, the Supreme Court ruled in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson that segregation was constitutional, as long as the separate facilities were equal. Following this decision, Southern states quickly segregated all public spaces. Under segregation, African American children never received a "separate but equal" education. Black schools were small and dilapidated. Generally, Black teachers were not as well-educated as white teachers. Programs such as the Rosenwald Fund, Jeanes Teachers, and the General Education Fund gave outside help to Southern schools. However, school boards continued to ignore education for Black students.1

A survey of South Carolina's schools in the late 1940s showed that the state invested approximately $221 per white student. The school plans for African American students showed an investment of $45 per pupil. The Army rejected one-third of South Carolina's draftees in World War II due to illiteracy.2

Content:

African American parents in South Carolina wanted their children to have the same quality of services and schools as white children received. In Clarendon County, a rural county in South Carolina, Reverend Joseph A. DeLaine led the parents' efforts to make this happen. DeLaine was a local pastor and teacher at Liberty Hill Elementary School. He worked with local parents and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). In 1947, DeLaine and the parents group sued Clarendon County School District #22 for a bus for Black students. The court dismissed the case based on a technicality, but the parents did not give up.3

DeLaine and the local parents decided to sue again. This time they sued in a federal court, not a state court. The lawsuit they filed is called Briggs vs. Elliott. Briggs was the last name of several of the African American children named in the lawsuit. Elliott was the last name of the chairman of the Clarendon County School Board #22 Board of Trustees. The lawsuit listed the differences between the white Summerton Graded School and the Black Scott's Branch School. Scott's Branch School had old books, outdoor toilets, wells for drawing water, and stoves for heating. Summerton Graded had smaller class sizes, indoor plumbing, and new textbooks. This case was heard by the U.S. District Court in Charleston, South Carolina. The District Court had three judges. One of the judges was Judge J. Waites Waring. Judge Waring, a white man, supported the civil rights movement. He told the NAACP to sue for school desegregation instead of for "separate but equal" schools. Because of this, South Carolina's Briggs v. Elliot became one of the first desegregation cases in the United States.4

South Carolina's new governor, James Byrnes, responded to the lawsuit with a statewide school construction program. The purpose of the program was to "equalize" black and white schools. This plan was in place by the time Briggs v. Elliott went to trial in late May 1951. During the trial, South Carolina's defense argued that it was trying to provide "separate but equal" schools.5 The U.S. District Court ruled in favor of the Clarendon County school district. The Court stated that South Carolina should be allowed time to equalize its schools. South Carolina was to give a progress report in six months. The new schools were called "equalization schools" because the state built them to comply with the "separate but equal" policy.6

The State Educational Finance Commission (EFC) was in charge of the school building and improving program. The commission purchased new school buses to bring both Black and white students to school. The program designed modern buildings for Black students with the same features that white schools usually had, like running water and electricity. School districts closed old one- or two-teacher schools and built larger schools with more classrooms. South Carolina created its first sales tax to fund the program.

Not all school districts wanted to participate in the program. Many districts wanted to take the funds from the state and only improve their white schools. Charleston County school officials did not want to build a new black high school to replace one that had closed. Some local districts refused to apply for state funds at all if it meant equalizing their schools. A few black leaders also opposed the new schools, because they wanted desegregation instead of equalization.7

The EFC granted most of its equalization money by 1955. South Carolina built over 700 new schools and spent over $214 million. A newspaper article described the equalization schools as "clean-cut functional buildings, making little or no distinction in design between white and colored schools."8 New classrooms had nine-foot ceilings and "window-walls." Rows of windows allowed a plenty of light to enter the classroom. Classrooms had bookshelves, windows, sinks, closets, and chalkboards. Some even had their own toilet. The school had a library, nurse's room, cafeteria, kitchen, and indoor bathrooms. Central boilers, not stoves, heated the school.

Even though African American students had new schools, they still lacked books for their libraries and new desks in their classrooms. When the Supreme Court ruled against segregation, South Carolina did not comply. South Carolina maintained its fully segregated system until 1963. Eleven African American students attended Charleston's white schools under a court order that year, but most school districts were still segregated. The federal government stopped this system by 1970. It refused to give money to segregated school districts. Many of the equalization schools closed at that time. African American high schools often became elementary schools in the new system. Most of the equalization schools have been expanded or replaced with new schools.

Discussion Questions:

-

Describe the "separate but equal" policy in your own words. When did it officially become the constitutional policy in the United States? When did it end?

-

Who originally sued the Clarendon County School District #22? What did they want in their petition? How did their goals change in the Briggs v. Elliot lawsuit?

-

What were "equalization schools?" How were they named?

-

Who supported the equalization school program? What were their goals?

-

How were the “equalization schools” different from the older schools for African American children?

-

How did the equalization school program hurt attempts to desegregate public schools in South Carolina?

Activities:

In each of the following activities, learners are encouraged to think analytically and creatively about the history of school segregation. In the first activity, participants research the court cases that were combined to form the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court case. In the seconds, learners imagine what the first day at an equalization school might have felt like. Educators should choose one of the following activities to complete with their participants.

Activity 1: Research Brown v. Board of Education

After the South Carolina District Court’s decision, the NAACP and the Clarendon County parents appealed the ruling to the U.S. Supreme Court. The Supreme Court heard Briggs as well as four other cases from Kansas, Delaware, Virginia, and Washington, D.C. These combined cases formed the landmark case known as Brown v. Board of Education. On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the NAACP, stating that: "in the field of public education, the doctrine of 'separate but equal' has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal." In this activity, participants will study these four cases:

-

Belton v. Gebhart (Bulah v. Gebhart) in Delaware

-

Brown v. Board of Education in Kansas

-

Bolling v. Sharp in Washington, D.C.

-

Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County in Virginia

Divide the class into five groups and assign each group one of the lawsuits. Have each group research and design a poster presentation about the schools that were part of the lawsuits, the laws in those states related to school desegregation, who was suing whom and why in those cases, and what happened in those school districts after the ruling in 1954. Have your students include images and quotes to illustrate the history of those cases on their posters.

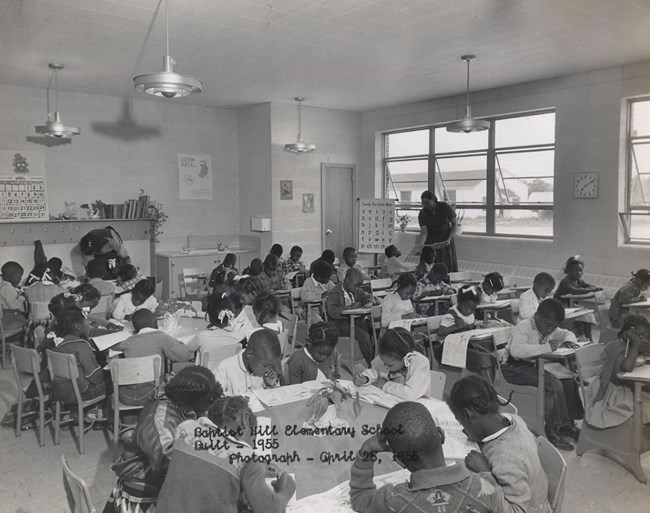

Activity 2: Creative Writing - Imagine Your First Day of School

Have participants spend time looking at the image of the Baptist Hill Elementary School. What do they notice? How might this classroom be “modern?” Does the classroom look similar to the one they learn in? Why or why not? After exploring the picture, have learners write two “first-day” journal entries. The first journal entry should be about their own first day of school experiences. As they do, participants should consider:

-

How did they feel on their first day of school?

-

How was this first day different than other first days of school?

-

What did you think of your new classroom?

The second journal entry should be based on their observation of the picture and their analysis of the reading in this lesson. As they write their journal entry, participants should consider:

-

What emotions might a student in the picture have felt on their first day of school in their new classroom?

-

How might their emotions be affected by the politics surrounding the construction of the school?

-

What might students have thought of their new school?

Wrap-up:

-

How do you think "separate but equal" segregation is at odds with the ideals of the United States?

-

Why do you think the parents of Clarendon County cared enough about their case to bring it all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court?

-

How do you think African American students felt about attending the new equalization schools?

-

Does your own school have a history of segregation or de-segregation?

-

After completing this lesson, what would you like to learn more about? What “puzzle pieces” are missing?

Footnotes:

1 Walter Edgar, South Carolina: A History (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1998).

2 Public Schools of South Carolina: A Report of the South Carolina Education Survey Committee (Nashville, TN: Division of Surveys and Field Services, George Peabody College for Teachers, 1948); Dobrasko.

3Julie Magruder Lochbaum, "The Word Made Flesh: The Desegregation Leadership of the Rev. J.A. Delaine," (PhD diss., University of South Carolina, 1993), 61-62.

4 James Clyburn and Jennifer Revels, Uncommon Courage: The Story of Briggs v. Elliott, South Carolina's Unsung Civil Rights Battle (Columbia, SC: Palmetto Conservation Foundation Press, 2004), 30-33.

5 Clyburn and Revels, 33; Rebekah Dobrasko, "Upholding 'Separate but Equal:' South Carolina's School Equalization Program, 1951-1955" (M.A. thesis, University of South Carolina, 2005), 10-12.

6 Rebekah Dobrasko, "Upholding 'Separate but Equal:' South Carolina's School Equalization Program, 1951-1955 (M.A. thesis, University of South Carolina, 2005).

7 "The Byrnes Tax," Lighthouse and Informer (Columbia, SC), 7 July 1951; Dobrasko, 16-17.

8 Thomas D. Clark, "The Modern South in a Changing America," Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 107, no. 2 (15 April 1963): 129.

Additional Resources:

Equalization Schools Websites

The Equalization School Flickr page features over 1,000 photographs of equalization schools that still exist today. The page has a variety of photographs showing the schools' interiors and exteriors as they look in the 21st century, as well as some historic photographs of schools.

You can learn more about the equalization schools by visiting South Carolina’s Equalization Schools 1951-1960. This website is shares the history of the equalization schools, a list of known equalization schools, and information about preservation efforts. The website is part of the African American Civil Rights Network.

Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian exhibit, "Separate is Not Equal: Brown v. Board of Education", provides context for the five court cases that comprised the Brown decision. The online component of the exhibit showcases photographs of historic schools, detailed information on the history of each case and the individuals involved in each case, and other teacher resources.

National Archives and Records Administration

The National Archives maintains the Documents Related to Brown v. Board of Education website, which provides the full dissent to the first Briggs v. Elliott case written by Judge Waties Waring in 1951 as well as other public documents related to the Brown v. Board cases.

SCIway, South Carolina's Information Highway

SCIway is a clearinghouse for information about South Carolina. SCIway has collected information on African American schools in South Carolina, including links to historic photographs and websites with more information.

National Park Service

The Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site is located at Monroe Elementary School in Topeka, Kansas. Monroe was the segregated school attended by the lead plaintiff's daughter, Linda Brown, when Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka was initially filed in 1951. The park website provides in-depth information on the Brown v. Board case as well as related cases, as well as information for visitors and researchers.

You can learn more about South Carolina’s equalization schools and the associated court cases by visiting this article, published by the National Park Service.

Brown v. Board: Five Communities that Changed America

This Teaching with Historic Places full-length lesson explores the communities whose cases were combined into the historic Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court Case.

Tags

- segregated schools

- segregation

- desegregation

- art and education

- civil rights

- african american history

- education history

- south carolina

- south carolina history

- teaching with historic places

- twhp

- hour history lessons

- educational activity

- desegregation of public education

- late 20th century

- shaping the political landscape

- twhplp

- wwii aah

Last updated: May 9, 2023